For so many students this year, the cancellation of commencement meant the lack of an important milestone. And in this unsettling time, with it many demands on our attention, it’s possible to overlook the extraordinary accomplishment involved in completing a PhD in History. So we decided to take this opportunity to celebrate the 2019-2020 class of new UT Austin History PhDs and tell you a little about them and their work.

Each of these students completed at least two years of course work. They read hundreds of books and wrote dozens of papers to prepare for their comprehensive examinations. After that, they developed original research projects to answer questions no one had asked before. Then they did a year or so of research in libraries and archives, before sitting down to write their dissertations. They did all this while working, teaching, caring for their families, having at least a little fun, and, in some cases, writing for Not Even Past!

Here they are, with their dissertation titles (and abstracts, if we have them). CONGRATULATIONS DOCTORS!

Sandy Chang, Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, University of Florida

“Across the South Seas: Gender, Intimacy, and Chinese Migrants in British Malaya, 1870s-1930s”

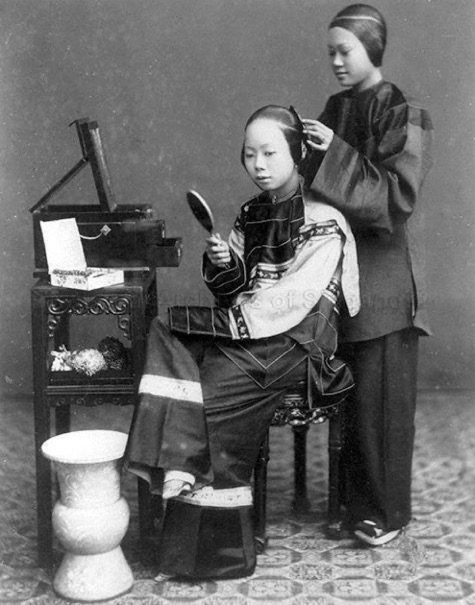

Across the South Seas explores the migration of Chinese women who embarked on border-crossing journeys, arriving in British Malaya as wives, domestic servants, and prostitutes. Between the 1870s and 1930s, hundreds of thousands of women traveled to the Peninsula at a time when modern migration control first emerged as a system of racial exclusion, curtailing Asian mobility into white settler colonies and nation-states. In colonial Malaya, however, Chinese women encountered a different set of racial, gender, and sexual politics at the border and beyond. Based on facilitation rather than exclusion, colonial immigration policies selectively encouraged Chinese female settlement across the Peninsula. Weaving together histories of colonial sexual economy, Chinese migration, and the globalization of border control, this study foregrounds the role of itinerant women during Asia’s mobility revolution. It argues that Chinese women’s intimate labor ultimately served as a crucial linchpin that sustained the Chinese overseas community in colonial Southeast Asia.

Sandy Chang on Not Even Past:

Podcasting Migration: Wives, Servants, and Prostitutes

A Historian’s Gaze: Women, Law, and the Colonial Archives of Singapore

Chinese Lady-in-Waiting Attending to Her Chinese Mistress’ Hair, c.1880s (Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore).

Itay Eisinger

“The Dystopian Turn In Hebrew Literature”

From its inception in Europe during the final decades of the nineteenth century, the Zionist movement promoted, leveraged and drove forward a utopian plan for a Jewish national revival, in the biblical Land of Israel, and in essence framed these plans as a pseudo divine right of the Jewish people. Numerous intellectual, cultural and literary historians therefore have focused on the role of utopian thinking in the shaping of Zionist ideology and Hebrew literature. By way of contrast, this dissertation focuses on the transformation, or evolution, of dystopian poetics within the realm of modern Hebrew literature. … Recent scholarship argues that while early “totalitarian” dystopias tended to focus on the dangers of the all-powerful state, tyranny, and global isolation as the main sources of collective danger to a prosperous and peaceful future, more recently published dystopias – both in the West and in Israel – have moved their focus to other topics and hazards, such as catastrophic ecological or climate disasters, patriarchy, sexism and misogyny, and the rise of surveillance and the integration of the intelligence community into the all-powerful well-oiled capitalist machine. While I do not disavow such arguments completely, I argue that most Israeli dystopias are still driven primarily by the traditional depiction of an authoritarian-fascist regime run amok – in alignment with the Huxley-Orwell model – while at the same time, explore creatively a vision of Yeshayahu Leibowitz’s prediction in 1967 that the Israeli Occupation of the Palestinians would inevitably force Israel to become a “police state.” … I examine the common themes found in these novels, including the dystopian depiction of an instrumentalization of the Shoah and manipulative abuse of the memory of the Holocaust in order to promote political agendas, allusions to the nakba, the over-militarism and nationalism of the state, the effects of the Occupation on Israeli society, and Israel’s neoliberal revolution…. By examining these novels from this perspective, and creating a dialogue between these works and different critical scholars, this dissertation aims to contribute to the study of Israel by rethinking its history – through the prism of dystopia.

Itay Eisinger on Not Even Past:

Rabin’s Assassination Twenty Years Later

Carl Forsberg, 2019-2020 Ernest May Postdoctoral Fellow in History and Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center, 2020-2021 Postdoctoral Fellow with Yale’s International Security Studies Program and the Johnson Center for the Study of American Diplomacy.

“A Diplomatic Counterrevolution: The Transformation Of The US-Middle East Alliance System In The 1970s”

This dissertation charts the agency of Arab, Iranian, and US elites in transforming the structure of Middle Eastern regional politics and constructing a coalition that persists to the present. In the decade after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, the regimes of Anwar Sadat in Egypt, King Faisal in Saudi Arabia, and Shah Mohamad Reza Pahlavi in Iran set out to overturn the legacy of Nasserism and Arab socialism. Animated by a common fear that their internal opposition gained strength from a nexus of Soviet subversion and the transnational left, these regimes collaboratively forged a new regional order built around the primacy of state interests and the security of authoritarian rule. They instrumentally manipulated a range of US-led peace processes, including Arab-Israeli negotiations, US-Soviet détente, and conciliation between Iran and its Arab neighbors to advance their diplomatic counter-revolution. US administrations at times resisted these efforts because they read the region through the polarities of the Arab-Israeli conflict. After the 1973 War, however, the opportunity to marginalize Soviet influence in the region proved too enticing for US officials to ignore. My project deploys multi-lingual research conducted in Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, the UK, and the US. To overcome the lack of open state archives in Arab countries, the dissertation examines US, British, Iranian, and Israeli records of discussions with Arab leaders, as well as memoirs, periodicals, and speeches in Farsi and Arabic, to triangulate the strategies and covert negotiations of Arab regimes.

Celeste Ward Gventer, Post-doc, The Albritton Center for Grand Strategy at the Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University.

“Defense Reorganization For Unity: The Unified Combatant Command System, The 1958 Defense Reorganization Act And The Sixty-Year Drive For Unity In Grand Strategy And Military Doctrine”

This dissertation seeks to answer a deceptively simple question: why, in 1958 and as part of the Defense Reorganization Act (DRA) passed that year, did U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower remove the chiefs of the military services from the chain of operational command and instead empower the so-called “unified combatant commands” to lead American military forces in war? The answer, this dissertation will argue, is that Eisenhower had found himself competing with his military service chiefs for his entire first administration and the first half of his second over national (grand) strategy and military doctrine. Taking those service chiefs out of the chain of operational command would, in effect, diminish the role of those officers. Eisenhower had found that simply getting rid of refractory officers was insufficient to quiet their rebellion: only by suppressing their role permanently in the bureaucracy did he hope to unify American strategy- and policy-making. This interpretation is at odds with the few accounts of the 1958 DRA that do exist, which tend to take Eisenhower’s stated purposes—to enhance “unity of command”—at face value. The circumstances that led Eisenhower to take this step were decades, if not longer, in the making. … The situation resulted from the inherent pluralism in American military policy making … it was also a product of the decades that preceded Eisenhower’s administration during which the American military was consistently forced to “fill in the blanks” of national strategy. What drove matters to a head in the 1950s was the steady growth of American power after the 1898 Spanish-American War and, especially, after the Second World War. It is necessary to also appreciate several legacies Eisenhower confronted and that colored his own views: the history of American military thinking about command and about civilian control; the creation of military staffs and the process of reform and professionalization inside the military services during the twentieth century; and the development of independent service doctrines. … This work will trace these conceptual threads over the sixty-year rise of the United States to a global power, culminating in Eisenhower’s standoff with his service chiefs in the 1950s.

Lauren Henley, Assistant Professor, University of Richmond

“Constructing Clementine: Murder, Terror, and the (Un)Making of Community in the Rural South, 1900-1930”

Deirdre Lannon, Senior Lecturer, Department of History, Texas State University

“Ruth Mary Reynolds And The Fight For Puerto Rico’s Independence”

Ruth Mary Reynolds (Women in Peace)

This dissertation is a biography of Ruth Mary Reynolds, a pacifist from the Black Hills of South Dakota who after moving to New York City became involved in the movement for Puerto Rico’s independence…. She bucked the social norms of her conservative hometown to join the Harlem Ashram…. Her work within the Ashram connected her to the web of leftist coalition activism launched by the Popular Front era of the 1930s and 1940s, and to A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington Movement for black equality. She became involved with organized pacifism, most notably through her membership in the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and her close friendship with its U.S. leader, Dutch-born theologian A.J. Muste. In 1944, Ruth decided to make the issue of Puerto Rico’s independence her own. She helped form a short-lived organization, the American League for Puerto Rico’s Independence, which was supported by Nobel Laureate Pearl S. Buck among others. She became close friends with Pedro Albizu Campos and his family, as well as other Puerto Rican independence activists. She traveled to Puerto Rico, and in 1950 found herself swept into the violence that erupted between the government and Albizu Campos’s followers. Her experiences in New York and Puerto Rico offer a unique lens into the ways in which the Puerto Rican independence movement functioned, and how it was quashed through governmental repressions. Her friendship with Pedro Albizu Campos, the fiery independentista who remains a figurehead of Puerto Rican identity and pride, helps to humanize the man behind the mission. Ruth never abandoned her friend, or their shared cause. She fought for Albizu Campos to be freed, bucking the climate of repression during McCarthyism. This dissertation traces her efforts until 1965, when Albizu Campos died. She remained an active part of the Puerto Rican independence movement until her own death in 1989.

Holly McCarthy

“The Iraq Petroleum Company In Revolutionary Times”

Signe Fourmy, Visiting Research Affiliate, Institute for Historical Studies and Education Consultant, Humanities Texas.

“They Chose Death Over Slavery: Enslaved Women and Infanticide in the Antebellum South”

“They Chose Death Over Slavery,” … examines enslaved women’s acts of infanticide as maternal resistance. Enslaved women occupied a unique position within the slaveholding household. As re/productive laborers, enslavers profited from work women performed in the fields and house, but also from the children they birthed and raised. I argue that enslaved women’s acts of maternal violence bear particular meaning as a rejection of enslavers’ authority over their reproduction and a reflection of the trauma of enslavement. This dissertation identifies and analyzes incidents of infanticide, in Virginia, North Carolina, and Missouri. Using a comparative approach to consider geographic location and household size—factors that shaped the lived experiences of the enslaved—I ask what, if any, patterns existed? What social, economic, and political considerations influenced pivotal legal determinations—including decisions to prosecute, punish, or pardon these women? Expanding on the work of Laura Edwards and Paul Finkelman, I argue that public prosecution and legal outcomes balanced community socio-legal interests in enforcing the law while simultaneously protecting slaveowners profiting from their (re)productive labor. The existing scholarship on slavery, resistance, and reproduction shows that enslaved women were prosecuted for infanticide, yet the only book-length studies of enslaved women and infanticide center on one sensationalized case involving Margaret Garner. Infanticide was more prevalent than the secondary literature suggests. Building upon the work of historians Darlene Clark Hine and Jennifer L. Morgan, I explore how enslaved women re-appropriated their reproductive capacity as a means of resistance. In conversation with Nikki M. Taylor, Sasha Turner, and Marisa Fuentes, I ask what this particular type of violence reveals about the interiority of enslaved women’s lives. Additionally, I explore what these acts of maternal violence reveal about enslaved motherhood—or more specifically an enslaved woman’s decision not to mother her child.

Signe Fourmy on Not Even Past:

Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio by Nikki M. Taylor

Sean Killen

“South Asians and the Creation of International Legal Order, c. 1850-c. 1920: Global Political Thought and Imperial Legal Politics”

Jimena Perry, Teaching Instructor, East Carolina University

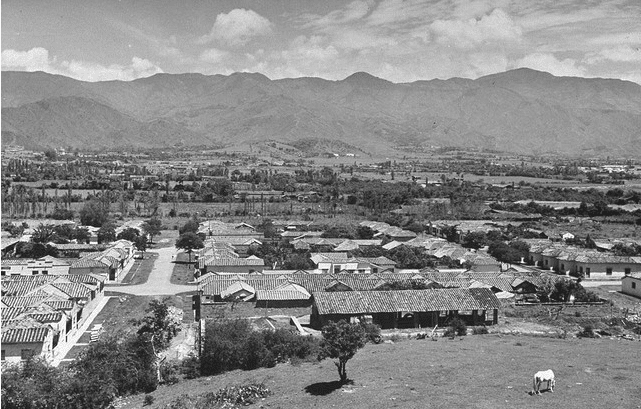

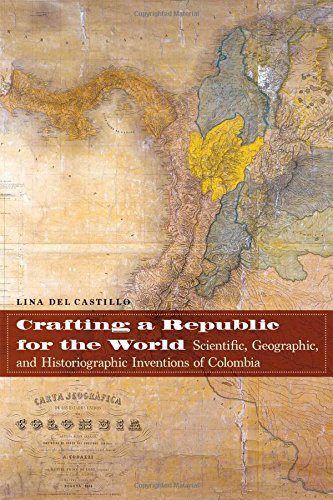

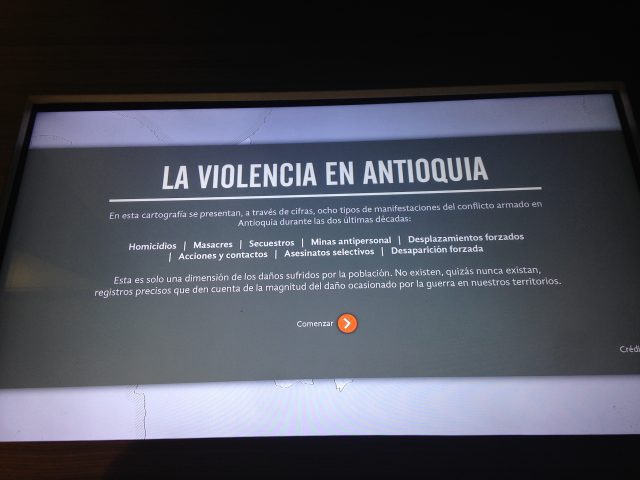

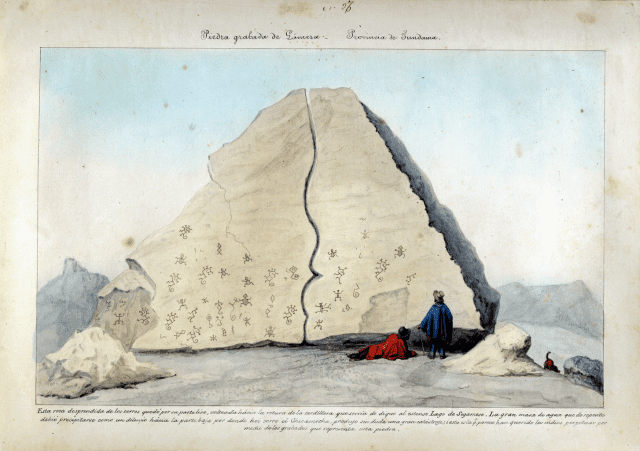

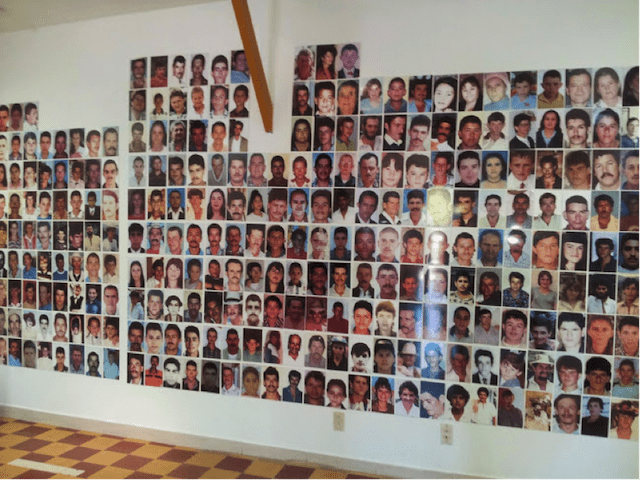

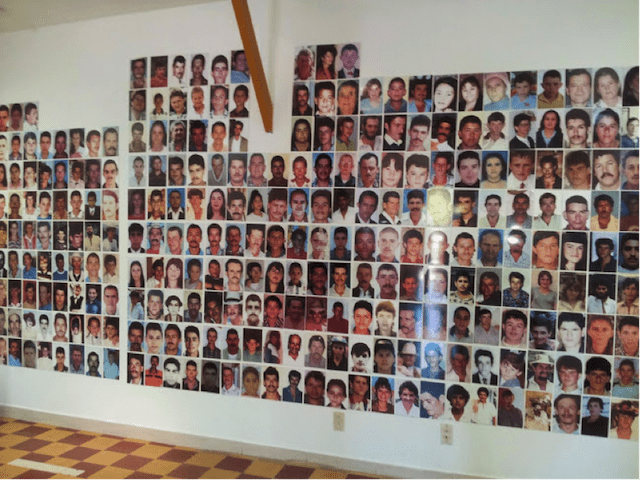

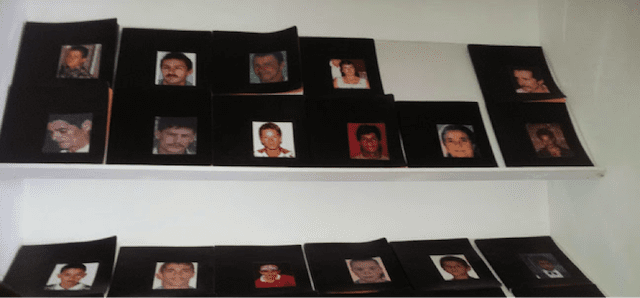

“Trying to Remember: Museums, Exhibitions, and Memories of Violence in Colombia, 2000-2014”

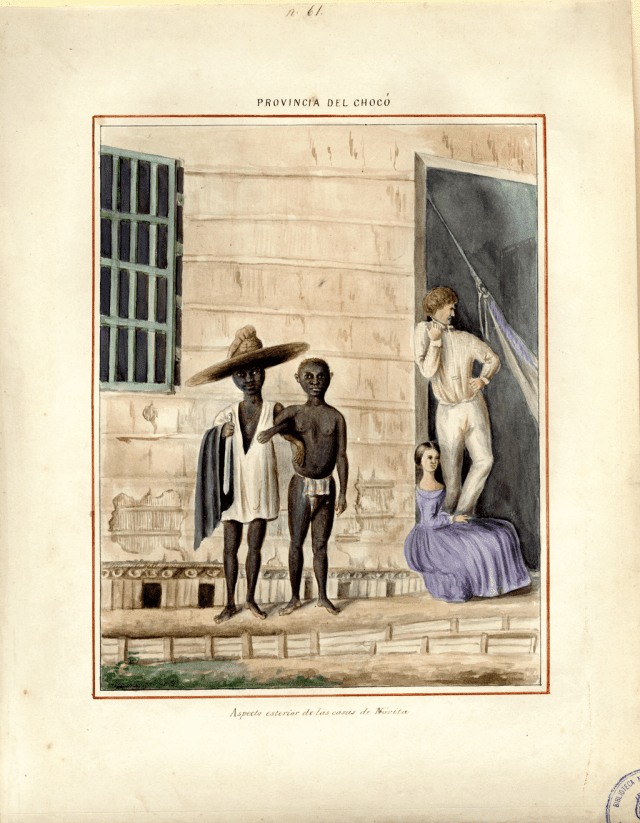

Since the turn of the century, not only museum professionals but grassroots community leaders have undertaken the challenge of memorializing the Colombian armed conflict of the 1980s to the early 2000s. In an attempt to confront the horrors of the massacres, forced displacement, bombings, and disappearances, museums and exhibitions have become one of the tools used to represent and remember the brutalities endured. To demonstrate how historical memories are informed by cultural diversity, my dissertation examines how Colombians remember the brutalities committed by the Army, guerrillas, and paramilitaries during the countryʼs internal war. The chapters of this work delve into four case studies. The first highlights the selections of what not to remember and represent at the National Museum of the country. The second focuses on the well-received memories at the same institution by examining a display made to commemorate the assassination of a demobilized guerrilla fighter. The third discusses how a rural marginal community decided to vividly remember the attacks they experienced by creating a display hall to aid in their collective and individual healing. Lastly, the fourth, also about a rural peripheric community, discusses their particular way of remembering, which emphasizes their peasant oral traditions through a traveling venue. Bringing violence, memory, and museum studies together, my work contributes to our understanding of how social groups severely impacted by atrocities recreate and remember their violent experiences. In addition, my case studies exemplify why it is necessary to hear the multiple voices of conflict survivors, especially in a country with a long history of violence like Colombia. Drawing on displays, newspapers, interviews, catalogs, and oral histories, I study how museums and exhibitions in Colombia become politically active subjects in the acts of reflection and mourning, and how they foster new relationships between the state and society. My work also analyzes museums and displays as arbiters of social memory. It asks how representations of violence serve in processes of transitional justice and promotion of human rights for societies that have been racked by decades of violence.

Jimena Perry on Not Even Past:

When Answers Are Not Enough: The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

More Than Archives: Dealing with Unfinished History

Too Much Inclusion? Museo Casa de la Memoria, Medellin, Colombia

Time to Remember: Violence in Museums and Memory, 2000-2014

My Cocaine Museum by Michael Taussig

History Museums: The Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogatá, Colombia

History Museums: The Hall of Never Again

Christina Villareal, Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, The University of Texas at El Paso

“Resisting Colonial Subjugation: The Search for Refuge in the Texas-Louisiana Borderlands, 1714-1803”

This dissertation is a history of the Spanish borderlands from the perspectives of subjugated people in the Gulf Coast. Based on colonial, military, and civil manuscript sources from archives in the United States, Mexico, Spain, and France, it traces the physical movement of Native Americans, soldiers, and African and indigenous slaves who fled conscription, reduction to Catholic missions, or enslavement in the Texas-Louisiana borderlands of the eighteenth century. It reconstructs geographies of resistance to understand how challenges to colonial oppression shaped imperial territory and created alternative spaces for asylum. While the overarching focus of the dissertation is political space-making at the ground-level, the pivotal change occasioned by the Treaty of Paris (1763) serves as the central arc of the dissertation. The treaty, in which Spain acquired Louisiana from France, signified a major imperial transformation of the Gulf Coast. Initiated “from above,” this geopolitical transition expanded the Spanish borderlands over former French territory and altered the locations where Native Americans, soldiers, and enslaved people could find or avoid colonial oppression.

Christina Villareal on Not Even Past

The War on Drugs: How the US and Mexico Jointly Created the Mexican Drug War by Carmen Boullusa and Mike Wallace

Andrew Weiss

“The Virgin and The Pri: Guadalupanismo And Political Governance In Mexico, 1945-1979”

This dissertation explores the dynamic relationship between Catholicism and political governance in Mexico from 1945 until 1979 through the lens of Guadalupanismo. Guadalupanismo (devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe) is a unifying nationalistic force in Mexico. After 1940, Church and state collaborated to promote the Virgin of Guadalupe as a nationalist emblem following decades of divisive state-led religious persecution. Mexico, however, remained officially anticlerical sociopolitical territory. I analyze flashpoints of Guadalupan nationalism to reveal the history of Mexican Church-state relations and Catholic religiosity. These episodes are: the 1945 fiftieth anniversary of the 1895 coronation of the Virgin of Guadalupe; U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 visit to the Basilica of Guadalupe; the construction of the New Basilica in the 1970s (inaugurated in 1976); and Pope John Paul II’s trip to Mexico and the Basilica in 1979. Each of these occasions elicited great popular enthusiasm and participation in public ritual. And each brought politicians in contact with the third rail in Mexican politics: religion. The essential value of the Virgin of Guadalupe, as I show, is that as both a Catholic and a nationalistic icon, she represented an ideal symbolic terrain for the renegotiation and calibration of Church-state relations under PRI rule. I follow these Guadalupan episodes to track the history of Guadalupanismo and interpret the changing Church-state relationship at different junctures in the course of the single-party priísta regime. These junctures (1945, 1962, 1976, and 1979) are relevant because they are representative of classical and degenerative phases of priísmo (the ideology of the ruling party [PRI] that governed Mexico from 1929 until 2000) and cover the episcopates of three major figures who ran the Archdiocese of Mexico for over sixty years. The Church-state covenant was renegotiated over time as seen by the Guadalupan episodes I analyze.

Andrew Weiss on Not Even Past

Plaza of Sacrifices: Gender, Power, and Terror in 1968 Mexico by Elaine Carey

Pictured above (Clockwise from top center): Sandy Chang, Andrew Weiss, Deirdre Lannon, Jimena Perry, Celeste Ward Gventer, Christina Villareal, Itay Eisinger.

Not pictured: Signe Fourmy, Lauren Henley, Sean Killen, Holly McCarthy, Carl Forsberg,

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as