by Tiana Wilson

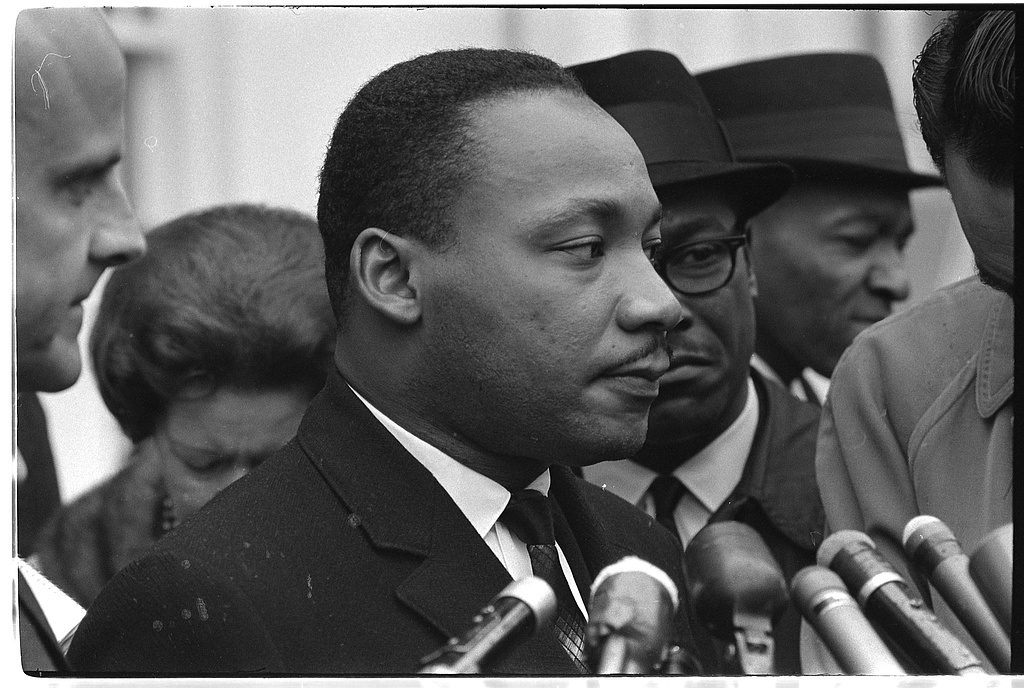

As we approach the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the 50th anniversary of his death, April 4, 1968, it is crucial to appreciate King entirely. Beyond his push for nonviolent direct action and racial integration, we should recognize his expansive human rights activism, anti-war advocacy, and ground-breaking thinking.

Harvard Sitkoff’s biography of King shows him as a heroic but flawed leader and emphasizes his radicalism rather than his pacifism. Sitkoff does not shy away from King’s shortcomings. He brings attention to King’s adultery and highlights the criticism he faced from others within the movement. His portrait of King shows him to be a man who made mistakes, feared death, belittled women, gambled, partied, and often compromised. However, it was also clear that King was intelligent, strategic, pious, courageous, radical, well spoken, passionate, and loving at heart. Sitkoff argues that King’s view of the civil rights movement shifted. At the beginning of the movement, the goal was to end Jim Crow and obtain voting rights. However, after King’s experience in the urban north, he knew that the civil rights movement needed to expand to include economic and job security as well as housing reform. By the end of King’s life he was a firm advocate of anti-colonialism and opponent of war and he took a global perspective: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Stikoff’s book is organized around the key events that shaped King’s leadership. The most compelling argument Stikoff makes is that King was an activist first and then a preacher. He argues that King resisted becoming a pastor and only decided to go into ministry because he knew that it was the best strategic method to get his political agenda across. However, I do think that King was deeply spiritual and used religion to strengthen himself as he became the symbol of the movement and a target of its opponents. King also knew that the south was deeply religious and biblical references would appeal to his supporters. On the other hand, using the black church as the center point for the movement worked in the south but was unsuccessful in the north. De facto segregation complicated urban issues in Chicago and New York, where nonviolent direct action was not as effective as it had been in the south. Shadowing King’s life as the leader of the civil rights movement was was the infamous harassment of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover. The FBI’s strict surveillance of King was made prevalent throughout the book, which shows how the system that was supposed to protect King was actually out to destroy him.

Reexamining the legacy and life of Martin Luther King gives us insight into the ways that social movements can be used to make radical changes in the United States and the ways those changes can make their leaders into targets.

You may also like:

1863 in 1963 by Laurie Green

Stokely Carmichael: A Life by Peniel Joseph

Matt Tribbe reviews Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

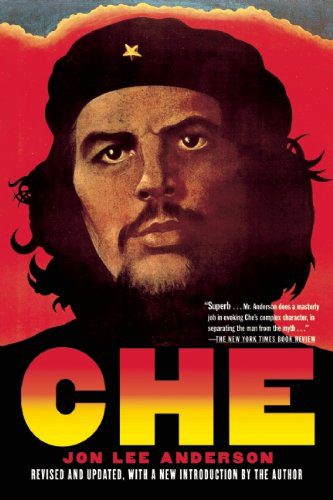

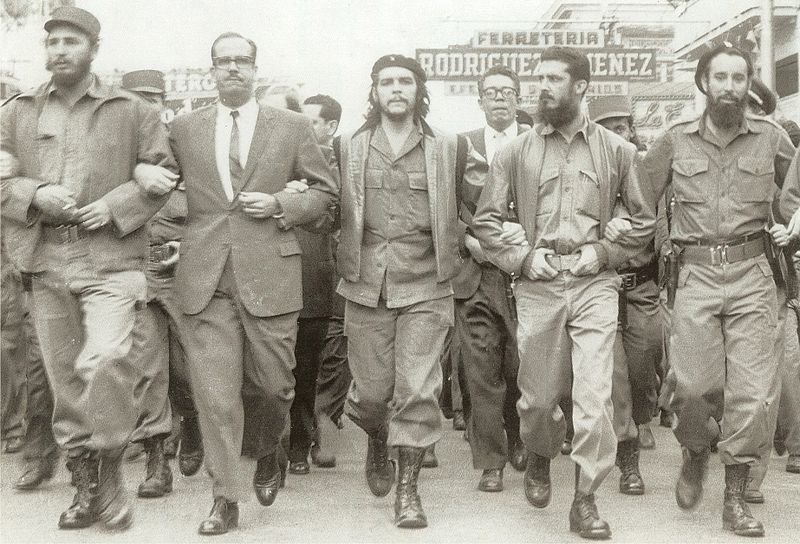

Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing

Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing

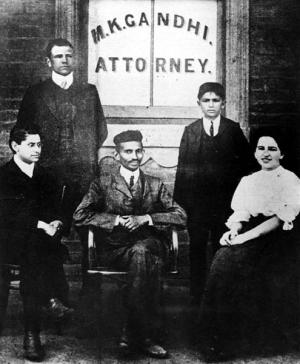

Perhaps aware of this difficulty, Joseph Lelyveld sets himself a modest goal to “amplify rather than replace the standard narrative” of Gandhi’s life. The

Perhaps aware of this difficulty, Joseph Lelyveld sets himself a modest goal to “amplify rather than replace the standard narrative” of Gandhi’s life. The  by

by