Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery, which was established in the mid-1800s, is located in a quiet neighborhood on the east side of the city. The property is separated from the city center by busy highways and rapidly expanding housing developments. Its black, metal gates create an unassuming boundary between the hundreds of crumbling grave markers inside and a two-lane road many local dog-walkers enjoy. And yet, just a couple steps inside, centuries of stories belonging to women, men, and children from around the world begin to unfold.

A visit to the Oakwood Cemetery provides a window into the many lessons buried in historic cemeteries. One the one hand, its gravestones shed light on Austin’s history of socioeconomic inequality and discrimination along racial and religious lines. At the same time, they testify to the rich cultural diversity of the city, shaped by centuries of migration from across the US and across the world. Finally, they honor the memories of the people, young and old, who combined to build Austin.

The physical orientation of the cemetery provides the first insight into Austin’s long history of socioeconomic inequalities. This cemetery follows a grid-pattern, forming a matrix of ten major horizontal lanes intersected by six vertical paths. However, there is no uniformity within the various sections. Subtle differences are expected, such as personal touches in decoration, to honor the deceased individual. Walking along the paths–some paved, and some not– allows visitors to note broader disparities between individual zones. For example, the gravestones concentrated towards the center of the cemetery appear larger and better cared-for and therefore easier to read. The monuments along the periphery are generally smaller and often broken.

![A cracked gravestone bearing the inscription: "Elizabeth B. Consort of Rev. J. Haynie Born in Georgia, [illegible] 1787. DIED Oct 4, 1863."](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_38141-768x1024.jpg)

Studying the disparities between well-kept gravestones and those that appear more neglected sheds light on the differing economic resources of Austin’s citizens throughout its history. Oakwood’s various expansions helped explain this layout. Over time, the city of Austin added several new sections to this property. There were at least seven additions to the cemetery in 1866, 1875, 1889, 1892, 1895, 1901, and 1910. Sometimes, an expansion was officially designated for a specific group, such as individuals belonging to a certain religious denomination, or people of color. For example, the Jewish temple Congregation Beth Israel purchased designated sections for Jewish burials in the late-1800s. The clear differences in size and condition of burial monuments between the sections of the cemetery illustrate that not all groups received the same care or resources.

![A broken headstone bearing the partly legible inscription: "In [illegible] My only beloved son Mark Wilson. Born in Dublin Ireland. Feb. 19 1844. Murdered in Austin."](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_38361-1024x768.jpg)

Oakwood’s gravestones also reveal several clues about the city’s history of racial discrimination. Significantly, an area near the Navasota Street entrance was officially assigned to people of color. The grave markers in this sector appear smaller and more worn where they survive at all. Historic markers acknowledge that because the city tended to prioritize the wealthy, European-descendant patrons, the zone near the Navasota Street entrance became a “catch all” for poor residents and out-of-town visitors who died in the city as well as Mexican American and Black women, men and children. Because of this prejudice, the exact identities and locations of many of the graves in this area cannot be determined.

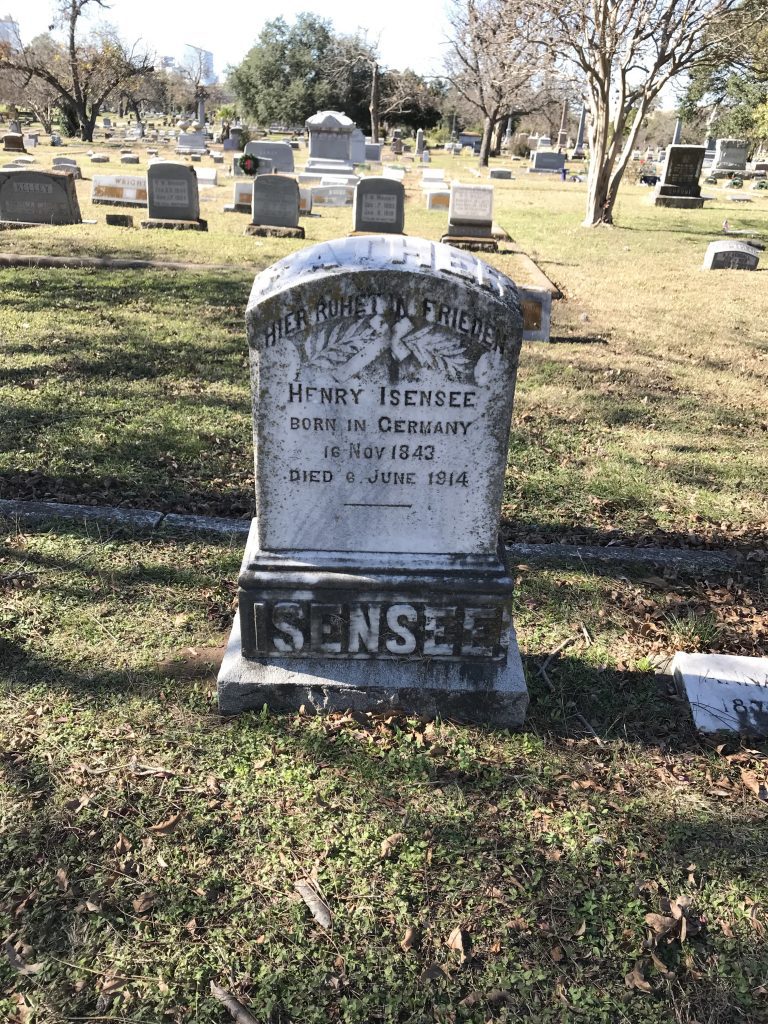

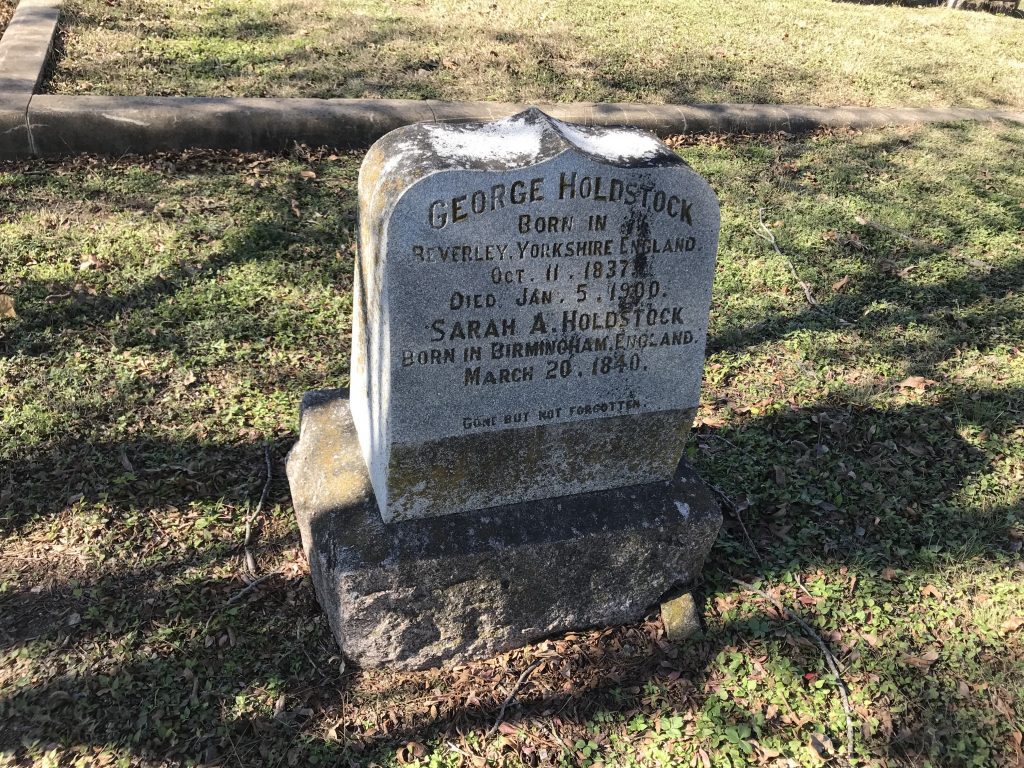

At the same time, the information recorded on these headstones provides a testament to Austin’s history of cultural diversity. One way to see this is by examining the multiplicity of languages used in the inscriptions. Less than two meters inside the Comal Street entrance, there are several small, almost illegible grave markers. Closer examination reveals names that suggest that the deceased individuals were of Mexican or Mexican American heritage. The inscriptions themselves (including birth and death dates, places of origin, and sometimes short prayers) appear in Spanish. Other gravestones throughout the cemetery feature Latin, German, and Hebrew messages, which shed light on the large immigrant communities that have shaped Austin’s history.

![A gravestone bearing the inscription: "Gertrude Alten, GEB D. 19 Juni 1887, GEST D. 12 July 1887. Seelig sind die reines herzen sind, denn sie werden Gott [schau?]."](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_38211-768x1024.jpg)

The insignia featured on many of the grave markers from these immigrants also provide important insights into the cultural values of the deceased. Some stones feature prayers, floral or animal designs, and even symbols associated with specific community organizations. For example, a prominent symbol for the Woodmen of the World (a fraternal organization) appears on the headstone for Aurelio Pena.

![A headstone featuring a carved butterfly symbol. The inscription reads: "Edgar W. Forster Born Nov. 5, 1880 Died Apr. 2[illegible]."](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_37531-1024x768.jpg)

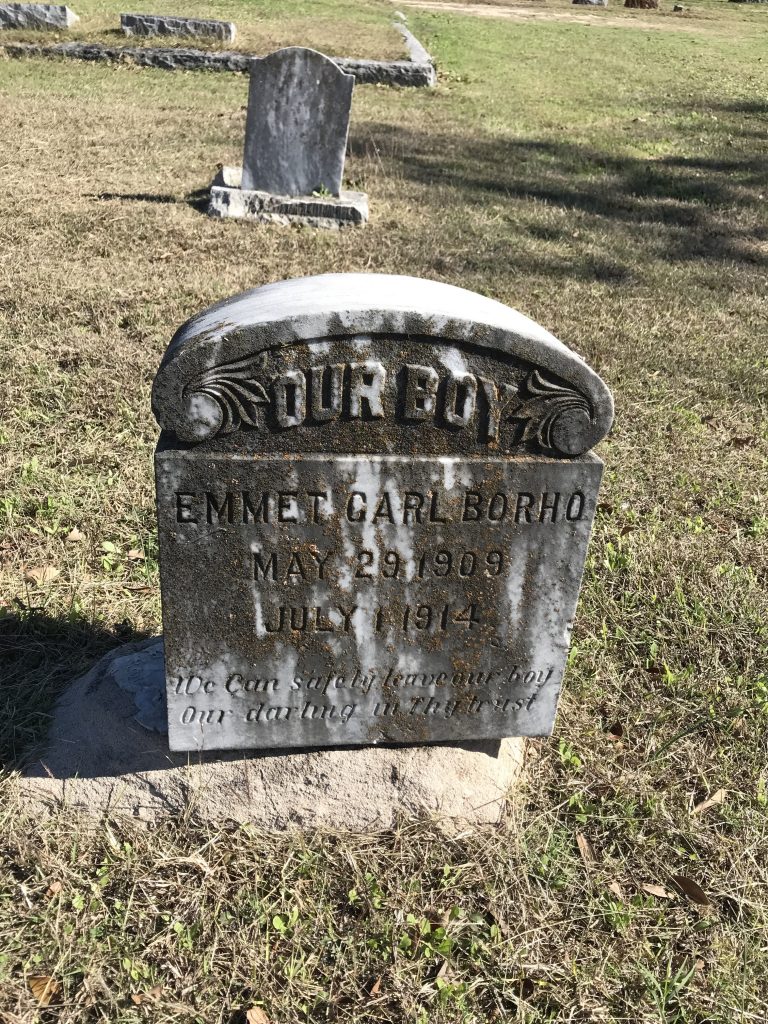

Finally, the burial plots fundamentally pay tribute to the lives of Austin’s early residents. They are often arranged to reflect family structure, with husbands and wives next to each other surrounded by children, grandparents, and even aunts and uncles. Many gravestones prominently feature birth and death dates. This information demonstrates the tragic prominence of infant death through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some such monuments feature affectionate nicknames or detailed carvings of children and animals. These deteriorating stones serve as memorials to lives cut short.

Oakwood cemetery is a testament to the lives of Austin’s past residents. Even a leisurely stroll through the shady, tree-lined lanes reveals how much twenty-first century visitors can learn from the graves. From the social and cultural hierarchies that lay behind the cemetery’s organization, to the memories and practices that family members preserved on the headstones of the deceased, these monuments contain vital information about this city’s history. They also tie the heart of Texas to vibrant patterns of global migration.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.