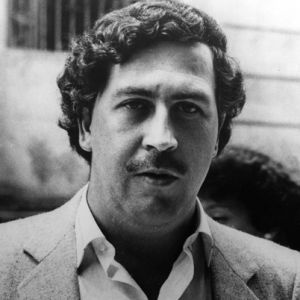

Seen through the eyes of Steven Murphy, the DEA agent whose voice-over narrates the new Netflix series Narcos, Colombia appears to viewers all over the world as a land of sicarios (hired young assassins), putas (whores), and malparidos (the fucked-up). In short, Colombia becomes the quintessential Macondo of Gabriel García Márquez. The Colombian Nobel prize winner is renowned for introducing magical realism as narrative technique: the journalistic description of reality, in which the supernatural and the strange are woven together into matter-of-fact accounts. Narcos introduces the viewer to one of Macondo’s sons: Pablo Escobar, a savvy entrepreneur who was to become one of the most powerful drug lords in the history of the world, the leader of the Medellin cartel. In the early 70s, Escobar went from smuggling cigarettes and TV-sets to exporting cocaine into Miami. By the early 80s, Escobar was transporting one ton of cocaine per day.

Narcos describes the transformation of both Colombia and Murphy. Before Escobar, Colombia was corrupt but poor. But with the arrival of Escobar’s billions, Colombia became a bustling, cosmopolitan hellhole. The narrative arc of Murphy’s metamorphosis is also cast in very simple terms. He was originally a naïve agent chasing after potheads in Miami. Once in Colombia, however, Murphy goes native. In the last episode, Murphy resolves the dispute over a mild car accident by shooting at the other driver, while his gringa wife and Colombian baby girl (who had been left orphaned in a murderous rampage by Escobar’s minions and who Murphy casually picked up to raise) witness in horror Murphy’s new penchant for blood and lawlessness. It is in the wake of this shooting that Murphy’s wife begs Murphy to take the baby and go back home (to the US). A nonchalant Murphy replies that home is now Colombia.

Viewers do not get to witness the effects of Colombia in the transformation of two other secondary characters working at the US Embassy in Bogota: the CIA chief agent and the marine representative of US Southern Army Command. These two gringos have already been “seasoned” and therefore understand that Colombians are moved only through the barrel of a gun. Narcos therefore explicitly suggests that there is a fundamental difference between an uncivilized Latino south and a peaceful Anglo north that is bridged when Anglos get to live for a long time among the savages. Narcos has the three representatives of the US government embracing every aspect of Colombian violence while proving incapable of learning a single word in Spanish over the course of ten episodes.

There is something, however, that Narcos gets right. The series shows the use of torture, terror, and electronic surveillance in the making of the modern US Empire. For three episodes, Escobar operates freely in the USA. Murphy documents the murder of some 3,000 black and Latino narcos in the streets of Miami in the late 70s and early 80s. This blood bath of expendables did not budge any US politicians into action. It was, however, a photo of Escobar moving crates on an airfield of Sandinista Nicaragua that persuaded Reagan to up the ante. It is only then that Murphy moves to Colombia as DEA agent and the CIA and the marines begin torturing Colombians as well pursuing the electronic surveillance of Escobar’s phone communications. The show documents with great accuracy how before Iraq, there was Colombia.

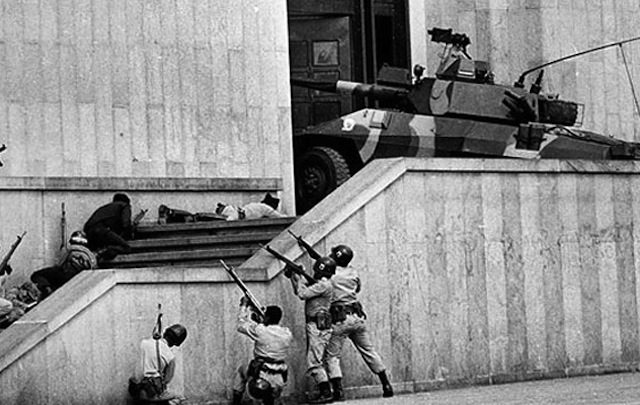

Narcos has Escobar’s minions pitted against a tiny elite of incorruptible bilinguals (politicos and army officers) in a violent struggle over control of the Colombian state. Every event in Colombian politics in the 80s and early 90s is made to revolve around the implementation (or lack thereof) of extradition of narcos to the USA: the assassinations of the Chief Minister of Justice Rodrigo Lara Bonilla and the presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galan, the election of Cesar Gaviria as President of Colombia, the M19 attack on the Palace of Justice of 1985, and the constitution of 1991. The picture is so skewed as to become absurd.

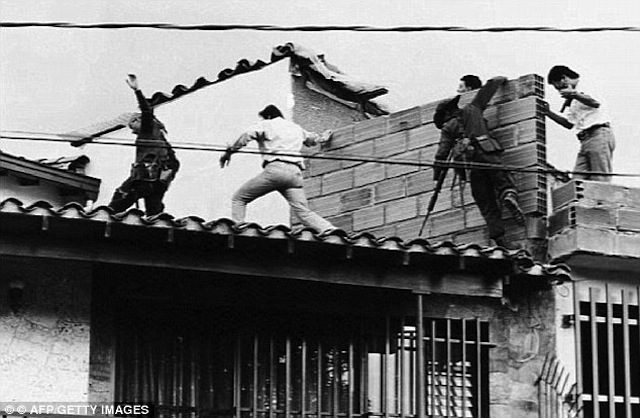

The M19, a social democratic guerilla movement that led the attack on the Palace of Justice and whose negotiated incorporation into the political process led to the Constitutional Assembly of 1991, is turned in a clownish club of dilettantes. In one episode, Narcos has a strangely taciturn, sad, and inept M19 leader (clearly not the historical leader of M19, Jaime Bateman, who was an exuberant Afro-Colombian who loved both life and politics) break into a museum with his voluptuous lover to steal Bolivar’s sword, a symbol of unfulfilled liberation, only to have the leader hand in the sword to Escobar in the next episode. The M19 was by far the most popular political movement of the 1980s, equipped with a regular army 2,000 strong engaged in a war of positions with the Colombian army in the Valley of Cauca. But in Narcos it is portrayed as a tiny urban cell doing all of Escobar’s dirty business. According to Narcos, the M19 attack on the Palace of Justice was financed by Escobar to have a cache of his papers, captured in a raid, burnt. This is nonsense. M19 seized the Palace to call attention to the systematic aerial bombardment of guerilla forces in the wake of a negotiated peace agreement with President Belisario Betancourt. The burning of the palace was the doing of the army, not the M19.

The great conflict of the 80s in Colombia was for sure messy. It did involve narcos, the state, urban guerrillas, and the USA. Yet the great protagonist of the 80s was the grass roots movement to transform the oligarchic Colombian regime into a viable constitutional social democracy. The movement partially culminated in the passage of the Constitution of 1991. Narcos completely distorts this process and by so doing overlooks the impulse behind the constitutional banning of extradition. The debate was not just over the threat of narco money corrupting politicos. It was far more ethically substantive: whose blood should be spilled in the global war on drugs and whose bodies incarcerated. This war is now being fought in Mexico and US ghettoes. The dead bodies of the war on drugs continue to be largely brown and the incarcerated ones black, while consumers in Palo Alto and Manhattan get to enjoy Netflix’s Narcos.

More on NEP about Colombian History:

Jimena Perry discusses two museums that represent the Colombian violence since the 1960s: the Hall of Never Again, a community-led memory museum in Colombia, and The Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia