Census records are invaluable historical documents, but they are frustratingly limited, especially when you try to use them to tell the stories of formerly enslaved people. One example is Bondy Washington, a woman likely trafficked from Africa into slavery who became a long-term Austin resident.

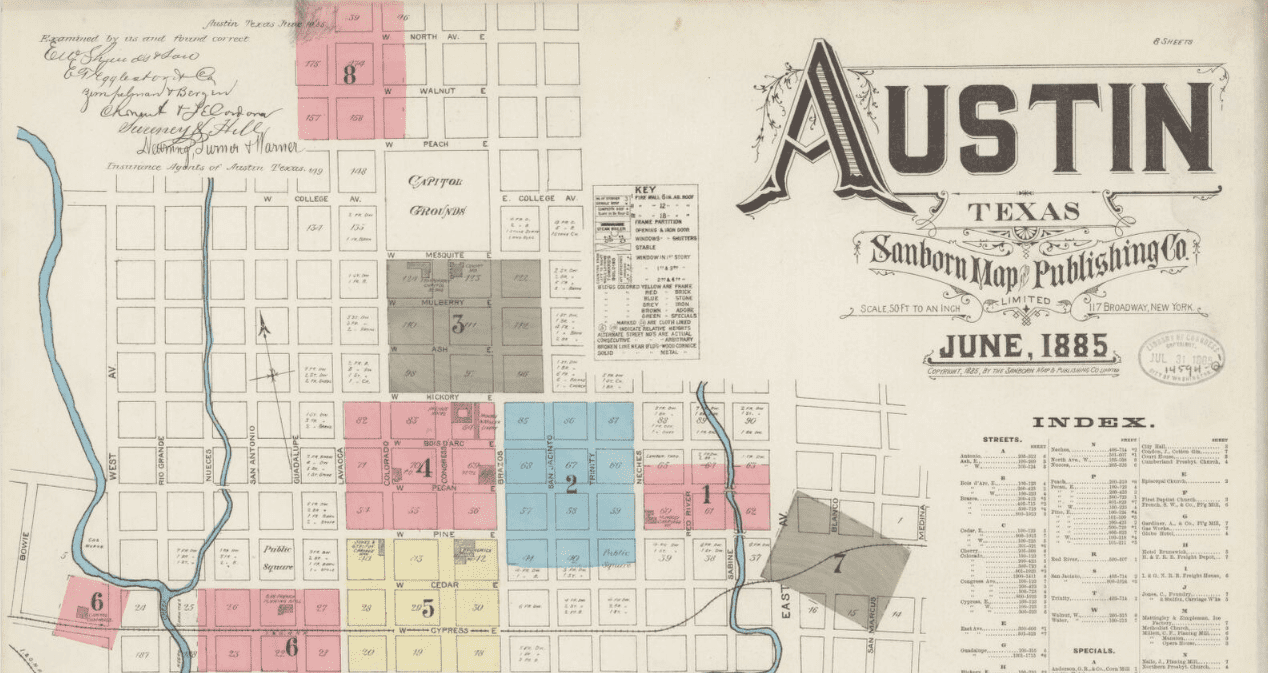

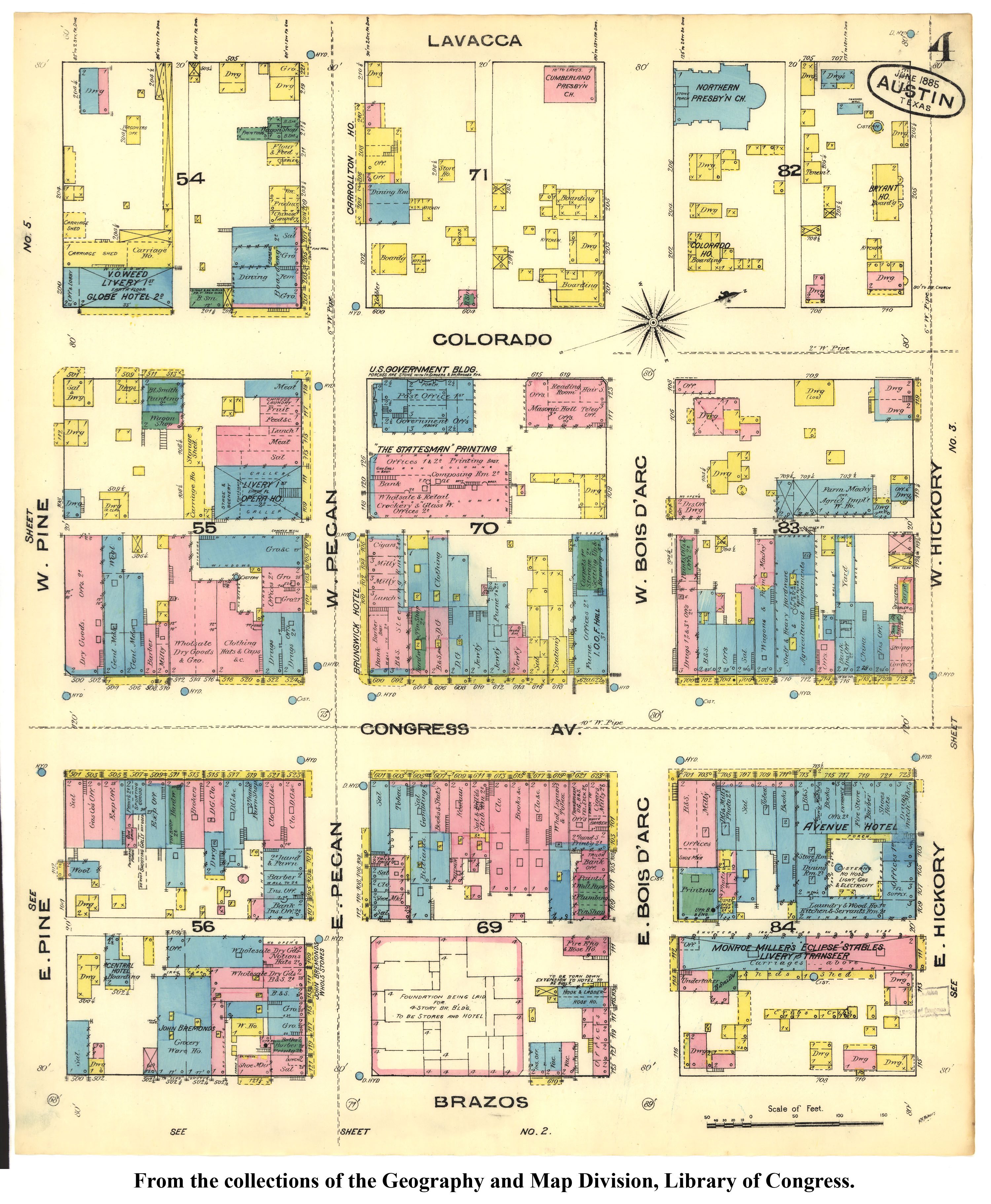

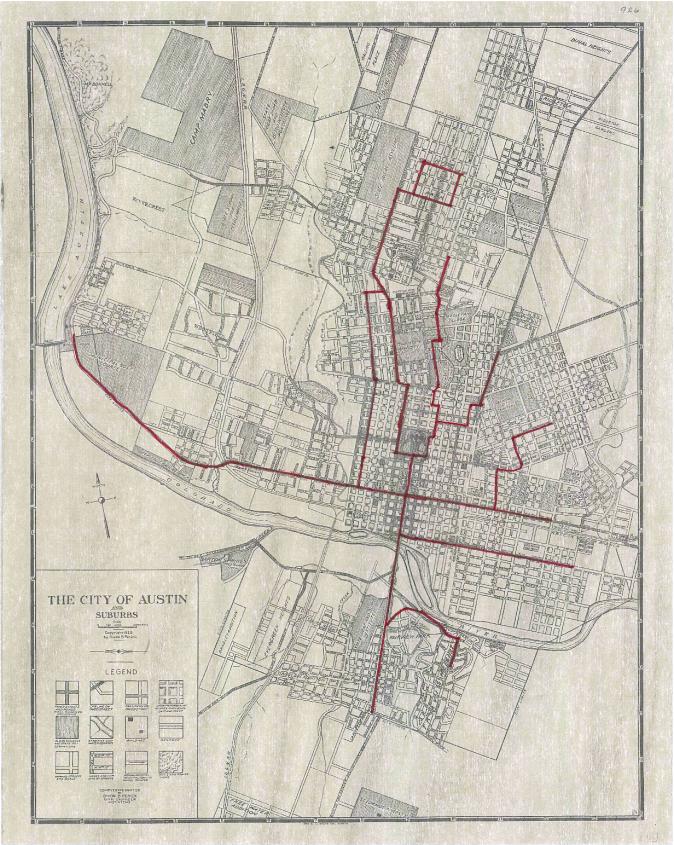

For the past three years, I have been working with Dr. Edmund T. Gordon to create demographic maps of Austin, Texas from 1880-1950. These maps were created with massive amounts of census data—over 372,000 people’s information was transcribed from thousands of scanned pages across seven decades. When we completed this large database, I calculated some other large aggregate figures, beginning with the 1880 census.

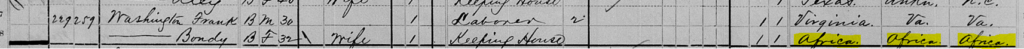

In 1880, 49.99 percent of Austin residents were born in Texas. In today’s terms, that would mean almost half a million people, but back in the late nineteenth century, this figure was less than six thousand or 5,481, to be precise. Digging deeper into the census figures, I found an intriguing data point—one. In 1880, one person in Austin was born in Africa. Her name was Bondy Washington, and she was a Black woman.

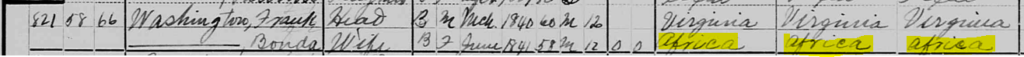

At first, I thought that this could be a transcription error. I checked the original document and saw that the person recording her information had in fact written “Africa” as her birthplace.

I also found Bondy in the 1900 Census. Again, Bondy’s birthplace is recorded as Africa.

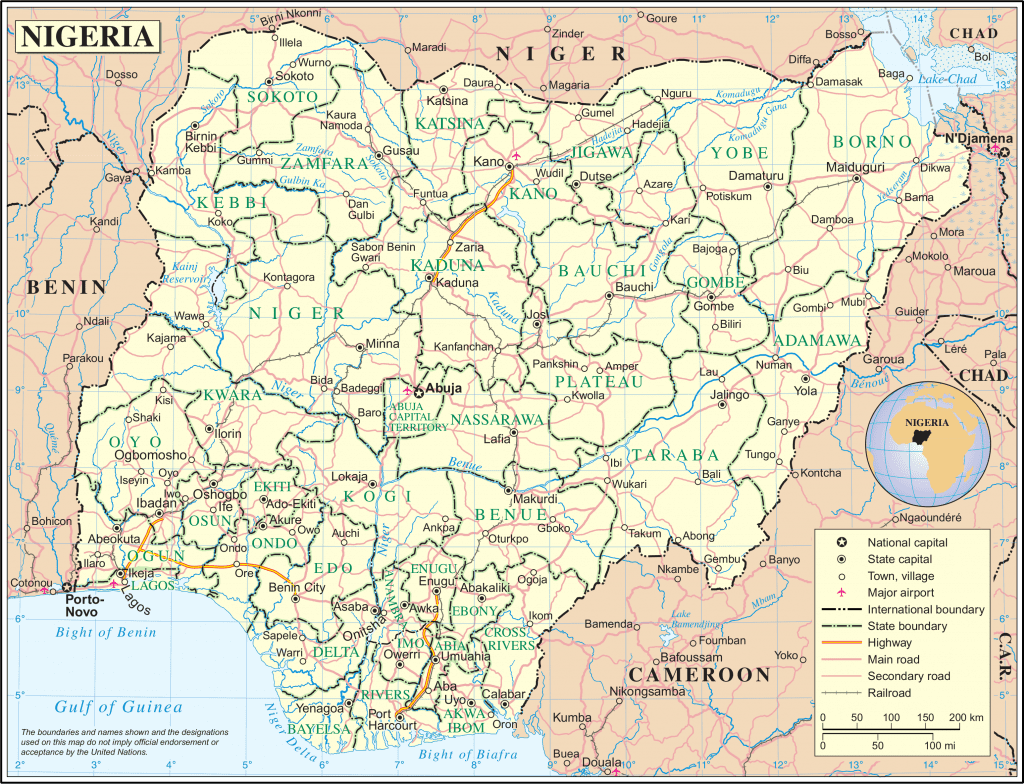

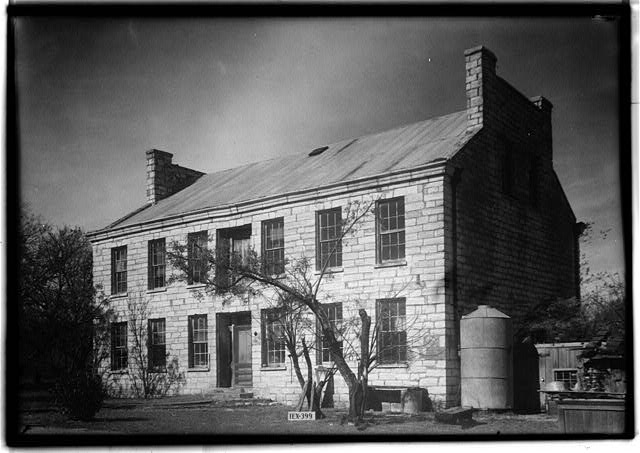

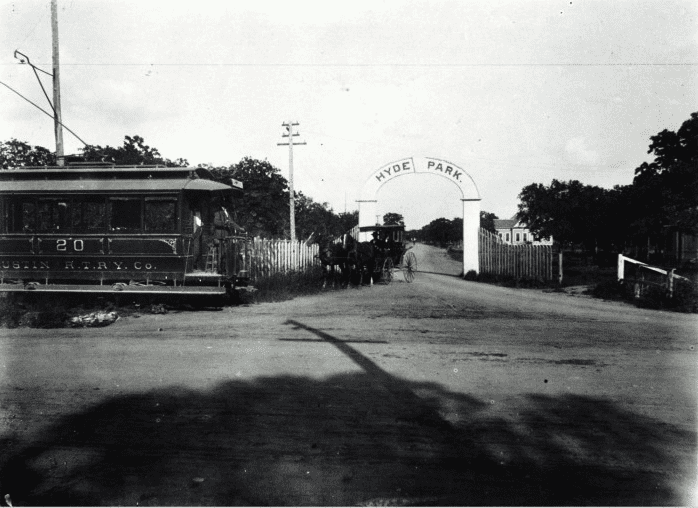

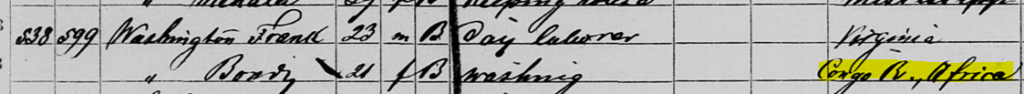

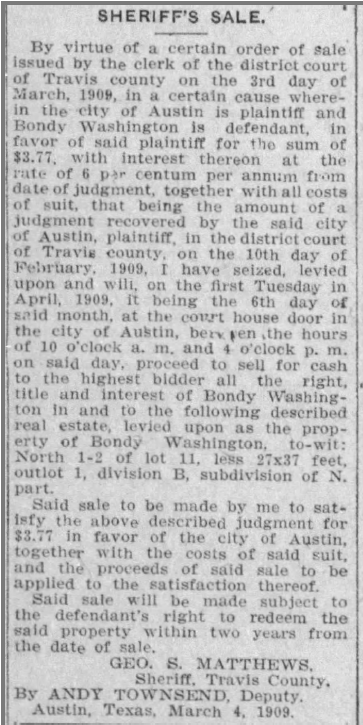

Bondy wasn’t in my database again after 1900, but I became fascinated with her story and decided to dig deeper. The earliest record that I can confidently match to her dates from 1870. In this census, Bondy’s birthplace is recorded as “Congo R., Africa.” She is listed as living with a man named Frank, who, in other censuses, is recorded as her husband. Several city directories from 1880 to 1900 mention Frank, all associating him with the same address—821 E 11th Street, in a neighborhood then known as Robertson’s Hill. It is safe to assume that Bondy also lived there and that her exclusion was probably related to her gender. City directories from 1903 and 1906 associate Bondy with the same address. Frank, who was left out of these documents, possibly passed away between 1900 and 1903.

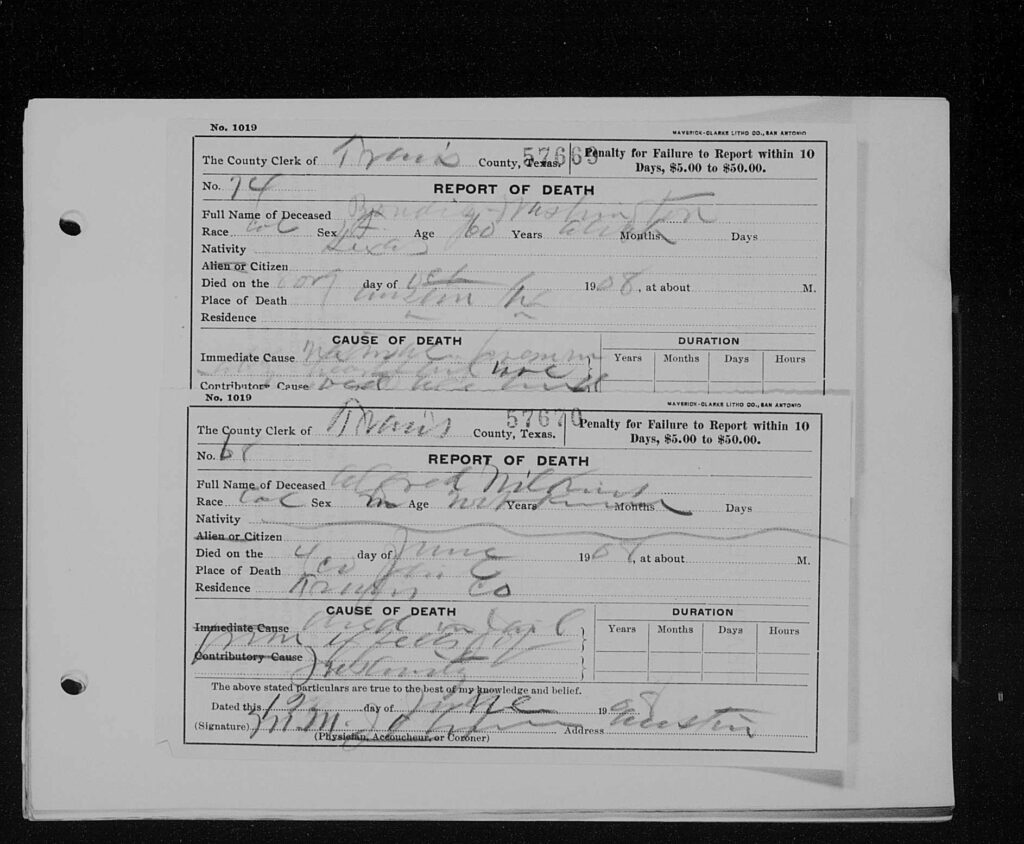

I later found Travis County death certificate for a Black woman named “Bondig Washington.” Despite the error, I believe that this is likely the same person. While people provide their own information in the census and directories, someone else must record their death certificate. In this case, the (white) county clerk filled it out and recorded Bondy’s birthplace as Texas. In her death, her place of birth was erased.

Already, Bondy has a remarkable story: a Black woman born in Africa around 1850 was brought to Austin, TX and lived in the same place for more than thirty years. But what else can we know about her? Who was she before 1870, and who was she before emancipation?

It’s impossible to say what her life was like, but Bondy was likely trafficked to the United States from Congo as a child. She had enough memory of this to claim her birthplace as Africa on records she filled out personally.

Bondy’s African origins are especially puzzling when considered in the context of the legality of the slave trade. When the United States Constitution was written, its authors agreed to allow the trafficking of African slaves into the county until at least 1808. In 1807, President Thomas Jefferson signed into law a bill banning the practice starting the next year. Because Texas was not a part of the United States, and was rather a part of Mexican territory, it was not beholden to this rule. The Mexican government banned the importation of slaves into Texas in 1824. When Texas became a Republic, its constitution also banned the practice.

Source: Slave Voyages

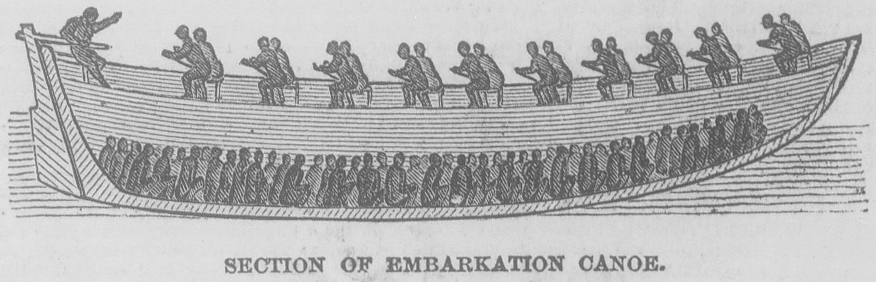

So, if Bondy was brought to Texas to be enslaved, she was brought illegally. Historians have written about the illegal slave trade in Texas in the republican period and thereafter. They have documented that the illegal slave trade continued through the 1850s, sometimes on ships purporting to import camels into the United States.

American politicians generated a scheme to allow for clandestine trafficking of Africans to the United States. They petitioned the United States War Department to allow the importation of camels for use in domestic combat. This gave large cargo ships travelling to West Africa a cover story—their large holds were for military camels, not slaves. The last speculated instance of this practice was in 1856.

Illegal trafficking continued during Bondy’s early years, and it is likely that this is how she came to the United States. We can’t know, though, how she was brought there—on a camel ship or otherwise. Rare is the slave ship that records the names of its passengers. Certainly, an illegal slave ship trafficking people to the United States in the 1850s didn’t leave such traces. Even if they did, who knows the name Bondy was given by her mother? Who knows if she changed it once she landed in Texas or had it changed for her?

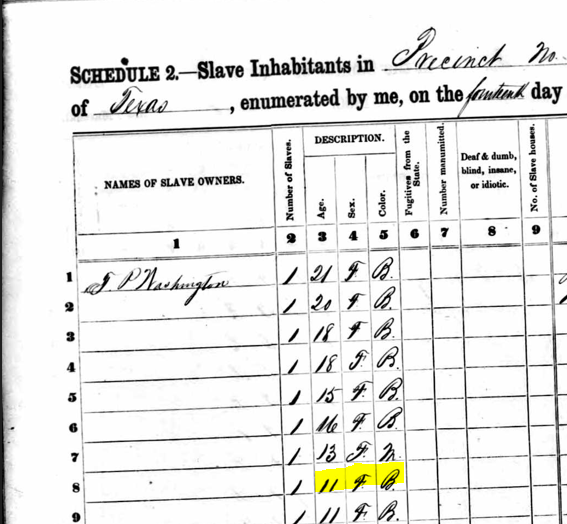

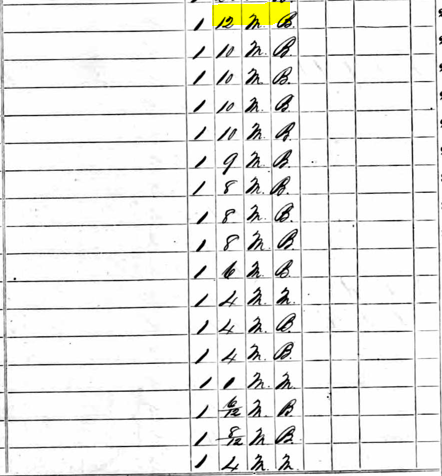

Ship records weren’t the only ones that excluded people’s names. The 1860 slave census records the number of people an individual enslaved, but it completely omits their names. As such, it would be impossible to identify Bondy in the slave registers. However, there is one potential lead. Someone in the Austin area with the surname “Washington” enslaved, among many others, two people of the same ages that Bondy and Frank would have been in 1860. Since some people took the surnames of their enslavers upon emancipation, it is possible that these two people were Bondy and Frank.

Because those collecting their information recorded them as property and not people, we don’t know the names of those two people, and we don’t know who they are.

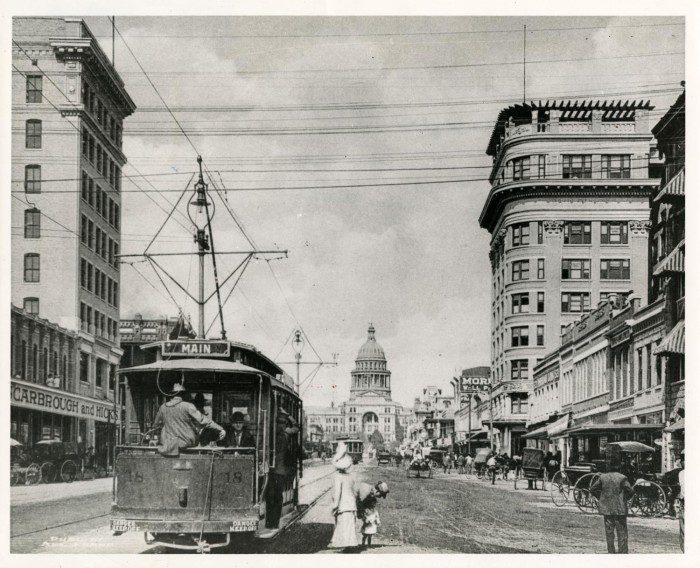

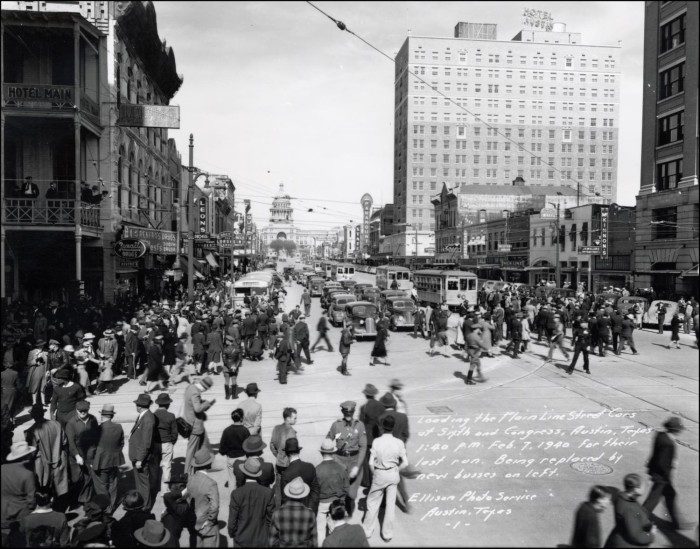

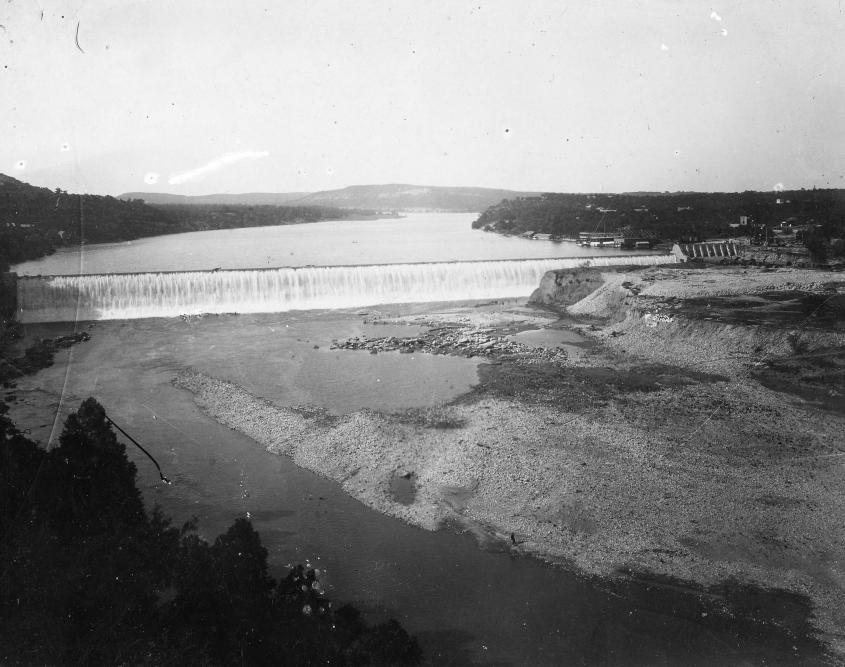

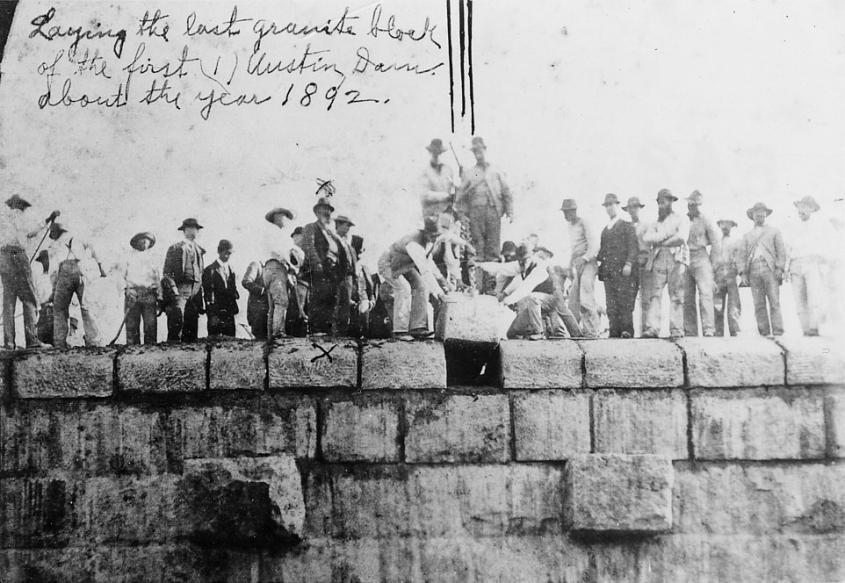

We do know some things. Bondy was from Africa, and she lived in Austin. Bondy and Frank probably built that house themselves, and they lived there for decades. They lived in a neighborhood that is today so utterly transformed by modernity, segregation, and gentrification.

Bondy had no children, so no personal genealogical inquiries would have made her story known. Our project has the potential to find other people in Austin with unique stories. By looking at big data, we can find individuals with differences. However, there are still limitations to what we can know because of what was recorded in the past.

Amy Shreeve Bridges is a J.D. Candidate at Yale Law School and a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. While pursuing her undergraduate degree in history, she completed digital humanities and urban geography research that focused on mapping the racial geography of historic Austin. Her research interests include historical GIS, segregation, and urban housing policies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

References

“912 E 11th Street,” Google Streetview, March 2024, https://www.google.com/maps/@30.2698205,-97.7309772,3a,75y,209.52h,104.14t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1syJa1RPhIgQNCmJL-o4CPKg!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fpanoid%3DyJa1RPhIgQNCmJL-o4CPKg%26cb_client%3Dmaps_sv.share%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26yaw%3D209.52129397598353%26pitch%3D-14.140192174838944%26thumbfov%3D90!7i16384!8i8192?coh=205410&entry=ttu.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 168. Morrison & Foumy. 1881.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 239. Morrison & Foumy. 1887.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 258. Morrison & Foumy. 1891.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 288. Morrison & Foumy. 1893.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 297. Morrison & Foumy. 1895.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 273. Morrison & Foumy. 1903.

Austin, Texas, City Directory, pg 285. Morrison & Foumy. 1906.

“Sherrif’s Sale,” Austin Statesman, March 16, 1909. https://www.newspapers.com/image/366290646

Barker, Eugene C. “The African Slave Trade in Texas.” The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association 6, no. 2 (1902): 145–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784929.

Koch, Augustus. Austin, State Capital of Texas. 1887. Lithograph, 28 x 41 in. Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

“Racial Mapping Austin,” Central Texas Retold, accessed June 19, 2024, https://ctxretold.org/black-communities/mapping-the-city/.

“Report of Death,” Travis County Death Certificates via FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9Y1H-SYKH?view=index), image 1490 of 3319.

U.S. Census Bureau. The Ninth Federal Census (1870); Census Place: Austin, Travis, Texas; Roll: M593_1606; Page: 297A.

U.S. Census Bureau. The Tenth Federal Census (1880); Census Place: Austin, Travis, Texas; Roll: 1329; Page: 262d; Enumeration District: 136.

U.S. Census Bureau. The Twelfth Federal Census (1900); Census Place: Austin Ward 8, Travis, Texas; Roll: 1673; Page: 3; Enumeration District: 0096

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.