European monasteries were segregated by sex – for men or women only – and the inhabitants were expected to be celibate. In South Asia, where many different religious traditions grew up side by side in the same terrain since the earliest times, monasticism neither insisted on absolute celibacy for men, nor did it exclude women. Many monastic men moved from site to site collecting food and exchanging information. Those who were not ordained as monks but were simply followers or tenants on lands that belonged to a monastery, took herds out on seasonal cycles, traded in goods, and transported goods on behalf of their monastic teachers. Women held these monastic centers together and were central to their everyday lives. They cultivated the land, provided the food and maintenance services, and often, their sons or brothers joined the order or served it in some military or diplomatic task. The functions these little monastic communities carried out make it possible to call them “governments.”

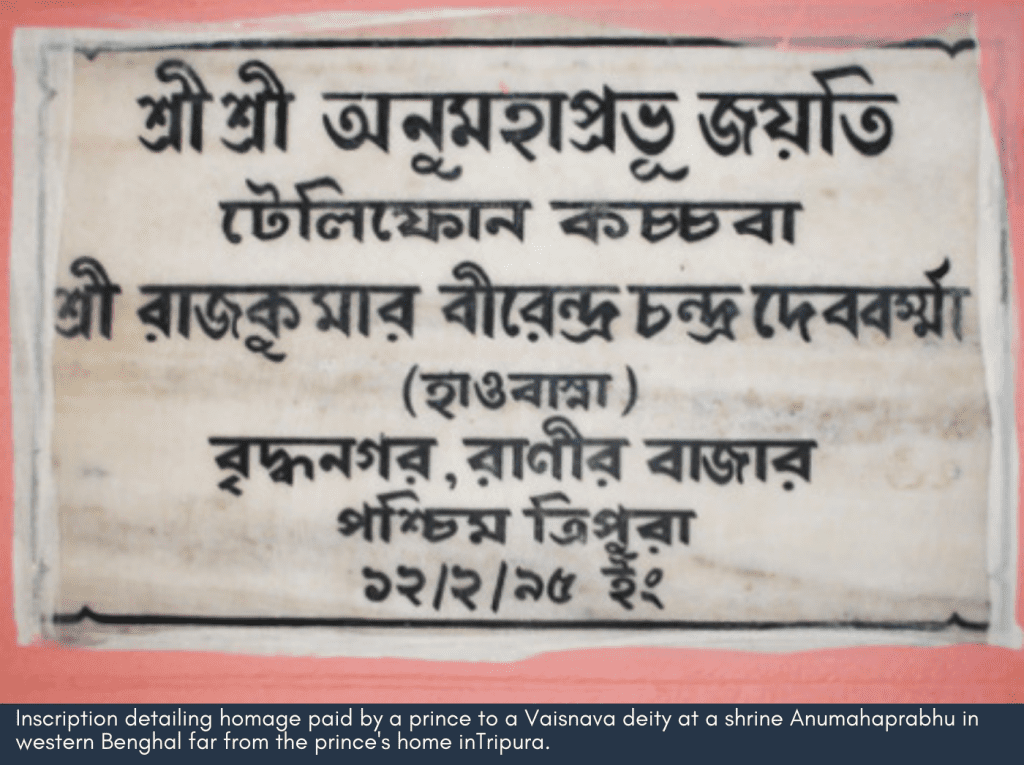

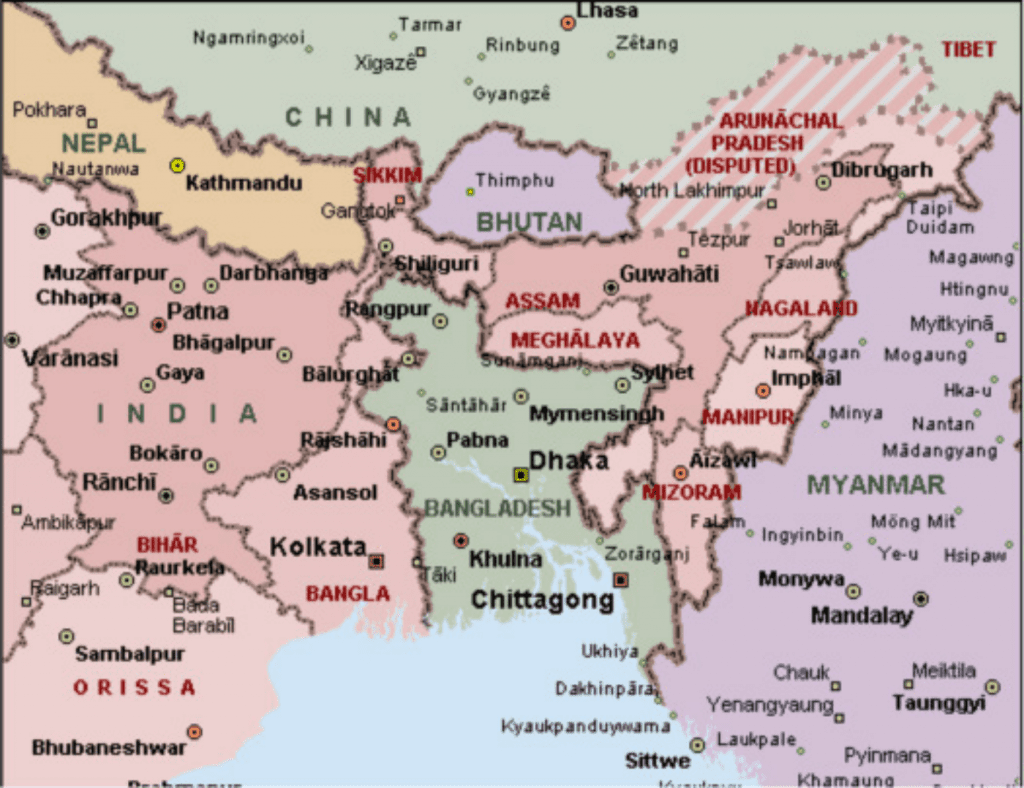

These monastic governments were connected to each other across vast territorial expanses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – before the borders of the modern state of independent India, Pakistan, Bangladesh were carved out. From the mountains of Nepal to the Manipuri Valley to West Bengal, monasteries of diverse religions – Buddhists, Saiva and Vaisnava Hindus, Sufi Muslims, Bonpo Tantriks – shared many political, economic, military, and gender practices. Communities formed around a central leader, who was considered both a teacher and a “friend.” Initiates who wanted to join a monastic community agreed to submit to that teacher’s legal, moral, and disciplinary leadership. They would provide personnel for religious practices for artisanal production and military protection. The monasteries were also centers of economic activity. All students paid the monastery, in cash gifts or in labor. Sometimes local authorities transferred to the monastic teacher such secular powers as collecting taxes or punishing criminals. Wealthy women were active as patrons of monasteries up and down the economic hierarchy. They both offered gifts of gold, valuable manuscripts, lamps, and herds, and they worked in the monastery’s fields. Marriages were central to establishing lines of alliance and power. In many of these communities, multiple spouses – polyandry as well as polygamy – strengthened political and economic power. Long-distance relationships between monastic communities were nourished by the mobility of ordained men and laymen who moved about as soldiers, pastoralists, itinerant merchants and peddlers, and diplomats working on behalf of particular disciples and patrons.

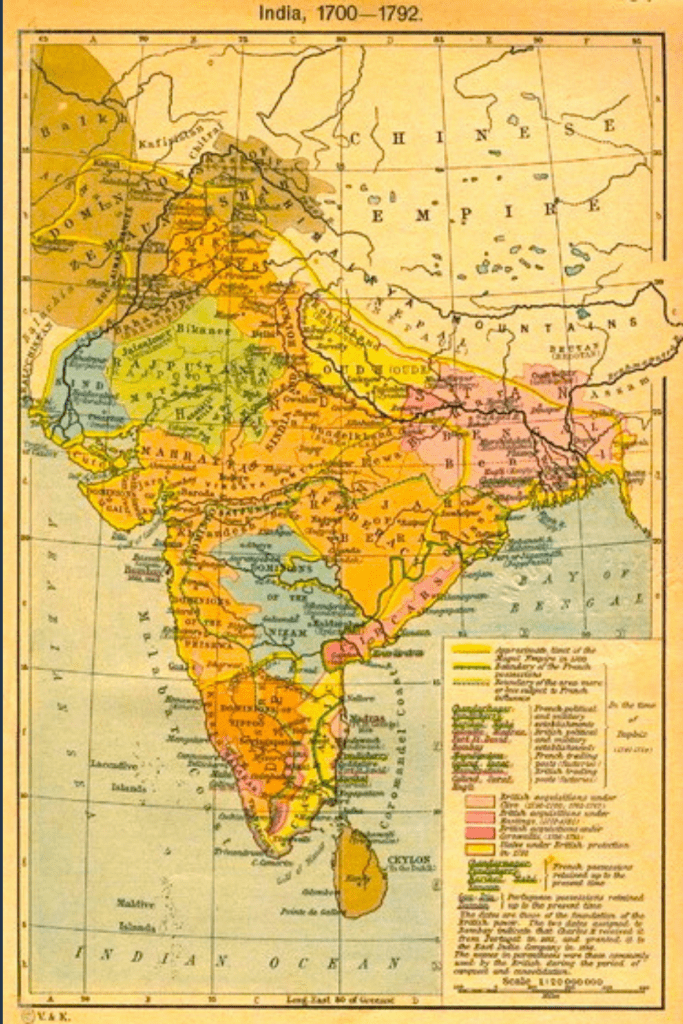

These connections among monasteries were dramatically reconstituted after 1765, when the English East India Company established its control over the subcontinent. After the 1830s, most lands of monastic governments located in the hills east of the Ganges Delta were taken over by European-funded tea plantations. Officers who worked for a soon-to-be-defunct English East India Company also used some of these lands to settle groups favorable to colonial control – gifting lands to Christian missionaries, settling some Vaishnava lineages in the Manipuri valley and ousting others. So they did not entirely dissolve the monasteries but made them give up their privileges.

By the 1850s, a harsh regime of work arrived to make tea plantations here a profitable enterprise for European planters. Large numbers of women and female children were brought from parts of central India to pick tea and work in these plantations. In 1869-70, some older monastic lineages pooled resources to liberate the predominantly female laboring population from the brutality of some of these plantations. The British-led military fraternity responded with an ideological war followed by a military war. The administrative aftermath was to isolate the entire belt of tea-planting lands from the monastic order. After 1871, when the Buddhist monks and Vaisnava-Saiva teachers were prohibited from working on or holding lands in the tea-planting regions, Christian missionaries took over.

This extension of colonial control radically dispossessed the monastic daughters and widows of the rights to landed property and authority that they had previously enjoyed. Yet this dispossession, along with the similarities of monastic communities among diverse religions, has gone unnoticed by modern historians of India. The intervening century has created other investments in the land, and none of the present investors wants the past owners and cultivators remembered. And of course, Christian missionizing has also authorized the erasure of the past because it is designated as “barbarian.”

Professional historians of India (and Bangladesh after it was founded in 1971), even when they were not trained in missionary-funded schools and colleges during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, looked upon the complex history of the terrain through lenses similar to the colonial authorities. Pre-colonial societies were “feudal” and colonial rule was equated with modernity and industrialized progress. These historians were extremely faithful to the spirit and letter of the colonial records. Their interpretation of the records echoed the colonial officials’ descriptions of once-resistant monastic subjects and adherents as “tribals” at best, and “savages” at worst.

After the 1970s, a younger group of historians expressed greater sympathy for the anti-state resistance movements they found in the same records. Better known as the Subaltern Studies scholars, these historians were, however, hampered by their lack of training in the multiple languages and literary traditions essential for uncovering the story of the multiple dispossessions practiced in the region that came to be called Northeast India. The result was therefore the same: postcolonial historians too failed to see through existing categories of “forest” or “tribal” rebels. If I had to sum it up, I would say that the cultural and financial successes of tea-drinking since the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have ensured a collective and permanent failure of memory among postcolonial historians. That amnesiac disregard of the past is especially dense around the various women who supported monastic governments in the past.

So when post-colonial, independent, democratically elected Indian governments allow their own military or paramilitary officers to evade judicial process after they rape and torture women from these eastern communities, they betray the extent to which such governments continue the practice of the dispossession of women and the erasure of women’s important roles in the history of the region and of the links that joined the people living in Northeast India as “friends.” Historians can refuse to be complicit in this dispossession by telling their stories

Indrani Chatterjee, Forgotten Friends: Monks, Marriages, and Memory in Northeast India

Sanjib Baruah, India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality (1999). Written by a political scientist attempting to explain the ethnonationalist (and anti-refugee) movement that sprang up in late 1970s in Assam, one of the seven provinces of Northeast India. The movement lasted for at least two decades. The author departs from other political scientists in taking a longer view of the politics, beginning with the colonial formation of the province of Assam from 1874.

The women missing from that discussion are heart and center of the work of a historically trained journalist writing non-fiction, Sudeep Chakravarti. I found many of the young girls at the center of his travel account, Highway 39: Journeys Through a Fractured Land (2012) simply heart-breaking. The societies described here are in another set of provinces — Nagaland and Manipur — that make up Northeast India.

The police-state described in those stories is encapsulated in the Government of India’s Armed Forces Special Powers Act that is operative in Manipur. A women’s peace movement has grown up against the violence that marks this model of governance there. One woman, Irom Sharmila, has been the symbol of that peace movement and is the subject of a biography by Deepti Priya Mehrotra, Burning Bright: Irom Sharmila and the Struggle for Peace in Manipur (2009). Irom Sharmila went on a fast-unto-death asking for the repeal of the AFSPA since 2001, was arrested, force-fed, released, and has been rearrested again.

A broader history of the women’s struggles of the twentieth century can be found in Geraldine Forbes’ Women in Modern India (1995).

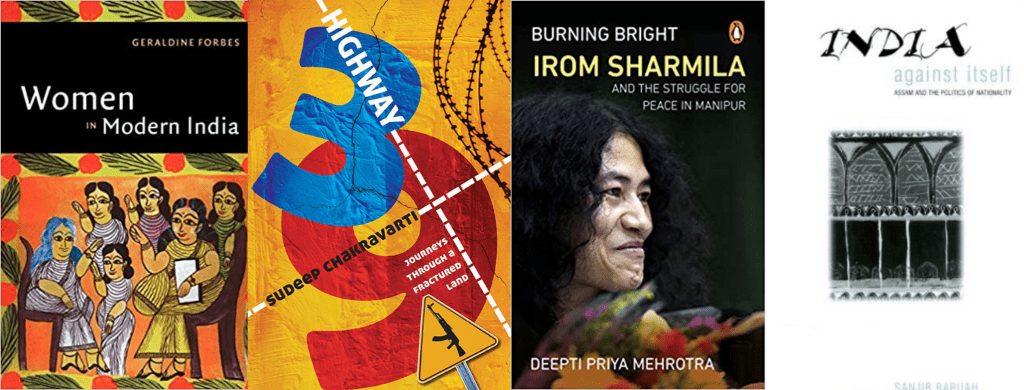

Feature Photo:

Kamakhya Temple, Guwahati, Assam. A famous site of goddess-worship known as Sakta Hinduism, on the river Brahmaputra.