Digital History is more than just a new, innovative way of using and presenting historical data. It offers an opportunity to change the way historians and archivists understand the holding, preservation, and curation of artifacts. Archivist and artist Lincoln Cushing has been quietly working at the forefront of this information revolution, spending nearly twenty years compiling, digitizing, and organizing political posters from Cuba, China, and the United States. Available through the website Docs Populi and his ongoing work with the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), these posters represent a truly global exploration of art, politics, and identity available at the click of a mouse.

The importance of this new archive is clear in Cushing’s first major project, the unrivaled collection of posters from the Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, or Organización de Solidaridad con los Pueblos de Asia, África y América Latina (OSPAAAL). OSPAAAL was founded in 1966 to help promote anti-imperial and socialist causes in the developing world. The Cuban-based organization helped define an imagery of global revolution through its dynamic, brightly colored posters that it distributed in the pages of Tri-Continental magazine. Traveling to Cuba in the 1980s, Cushing was stunned to find that despite their importance, there was no archive or even definitive list of OSPAAAL posters. He spent years scouring various repositories on the island, in the United States, and Europe compiling a list of every poster produced until 1995.

Yet rather than bringing these posters together in a single repository, Cushing chose to assemble the archive virtually. An early believer in employing technology to preserve and disseminate knowledge, Cushing used digital photography to bring the artifacts together online, free for all to access as the artists originally intended. The 300 posters therefore represent not the digitization of a physical collection but rather the best available artifacts assembled from individual repositories and private collections scattered across the globe. The images are presented in high definition, faithfully preserving the intricate details, coloring, and overall quality of the prints.

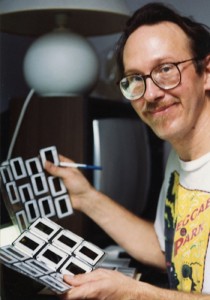

Posters from the Ann Tompkins collection on the Cushing dining room table, some tightly rolled for more than thirty years.

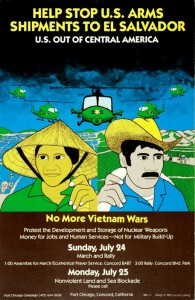

The combination of preservation and accessibility fits perfectly with the idea of activist posters and provided a model for future work. Cushing slowly expanded his digital archive as new opportunities appeared. A member of the Bay Area activist collective, Inkworks Press, his digitization of its work since 1974 has provided an American perspective on leftist politics. Docs Populi added more than 500 images from the Chinese Cultural Revolution after Ann Tompkins (Tang Fandi) worked with Cushing to digitize her entire collection before donating the physical objects to the East Asian Library at the University of California at Berkeley. Finally, Bay Area activist and collector Michael Rossman insisted that Cushing be involved in managing the more than 24,000 images he donated to the Oakland Museum, a collection representing American causes from the 1960s until today. The result is a truly global archive.

Poster for the Port Chicago Campaign (1983) that worked to stop arms shipments to Central America from the Concord Naval Weapons Station in northern California.

Such posters are good candidates for digitization, because artists rarely copyrighted images and indeed desired widespread reproduction, but Cushing has also used technology to manage the ongoing tension between openness and responsible stewardship. With the Rossman collection, the OMCA wanted to maintain the ability for visitors and researchers to engage with the sometimes intricate details of the prints while still preventing anyone from using the high resolution images for their own purposes. The solution: provide a low resolution image with the ability to magnify details for individual exploration. Online visitors have the ability to explore the posters with the same level of detail they would likely have in an archive, all while preventing misuse, preserving the objects themselves, and making them available to audiences unable to visit Oakland.

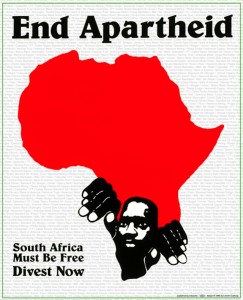

In combining these diverse images in a single digital gateway, Cushing has made it possible to explore the transnational dialogue that occurred between leftist artists. Visitors can browse through the individual collections or search by date, subject, or artist and see the transportation and adoption of ideas that helped create visual vocabularies of revolution and counter-culture. Comparison of material from the OSPAAAL and Rossman archives, for example, illustrate how Cuban artists adopted psychedelic imagery to help sell their ideas abroad. One can even follow the evolution of specific iconography, seeing, for instance, how Americans repackaged Cuban depictions of African revolution (itself borrowed from an Emory Douglas illustration in The Black Panther) to protest Gerald Ford’s intervention in Angola in 1976.

Just as important as finding new audiences and revealing connections is the recovery of information. In contrast to traditional archival practice that only opens public access once the material is fully catalogued, organized, and described, Cushing’s archives have the ability to evolve. The Rossman collection at the OMCA is a perfect example. With more than 24,000 thousand images, fully cataloguing the entire collection will take years. Cushing nonetheless posts the material as soon as possible with minimal descriptions of text, size, and production method that he later supplements with greater detail on the artists and context. This approach opens the collections to the public sooner, but it also provides the opportunity for people knowledgeable on the images to contact the OMCA to provide additional information. This kind of managed crowd-sourcing is, in Cushing’s word, “a very robust way of producing truth.”

The idea of a single digital repository for widely scattered material is especially attractive for decentralized movements and, as a result, Docs Populi is one example of a slowly emerging practice of collecting and centralizing materials on political causes and themes for open access research. While it cannot and should not replace the necessary preservation of documents at the OMCA, the University of California, and elsewhere, it provides a way to bring together scattered information for the purpose of research and education. Cushing’s work provides a model for the ways that new digital platforms can strengthen libraries and archives as they pursue their primary missions of preservation, information collection, and knowledge dissemination.

Catch up on the latest from the New Archive series:

Maria José Afanador-Llach discussed her experience at a Digitilization Workshop in Venice and Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web

Charley Binkow discussed digitalized images from the Folger Shakespeare Library

Charley Binkow explored photographs of California’s Gold Rush

Henry Wiencek found a digital history project that not only preserves the past, but recreates it

Links

Lincoln Cushing on the technical aspects of digitization and online exhibition:

http://www.docspopuli.org/Documentation.html

Texas posters from Michael Rossman’s “All of Us or None” Collection, including a great piece from Austin artist Jim Franklin: http://collections.museumca.org/?q=taxonomy%2Fterm%2F154&keys=texas

Interview with Michael Rossman from “Berkeley in the Sixties”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKFzq9xPwiE

All images courtesy of Lincoln Cushing