Today we often associate hybrid or genetically modified corn with agricultural monopolies, big business, and capitalism, in the early Cold War some feared that the rise of hybrid corn would sow the seeds of Communism in the United States. Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick’s editorial cartoon, “Alien Corn,” published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on April 28, 1948, shows Henry A. Wallace grinning at a corn plant, whose leaves bear hammers and sickles and whose tassel sports a Soviet star –- the fruits of Communism.

Alien Corn (04-28-1948), by Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick. The cartoon is held at The St. Louis Post-Dispatch Editorial Cartoon Collection. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri.

Wallace was the founder of the Hi-Bred Corn Company (today owned by the Dupont Corporation). He was also vice president to Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of Agriculture (1933-1940), Secretary of Commerce (1945-1946), and 1948 presidential nominee of the Progressive Party. Appearing during the 1948 election season, the cartoon most directly reflects contemporary suspicions about Wallace’s possible Communist sympathies, which were fueled by his endorsement from the U.S. Communist Party, his progressive platform that included universal health care, voting rights for African-Americans, and an end to segregation, and his interest in Eastern religions. Here, the fear of the “alien” seems to have stronger political than environmental implications, yet this title presciently describes the many ways in which these two concerns would become more and more closely intertwined.

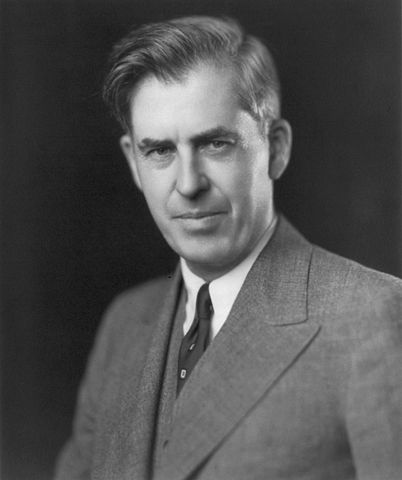

Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick at work. Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection.

The cartoon also seems to reference concerns about the role that Wallace originally envisioned for hybrid seeds in the American agricultural landscape. During his early experiments in western Iowa in the late 1920s, Wallace invented and distributed hybrid corn seeds to farmers across sixteen counties. He imagined that the seeds could provide a means of developing a non-profit, quasi-cooperative agricultural model, that would allow many farmers to contribute a consistent product to a common pool, keeping fifty percent for themselves and donating the other half towards research that would in theory improve the quality of their future crops. Wallace’s model, therefore, for some evoked the ideological spirit of Soviet collectivism. However, in “Alien Corn,” Wallace’s hammer and sickle-laden corn stalk is ironically enclosed by a cement wall and a spiked iron fence, perhaps intended to portray Wallace as a personal profit-seeking hypocrite.

The fence also points towards Pioneer Hi-Bred’s rising profitably and increasing corporatization. In 1949, a year later, it would sell one million units. Much of this expansion had occurred due to the environmental and economic events of the twenty years since Wallace began distribution. During the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, the Department of Agriculture bought and regulated the drought-resistant hybrid seeds in order to stabilize food prices, a program that proved popular and contributed to Wallace’s rising political success. This remarkably rapid growth, combined with the marriage of hybrid seed companies with the chemical companies Dupont and Monsanto (who would provide the pesticides and fertilizers compatible with hybrid seeds), accounts for the major ideological shift in political conceptions of the role of hybrid seeds between the early 1920s and mid-century. Originally envisioned as lynchpins in a cooperative agricultural model, under control of the government, the seeds became essential to the success of a regulated capitalism that would position itself as an antidote to Soviet Communism.

The cartoon also foreshadows an important political moment that occurred about ten years later, as tensions with the Soviet Union escalated. Wallace’s head salesman, Roswell Garst, hosted Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s 1959 visit to Iowa. There, the two powers exchanged ideas for agricultural innovations and the Soviet Union acquired U.S. patented seeds to be planted on Russian soil. Described in a newsreel as one of the “most folksy and jovial days” of an otherwise fraught diplomatic visit, Garst’s and Hi-Bred’s participation signaled the importance of hybrid seeds as geopolitical instruments, through which the United States could assert its technological and ideological power.

“Alien Corn” highlights the ambiguous position of United States agricultural products as both public and private resources in a moment that in many ways represented a turning point in American agriculture. Today, while agricultural industries are intensely corporatized, they also receive state subsidies and the protection of the FBI, which is becoming increasingly invested in patented seeds as geopolitical bargaining chips to be used in diplomatic relations with national powers such as India and China. At the same time, there is mounting public concern over the environmental and health effects of the widespread cultivation and consumption hybrid seeds. The cartoon then prompts us to think about how the environmental conditions inherent to hybrid seeds –including their ability to thrive as monocultures and their dependence on chemical pesticides— affect their local and transnational ideological implications.

You might also like:

Our feature, Nation States and the Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental History, edited by Erika Marie Bsumek, David Kinkela, Mark Atwood Lawrence (Oxford University Press, 2013)

Felipe Cruz reviews Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption & Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States, by John Soluri (2005)

Kody Jackson recommends The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King, by Rich Cohen (2012)

Neel Baumgartner on Big Bend’s “scenic beauty”

Erika Bsumek on Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification project

And watch Blake Scott and Andres Lombana-Bermudez’s short documentaries on the history of tourism in Panama

These recommendations of important works in environmental history