By Tiana Wilson

After reading this book in three different graduate seminar courses, I can confidently argue that Marisa Fuentes’ Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive is one of the most important texts of our time, and a must read for anyone interested in overcoming the limitations of archival research. For many scholars of marginalized groups in the U.S., there remains a challenge in finding materials on our subjects because most of their records are not institutionalized. However, Fuentes offers a useful analytical method for extracting information from sources bent on erasing their existence.

Fuentes’ work contributes to the historical knowledge of early America through her focus on violence and how it operated during slavery and continues today through archives. She cautions scholars to avoid traditional readings of archival evidence, which are produced by and for the dominant narratives of slavery. Instead, she calls for a reading “along the bias grain,” of historical records and against the politics of the historiography on a given topic. In other words, she pushes historians to stretch fragmented archival evidence in order to reflect a more nuanced, complex understanding of enslaved people’ lives. In doing so, her work investigates the sometimes hidden intentions and power dynamics that frame people’s decision-making. Rather than placing our subjects within the categories of victims or victors, Fuentes encourages scholars to examine the “complex personhood” of everyday actions.

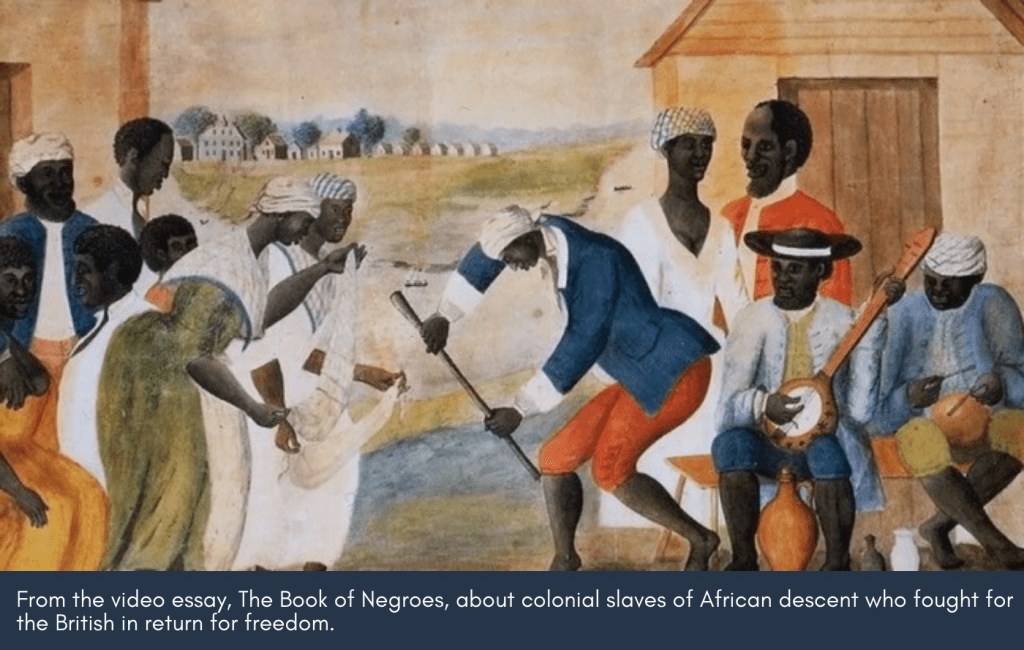

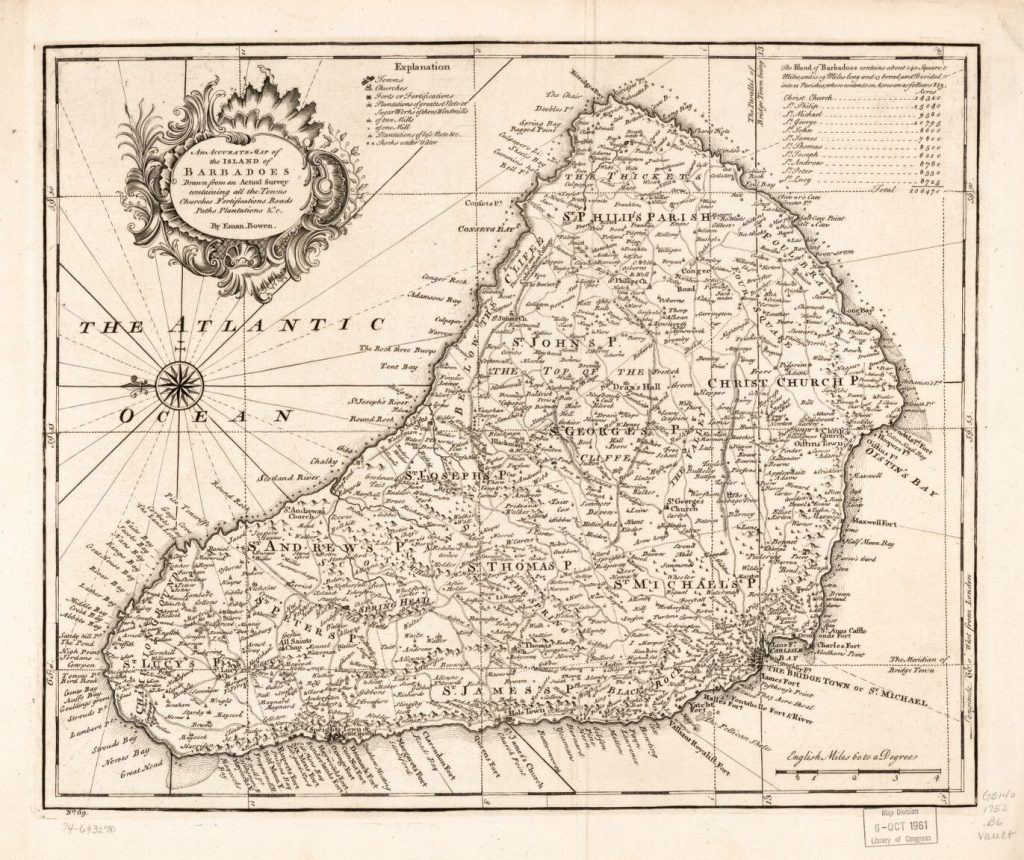

Dispossessed Lives provides a portrait of eighteenth-century urban slavery in Bridgetown, Barbados from the perspective of multiple black women. This includes black women’s experiences in public executions and violent punishments, their involvement in the sex economy, and their efforts to escape slavery. Fuentes makes two interventions into the scholarship on slavery in the Atlantic world. First, she challenges the narrative that plantation slavery was more violent than other forms of bondage, and argues that urban slavery was just as brutal. Second, with a focus on the centrality of gender, Fuentes’ study reveals how black women experienced constructions of their sexuality and gender in relation to white women. The main questions guiding this work were: how did black women negotiate physical and sexual violence, colonial power, and female slaveowners in the eighteenth century, and how was freedom defined and what did freedom look like in a slave society?

Addressing the above questions, Fuentes describes and interrogates archival silences, and then works with these seemingly useless sources to reimagine black women’s experiences, filling in historical gaps in studies of early American slavery. For example, in her strongest chapter, Fuentes works with runaway slave advertisements to narrate the experiences of an enslaved runaway named Jane, as she navigates the colonial-built environments of urban areas that were constructed to terrorize fugitive bodies. Fuentes combines other sources to depict the architectural layout of the city that Jane would have encountered in her journey, such as the Cage (a place that held runaway slaves) and the execution gallows. In doing so, she demonstrates how colonial powers designed urban areas to confine and control black people’s movement.

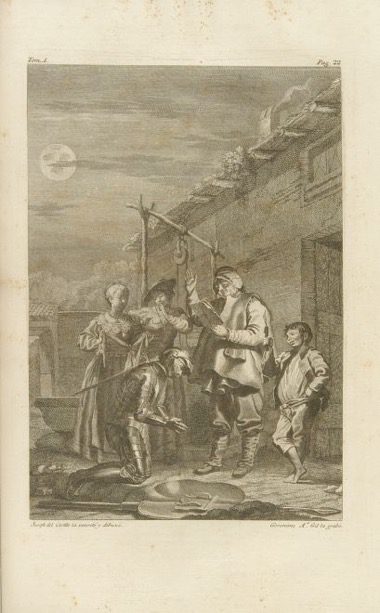

In another chapter, Fuentes explores how black women’s sexuality was constructed in relation to white women’s identity. In this section, Fuentes discusses the sexual entanglement of a white woman, Agatha, and two white men. The mistress sent an enslaved boy, dressed as a woman to murder one of her sexual partners during the nighttime. Utilizing the trial records of the boy, Fuentes demonstrates what the boy’s attire reveals about black women’s mobility at night. While elite white women were not allowed in public, unaccompanied, Fuentes argues that black women’s ability to cross urban spaces in the night suggests that society viewed black women as sexual agents and therefore as unwomanly. Dispossessed Lives demonstrates how white authorities positioned black womanhood in opposition to white femininity.

Fuentes further problematizes white and black people’s relationship in early America, allowing readers to fully grasp the nuanced meaning of freedom for black people. For instance, in her assessment of Rachael, a woman of color slaveowner, Fuentes challenges the dominant reading of Rachael’s agency in her active role in the commodification of black bodies. Fuentes does not refute Rachael’s agency itself but contends that Rachael was also subjugated to different forms of inequality due to the racial and gendered hierarchies within a colonial context. By questioning Rachael’s actions, Fuentes illuminates black women’s limited opportunities in the slavery era. Readers benefit from Fuentes’ take on freedom because she accounts for enslaved and freed people’s contradictory beliefs and actions.

Fuentes is a beautiful writer, and she responsibly narrates the different types of violence black women faced historically and still face (if we are not careful) through archiving practices and writing today. She intentionally acknowledges her own subjectivity in the work, and readers would appreciate this honesty from a scholar who is passionately concerned with the ethics of history and not reproducing the same historical violence. Dispossessed Lives is a must-read for all historians (professional or amateur), and I highly recommend this book for anyone interested in the possibilities for studying subaltern voices and the nuances of historical subjects and events.

Other Articles By Tiana Wilson:

Monroe by Lisa B. Thompson (2018)

King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop by Harvard Sitkoff (2009)

You Might Also Like:

Slavery World Wide: Collected Works from Not Even Past