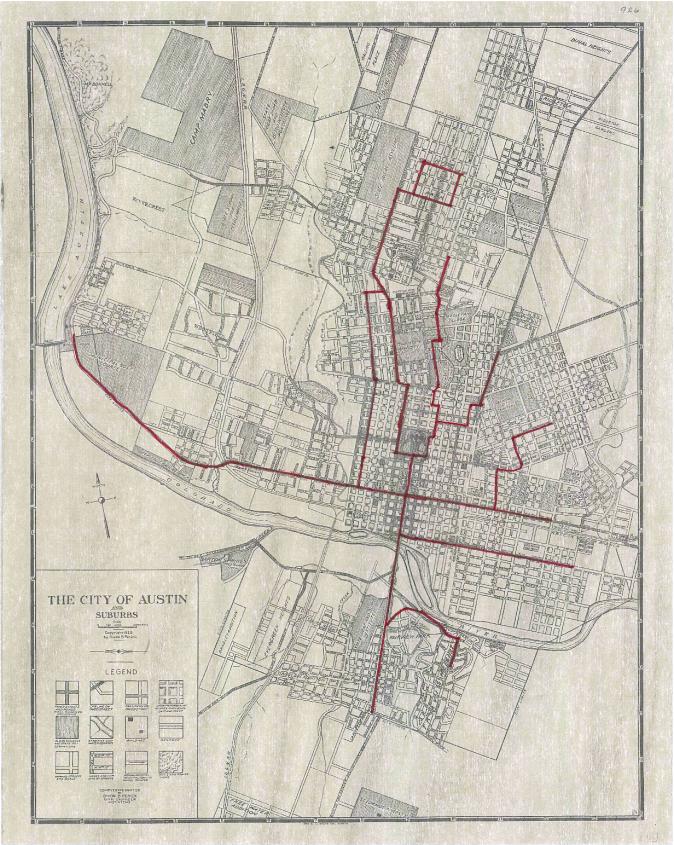

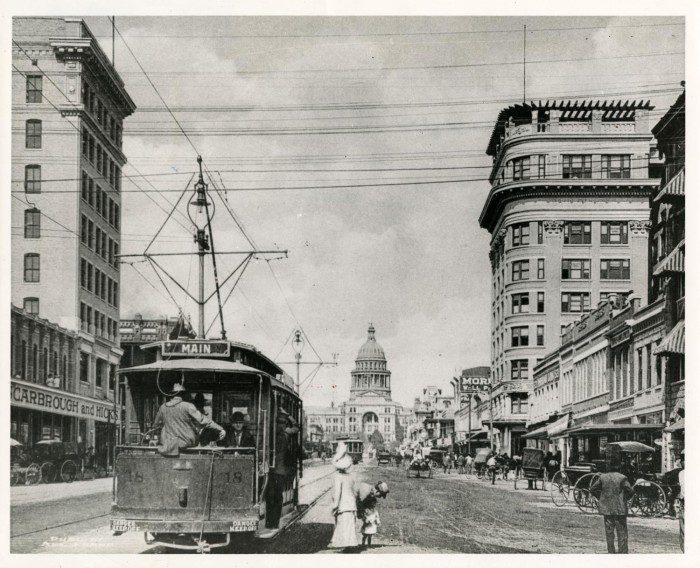

As Austin considers building a new electric light rail system—streetcars, really—it is worth looking back to the city’s first streetcar era. For fifty years, from 1891 until 1940, Austin had an extensive network of electric streetcar lines, running from Hyde Park in the north to Travis Heights in the south, and from Lake Austin in the west to the heart of East Austin. The trolley cars were central to the lives of many Austinites, carrying them between their homes, jobs, and schools, shaping their decisions about where to live and work, and providing a site for racial contact and conflict at the height of the Jim Crow era. Austin was far from unique in any of this. Electric streetcars were one of the defining technologies of cities and towns around the world from the 1890s until at least the 1930s, and a look at Austin’s experience with streetcars will help us to see how global patterns played out in a local setting.

Austin’s first streetcars were propelled by mules, not electricity. They began operating in January 1875 and ran mostly along Congress Avenue from the train stations up to the Capitol. Austin was the railhead in the mid-1870s, the farthest point reached by the railroads, and though it only had about 10,000 residents, it bustled with activity. As the railroads extended further west, however, Austin became something of a backwater, and by the 1880s city leaders were looking for new ways to spark growth and development. They hit on the idea of building a huge dam to supply industrial power, and though the project eventually proved disastrous, it set off a speculative boom in the city in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

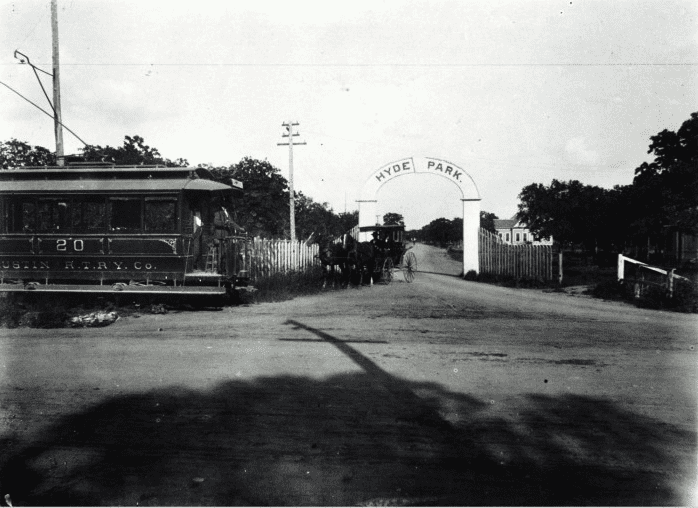

One of those attracted to what Austin seemed to offer was Monroe Shipe, a developer from Kansas. After acquiring a plot of land north of town, which he rather grandly dubbed “Hyde Park,” he set about offering what he said would be the finest home sites in the region. But Hyde Park was too far from the center of town to be attractive to potential buyers; Shipe needed a way to bring it closer. In May 1889 he set out to do just that, securing a franchise from the city for the Austin Rapid Transit Railway Company and setting out to build an electric streetcar line running from downtown to Hyde Park.

Electric streetcars were the hot new technology in 1889. Thomas Edison and others had been trying for several years to devise a practical way to use electricity to drive streetcars, but it was Frank J. Sprague who in 1888 managed to pull together a working system. Working on a short deadline in Richmond, Virginia, Sprague designed and built a streetcar system that was rugged, efficient, and clearly superior to any of its competitors. One of his key steps was to power his cars from overhead wires tapped by the arm of a spring-loaded “trolley,” a name that was soon applied to the cars themselves. Sprague’s new system spread extremely rapidly, and within a few years hundreds of electric streetcar lines were up and running all over the United States. The new technology came along at just the right time for Monroe Shipe, and he jumped on it.

Shipe’s franchise required him to have his line in operation under electrical power by the end of February 1891. He beat the deadline, he later said, by just one hour and forty-four minutes. The line was an immediate hit, no doubt initially in part for its novelty value. Over 2000 Austinites rode Shipe’s streetcars that first day, and the line continued to carry heavy traffic for months to come, many riders taking the loop all the way out to Hyde Park. Like many streetcar operators around the country, Shipe built attractions to draw riders at off-peak hours; though in other cities these often took the form of garish amusement parks (many with names like “Electra Park”), Shipe provided a more sedate pavilion and lake at the north end of his line (near 43rd and Guadalupe), perfectly placed to allow visitors to see how pleasant their lives could be if they bought a home site in Shipe’s development. With its tree-lined streets and carefully planned amenities, Hyde Park was a classic streetcar suburb, of a kind that began to appear all over the United States toward the end of 19th century. Rapid and convenient electric streetcars allowed city-dwellers to live much further from their jobs than had previously been possible, contributing to a shift in housing patterns and a greater separation between home and workplace. Shipe promoted Hyde Park as the “bon ton residence” of Austin, and especially in the early years sought to attract the upper stratum of Austin homebuyers.

The Austin City Railroad Company, the operators of the old mule car line, resented Shipe’s intrusion into the Austin transit business and fought back hard during the early months of Shipe’s operation. Then in May 1891 a fire struck the old company’s barn, destroying many of their cars and killing thirty mules. The owners, described as “a syndicate of Chicago and Boston capitalists,” leaned toward liquidating their remaining property, but decided first to see what they might salvage. According to the Austin Statesman, whose boosterism in those years knew few bounds, once they visited the city, the northern investors were so impressed by Austin’s “brilliant future” that instead of selling out they decided to invest in rebuilding and electrifying their system. By the end of 1891 the two companies had merged into a fully electrified system whose twenty cars ran on fifteen miles of track that reached through most of the city north of the river.

Soon after he had engineered the merger, Shipe withdrew from the streetcar business. He knew the real money lay not in collecting nickel fares, but in using the availability of streetcar service to boost the value of the land he was trying to sell. It was a wise move. After the early 1890s, Austin’s streetcar companies struggled financially; though they experienced occasional periods of profitability, generally after receiving an infusion of outside capital, these were inevitably followed by stagnation, losses, bankruptcy, and reorganization. In 1902 the Austin Rapid Transit Railway Company gave way to the Austin Electric Railway Company, followed in 1911 by the Austin Street Railway Company and in 1921 by Austin Transit.

Austin itself struggled, too. The dam, completed in 1893, never produced enough power to attract industrial customers, and the city was saddled with an enormous debt and little way to pay it off. Then in April 1900 the dam failed in a flood, leaving the streetcar system without power. Mules were pressed into service for several months until the streetcar company could erect its own steam powered generators at 4th and Pressler Street on the west side of town.

Shipe found that the market for high-end house lots in Hyde Park had declined as well, and he began to aim his pitch a little further down market, offering lots on favorable terms of just $2 per month. On one point, however, the pitch remained the same: as Shipe’s advertisements stated in bold letters, “Hyde Park is Strictly for White People.” Racial lines were hardening in the 1890s, and the advent of electric streetcars and streetcar suburbs made it easier to enforce a separation in housing patterns.

The turn of the century also witnessed a wave of Jim Crow laws mandating segregation on public transportation. City councils across the South passed ordinances requiring separate seating on streetcars, with blacks forced to the back. The streetcar companies generally opposed such laws, saying they imposed new costs without providing any new revenues, made it more difficult to respond to shifts in demand, and forced drivers and conductors to enforce policies that were likely to arouse opposition. In many cities, black citizens boycotted the segregated streetcars in favor of informal “hack” lines of wagons and carriages operated by black drivers. The Houston Electric system was hit especially hard; after the city passed a Jim Crow law in November 1903, black ridership plummeted. A few months later, the white streetcar drivers went on strike, further crippling the system. When frustrated whites asked the black hack drivers for a ride, they were politely told that the city ordinance prohibited letting blacks and whites sit together, and that the hack wagons did not have the required separate compartments.

The Houston streetcar boycott fizzled out toward the end of 1904, but others followed. In March 1906, the Austin city council passed an ordinance requiring segregated seating on all streetcars. The law was not set to take effect until June, but blacks began their boycott immediately, and by April the Austin streetcars reportedly carried almost no black riders. Black drivers soon started up mule-drawn hack lines, and local black leaders even talked of acquiring a “large auto passenger bus” to carry black riders. But despite determined efforts, the boycott collapsed in June, and black riders seemingly resigned themselves to taking their places in the back of Austin’s streetcars. Public transportation remained a racial battleground in the South, however, as the story of Rosa Parks and the 1955–56 Montgomery bus boycott makes clear.

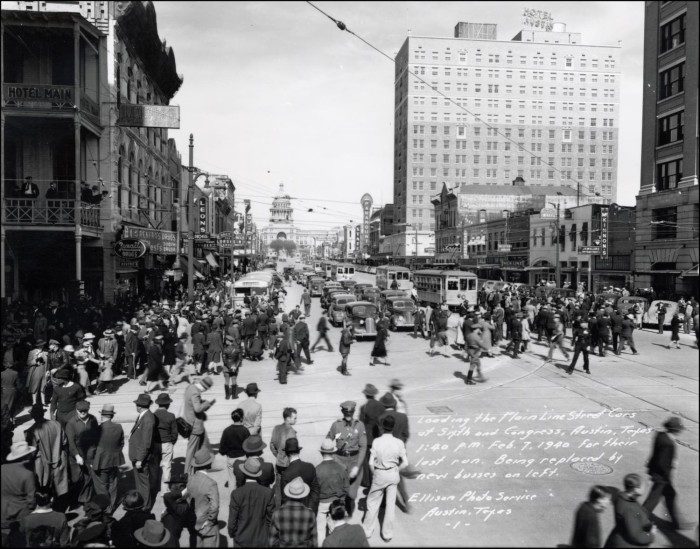

Both Austin and its electric streetcar system continued to grow in the early 20th century. After the new concrete Congress Avenue Bridge was built across the Colorado River in 1910, streetcar lines were extended into South Austin and the new suburban development at Travis Heights. Lines were also extended further into East Austin, until by the mid–1920s the system reached its peak extent, with 23 miles of track to serve a population of about 40,000. By then, however, the streetcars were coming under increasing competition from automobiles, and farebox income was insufficient to keep the streetcar system in good repair. Many cities began to shrink their networks of streetcar lines, and in 1933 San Antonio became the first major city to junk its electric streetcars in favor of buses. Austin followed in 1940. In a ceremony presided over by Mayor Tom Miller, Austin’s electric streetcars made a last nostalgic run along the Main Line up Congress Avenue on 7 Feb. 1940 before giving way to shiny new buses. The remaining rails were pulled up in 1942 during a wartime scrap metal drive.

I first began delving into Austin’s streetcar history while teaching an undergraduate seminar on “Electrification.” I encourage my students to explore the rich local history of electrical technologies and their social impacts, and they have turned up some fascinating stories. In fact, much of what I said above about the 1906 black streetcar boycott was drawn from an excellent paper my student Kevin Stewart wrote a couple of years ago. I have also learned a lot just by talking with Austinites. I recently gave a talk about Austin’s streetcar history at the Neill-Cochran House Museum in West Campus, and struck up a conversation there with Virginia Wallace, a longtime Austin resident. Her stepfather was a streetcar driver, and she described how handsome he looked in his uniform. She also told how, sometime after the ceremonial “last run” in February 1940, he let her ride with him as he drove the last streetcar to the old car barn on Pressler Street to be retired. With that Austin’s streetcar era—or at least its first streetcar era—came to an end.

Check out more of Professor Bruce Hunt’s contributions to Not Even Past:

“City Lights: Austin’s Historic Moonlight Towers”

“The Rise and Fall of the Austin Dam”

“The Atomic Bombs and the End of World War II: Tracking an Elusive Decision”

Photo Credits:

Streetcar along the entrance to the Hyde Park neighborhood of Austin

Citation: [Gated Entrance to Hyde Park], Photograph, 1894; digital image, accessed March 18, 2013), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas.

A 1925 map of Austin with the streetcar lines highlighted (Image courtesy of Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection)

Streetcar on Congress Avenue, 1913

Citation: Congress Avenue with street rail, Photograph, 1913; digital image, accessed March 18, 2013, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas.

Streetcars run along Congress Avenue on their “last run” in Austin, February 7, 1940

Citation: Ellison Photo Service. Street Railroad Downtown, Photograph, February 7, 1940; digital image, accessed March 18, 2013, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas.

Congress Avenue after the streetcar lines were removed, 1943 (Image courtesy of the U.S Government)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.