This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

“Only in extinction is the collector comprehended,” wrote Walter Benjamin, in his now widely read essay on book collecting.1 What holds a book collection together, its unifying force, is the personality of the collector themselves. A “living” collection grows, is rearranged, books are lost or disappear, and found again. All the while, the collector orchestrates behind the objects. “[T]o a true collector,” Benjamin reminds, “the acquisition of an old book is its rebirth.”2 The desired object is reborn into the ordered obsession of the collector. Inversely, however, when a collector passes away—“in extinction”—the objects themselves are often left to tell the story of the collector. This is one such story.

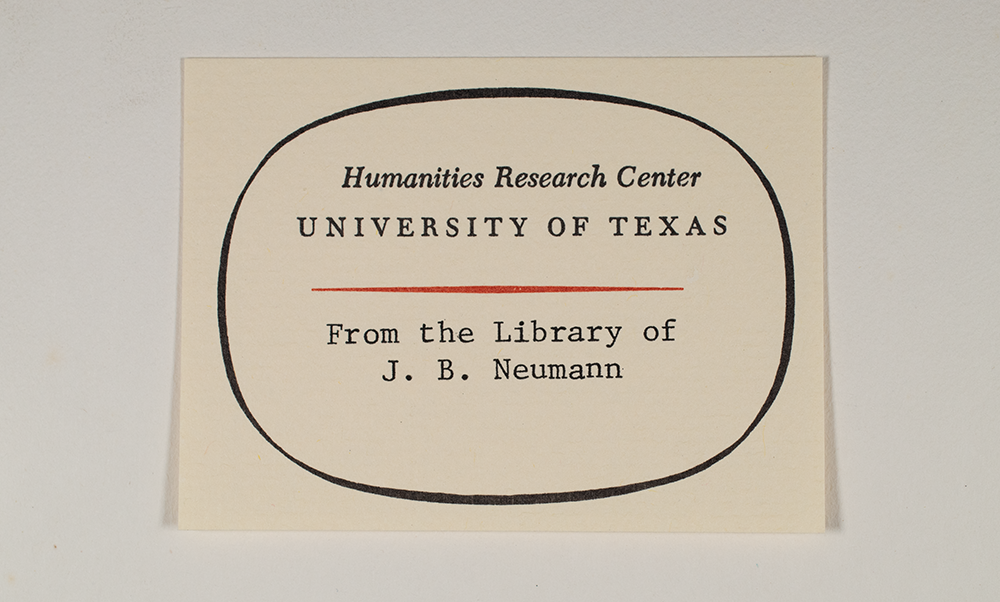

In 1962, nearly one year after the German-Jewish art dealer, gallerist, and publisher J. B. (Israel Ber) Neumann (1887-1961) had passed, The University of Texas at Austin purchased his personal library for $10,000, a small sum for what today could easily be valued at tenfold that amount. The director of the University Art Museum at the time, Donald B. Goodall, wrote that Neumann’s “Art and Literature Library,” as it was first introduced in a wired message from the director at the Museum of Modern Art, “may form a nucleus of research and publication around one of the major centers of critical and dealing activity during the important years when Modern Art was being introduced to this country.”3

University of Texas Humanities Research Center bookplate, “From the Library of J. B. Neumann,” in Guillaume Apollinaire, The Cubist Painters (New York: Wittenborn and Company, 1944). Harry Ransom Center, ND 1265 A62.

Goodall had good reason to be optimistic about the purchase. Neumann was a pioneering figure in the Berlin art scene during the rise of the German avant-garde before and after the first World War. He championed the likes of Max Beckmann, exhibited members of the now infamous artist group “Die Brücke,” and hosted the first ever exhibition of Dada painting and sculpture—all while opening new galleries in Munich, Düsseldorf, and Bremen. He published the expressionist journal Der Anbruch and gained renown through his periodicals J.B. Neumanns Bilderhefte and later Artlover. Risking all, he would immigrate to New York City in 1923 to help usher in the first wave of modern German art in the United States, founding “J.B. Neumann’s Print Room,” later renamed to the “New Art Circle.” He supported numerous young artists and German immigrants and helped establish a vibrant culture around art on the then nascent 57th Street. Fighting tirelessly for what he lovingly termed “living art,” Neumann collaborated with the most important dealers, collectors, and artists of his age.

Today, however, Neumann’s name is far less known—and his personal library all but dissolved. Originally acquired at over 4,500 items, fewer than 100 are now cataloged at the Ransom Center. And while the reach of his personality can still be found in the footnotes, forewords, and prefaces to many important publications and catalogs on modern German art—and especially on German Expressionism—the man’s remarkable character has disappeared behind the very artists he helped promote. Other German art dealers, such as Alfred Flechtheim and Curt Valentin, are more prominently remembered for their role in establishing an international market for modern German art. The story of Neumann’s library, then, is not only another footnote to an otherwise obscure figure but holds the promise of rehabilitating one of the most important art dealers of the twentieth century.

If not for a lucky antiquarian find, this promise may have disappeared forever. As it stands, even before I knew his name, or anything of his personal library, I acquired nearly 200 German-language books that had been deaccessioned by UT, all belonging to Neumann. Thus “reborn” into my own collection, the stories these books seemed to tell through their inscriptions, marginal notes, and extensive focus on the graphic arts sparked a growing curiosity into the man. Who was he? How had his books arrived in Austin, Texas? Were they part of a larger library? And what role might they play in telling a more complete story? In the summer of 2025, with these questions in mind, I began a research fellowship at the Harry Ransom Center on an adjacent topic. Could I perhaps, I thought, as an aside to my primary research, unlock some of the mysteries of Neumann’s books?

It is a rare stroke of fortune when a researcher’s hopes and the hard truths of archival research align. Confirming my suspicion, an initial discovery at the Ransom Center proved among the most important: the “acquisition letters” on the purchase of Neumann’s library. Part of the Center’s own archive, the two institutional letters argue for the importance of the library and describe its contents, which consisted of “folios, monographs, critical works, catalogues and periodicals.” The first letter, dated January 1, 1962, broadly introduces the collection and highlights Neumann’s historical significance:

During the years after the first World War, J. B. Neumann was one of a small group of believers in the growth of modern art ideas, and coming here from Germany, his gallery was one of three or four seminal points in the emergency of contemporary art in the United States. His library was a working apparatus and supported the exchange of art works and correspondence which occurred between Neumann and many of the world’s most important innovators, among them Beckmann, Rouault, Kandinsky, Max Weber, and the German Expressionists. After the team of Stieglitz-Steichen, he can be considered the most influential dealer-personality to have propagated the cause of modern art in America.

The second letter, dated February 6, 1962, was intended to give a more detailed account of the collection. It lists a selection of “Early Editions” and “Rare Items,” along with an estimate of their current market value. For the researcher, these letters prove quite substantial: they give a picture of the library in its entirety; help confirm which books are still catalogued at the university; and can even help in confirming which books now in private hands may have once belonged to the collection.

After this first success, staff at the Harry Ransom Center helped to locate a second file containing various ephemera, mostly notes and small drawings, that were withdrawn from J.B. Neumann’s books as they were being cataloged.4 While only consisting of a few items, this file provides an initial sense of Neumann’s personality and character. One can easily imagine the expansive network of museum directors, investors, artists, and friends that took shape as Neumann established himself in the United States after 1923. One finds, for example, a sketch for a business proposal drafted on a hotel notepad (“Mr. Moir, Let’s start a picture business”); a charming watercolor by the German-born artist Vita Petersen; a letter from the membership committee of the American Artists’ Congress, signed by the graphic artist Lynd Ward; a beautiful endpaper from the collection of Richard Beer Hoffmann, an Austrian-Jewish dramatist and poet; and a publisher’s letter detailing the process for reproducing Max Beckmann’s illustrations for a post-war edition of Goethe’s Faust.

After moving to the United States, Neumann remained in close contact with his European associates, even if his status as a Jewish art dealer made it increasingly difficult to maintain his status quo in Germany. Nevertheless, after a forced interruption from 1933 until 1945 during the reign of the Nazi regime, he resumed his visits as often as his finances would allow. And he always made a point to bring back as many exhibition catalogs as possible, filling the shelves of his library with memories from his trips. In a letter from 1947 to a Swiss museum director he writes: “Kataloge sind so wichtig weil wir das Museum mit uns nach Hause nehmen können. Als ich die vielen Jahre von Europa abgeschnitten war, lebte ich (seelisch-kuenstlerisch) nur von den Katalogen” [Catalogs are so important because we can take the museum home with us. When I was cut off from Europe for many years, I lived (emotionally and artistically) only from catalogs].5

Of little financial value in and of themselves, Neumann’s catalogues spanned a period of nearly fifty years, documenting the rise of modern art along with sometimes substantial notes on his buying and selling practices. Unfortunately, the catalogues once at UT were almost entirely deaccessioned or lost; only a small remnant is now in private hands. Some of the most significant “Early Editions” and “Rare Items,” though, do remain. The Center holds, for instance, Neumann’s copies of the 1532–1534 edition of Albrecht Dürer’s Human Proportions, a masterpiece from one of Germany’s most famous artists, and Richard Huelsenbeck’s Dada Almanach (1920), an early and now quite collectable anthology of Dadaist texts. Although Neumann’s library can no longer be salvaged or reconstructed in full, there is a meaningful nucleus. In the fragments of the library, we can glimpse something of the whole.

When Neumann opened his first gallery, “Das Graphische Kabinett J.B. Neumann,” in Berlin in 1911 (founded in 1910), his primary focus was to support artists “young and new.” In a promotional brochure, now held in the general collections at UT and from Neumann, he reproduces an excerpt from the first painting exhibition he hosted in 1913: “Wir wünschen rechtzeitig die Teilnahme des Amateurs auf die Arbeiten der Jungen zu lenken und gerade bei uns vermag dieser das schöpferische Moment des Sammelns zu genießen: die Freude Unbekanntes zu entdecken” [We wish to opportunely direct the participation of the amateur towards the work of the young, and precisely with us he may enjoy the creative moment of collecting: the joy of discovering the unknown].6

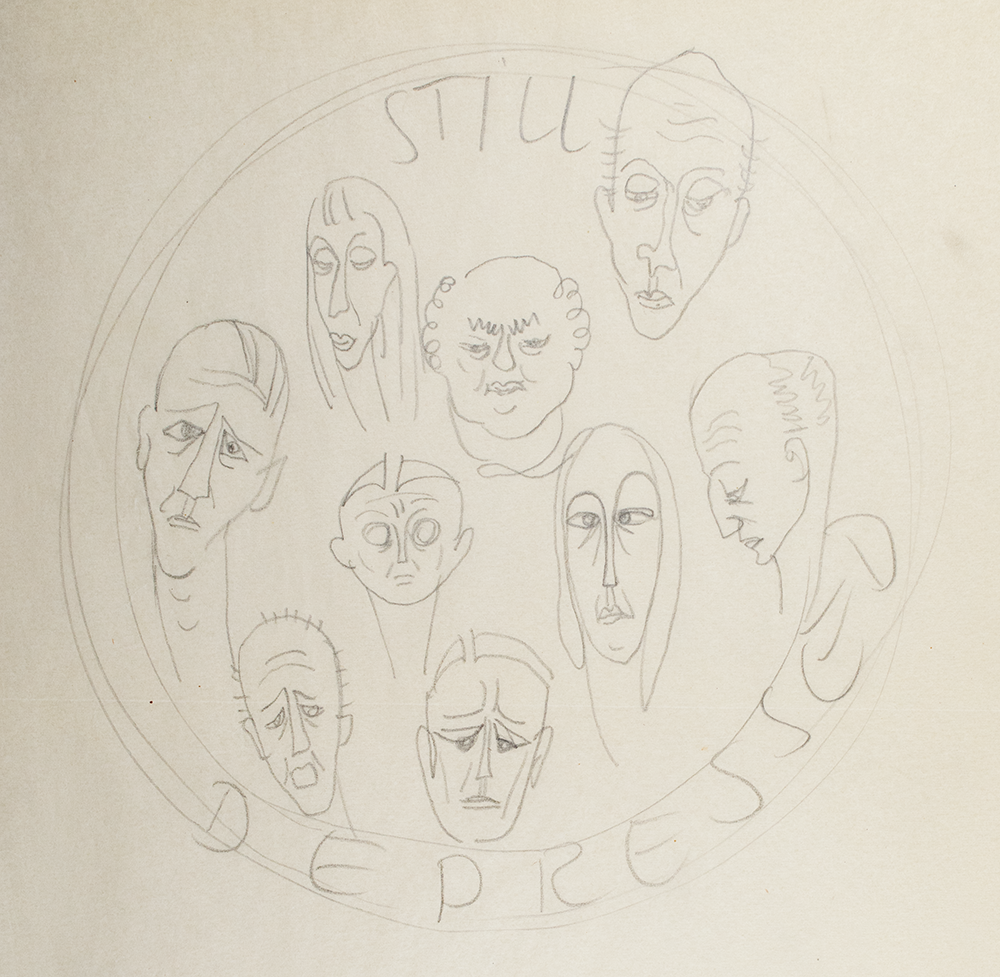

Neumann maintained a lifelong passion not only for the “creative moment of collecting,” but also for his professional task: nurturing “the commerce between artist and admirer,” especially involving works that were still unknown. As an art dealer, he thereby had a hand in building some of the most important private and public collections in the United States while also supporting the artistic and financial efforts of his artists. Neumann’s empathy comes into focus in a folded sketch he composed under the heading “Still Depressed.”

Expressionist in tone, the sketch depicts a group of people, perhaps artists under Neumann’s patronage. Their long El Grecian faces emanate melancholy and capture the weight and isolation of the individual. The plight of the artist is expressed alongside Neumann’s own disposition as an art dealer: despite his constant striving, his artists are still discontent. Perhaps they had hoped for more immediate success? Perhaps their financial burdens are still too great? Worthy of further study—it lies outside this short essay, for example, to match each face to a corresponding artist—this sketch raises questions on the role of the art dealer and shows how personally involved Neumann was in the life and work of his artists.

Neumann’s great love for art often manifested in the practicalities of his relationships. Whether mediating commissions, dealing directly to the public, or securing works for exhibitions, his life intersects with many well-known personalities of the art world. One such figure is the German illustrator, painter, and satirist George Grosz. Grosz grew to international fame, alongside John Heartfield, as a central agitator in the post-war Dada movement in the Weimar Republic and continued to find success after emigrating to the United States in 1933. A master draftsman, he captures in his drawings the contradictions of bourgeois city-life, confronting his viewers with the bitter, and often dark underside of modern society.

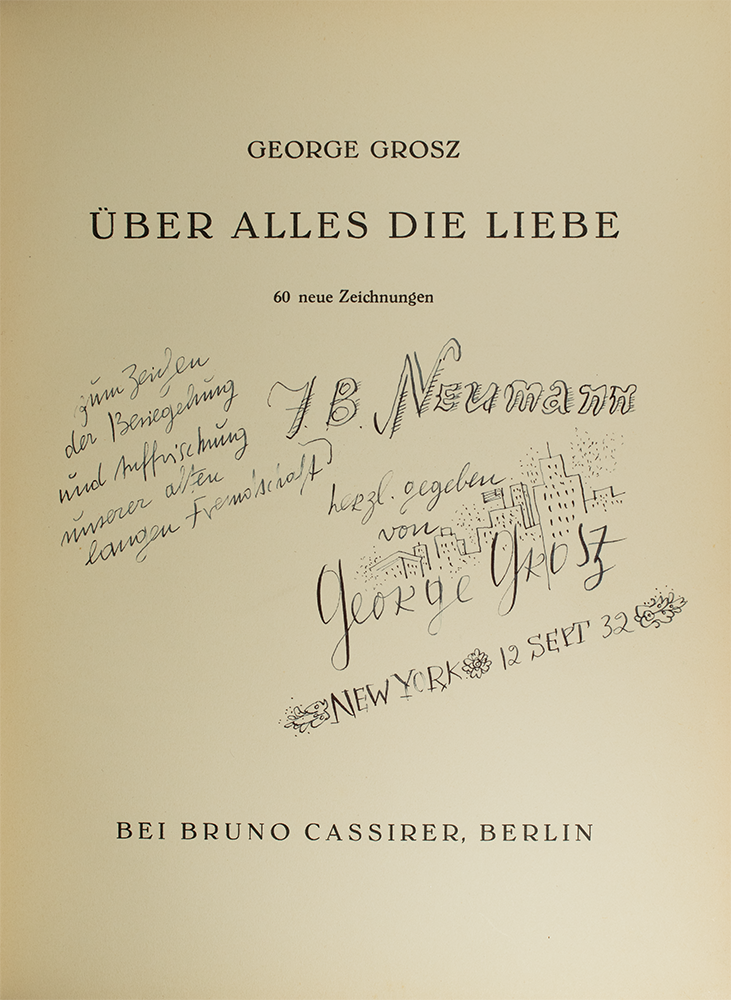

In the Center’s catalog, five books associated with Grosz note Neumann provenance.7 Grosz and Neumann had originally collaborated at the height of the German avant-garde in Berlin, where Neumann also sold and exhibited works by Grosz. Significantly, it was Neumann who hosted some of the first Dada evenings in Berlin and the first ever exhibition of Dada painting and sculpture. Books from Neumann’s library point towards an intimate friendship that was important for both. Their relationship is wonderfully on display in an inscription to Neumann in Grosz’ book Über alles die Liebe, a collection of drawings published by Bruno Cassirer in 1930:

The inscription reads: “Zum Zeichen der Besiegelung und Auffrischung unserer alten langen Freundschaft” [As a gesture of confirmation and renewal of our old, long friendship]. Already in 1925, shortly after moving to New York, Neumann had offered “to do all he could” to help Grosz, if he ever wanted to follow. Grosz had long been fascinated with the United States, as reflected in childhood sketches and stories about the American West, and when in 1932 the political situation in Germany was faltering, he leaned heavily on his “long friendship” with Neumann. Grosz would emigrate to the United States with his family in 1933, only shortly before Hitler came into power.

No longer able to work in the same leftist-satirical vein that had brought him fame in Germany (most notably with the journal Simplicissimus and later with the Malik Verlag, the anti-fascist publishing house founded and run by Wieland Herzfelde, John Heartfield’s brother), Grosz sought meaningful work and renewed artistic impulse in a new political environment. A snapshot of Grosz’ new world can be partially reconstructed from sources held at the Ransom Center. These sources also show how prominent Neumann was in New York in the early 1930s and point towards possible avenues for further research.

The first of these items is an inscribed copy of O. Henry’s The Voice of the City (1935), published by Georg Macy for The Limited Editions Club, which Grosz had set aside for “J.B.N.”—Neumann. Lauded in the introduction as a “great European artist,” Grosz produced twenty haunting watercolors and small illustrations throughout, showing his developing style and eagerness to adapt as an American artist. By good chance, the Center also holds the files of publisher Georg Macy, which contain letters detailing the behind-the-scenes financial negotiations with Grosz and the first proofs of his watercolors. And in good archival fortune, examining these files led me to evidence of a more substantial link between Grosz and Neumann: a simple, yet compelling art school pamphlet. Before moving to New York, Grosz placed his hope in the hands of his old friend, and Neumann suggested opening an art school together with Maurice Sterne, the well-known American painter and sculptor, to help finance Grosz. The ”Sterne Grosz Studio,” directed by Neumann, only lasted from 1932 until 1936 but serves nonetheless as a prime example of how Neumann fought not only for the physical survival of modern works of art but also for the financial and political survival of the artists themselves.

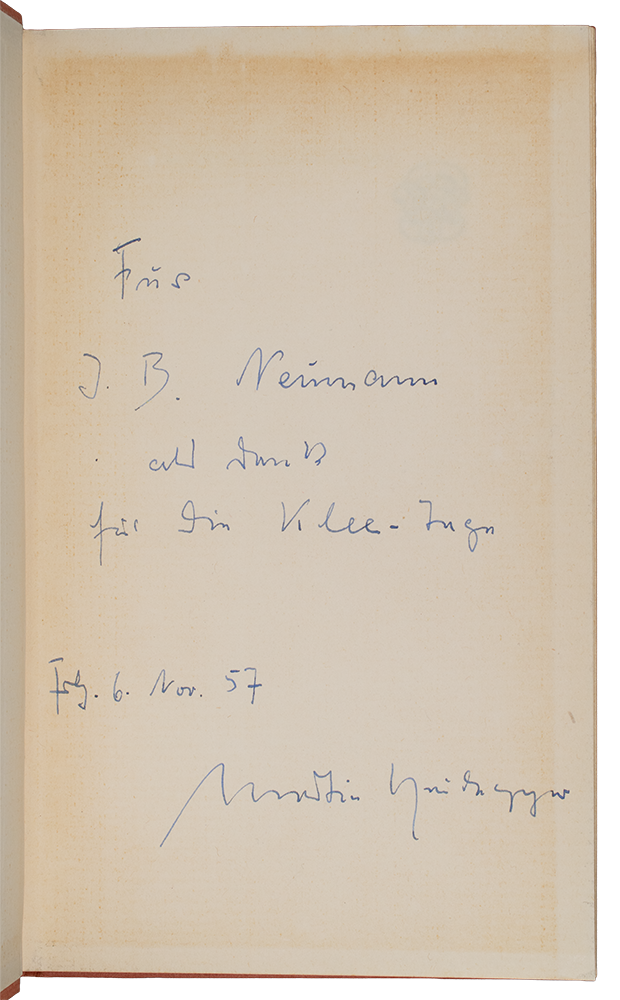

As an art dealer and personality, Neumann’s reach far exceeded what is documented today. In fact, he was not only in frequent communication with the most important publishers and artists of his age, as the example of Macy and Grosz shows, but was also known and respected beyond the strictly artistic sphere. One of the most surprising—and significant—discoveries from Neumann’s library is a collection of inscriptions to him by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger: two from 1953 and one from 1957. While Heidegger was not known to be an art collector, his writings on art and poetry— especially his essay “On the Origins of the Work of Art”—are central contributions to twentieth-century aesthetic theory. His magnitude in the world of philosophy cannot be overstated. So, what had the world-famous philosopher wanted with a Jewish art dealer from New York, especially given Heidegger’s troubling position on the “Jewish Question”?

Not much can be gleamed from the two inscriptions from 1953, except the likelihood that Neumann had personally visited “Heidegger’s hut,” the infamous cabin near Freiburg in the Black Forest, while on one of his yearly trips to Europe. The third inscription however, dated November 6, 1957, is revealing. It reads: “Für J.B. Neumann, all Dank für die Klee-Tage” [To J.B. Neumann, all thanks for the Klee-days]. Paul Klee (1879-1940) had already reached legendary status by the 1950s, only shortly after his death. Neumann, who writes with embarrassment how he had underestimated Klee’s abilities when they first met, eventually saw Klee as the artist closest to his own heart. In addition to his activities as a dealer and publisher, Neumann was a respected lecturer, holding public talks on Klee, among many others. Perhaps Heidegger himself had sought Neumann’s insights on the artist?

Whatever the specifics, it seems all but certain that Heidegger and Neumann met in 1957 and discussed Paul Klee. Adding to this, it is known that Heidegger, in anticipation of a 3rd edition of “On the Origins of the Work of Art,” wrote down his “Notes on Klee” sometime “between Summer 1957 and Autumn 1958”—exactly the period when Neumann met with him.8 Is it possible, then, that Heidegger’s turn towards Klee, a significant development still in debate, was encouraged by Neumann? Could further investigation lead to a more substantial link between Neumann and Heidegger’s philosophy of art? These questions alone suggest a need for further research into Neumann’s legacy. And the encounters with Heidegger and Grosz are merely two examples among many.

Taking Neumann’s library as a starting point for research lends significance and context to what otherwise could quickly be overlooked. This was my experience when, while searching through the files at the Ransom Center on the writer and art collector Nancy Wilson, whose published essay on Paul Klee had piqued my curiosity, I stumbled upon a pamphlet, with a note in Neumann’s hand.9 To my surprise and delight, I could now see an entire life unfold in the details of this pamphlet: A pensive and seeking photograph; charming correspondence with a touch of business flair: (“Dear Nancy, at last I got your address. I love your essay on Klee—I am longing to see you again […] I have some beautiful Klees!”); the distinct yet connected worlds of Germany and the United States; and a pioneering spirit who heralded some of the most famous artists of the twentieth century. This came with the realization that Neumann had an almost unfathomable, and certainly still underappreciated, impact on the world of modern art.

As an art dealer, J.B.—as his closest friends and patrons would call him—was of a different make than his contemporaries. For him, art was never merely a business, but more akin to faith or a religious experience. In fact, he identified more closely with the artists he supported than with the dealers with whom he stood in competition: “Most of the artists whom I have promoted have been Expressionists. I guess you could call me an Expressionist, too. If there is such a thing as an Expressionist art dealer, then I am it. What would that be? Well, let’s put it this way. It’s a dealer who is obsessed with the idea that selling a certain picture will not only save him from his landlord, but also save his soul.”10

Josiah Simon is an independent scholar, bookseller, translator, and teacher living in Austin, TX. He holds a PhD in German from the University of Oregon. Simon has taught German, humanities, and philosophy at various institutions across the United States and has conducted research at the University of Heidelberg, the Ruhr-University Bochum, and the Harry Ransom Center (UT-Austin). His recent scholarship has appeared in the Franz Rosenzweig Yearbook and he is an active contributor to the Hans Ehrenberg-Studien.

1 Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my Library,” in Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 67.

2 Ibid., 61.

3 Harry Ransom Center, HRC Archive, Box 545, Folder 35.

4 Harry Ransom Center, Manuscripts Withdrawn from Books, Box 1, AML 1.7

5 Ibid.

6 “Das Graphische Kabinett J.B. Neumann / Berlin 1910 – 1917.” Promotional Brochure. University of Texas Libraries, Library Storage Facility, 708.3 G767G.

7 Harry Ransom Center, NC 1145 G78; PS 2649 P5 V6 1935; PT 2638 W744 G4 1931; PT 2617 U43 D6 1921; NC 1509 G74.

8 “Special Topic on Heidegger and Paul Klee”, Philosophy Today 61.1 (Winter 2017): 7-17.

9 Harry Ransom Center, Nancy Wilson Ross Papers, Box 84.

10 J.B. Neumann, Confessions of an Art Dealer, unpublished, Museum of Modern Art, J.B. Neumann Papers, II.B.2.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.