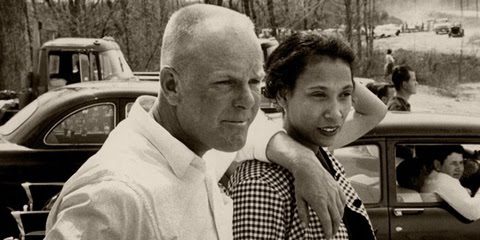

On March 23, 2017, the Institute for Historical Studies sponsored a roundtable on the landmark Supreme Court decision that struck down laws banning inter-racial marriage. Director of HIS, Seth Garfield, introduced the three panelists, who included Jacqueline Jones, Chair of the UT Austin History Department and well known to readers of Not Even Past, Kevin Noble Maillard, Professor of Law at Syracuse University and co-editor of Loving v. Virginia in a Post-Racial World: Rethinking Race, Sex, and Marriage, and Jeff Nichols, the director and screen writer of Loving, the 2016 feature film devoted to telling the story of Richard and Mildred Loving and their road to the Surpeme Court.

You can listen to an audio of the roundtable here. A transcript appears below.

Transcription by Rebecca Johnston, Henry Wiencek, and Maria Hammack.

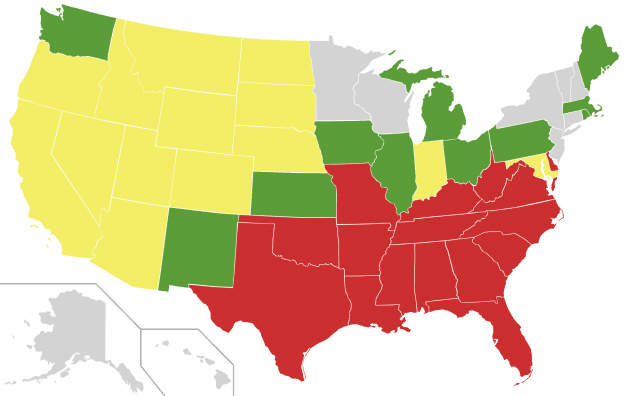

GARFIELD: On behalf of the Institute for Historical Studies it is my pleasure to welcome you this afternoon to our panel commemorating the fiftieth anniversary the Loving v. Virginia decision. This landmark decision struck down laws banning interracial marriage as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th amendment. At the time so-called anti-miscegenation laws were on the books in 16 southern states including Texas. Many years ago sociologist C. Wright Mills observed that “No social study that does not come back to the problems of biography, of history, and of their intersections within a society has completed its intellectual journey.” The story of Mildred and Richard Loving and the watershed case that bears their name in many ways epitomizes such intersections. A story of love, on one hand, so tender, so private, and so ordinary, and on the other hand to persecuted, so public, and so extraordinary, as the couples’ marriage became engulfed by and deepened the broader political struggles for Civil Rights and racial equality in the South. So today, fifty years after the Loving decision, we’re pleased to have an interdisciplinary panel composed of an historian, a legal scholar, and a filmmaker, to examine the historical origins of said anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, the battles to overturn them and the paths and challenges to greater colorblindness and marriage equality in the U.S.

GARFIELD: Our first panelist is Dr. Jacqueline Jones, Chair of the History Department and Walter Prescott Webb Chair in History and Ideas/Mastin Gentry White Professor of Southern History at UT Austin. Professor Jones is the author of ten books, including A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama’s America, published in 2013, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She’s also the author of Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work and the Family from Slavery to the Present, which was also a finalist for the Pulitzer, and won the Bancroft Prize. Her current project is a full-length biography of Lucy Parsons, orator and labor agitator, who was born to an enslaved woman in Virginia in 1851. Professor Jones has won numerous grants and awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Jacqueline Jones.

JONES: Thanks for the introduction, Seth. It’s really a pleasure to be here today, especially with my fellow panelists, Professor Maillard and Mr. Nichols, both of whom have done so much to advance our understanding of and appreciation for the Loving v. the State of Virginia decision: Professor Maillard through his wide-ranging book, Loving v. Virginia in a Post-Racial World, and Mr. Nichols, through the beautiful, compelling movie, Loving.

My first awareness of laws against intermarriage stems from my days as a high school student in Delaware, when I learned that my French teacher, my junior year, was not allowed to live with his wife in the state of Delaware. They lived in Pennsylvania just across the line instead. So among those sixteen southern states that banned interracial marriage through the 1960s was the State of Delaware. I grew up in a rigidly segregated little town of 500 people. There were four churches in this little town – two black, two white, three Methodist, one Presbyterian. This was a small town between Newark and Bloomington, Delaware. And if I’d learned anything from that experience, it was how presumably well-meaning white people could accommodate themselves to – acquiesce in – forms of discrimination such as anti-miscegenation laws, so-called. My parents and my extended family saw this as customary, as a matter of tradition, something that really did not affect them or other churchgoers at this time. So a reminder, here, as we look back to 1967 and wonder how people could so persecute a couple for their relationship, we have to remember how many people were indifferent, and some of course were actively outraged.

By way of introduction, I would just like to restate what Seth already mentioned in his introduction – the obvious central paradox that informs our understanding of the institution of marriage, that it is built on the most private, intimate of human relationships, and yet it is not only highly public, but also highly politicized. Specifically in the South, but not only in the South, the states’ regulation of interracial marriage has been a means to further and preserve white supremacy.

I’d like to very briefly discuss four themes today. First of all, I want to distinguish between interracial sex and interracial marriage. They are related, but they’re not the same thing. Secondly, I want to remind us to remain alert to the hypocrisy and dissembling. We’ll hear much about white men who objected to race mixing and miscegenation, but that is only partially true. Let’s see what they do and not just what they say. Certainly, there were distinct limits to their outrage. Third, the subject of interracial marriage has a history. We can compare, for instance, the Antebellum period in American history to the period after the Civil War and see how attitudes towards relationships, especially marriages between white men and black women, changed over time. And finally, I want to suggest that interracial marriage is a complicated question, revealing of definitions of family, race, power, and citizenship.

Those of you who know me and know my work know that I object to the word “race” for its imprecision, but mainly because it doesn’t really exist. It’s a fiction. Racial ideologies of course are very powerful, and have had a pernicious influence on this country. But that’s very different from the idea of race, which presupposes a hierarchy of racial groups and the notion itself of course seeks to categorize people into certain groups. I’ll be using the term race, though, even though I don’t think it really exists, except as an ideology, a political strategy. And the strategy here is among people who seem to construct hierarchies of power based on lineage and gender, and skin, color, and class.

So, here, at the beginning of my first point, which is distinguishing between interracial sex and interracial marriage, let’s go back to the 17th-century Chesapeake, Maryland and Virginia, those colonies, and reflect on the reality of colonial settlements, which had too much land and too few workers. We see, early in the century, masters of indentured servants, white and black, impregnating their women servants in order to extent those servants’ indentures. That is, in order to extend their time of service. It was illegal for a young woman who was a servant to become pregnant. She could be forced to serve more than the customary seven years if she did become pregnant. So what happened was officials in the Chesapeake began to pass laws saying that if an indentured servant became pregnant, her time would be given or sold to another master. That was to discourage masters from impregnating their servants and making them spend longer on their indentures.

Also during this period we find a very distinct development, and that is the colonies decide that legal status should flow from the mother’s status, and not from the father’s status. That was primarily because slave owners, again, were impregnating enslaved women. As a result, regardless of the father’s status, regardless of the physical appearance of the children, the children were, of course, legally enslaved. And I think this fact shows the “why?” of race. People often talk about race-based slavery. But in fact, children with one white parent or one black parent were of neither race. It’s very difficult to speak in racial terms of children whose parents are mixed. But in any case, we do find, throughout the Antebellum South, by the late Antebellum period, clear evidence that many children of slave owners have become enslaved, because they are the offspring of white men physically and sexually abusing enslaved women.

The term miscegenation was actually coined during the American Civil War, and the aim here of laws against miscegenation was to uphold the authority of well-to-do white men who sought to control land, labor, and inheritances to the detriment of white women. And also the detriment of black and Native American men and women. Before the Civil War, black-white marriages were not encouraged, certainly, but they were in many cases tolerated, because they didn’t threaten the racial hierarchies embedded in the institution of slavery. But beginning in the 1860s and then through the 1960s, the American legal code enshrined the idea that interracial marriage was unnatural. In other words, once slavery was destroyed, local and state officials felt they had to carefully monitor not just interracial marriage, but also interracial sex, mainly between black men and white women. We see in the 1890s, when the Populist Party is beginning to make a strong pitch for the common interests among black and white sharecroppers and tenants, we see during this period the demonization of black men, the image of the black man as rapist, the white woman as victim. This, as Ida B. Wells-Barnett and other anti-lynching activists pointed out, was a total fiction. And yet, it was an image that was meant to drive a wedge between landless black and white tillers of the soil who otherwise would’ve understood that they had much in common.

I want just for a moment, though, to detour to a marriage that I know a little bit about, and that is between a formerly enslaved woman and a white man. I just finished a biography of Lucy Parsons, who was born to an enslaved woman in Virginia in 1851 and forcibly removed with the rest of her master’s plantation to Texas in 1863, in the middle of the Civil War. After freedom, she and her family moved to Waco, where she met a young white man named Albert Parsons. Albert Parsons later became famous for his role in the Haymarket affair. He was hanged in 1887. In any case, Lucy and Albert Parsons were able to marry in Texas in 1872. And it’s interesting because there was a very small window of opportunity for them to do so. After the war, Southern whites were interpreting marriage laws to mean that black people could marry among themselves for the first time legally, but that they could not marry white people. In 1872, and for a few months in 1873, the Republican Party held sway in the State of Texas. Albert Parsons, who was a Republican operative, took advantage of that window of opportunity. He and Lucy got married; I think probably the mayor of Waco presided over their marriage. But by the next year, the Democrats had regained control of the state again, and the couple had to move to Chicago, where they lived the rest of their lives. She lived until 1942. They lived in a German immigrant community in Chicago, which seemed to accept them for who they were.

Bans on interracial marriage obviously have had implications for family relations. White kin have been determined to withhold from Indian, Native American, African American, and Asian would-be wives’ land, inheritance, and other resources from their marriage with white men. And this was, of course, as Professor Maillard has pointed out in his book, not just a black-white issue, but an issue related to a whole host of other groups defined as non-white. The point here is that a white man’s marriage to a black [woman], of course, implicitly implied a redistribution of land and resources if he died before she did. And that, of course, was something that white supremacists could not abide. Extralegal interracial families were common throughout the South after the Civil War. I would think that, had Richard Loving been wealthy, and had he not married Mildred Jeter, Caroline County officials would have left the couple alone. So we see a couple of issues there – the arrogance of white men of means in exploiting black women, and we also see the idea that marriage here really changes the dynamic, because it does involve control over land and inheritances.

So, the theme of hypocrisy. In the film, the county sheriff – I think it’s the sheriff, i’m not sure – says that that robins and sparrows were made separate by god, and that they should never be joined together. The judge, the local judge in the case, Bazile, rails against race mixing as if there is a real principle here at stake. We know, though, slave owners who raped enslaved women – that was a logical component of the slave system. By doing so and producing children, these white men enhanced their labor forces. Yes, they did enslave their own children. In the process, they also demeaned and humiliated black men, and they held the enslaved community in subjection. Mary Boykin Chesnut, the well-to-do wife of a South Carolina politician, said famously: “White women on the plantation seemed to know where the white children on other plantations came from, but the ones on their own plantation, they think dropped from the sky.”

So after the Civil War, black men’s sexual relations with white women became a piece with agitation for civil rights. Poor women who married black men were deemed immoral and promiscuous. But getting back to this hypocrisy about a time where segregation was certainly the law of a particular region, if not the land, consider the case of Strom Thurmond, who loudly denounced integration. If you’ll recall, Strom Thurmond, born in 1902 in South Carolina, was a U.S. senator for 48 years from that state. He ran on the Dixiecrat ticket in 1948, ran for president. In 1964, he became a Republican because of his opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, outlawing discrimination in housing and in jobs. That year – he had declared, actually, in 1948, when he ran for president: “All the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the army cannot force the negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement.” Well, note that many black women were already going into white homes every day to work as domestic servants, and as laundresses and as cooks. That was not the purpose of segregation, to keep black women from serving white households. It was to humiliate black people in public and keep them in separate parks or away from parks, in separate parts of the movie theater, and so forth. In 1925, Strom Thurmond raped a domestic servant in his house, 16-year-old domestic Carrie Butler. His daughter Essie Mae Washington and Thurmond’s family kept this secret until his death in 2003. Miscegenation laws were finally taken off the books in South Carolina in 1998 and in Alabama in 2000.

But what I wanted to juxtapose here was Thurmond, with his strident arguments against integration, when every day this vulnerable young woman was coming into his home, the home of his parents, and he certainly had no compunction about sexually abusing her. The Lovings, as people will recall, were sentenced to one year in prison for violating Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924. That year, I think, has a broader context. Obviously, it was a time when the United States was limiting the immigrants who could come into this country to those from European nations. It was a time of scientific racism. And under the Virginia law, members of so-called non-white races could marry each other, but they could not marry white people. So again, the aim here was to uphold white supremacy and not the separation of the races per se.

The relationship between marriage and power – this is clear, I think. And again, we come back to the fact that when Richard Loving did predecease his wife, his assets went to her. They, in other words, went presumably to her extended family within a black community. Their children were called unnatural and bastards, and again, think of the hypocrisy here. The United States has ample evidence that prohibitions against race mixing have not been adhered to at all. What is race – the Loving children, Donald, Sydney, and Peggy, were labeled black. But the mixed heritage here – Mildred Jeter was a descendant of Native Americans as well as of people of African descent – the mixed heritage revealed how foolish these very rigid, strict classifications were. So marriage is an integral component of American citizenship. It confirms not only rights, but also respect on a couple.

In conclusion, I just want to say that beginning in the British North American colonies and stretching into our own time, state-based efforts to control or prohibit interracial marriage and interracial sex, all the while sanctioning the abuse of black and other minority women – that’s a long and sordid history. Indeed, today we see vocal resistance to gay marriage among people who, like their Southern white forebearers before them, invoke god to argue that same-sex relationships, and not just marriage, are sinful. Obviously, we cannot congratulate ourselves that the Loving decision of 1967 settled this question once and for all. Though we can acknowledge that it was a long past due, if not entirely successful effort, to curtail state power in criminalizing intimate relationships in general, and marriage in particular, between consenting adults. Thank you.

GARFIELD: Thank you. Our next speaker is Dr. Kevin Noble Maillard. He is Professor of Law at Syracuse University. Professor Maillard is a co-editor of Loving v. Virginia in a Post-Racial World: Rethinking Race, Sex, and Marriage, published by Cambridge University Press in 2012. Katherine M. Frank, Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, noted that the edited volume “contains some of the most thoughtful, and original essays on race, family, nation and law.” Originally from Oklahoma, he is a member of the Seminole Nation, Mekusukey Band. He received his B.A. in Public Policy from Duke University, his J.D. from Penn Law School, and his Ph.D. in political philosophy from the University of Michigan. Dr. Maillard is a frequent commentator on race in the United States. He’s written for The Atlantic and provides on-air legal commentary to MSNBC, and is a contributing editor to The New York Times. We’re so pleased he could join us today coming in from New York. Please welcome Professor Maillard.

MAILLARD: Thanks for coming, I’m glad to be in such esteemed company here in Texas. This is really great and the weather of course is just really welcome for me coming from New York where there’s still snow on the ground.

I first became interested in this topic just by being born. My dad is West Indian, his grandparents came over from St. Maarten in the 1800s. My mother is from Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and that’s where I grew up. And so, I also went to high school in Tulsa, OK, where I had these parents with this background and then I went to an all-white high school so I’ve always kind of suffered being the only one of whatever it is in all of my institutions.

So, here’s what I find so interesting about licenses. We have to have a lot of licenses, do a lot of things. We need a license to drive. We need a license to in Texas to hunt, to own a gun. We need a license to do a lot of things. We also need a license traditionally to have sex. That’s what marriage is. When I tell this to my students they kind of look at me like “we don’t have to have a license.” But when the state is recognizing that relationship and according benefits, protections and privileges because of that relationship then the license to have sex becomes something that is worthy of holding and it becomes a property interest where we can exclude other people and we can have expectations on what we desire to get out of the marriage. We have this interest in marriage where we expect things to come from it. So, when we see these wars over what marriage means over who can and cannot get married these are just culture wars with marriage there that’s in the middle. That thing that academics on college campuses would call a liminal space. Normal people might call it a flashpoint. Other people on the street might just call it a really important issue. For marriage itself, it is a legal relationship but it’s not about love that much. Love is a new concept in the issue of marriage.

So, I study legal history and when we think about marriage this is an exchange of property. As Professor Jones was saying, we are transferring property from white men to other people. Would they have looked at the Lovings differently had Richard Loving been a rich guy? If he had a lot of property to give a way? If he had a lot of property to transmit at his death? Think of marriage also as a way of classifying people. Think of when you go to the doctor’s office and every time you go there’s some status that you have to put on. What do they want to know? Your address, your phone number, your next of kin, that kind of information. But they always want to know whether you’re married or not. That’s interesting, right? They want to know if you’re married or not and there are only four choices: single, married, widowed, divorced. Everyone else is just dead to the world. It doesn’t say if you’re dating, if you’re cohabiting, there’s no “it’s complicated” like they would have on Facebook. There are all these rigid statuses because the state can only see the red light or the green light, there’s nothing that’s in between. So, for marriage, it places people into pegs and society we can look at these people and say “are they joined? Are they committed? Are they not committed?”

So, from my own person life, I’ve been studying marriage and interracialism my entire career. I’m not married but I have my partner and we have kids together and then people then always want to know what our status is and I’m always really annoyingly academic and political about it. But then it’s the same thing as being married but I’ve always looked at marriage as a way to disenfranchise black people or differently as a way for the state to back away from people because once people are married the state expects them to take care of themselves. We could look at marriage as a way of privatizing welfare. In my home state of Oklahoma there are marriage promotion campaigns. “Why don’t we have these people all get married?” In one of the debates between Romney and Obama—this was the famous “binders full of women” debate—Romney said, well “why don’t we just have all these people get married” as if David’s Bridal is going to solve all our social pathologies.

We expect the state to rely on marriage as a way of saying: “once these people are married, they’ll take care of each other, they’ll be dual income or we hold that spouse liable for all that other person’s debts, their obligations, their responsibilities to society.” So, marriage itself is this golden circle of protection, of privileges, of expectations that has been used traditionally as relationship to either bring black people in but more so to exclude people of color from the franchise, to exclude people of color from full citizenship by saying “if we have these people who were once enslaved, let’s have them get married because then now all of these poor people can take care of each other, we no longer have any obligation toward these people.”

What about these people of different races that might want to marry? Now there will be a transfer of wealth, an intermingling of financial and property interests between these groups and there will no longer be any rigid boundaries between the different races and we will not be able to tell where one stops and the other starts. So, marriage is a function of the police power. It locates people within a society, it determines their status; it tells the state whether we can recognize these people as actually being joined to one another or not.

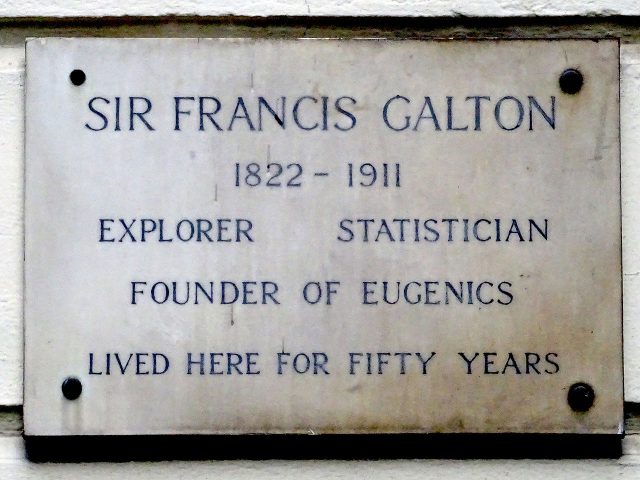

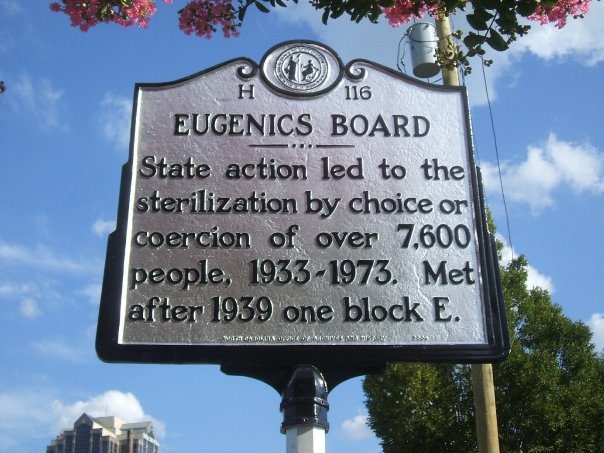

Here’s where it ends up being a legal issue about prohibitions and exclusions for marriage: Eugenics. Eugenics would be the science of human breeding. This was very popular in the early 20th-century. Eugenics— “we have the right people marry each other.” Without this policing of these people marrying each other, then our society might devolve. If we have careful examination of the appropriate people to marry, then our society will be stronger. What is this sounding like? At the forefront of this scholarship of Eugenics was a man by the name of Francis Galton who was English and was a half cousin of Charles Darwin and he coined the term Eugenics in 1883 as “the science of improvement of the human germplasm through better breeding.” Eugenicists vociferously argued that the white race as a superior group remained strong only when pure. They would have studies; there would be doctors that would back up these studies—not really good doctors; there were scholars that would write about this; there were state actors who would support this. What does this sound like? Fake science! It’s like history repeats itself over and over.

“A people that fails to preserve the purity of its racial blood, thereby destroys the unity of the soul of the nation and all its manifestations.” Who said that? Adolf Hitler. Adolf Hitler was part of the conversation of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The architects of that Integrity Act were three men by the name of Walter Plecker, Earnest Sevier Cox and John Powell. They led a campaign of racial politics in the state which classified miscegenation as “a breach in the dyke” to be stopped. They insisted on the legitimacy of Eugenics, which they defined as the science of improving stock, whether human or animal. The trio presented a racial apocalypse attributed to imprudent choices of sexual partners. Eugenics minded propaganda published by the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics warned young men and women considering marriage—the greatest and most important of human relations—and also lawmakers who were responsible for the future of the state and welfare of the race.

By presenting this future of the white race as dependent on individual, personal choice— “when you walk out on the street today, you’re making associations with different people, you might marry that person, you might have a child with that person”—the personal literally is political. These Virginians attempted to ignite a race panic that would soon be ingrained in law.

“The law is the witness and external deposit of our moral life.” this is written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Supreme Court Justice, in the Harvard Law Review in 1897. This statement conceptualizes law as a system of beliefs, a reflection of what our society holds most valuable—what it holds to be proper, how we should associate, who we should be close to. These are the components of the Racial Integrity Act—what our society deems to be most important. First, the act required all citizens within the state born after June 14, 1912 to register their racial composition with the Bureau of Vital Statistics, with Walter Plecker as director.

Secondly, the race registration certificates determined a valid marriage, thus preventing any non-whites from illegally marrying whites. Thirdly, the act defined a white person as one whose blood is entirely white, having no known demonstrable or ascertainable mixture of blood of another race, which they had to amend because some of the people that were white in the state of Virginia that thought of themselves as white that were part of the state legislature would suddenly not be counted as white anymore, this would have affected about 16 members of the legislature. So, they put a little bit of an exception in there to make room for people who would proudly call themselves descendants of Pocahontas. So, people who in Virginia would like to say “I’m from the first families of Virginia, the oldest families of Virginia” most of those people could trace their ancestry back to a non-white Disney princess known as Pocahontas—they wouldn’t be able to do that anymore. These people who wanted to claim that minuscule ancestry were no longer be declared white even if it was 1/156th part Native. These people would no longer be part of the white franchise in the state of Virginia.

We end up with Loving v. Virginia, where the Lovings are challenging this Racial Integrity Act of 1924 that was the intellectual commerce of Nazi Germany. What is a white person? the state invokes equal protection. they’re saying that everyone is being treated equally by this racial integrity act, because the law would be applied equally to whites and non-whites. Just like with same sex marriage, the laws banning same sex marriage would apply equally of people of the same sex who wanted to marry and other people—it didn’t single out anyone, these different state laws would say, this is just the way the law is.

The state also said that the court should defer to the wisdom of the state legislature. For me as a family law professor, this is usually the explanation of courts when they don’t really know what else to say—and especially when the claim they’re making is generally unconstitutional: “let’s leave it up to a popular vote.” Here’s what the supreme court said in Loving v. Virginia: “there is patently no overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which would justify this classification.” So, we have two constitutional issues in the 14th amendment that are at play here: one would be an equality issue—black people, native people, Asians, Latinos would all be able to marry each other in this Racial Integrity Act. why? Because the Racial Integrity Act was only about white racial purity. So, a family like mine, they’d say “marry each other all you want, we don’t care about blacks and natives. all we care about is if there is a white person involved.” That is what racial integrity means.

There is also the liberty issue. The fundamental substantive due process issue which is just a legal way of saying this is a fundamental right for people to have the choice of who they want to marry. The state should not be involved in that decision. Why should we defer to the state legislature when it comes to fundamental rights? Would any restrictions on marriage be constitutional? You would have someone in most recent history like Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice, who would have said “do all of these laws mean the end of all morals legislation? If we allow for the striking down of sodomy laws, does this mean that one day bestiality will become legal? Everyone can go and marry their mothers? We can have marriages with plants and animals? We can marry our dog? We have to have some line somewhere. We cannot decide this based on an idea of dignity—that’s not an appropriate road. What we do have to think about is tradition, this is the way that states have always looked at marriage, which has not always given every single autonomy the ability to make that personal choice to the individual actors.”

Let’s go a little ahead to today with marriage equality. Obergefell v. Hodges most recently deemed that marriage between same sex partners is now legal across the land. It’s like an opinion justice Kennedy was just waiting to write: the first thing he cited was Loving. Couldn’t even get off the first page without mentioning Loving v. Virginia. Why? Because there are the same constitutional ideals of equality—are similarly situated people being treated the same? —and we also have the fundamental rights issue of marriage, making these private decisions about who they want to spend their life with and have it recognized by the state. These people they would transpose these same ideals from Loving to the same sex marriage context, so then when we have Justice Kennedy writing this opinion it’s like the first thing that he can say is this is exactly like Loving. Then he goes off into this long soliloquy about “if people cannot get married then they will be lonely forever and we don’t want people to get lonely and we want children to be protected by their parents, we want to have dignity for all these different groups.”

The reasons why marriage is a fundamental right become more clear and compelling from a full awareness and understanding of the hurt that results from laws banning interracial unions, and then also same sex unions. So when Scalia and Thomas say “let’s rely on state legislatures for these laws, we do not need to engineer from the bench, we do not want to be judicial activists,” I always say to my students: are we part of social engineering already? Are we the results of this? If those laws had not been in place now, would there be more people in the United States that would openly declare themselves to be gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual? Would there be more people in the United States that would declare themselves to be multi-racial? Would there be more opportunities for people to be multi-racial? Because then when you look around the room maybe about 1/10 people might be of 2 different races. Is that a personal choice that someone was making, that someone’s grandfather was making, that someone’s grandmother was making? Yet here we are today still with a majority of people being of one race. Had those distinctions not been made so apparent and so illegal would we have a different nation now? Would we look like Hawaii? Would we would look like Mexico? Would we look like Brazil?

Can we ask what the role of law is in our everyday lives and the decisions that other people will make in our past that brought us here—how does that affect the way that we represent ourselves, and the way we see our current world? As I started off saying, the law is the witness and external deposit of our moral life, written by Oliver Wendell Holmes. We could say that interracial love is complicated, it’s unacknowledged, it’s part of our American past. The result of this is that integration at the most intimate level still continues to be a bit of a taboo. It’s the duty of scholarship, of art, of film, of all of us here to fulfill of all those voids in that story of American history.

GARFIELD: Thank you. Jeff Nichols, the Director and Screen Writer of Loving, has been held by acclaimed critic Peter Travers as ranking with the best American directors of his generation. After graduating from the University of North Carolina School of the Arts School of Filmmaking, Mr. Nichols went on to write and direct several internationally acclaimed features including Shotgun Stories, which received the Grand Jury Prize at the Seattle and Austin Film Festivals, and the International Jury Prize at the Venice International Film Festival. Take Shelter, which received multiple honors at the Cannes International Film Festival, including the Critics Week Grand Prize, and was later nominated for five Independent Spirit Awards. And Mud, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, was also a Spirit Award nominee. Loving was released in November 2016 to widespread critical acclaim. It was dubbed by the Hollywood Reporter at “the most relevant film this election season.” Of course, anyone who’s seen the film knows this as well. It’s insistence on the power of love to stand-up to bigotry and injustice is narrated with astounding restraint and poignancy, by a filmmaker at the top of his game. Please welcome Jeff Nichols.

NICHOLS: Okay. I am definitely out of my league with these people. So, a few caveats to start, much like our president, anything that comes out of my mouth should be fact-checked, because I make movies, and I am not a professor. I thought about why I was here, and what I should talk about. And as narrow as I could possibly get I thought I should talk about the interpretation of history. Chiefly my interpretation of history.

This is the fifth film I’ve made and it’s the first one not cut from bulk creative cloth. There is a strict responsibility that comes with that. The first person I met when I started to do research on Loving was Peggy Loving, and when you sit down with the relative of this person that you are about to put on screen, you are immediately struck by how important the task you have is.

I was struck by that. But even with that, what you are seeing when you watch Loving is my interpretation of something. And that’s good and that’s bad. I tried as best as I could to adhere to the facts that I had accessible. And, at the same time I was making a point. You can’t help but make your own point through this stuff. I think it’s an important thing especially for people in an institution like this is to understand that every book you read, every film you see, is somebody’s point of view of history.

I’m 38 years old. I was born in a working middle class suburb in Little Rock, Arkansas. I have an interesting point of view on what I thought the late the 50’s and 60’s would be like. I thought a lot about, as a guy who has dedicated his life to writing screen plays, that talk about the southern experience. I thought a lot about what a southern audience would think of when they saw Loving.

And oddly enough, spending the last four months on an insane literal campaign to try and win an Academy Award I’ve been bouncing back and forth between New York and Los Angeles, in very comfortable rooms, very liberal rooms. And I was thinking about what the middle of the country would think when they saw this film. A good friend of mine, who was a minister of mine when I was growing up, I remember talking to him. He’s always been a fan of my films and I said I’m making Loving. He said “oh that’s great Jeff, that’s an important story, you should tell that story.” I said: “Well yeah, you know it has all this relevance to race, but also to marriage equality as well.” And he’s like: “Well hold on, that’s different, the Bible tells us about that.” And here’s a man who I truly respect, and I grew up listening to, and taking a lot from. And yet he is of a generation and place that can’t wrap his mind around the validity of gay marriage. That’s who I wanted to go see this movie.

And if you’re going to do that I think you start to craft a movie in a certain way. I did not ever want the film to speak down to people. If you use this person as an example he’s an extraordinarily intelligent guy. I never wanted to preach at him. I never wanted to make him feel like he was stupid. Chiefly because I don’t think the Lovings would want that. So you end up getting a film that has a really distinct point of view and there are pros and cons to it. But it’s a point of view I was really trying to show. It is the humanity of these two people.

I was trying to make it so that by the end of the film what you’ve seen is undeniable, its unimpeachable, the way that these two people felt about each other. And in doing so hopefully I’m also not betraying who Richard and Mildred Loving were, as far as I could tell. And there’s one big point that I had to accept, that I had to go, that I had to believe to this day, and that’s the idea that Richard and Mildred Loving fell in love sincerely, genuinely, not as a reaction to the environment around them.

And this is really the point when you think about this approach that I’m talking about. They were not two young kids who were rebelling. They were not two young kids whose parents said you will not marry that white man, you will not marry that black girl. Because, and the reason why I think that’s so important, is they genuinely loved each other. They genuinely fell in love with one another. And when that is the basis of this story I feel like your arguments start to run out of fuel. And, in order for that to happen, though, they had to be in a place that was extraordinarily unique in the Jim Crow south.

Luckily, it is my opinion that they lived in such a place. Central Point Virginia was not really even a town. Bowling Green, which was the county, see, that was the town. That’s where the sheriff came from that arrested them. That’s where the judge Bazile was that wrote the opinion that helped it get to the Supreme Court, or not the opinion, but the township of Central Point though was extremely poor, very agriculturally based and there had been a legacy of racial mingling there for decades. Mildred Loving said it at the beginning of Nancy Buirski’s documentary the Lovings’s story which was the foundation of my research, “people had been mixing for a long time we just didn’t think nothing of it”.

That’s a dramatic statement to hear from a woman in 1965 because its true to her point of view. There’s a fact that is pointed out in the film through a mildly clunky monolog written for the sheriff, where he points out that Richard Loving’s father actually worked for a black man running timber. And if you think about the psychology of a white kid growing up in the 40’s and 50’s in Virginia, and his father’s livelihood, his family’s livelihood is given to him by a black entrepreneur. That starts to change things in your brain. He’s in a community where his friends, who he raced, drag-raced cars with, they were of mixed race. They were either Native American, black or white. There had been so much racial mingling there, that there really was a unique make up in this community. You can go there today, that’s where we shot the film, where we had open casting calls, the skin tones, the cheek bones, the people’s faces there are beautiful. It is a very unique bubble. And, so, it was integral to my interpretation of this whole thing, that, that bubble exists to a degree. Now a lot of people that watched the film they call BS. That’s fine. And everybody is entitled to their opinion and certainly there is a complexity on the ground of what was really happening there. There is no way that I could reach that in film.

But what was important to me, again, was that there was an environment where these two people, they could love each other for who they were. I believe it. I made a movie about it. And what I think that does is; It shows you two people that are living in spite of the laws, in spite of the social norms around them. And, it allows them, it allows you to make the argument in the film or ask the question what’s wrong with this? And I think everybody in this room knows the answer to that. That there is nothing wrong with that. So, that’s it. That’s about all I have for this. I just wanted to give you an idea of how I approached it. And I don’t know that’s all.

GARFIELD: And we have time now for some questions for the panelists.

AUDIENCE: Was there any attempt by the state to use religion as the justification for –

NICHOLS: Yeah, I mean, in the initial thing that Justice Bazile writes, which you should read, he starts off – God separated the races, therefore he did not intend for the races to mix. But that was out, bold, that wasn’t constitutional. Yeah, that was not – that was what was actually – Bernie Cohen and Phil Hirschkop, who were two lawyers who worked for the ACLU on behalf of the Lovings, I think they saw that as a wonderful gift when they read that from the original trial.

AUDIENCE: You mentioned in 1872, the legal marriage. What happened to legal marriages after miscegenation laws?

JONES: Well, that’s a really good question. And by the way, I should send Jeff a picture of Lucy Parsons. She looks like Ruth Negga, so she could play Lucy Parsons in the movie. But it’s a good question. The Parsons had to leave once the Democrats came into power. And as far as those other interracial marriages – first of all, I assume there were very few of them in that very limited window of a few months. But yes, I assume, you know, they would have been annulled or considered illicit relationships after the Democrats took power and interpreted the law differently.

AUDIENCE: I have a question for Mr. Nichols. I haven’t seen your other films, so I don’t know if this is a stylistic question or not. This is a really spare, minimalist film with very little dialogue and a lot of eye movement and looking at each other, not looking at people. I’m wondering what went into that choice.

NICHOLS: Yeah, and honestly, I think I got flustered and stopped talking to [inaudible]. There is another big factor in terms of my interpretation of this stuff, which is that this is the fifth film in my filmmaking career. And there are a lot of decisions that come into play, just in terms of my development as a filmmaker. I think Loving, out of the five films – they’re all my children, so I’m not going to say it’s my favorite, but it is certainly the most precise in terms of its execution. Number one, I finally had enough money to have enough days to execute everything in the script. The film I had made before that was a sci-fi film, and I didn’t know half the time what I was doing. Which is usually the way I feel on the set. That wasn’t the case for Loving. Now that being said, a big source for the way that they were portrayed in the film was archival footage that Phil Hirschkop helped Nancy Buirski, documentary filmmaker, unearth in the late 2000s when she was making a documentary. Hope Ryden was a documentary filmmaker that went down to Virginia at least two times, possibly three or four, and she had this beautiful black and white archival footage of the Lovings in their home. That combined with Grey Villet’s photographs from Life magazine is really where I started building their nature, who I thought they were. I spoke to Peggy, I spoke to Bill and Bernie, but it was really through that footage that you really realize – she is eloquent and graceful, while also completely earthy and of this place. He’s terrified. He, when a camera is put on him, just withers; he can’t handle it. I saw a lot of my own grandfather in him, in terms of that, and I thought about how difficult it would be for a man like that, who, a working-class, redneck Southern guy like my grandfather, to have to enunciate the love he felt for someone publicly. I think that would’ve been a crippling experience for my grandfather, and it looked that way for Richard Loving. So a lot of what I built was based on that interpretation. But it runs side by side with my evolution as a filmmaker, which is someone that hates expositional dialogue. That’s usually because – Kevin and I have spoken about this before – it’s usually because I’m writing fake characters in fake situations and I want to try to make them sound honest, and I want to try to make their behavior believable. and so usually I’m trying to listen to human behavior and human speech, and get it right. And a lot of times in films we have characters speak their backstories and speak their histories in ways that are completely dishonest to me, and it bothers me. So sometimes to a fault I’ve made my films and the dialogue in them redundant, and I’ve tried to make it just reflect the behavior that would happen in the moment. And make that kind of a cross I have to bear as a storyteller to try and make everything exist in two hours, in that format. So what you’re seeing is my interpretation of the Lovings, but also the evolution of me as a filmmaker.

AUDIENCE: In the article in Time Magazine, evidently Mildred Loving claimed never to be African American, she claimed she was Native American. And I’m just curious, is there a reason you didn’t kind of deal with that, or how did you – because in the movie it’s not really – it looks like, yeah, there’s mix, but it looks like their brothers and family are all African American.

NICHOLS: And they look like that today. And if you go speak to her grandson, who looks very much like that, he 100% claims to only be Native American, and actually took issue with the fact that the film would claim that she was African American. Which – the film really doesn’t – if you watch the film, it just doesn’t, it’s just not [inaudible]. Again, the monologue, by the sheriff, he mentions Cherokee and Rappahannock blood running around in all of those people, and then just being kind of mixed up, as he puts it. There is actually a certificate that was not her marriage certificate, where she actually put Native American, I think on her original arrest records she put “mixed race” and she put “black and Cherokee.” I’m not actually sure she was Cherokee. That might’ve just been what she thought Native American was, although there were Cherokees in that area, but mostly it was Rappahannock. You know, the film didn’t – I don’t know, the film – there was never a time to have him talk about it. It just didn’t seem like a conversation they were having. But the thing that I find fascinating about it is really just how elusive identity is, and how personal it is. It’s certainly not something I consciously didn’t want to talk about, because at the end of the day that’s the whole enchilada. The reason why – there are lots of reasons, one of the main reasons why the state’s case fell apart in the Supreme Court is because it was based on pseudo-science. It was based on the idea, if you read these anti-miscegenation laws, that if you show one drop of Negro blood. They were trying to – you could see them in the laws trying to wrangle scientific language to support their case. And it of course was ridiculous. But no, it’s a fair question. I can’t really answer it as a storyteller. I just – there wasn’t a place where they would sit down and be like, you know, I’m actually Native American. Like I just couldn’t hear Mildred saying it. So that’s probably why I didn’t show it.

MAILLARD: And I think there’s been exceptionalism accorded to intermingling with Native people as opposed to African people. Because just think of in your own personal life, people will readily, as I said when I was up there, will readily tell you that they have Native ancestry.

NICHOLS: I am 1/32 Cherokee.

MAILLARD: Yeah. But then like, nobody can tell me that – nobody will come up and be like I am 1/32 black. One out of one hundred people can do that. And that would even stem from Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson wrote: “Are the beautiful mixtures of red and white just so pleasing to the eye, not like the bileless mixture of white and black, which is more akin to an orangutan,” or something like that, right? So there’s always been – okay, it’s great to have Native and white mixed together, and people would claim that as maybe some way, some entire of equality with whites that would be treated differently than African equality with whites.

AUDIENCE: Were there other states that had the anti-miscegenation laws, and then their legislatures just by the normal process vacated those laws? Were there other court decisions, either from the Circuit or the Supreme Court that addressed them?

MAILLARD: Yeah, definitely, there was an earlier one in Virginia, there was one in California, Michigan had one at one time, and then it back. So at one time there were 41 states in the United Stances that had them since 1865 all at different times. And then strangely – some of them were really surprising. Like in South Carolina, they didn’t actually have one until after the Civil War. It was more based on – I think you mentioned a little bit – based on reputation than an actual blood thing. So someone could be very dark and look like me and just be considered a white person because they were rich. The same way like in Brazil, Pelé is considered white because – Pelé’s a soccer player – because he’s rich and not necessarily based on skin tone. So at one point in time, almost every state had it, but it was never all at the same time across the United States.

AUDIENCE: This year also marks the fiftieth anniversary of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? So I would like to get your sense about how you view how Hollywood has treated the evolution, how Hollywood has treated interracial couples, marriages, on film and get your feedback on some notable aspects of that.

MAILLARD: Well this is weird because I’m writing a commentary on the [New York] Times for that next month and that’s why we were talking about the Times. There’s actually – for Hollywood, there are a lot of movies that are out right now. Get Out, the horror movie, that is coming out next Friday. United Kingdom, which is kind of the Loving for Britain. So I think there’s always a fear of approaching this. One would be financial, because maybe they think that the film won’t sell, and I think you could speak to that a little bit more. But then always this – I think it’s a legacy of what we think of as personal and what represents us as a people. And then there’s a body of film with an absence of interracial families, which teaches us through its absence that this is not something that is normal. Because you can walk out on the street, you can walk out here on campus and it’s like, all these kids out there, mixed ancestry. But then you don’t see that on screen. And it’s almost as if these people are saying, I’m not seeing myself on screen, I’m not being represented. And this is teaching people your own existence, your own marriage, your own family is abnormal.

NICHOLS: I’ll try and answer this as honestly as I can. I’m not being politically correct, so excuse me. But I think – for one, as an example, Loving was the easiest film I’ve ever had get financed. There were multiple people that wanted to tell the story. There were some people who didn’t want Joel in the part, or didn’t know who Ruth was, and that is a totally different conversation. But I found multiple people that wanted to be a part of this. And now you can certainly add the success of a couple of my movies and where I was in my career; that helped, all of that helped. But I do think there was an appetite to have this story told very well. So set that aside, but that’s just truth, that happened. The thing is – talking about this is – I’m part of the problem. When you hear about Hollywood, I’m a white male writer and I’m the one, when I create fictional stories, that doesn’t create an interracial couple at the center of it just from scratch. And as I sit here and think about that, and think about being part of the solution and part of the problem, I do think that there might be something to this idea that sometimes either – one, you just don’t even think about it. And that’s a big issue. LIke, you’re just like, well, it didn’t occur to me to make those people interracial. But I think another part of it is – so I’ve made five films basically all in the South, and Loving is the first one that addresses race. And that is – there’s a reason for that. When I started making contemporary Southern fiction, and I had read a lot of Harry Crews, I read a lot of Larry Brown, obviously William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor. I wanted it to reflect things that I had seen out my door growing up in Arkansas. I knew if you take a film like Mud for instance, if I enter a black character into that film, I’m going to have to talk about it. It’s going to become – it’s not something that can just happen as a character in a vacuum, especially in Arkansas in the river in a community that is still extraordinarily segregated. So much so that when we were filming some high school sequences there, our producer’s like – I think we should really incorporate some black students into this. I said, I agree, and we did, and some of the white high school students that we brought in as extras gave them a hard time. So it’s not that it’s not a subject that I shy away from or don’t want to talk about, but it becomes the story a lot of times. And I think for a lot of writers, my self wholly included, sometimes we don’t know how to express it, how to talk about it, how to show it. Making Loving and being on this circuit, being the first feature film to screen at the African American History Museum in DC, has been extraordinary [inaudible] for me, but it’s also opened up my eyes up to my limited point of view. And I would like to think that I am now a storyteller on the other side of a point of view than I was before Loving. It is a complex issue, but I think that has something to do with it. I think interracial relationships specifically – and you all talk eloquently about this – I still think it’s something that’s difficult for Americans to talk about, because we don’t talk about sex very well. It’s why we don’t talk about marriage equality very well, either.

JONES: I just wanted to say, about 1967, that particular moment. People in my small town later used to say that the school I went to, grades one through eight, a very tiny school, that it was integrated peacefully because it wasn’t a high school. There was a lot of fear around the idea that integrating high schools mean kids would fall in love with each other, that kind of day to day interaction. And you do see that in some, you know, not only Central High in Little Rock, but other places around the country, that intense opposition to integration. The other thing is we have to remember the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which opened up workplaces to people of color for the first time, and made discrimination illegal. Various kinds, more and more housing was becoming integrated to a certain extent. And then in 1965, of course the Civil Rights Act related to voting. So it is a particular time when for the first time in history, I think, more Americans are encountering people who are different from themselves in the workplace, in school. And so yeah, 1967 I think is kind of a defining moment there.

NICHOLS: And also, when we put this trailer up on YouTube, Focus chose to close down the message section because of the vitriol. So it’s out there.

AUDIENCE: My question is for Mr. Nichols. I have two questions. I saw the movie about two months ago, I was really impressed with your work with the actors. You mention that your theme was love, and showing that they genuinely love each other, to me that seemed very real in the film. I’m curious how long were you working with Joel and Ruth, the rehearsing process, like how long did you work with them. And my second question is what exactly compelled you to make this film now.

NICHOLS: I don’t rehearse. And I introduced Joel and Ruth – I cast them kind of in a vacuum with one another, which seems a really stupid idea in hindsight. But they’re such great actors that they were able to not only build the character of Mildred and the character of Richard, they actually built the couple, which is where I think if they’re given any accolades, that’s what they need to be given accolades for. Because that’s hard to do. Especially when we got lunch together out in LA one time, like several months before we started filming, and then they should have gotten two weeks before we started filming. And we don’t rehearse, we just kind of hang out. I took them to all the real places and all the real locations, a lot of them are in the film, so they are just really great actors. What I’ll say about their behavior in the film is what I try to do on the page is set that behavior out, the way people cross through a room, the way they react to one another when they’re sitting closely to one another, if you take the first scene in the film as an example. I try and put that on the page, and then when you hire very intelligent actors, which I did in this case, they’re there with it. They understand it and it actually doesn’t take a lot of rehearsal in my experience. Other directors would disagree. There were a lot of reasons why I chose to do this back in 2012. I was flattered by the producers when they approached me, first off. I grew up in Little Rock and I attended Little Rock Central HIgh. I graduated in 1997; the desegregation crisis was in 1957. I was inundated with civil rights history as a result of this, and I didn’t know about Richard and Mildred Loving. I was ashamed of that back then and I was curious as to why more people didn’t know about them. Also, my best friend growing up was gay, and he is from Arkansas, and the man that he married is from Texas, and they got married outside of Syracuse. I was the best man at their wedding, and I realized neither one of them could get married in their home states. And that angered me. So I had – I was kind of pissed off. And also I saw Richard and Mildred’s story as set out in Nancy Buirski’s documentary, as this beautiful, beautiful way to cut through all of my anger. And to talk about humanity. Again, it seemed to disarm all of these points, just in its sincerity. And that is a – I just haven’t seen that a lot, especially something that I felt like was true.

AUDIENCE: I saw the movie, Jeff, and loved it. One thing I can tell you about it – my wife and I watched it late at night and did not fall asleep. I think it’s probably safe to say that most Americans get their history from movies, so, rather than from the scholarship that we write. Which seems to bring with it a special responsibility when you’re dealing with actual events. Now, I imagine that a lot of the dialogue we hear is made up. The reason I ask this in part is I was just on a panel with a film critic and I railed against movie after movie that depicted history and made stuff up. And the film critic looked at me and said, Michael, you’ve got it all wrong. If you want to learn facts, go read a book. If you want to feel something, go see a movie. And it struck me that this is a movie which really captures the feel of things, in a way that I think is extremely powerful and important. But I fear that most Americans who see this will stop right here, stop with the movie and never go beyond that. So did you feel that sense of responsibility and if you did, how did you cope with it?

NICHOLS: I felt less responsibility, you know, outward to an audience and more just to Richard and Mildred. There was actually a TV movie of this made on Showtime in the late 1990s, with Timothy Hutton. And it no longer exists mainly because Bernie Cohen was an advisor on that film, and Phil Hirschkop was not, and when the film came out, there was only one lawyer. And Phil is very good at suing people, and he made it so that that film does not exist. Yeah. But Mildred was alive to see it, and she said – about the only thing they got right were our names. And I didn’t want that. So I tried to adhere as close to fact as possible. A lot of the lines are taken directly out of their mouths from the documentary. I made up one big thing and I tried, though, to not make anything up that I couldn’t point to some fact. And this is more about the [inaudible], it’s not entirely striking the heart of your question. But there’s a very dramatic scene in the film where they sneak back into the county to give birth to their first child. That happened. And then they are subsequently rearrested. That happened. Those two things did not happen together. So that is my taking creative license. One to make kind of this first section of the film really laid down in a cohesive way. But also just to make it dramatic as hell. And heartbreaking. So that’s an example of, well okay I had this fact and I had this fact, I’m going to condense those two things and that’s the license that I’m giving myself. But through the whole thing, and the critic that you spoke to I think was – you’re right – I just wanted to get the essence of them and the essence of the story correct. But I’ve been shouted at at these things before for not fully understanding the tone and the situation of the Jim Crow South in this period. And the damage and the anger and the hurt that came from it, because I just made a movie that focused on love. So there are certainly people, and I think they are completely justified in a lot of ways, for saying that my point of view through the film is limited. And so at some point you just have to focus on the people who you’re trying to represent, try to get them right, and still try to make a movie that people will watch.

AUDIENCE: This is a little off topic. I’m with an organization here at UT, Events Entertainment, and one of our committees is Showtime, we put on films for the students. This is absolutely a film that we would love to bring to UT, so I was wondering if we could get your contact information.

NICHOLS: You betcha.

You may also like:

Slavery and Freedom in Savannah

Historical Perspectives on The Birth of a Nation (2016)

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.