In the heart of downtown El Paso, an important Texan border town that lies at the base of the Franklin mountains, centuries of history are at your fingertips. Thanks to a 2016 initiative, the El Paso Museum of History has compiled all of its historical records through to the present day into an innovative touch-screen exhibition.

Multiple display options demonstrate the city’s prioritization of community collaboration with this project. As a result, these digital portals into the El Paso past provide a model for making history accessible to the public and for reminding the people of the community that their city’s history belongs to them.

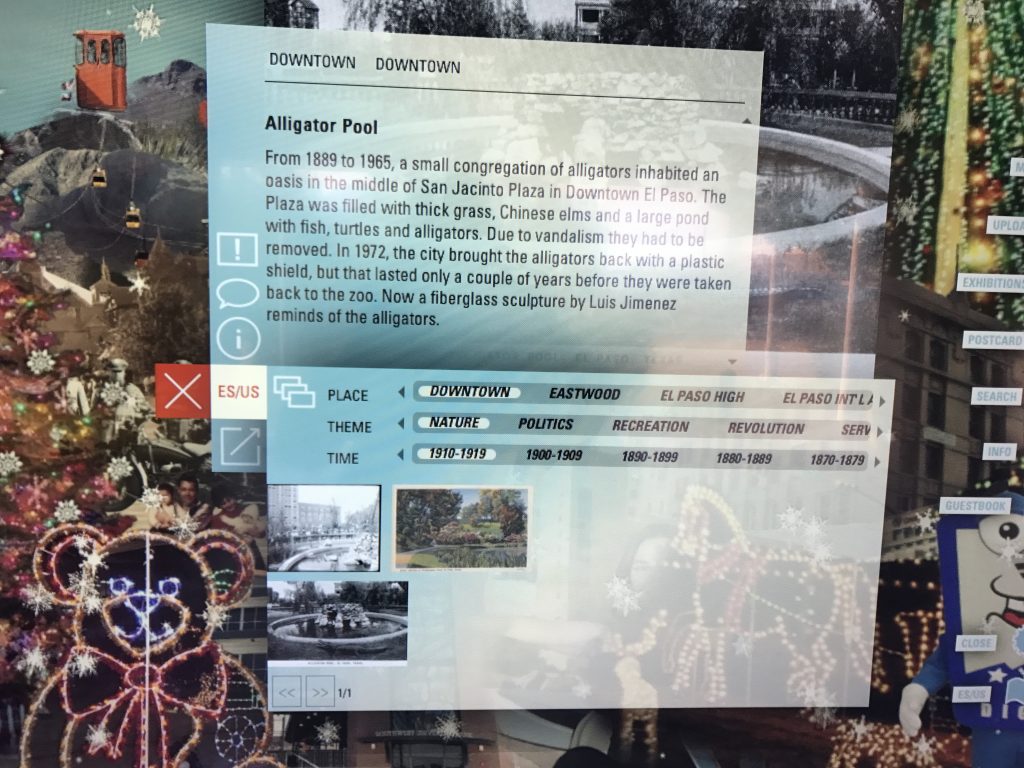

The five panels of this wall-length touchscreen invite museum-goers to explore the history of El Paso on their own terms. Far from a generic desktop screen, these panels portray lively scenes of El Paso, from prominent city corners to quiet neighborhoods. Historical and modern-day photographs infuse the scenes with an authentic local character. Each feature of that screen–whether building, person or other feature–is clickable, providing visitors with the relevant names, dates, locations of the historical context.

By making their own selections, users can browse topics by time period or geographic region of the city. They can also explore preset categories, such as celebration, education, and faith. As they choose any of these filters, the screen readjusts to show related images and links. When the screen moves, a new scene of city life appears, compiling decades of historical research into an interactive research tool. For especially curious visitors, a search option allows for detailed identification of people, places, or events.

With the touch of a finger, students, parents, children, and tourists alike can immerse themselves in five centuries of local history. Since these display boards are fully functional in both English and Spanish, that immersion is bilingual. These interactive history exhibits are inclusive by-design. Prioritizing inclusivity has helped the El Paso Museum of History strengthen a sense of belonging between their institution and the community. Through these easily accessible displays that cater to users’ interests and choices, viewers can feel the ways that the stories preserved by the museum belongs to them and the wider community. To be sure, those stories have always been theirs since the historical records is the story of people’s lives and experiences. However, unlike more traditional exhibitions, this display makes important progress in breaking down the artificial division in the relationship between the contents of the museum and the public.

Two tools in particular help the El Paso Museum of History accomplish that goal. First, the museum encourages people to add to the narratives displayed on screen by sending in their own images of life in El Paso past and present. This option is available through a QR code for photos taken with a phone, or through the museum’s website for other images. In this way, any community member’s childhood memories or grandparents’ life stories can help the city weave a richer cloth of history. Locals can also upload comments to images in the museum’s digital archive to add or correct information. Account creation is not required for these options.

The El Paso Museum of History has established a rare opportunity for the people of the community to play a major role in historical research and preservation. This hands-on experience of history provides an important bridge between the world of archives and academic scholarship and the rich everyday lives of the people about whom scholars have written for centuries.

You May Also Like:

“Stand With Kap:” Athlete Activism at the LBJ Library

The Museum of Sour Milk: History Lessons on Bulgarian Yogurt

History Museums: The Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Columbia

Also by Brittany Erwin on Not Even Past:

The Museo Regional de Oriente in San Miguel, El Salvador

The National Museum of Anthropology in in San Salvador

Review of The Archaeology and History of Colonial Mexico by Enrique Rodríguez Alegría (2016)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.