Go to the supermarket, check out the food information detailing the nutritional facts, buy it, and take it home. These everyday actions define our connection with food and shape who we are as consumers. Through social media, we are constantly confronted with information that associates food with health, wellness, and organic products as an endless line connecting what we eat now and the consequences in our future. Yet these decisions are not just about individual actions. Rather, food, technology, marketing, and nutritional facts — and the networks that bind them — have their own history of institutional and social construction through the twentieth century.

It is this context that Xaq Frohlich, a historian of science, technology, and food, takes as a starting point for his book. As a result, From Label to Table presents the history of institutionalism around nutritional facts, the social construction of consumers, the changes around the perception of food and its marketing, and the search to make food scientific and objective in the United States during the twentieth century.

The book’s six chapters present the history behind the construction of nutrition facts, following the different stages of the Food and Drug Administration‘s (FDA’s) decision-making. Frohlich identifies three stages in the relationship between consumers and food: the era of adulteration (1880s to 1920s), the age of food standards (1930s to 1960s), and the era of information (1970s to the present). Each era witnessed distinct politics and marketing techniques (production, distribution, and consumption) as well as legal and scientific expertise that created a conception of the consumer and worked with consumer tactics. One of the book’s main contributions is that this periodization embraces a more extensive macro-historical process in the United States in the twentieth century, from food scarcity to overconsumption.

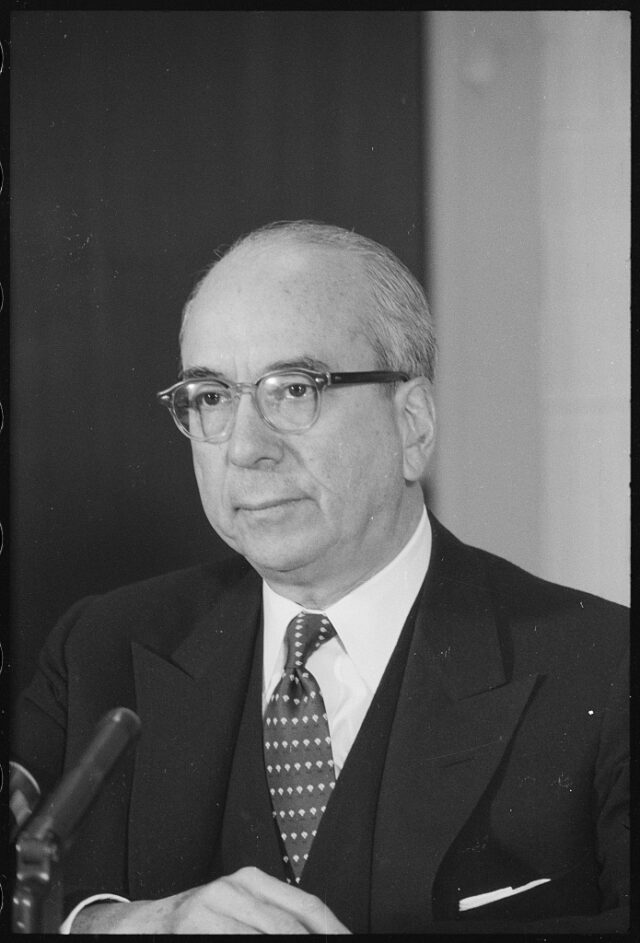

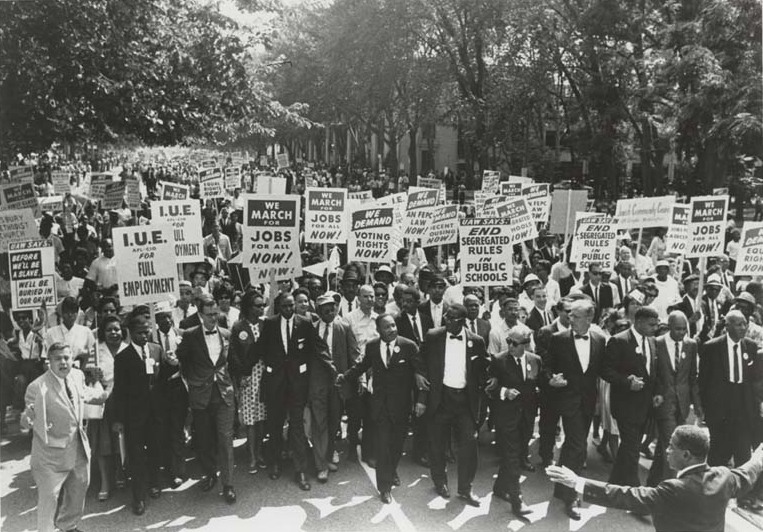

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

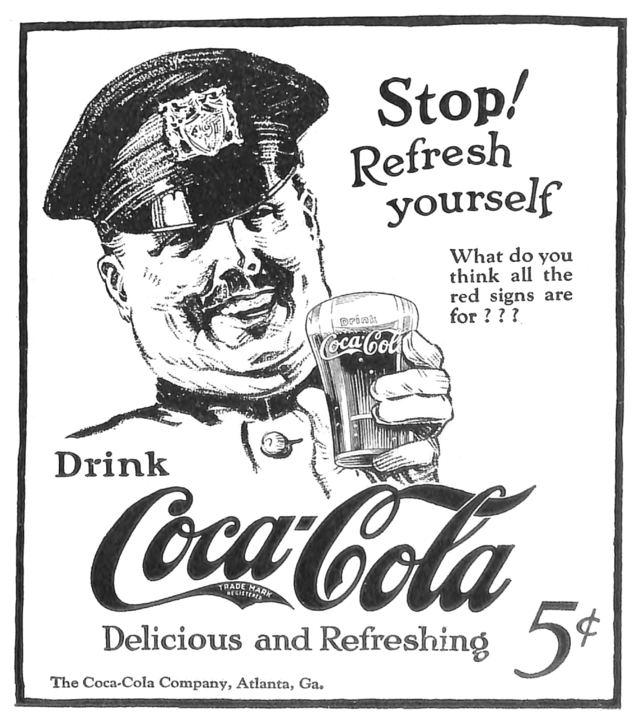

During the first decades of the twentieth century, urbanization and industrialization modified how people in the United States produced, consumed, and packaged food. Likewise, the development of global corporate entities, such as Coca-Cola, set the course towards a visual component through packaging and consumers’ feelings. Similarly, some companies produce food with vitamin-infused components. This process was modified through World War II, when food production accelerated via technology, specifically through long-term storage and heating infrastructures, such as refrigerators and microwaves. For the author, this global component encompasses decision-making around new food regulations in the United States.

Frohlich proposes two developments that changed the relationship between consumers and food in the decades following World War II. The first was the role of women as principal consumers. For the FDA and food production companies, women represented the new ideal food consumer, and they looked for new ways to persuade them to purchase their products. At the same time, food and science focused on medical debates such as using artificial sweeteners and their links to diabetes, cholesterol, and heart disease, increasing consumer information through what Frohlich calls nutritionism. At the same time, the expansion of supermarkets was a “self-service revolution,” increasing consumers’ independence in choosing food (p. 58-9). Both changes, Frohlich argues, pushed the state away from food regulations and contributed to increasing individual consumer choices and the role of private companies through nutritional labels.

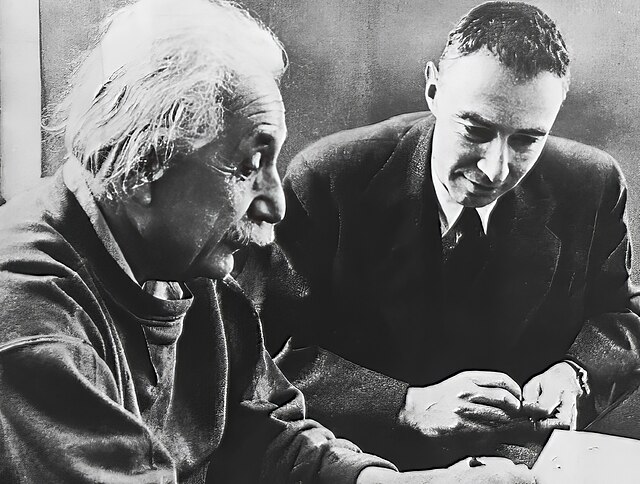

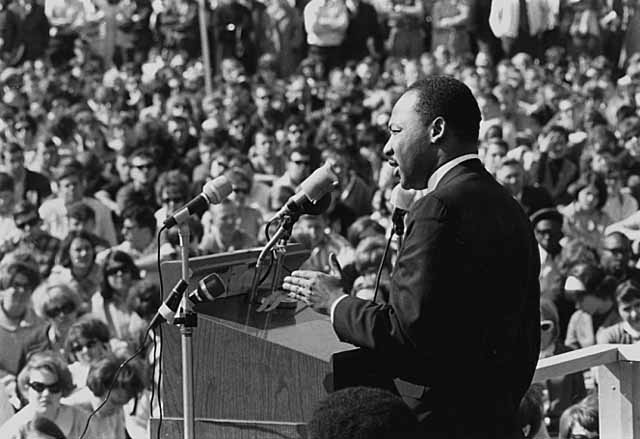

Source: Library of Congress.

This process increased exponentially between the 1970s and the 1990s. In the 1970s, the FDA sought to include food labels that would aid individual consumer research, which, united with the role of private food companies, moved the food and medical debates more and more into the private sector. In an increasingly neoliberal context, nutritional information mashed together science and numbers. For Frohlich, the connection between health and nutrition can also be traced to the first Earth Day in 1969. Here, the emergence of ecologism in the United States increased the connection between individual decisions about food and climate change. This awareness of food production is fundamental to understanding, for example, the introduction of the biotech industry in producing genetically modified foods in the 1990s and our present debates about organic products.

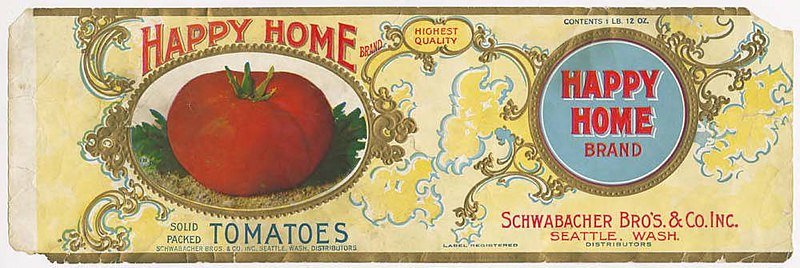

Another contribution of the book is the conception of nutrition facts as an everyday technology. On the one hand, Frohlich shows how nutrition facts are a technological infrastructure. During the twentieth century, the development of nutrition labels and facts created a specific language of nutrition, where food was related to science and, as a marketing technique, to health. Of central importance in this historical process is how this language was incorporated into everyday American life. Here, the author’s theoretical approach is practical not only for food studies but can also be incorporated into the history of everyday technology in a broad spectrum, considering the relationships of consumers –emotional, informational, and risk ties— with technology and vice versa.

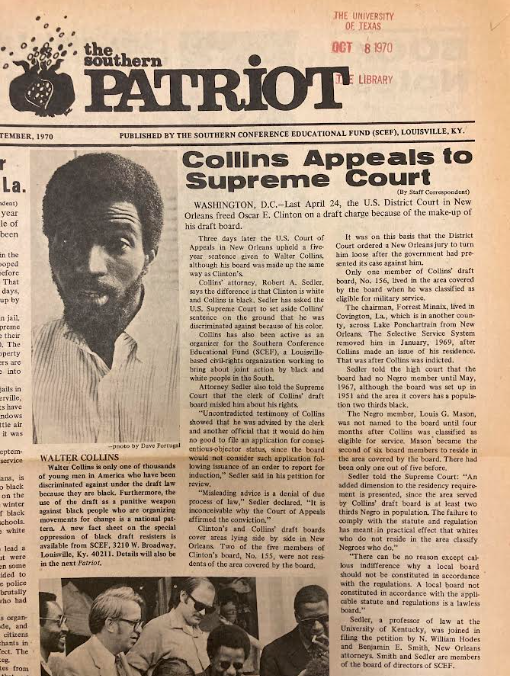

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On the other hand, for Frohlich, introducing a new language into the private sphere represents a singular vision from the United States regarding confidence in science and objectivity and an inclination to regulate food markets from public and private politics. As he mentions, this regulation culture can be viewed as a form of governability, connecting science, technology, and state formation. Moreover, the search for food regulation through nutritional facts also had a background form of state deregulation. These methodological and theoretical proposals can also help to study the formation of a liberal state and the limits of individual choices related to technologies outside the United States. For example, taking the case of the European Union and some Latin American countries, such as Chile and Mexico, which have also initiated their national food regulation policies, Frohlich’s definition of regulatory culture can be expanded in the future by focusing on other cases with a global perspective.

Whereas the book centers around “Americans’ relationship to food” (p. 20), and the evolution of nutritional facts during the twentieth century, it covers other themes, including the role of experts and expertise, consumerism, marketing techniques, and public and private spheres, all linking to the complex relationship between food and science through informative elements. Today, following Frohlich’s proposals, the study of this relationship opens doors toward a wider historiography of technology and food studies. But it also connects to the current public debates about the negatives associated with the production and consumption of genetically modified food, the consumers’ search for organic food production, and the medical –and pseudo-medical– information to which we are exposed daily about how to eat “correctly.”

Yohad Zacarías is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. As a Fulbright doctoral fellow, her interests focus on electrification’s urban, environmental, and technological impact in Chile and Latin America between the 19th and 20th centuries. As a pre-doctoral project, she is researching the history of design and everyday technology in Chile during the 1970s and 1990s through advertising campaigns to reduce electricity consumption.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.