This article is part of an occasional series of articles highlighting the extraordinary collection of historical documents in the Briscoe Center for American History at UT Austin.

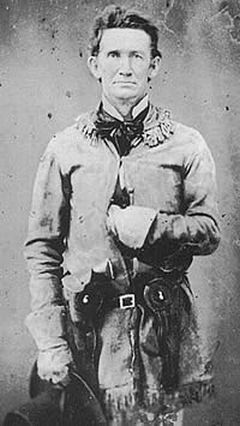

John Salmon “Rip” Ford had a long military career as a soldier of the Texas Republic (1836-46). He was a volunteer in the Mexican War, a Texas Ranger on Texas’s borders, and commander of a Confederate Cavalry Regiment in the Civil War. Ford’s archive at UT Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History, contains records of his activities as a physician and newspaper editor, as well, revealing an uncommon breadth of occupational skills. But the bulk of the archive is occupied by Ford’s voluminous memoirs, which span his life from 1815 to 1892.

Those memoirs detail an informative event in the history of civil-military relations in nineteenth-century Texas. In 1858 Ford refused to follow the orders of a District Judge to arrest eighteen Anglo-Texans accused of murdering reservation Native Americans. This account of what became known as the Garland Affair, after the main culprit, Peter Garland, and Ford’s perspective on the event, provide insight into how Texas Rangers prior to the Civil War perceived themselves in relation to both civil law enforcement and military service.

Ford’s memoir is notable for the clear distinctions he makes between civil authority and military limitations. His argument and actions, as he described them, contradict the popular notion of the Texas Rangers serving as the premier law enforcement order during Texas’s early years. When Judge N. W. Battle ordered the Captain Ford to “forthwith arrest” Garland and his band of settlers in Central Texas for the murder of seven Native Americans, including women and children, the ranger flatly refused. Ford articulates the difference between a “sheriff” and a “military officer,” and further questions the order on “principal” to use his company to “attack a body of American citizens.” He finishes by emphatically stating that the judge had no authority “to command me, as the captain of a company of rangers, to arrest Garland and others.” He also worried that “a civil war might have been the consequence.”

This argument, made by the senior Texas Ranger in the state, revealed the purely military intent of the early ranger forces. Even though the guilt of Garland and the others was never in doubt, and the judge ordered a legal arrest, Ford nevertheless refused “to act except in strict subservience to law.” These Texas Rangers viewed themselves as irregular cavalry, not police forces. It is equally possible that the ranger felt disinclined to move against a fellow Anglo citizen on behalf of a native victim, or that he was hesitant to provoke a possible violent confrontation between his force and the settler militia. Regardless of motive, Ford’s intransigence also reveals that, despite the volatility of Texas’s rough frontier culture, the historical American aversion to military interference in civil matters had matriculated westward. Eventually the captain offered to subordinate his company under the prosecuting leadership of “the civil authorities” to “assist” in the arrest. Garland and his perpetrators, however, were never arrested.

These writings are now partially edited in Stephen Oates’s 1987 book, Rip Ford’s Texas.

More amazing finds at the Briscoe Center:

“The Die is Cast”: Early Texans Face the Comanches

Standard Oil writes a “history” of the old south

Stephen F. Austin visits a New Orleans bookstore

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.