In 1935, when Navajo weaver Lousia Alcott wrote to Indian trader Lorenzo Hubbell, Jr. requesting aid due to an illness, she reminded Hubbell of their long-standing, mutually beneficial economic relationship. “Whenever I make a Navaho rug,” wrote Alcott, “I always take it to your store in Tenebito.” Referencing the quality of the rugs that she made, she chided him for the fact that she felt her labor was occasionally undervalued: “Sometimes the price (paid for the rugs) is so low I do not get much out of what I weaved.” Alcott asserted that Hubbell owed her the groceries she needed not simply because she had been underpaid for rugs in the past but also because “I do much for you” and “I help you all the time.” Thus, Alcott’s main point was that a mutually beneficial trade relationship hinged upon both parties’ willingness to “help” each other. She concluded her letter by placing an order for flour, coffee, sugar, and baking powder. Hubbell provided Alcott with the goods she requested because he too recognized the importance in keeping his customers and workers alive and happy.

This correspondence between a Navajo weaver and a Trading Post owner suggests that trade relationships on Indian reservations were complex affairs, not easily reduced to economic formulas and principles. Hubbell purchased Alcott’s rugs because his business depended on the products Navajos had to sell. The fact that Navajos also needed the products traders stocked fortified his position on the reservation, socially as well as economically. Even so, the correspondence also reveals that exchange relationships extended beyond single economic transactions. These exchanges followed modern economic trends, but they did not always conform to straightforward market exchanges that ended once goods and services changed hands. Alcott’s request and remonstration, demonstrate that social accountability had a role in the business of trading.

Except for brief periods in American history, cross-cultural trade relationships between American Indians and non-Indians were plagued by problems of communication, uneven power relations, and a seemingly unyielding demand for the natural resources that Euro or Anglo Americans wanted from indigenous peoples. Most scholars who have documented such encounters tend to focus on trade between Indians and whites in the early contact or colonial era. Yet, trade between American Indians and non-Indians continued well into the twentieth century. The escalation of industrialization, the growth of vast transportation systems, and the rise of a consumption-oriented American public influenced trade relationships between Navajos and non-Navajos. Exchanges at trading posts reflected more than immediate economic interests or cultural expectations; both the national demand for Navajo-made products and the popular representation of Navajo producers as “primitive” artists played a part in this apparently localized trade. We can see these factors in action when we examine the operation of Navajo trading posts.

So, what form did exchanges between Navajos and traders assume as a result of the melding of broad market trends and local concerns? How did pre-conceived notions, cultural mores, and power relationships mediate and affect connections between Navajos and traders from the 1890s through the 1930s? Trading posts were important because that’s where Navajos learned of American consumer demand for the products that they made and because traders shipped the majority of Navajo-made goods from these trading posts to consumers across the nation. And, it was at trading posts that a large majority of Navajos had their first exposure to a consumption-oriented marketplace. Navajos used trading posts to enter the modern industrial economy.

By the late nineteenth century, the term Indian trader described a non-Indian (usually a Euro-American or Hispanic) who exchanged manufactured goods with American Indians for raw materials or handmade crafts on an Indian reservation. By the early twentieth century some businessmen, like Julius Gans of Santa Fe and Maurice Maisel of Albuquerque, had co-opted the term for their own purposes because it signified not only an occupation but also a mythologized lifestyle. By 1900, the trading post itself had become a key economic center and one symbolic of Indian-white encounters more generally.

The commerce that developed between Navajos and traders on the reservation existed because the Navajo economy had been transformed in two fundamental ways. First, the reservation system regulated the movement of Navajos and strictly limited the hunting practices and trade networks that had antedated 1867. In addition, the inter-tribal raiding, a centuries-old method of acquisition among the once nomadic Navajos, had been outlawed. As a result, Navajos developed new subsistence, agricultural, and survival skills that revolved around trading posts. As Navajos manufactured goods to meet non-Navajos’ demand, they also consumed the staples available at the trading posts such as calico and velvet, canned milk, peaches and tomatoes, and manufactured sewing machines, hammers, and hoes. These actions linked them into a larger economic network. Navajos accrued both credit and debt at trading posts. Some debts were seasonal in nature while others could last for years.

Traders like Lorenzo Hubbell and his sons created continual commerce in an area known for its seasonal business cycles by sponsoring ceremonies, accommodating tourists, trading with Navajos, and selling to external markets. When trade with Navajos slowed in the late summer and early fall, tourists would show up. J.L. Hubbell, for instance, hosted thousands of tourists per year in Ganado and Oraibi, Arizona. When the tourist season ended, Navajos again provided the bulk of the business into the winter months. Curio stores and retailers placed large orders for Navajo made jewelry and blankets in November and December to stock-up for the holiday season. After that, in the lean winter season, traders again relied on Navajos who gathered wood, pine nuts, and other resources to supply posts or to be sold in specialty markets. By early spring traders acquired lambs for trade and Navajo sheep for wool to buy or sell. Cash rarely changed hands between trading partners. Instead, throughout the year, Navajo weavers brought in rugs, jewelry, or raw materials to trade for staple items. Traders accepted pawn, to ensure that Navajos would continue to patronize their stores.

Bartered exchanges reflected varied cultural manipulations on both sides of the counter. For instance, one weaver in particular, Mrs. Glish seemed to understand how to use white gender norms to her advantage. Mrs. Glish wove beautiful rugs but, according to Lippencott, was such a tough barterer that it was difficult “for the men behind the counter…to deal with her.” Bill Lippencott especially had a hard time bargaining with the weaver because she had a tendency to weep. On the other hand, Sallie Lippencott Wagner claimed to have the higher hand and she asserted that she was not fooled by Mrs. Glish’s tears and would not pay an elevated price when the weaver cried. Once the price was agreed upon, weavers conducted additional business with traders by obtaining goods. Traders reciprocated by providing something extra, usually canned tomatoes or peaches, in order to maintain good will. Such strategies were used across Navajo country in trading exchanges. While exchanges tended to benefit traders more than weavers, trading post exchanges show us that the nature of trade, and the meanings associated with it, depended upon a mutual understanding of both contemporary economic practices and cultural mores.

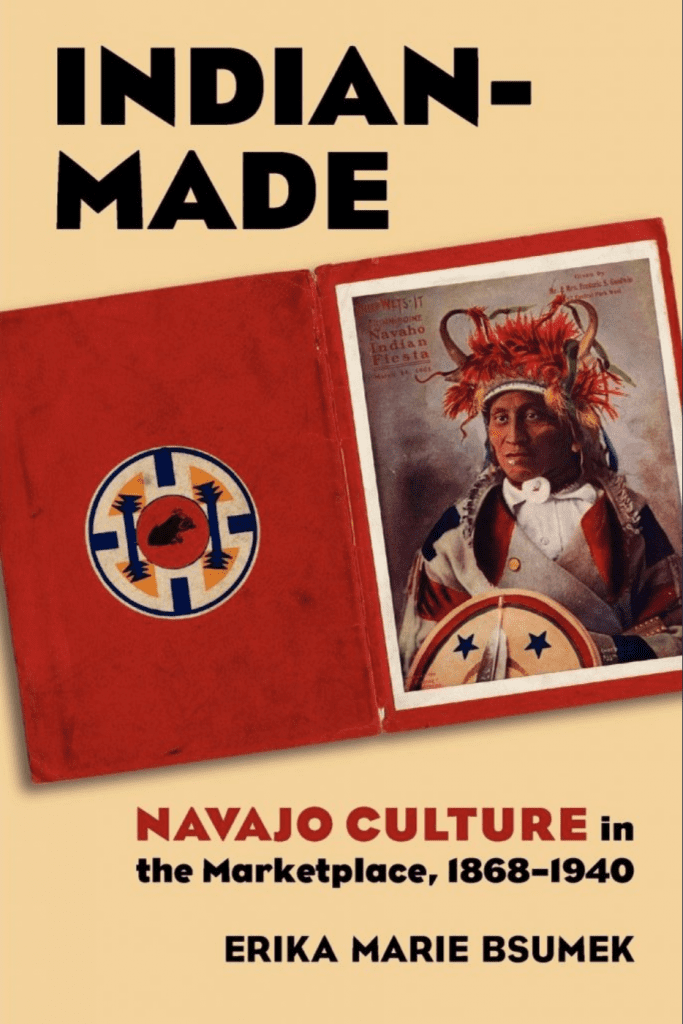

Nancy Bloomberg, Navajo Textiles: The William Randolph Hearst Collection, (1997).

Hearst became enthralled with Navajo rugs after visiting a Fred Harvey exhibit of Navajo goods. Bloomberg illuminates both the history of Navajo weaving and Hearst’s collecting behavior.

Jennifer Denetdale, Reclaiming Dine’ History: The Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita, (2007).

Denetdale, Manuelito’s great-great-great-granddaughter, rewrites Navajo history from the inside out. A groundbreaking work essential for anyone interested in the history of the Navajo.

Stephen Fried, Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West, (2011).

Fried introduces readers to the innovative and entrepreneurial Fred Harvey as he builds a chain of hotels, integrates Native American culture into it, and spawns a vibrant tourist and travel industry in the American West.

Nancy Parezo, Navajo Sandpainting: From Religious Act to Commercial Art, (1991).

Parezo details the origins and evolution of Navajo sandpainting.

Sallie Wagner, Wide Ruins: Memories from a Navajo Trading Post, (1997). Wagner traded on the Navajo reservation for most of her adult life. She offers an insider’s perspective of the trading post system.

Hampton Sides, Blood and Thunder: The Epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West, (2007).

“Blood and Thunders” were a popular genre of dime novels, heavy on adventure, light on facts. In Hampton Side’s chronicle of Kit Carson’s life, the author keeps the action and adventure alive but hews to the facts. A fun and informative read.

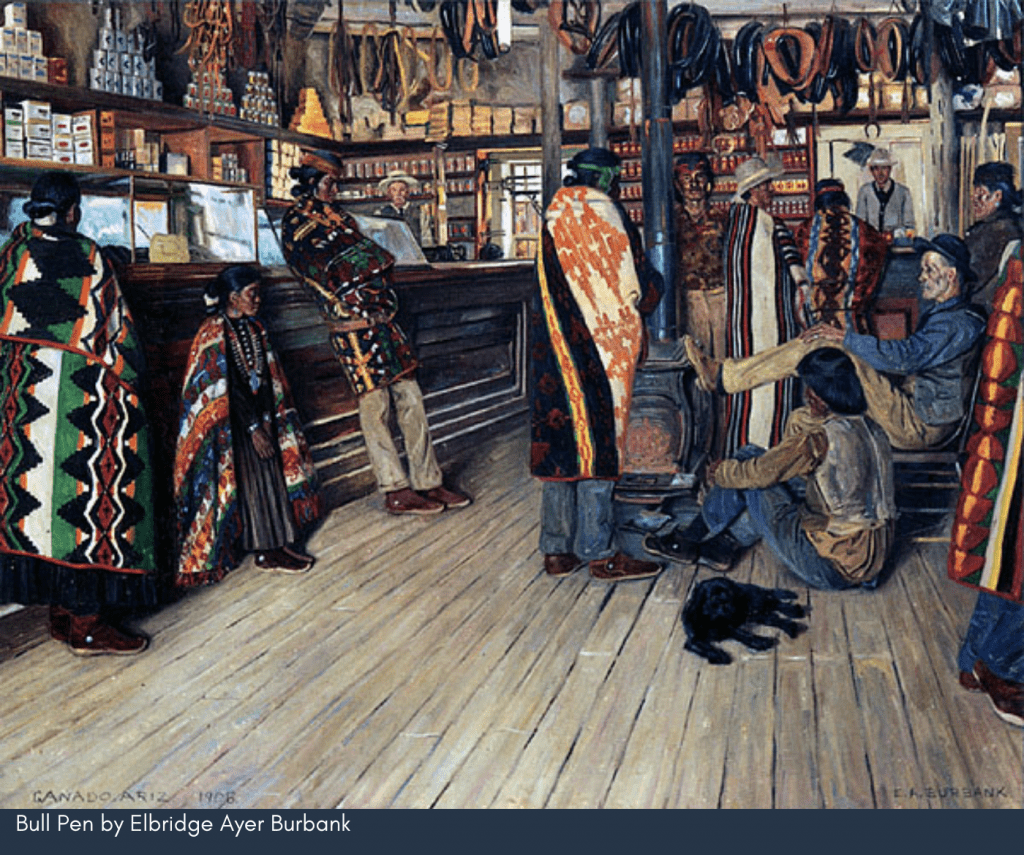

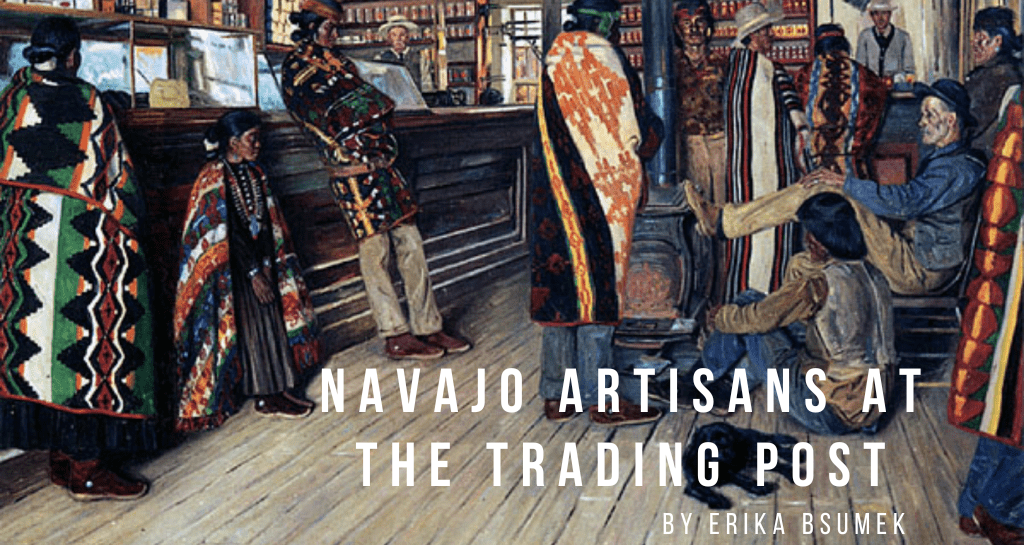

Photo Credits:

Blanket weaver – Navaho (c 1904) from The North American Indian; v.1; Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s ‘The North American Indian’: the Photographic Images, 2001; Bull Pen by Elbridge Ayer Burbank. Burbank painted this “Bull-Pen” view of the Hubbell Trading Post at Ganado showing Navajo people visiting and buying food during the winter of 1908. The white-haired Anglo man behind the counter could be J.L. Hubbell. Charlie [Carlos] Hubbell [J.L.’s brother] could be the man sitting by the stove. The little girl against the counter may be one of Ya-otza-Beg-ay’s [see HUTR 2033] children. The dog lying on the floor in the foreground is “Wa Wa.” Oil on canvas. L 39.9, W 51.3 cm. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, HUTR 3457.