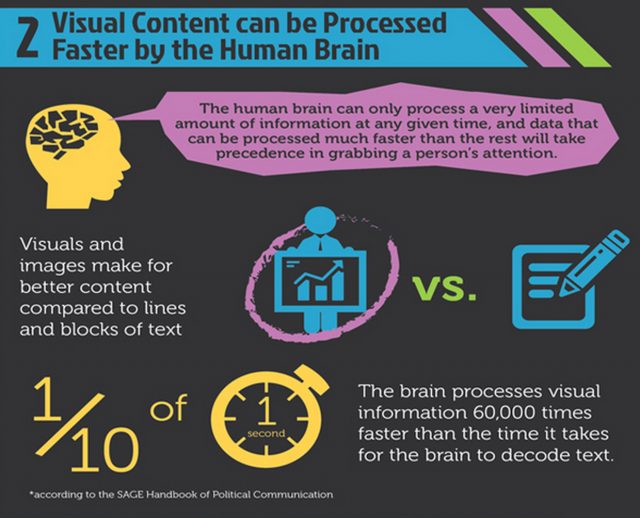

Getting a PhD in History requires us to learn some new skills, but those skills are mostly refinements of things we’ve been practicing since first grade. We have to improve our ability to read carefully, to write lucidly, and to ask increasingly complex questions about what we read. We need to pay attention to the ways historical documents are created and preserved and to the contexts that shape their ideas, but those issues are not qualitatively different from thinking about the books we read in high school and college or the novels we enjoy reading as adults. Digital history, on the other hand, demands entirely new ways of thinking. Building complex digital networks requires me to think like a computer, which is different in significant and interesting ways than thinking like a reader or a writer.

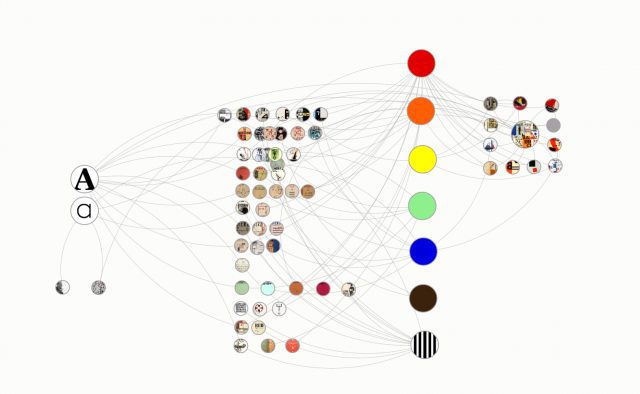

From “Elements of Design in Avant-Garde Magazines,” by Christa Clay, Amanda Jordan, and Natalie Pyle. students in “The Avant Garde in Print,” taught at UT Austin by Meghan Forbes

In my last blog I referred, somewhat skeptically, to Richard White’s contention that constructing a data visualization was itself an analytical project. Here’s the full quote:

“One of the important points that I want to make about visualizations, spatial relations, and spatial history is something that I did not fully understand until I started doing this work and which I have had a hard time communicating fully to my colleagues: visualization and spatial history are not about producing illustrations or maps to communicate things that you have discovered by other means. It is a means of doing research; it generates questions that might otherwise go unasked, it reveals historical relations that might otherwise go unnoticed, and it undermines, or substantiates, stories upon which we build our own versions of the past.”

Now, I get it.

This month I went to two digital history workshops at the annual convention of the American Historical Association. I knew that a three-hour workshop wouldn’t give me all the skills I needed to carry out a social network analysis of the Soviet film industry, but I wanted to figure out whether it would be worth it for me – a pretty old dog – to try to learn some new tricks. I wanted to know if I could manage the computational work on my own without having to raise enough funds to hire a team of computer scientists. And I wanted to know if I am capable of acquiring the skills to make the project yield new questions and interesting answers.

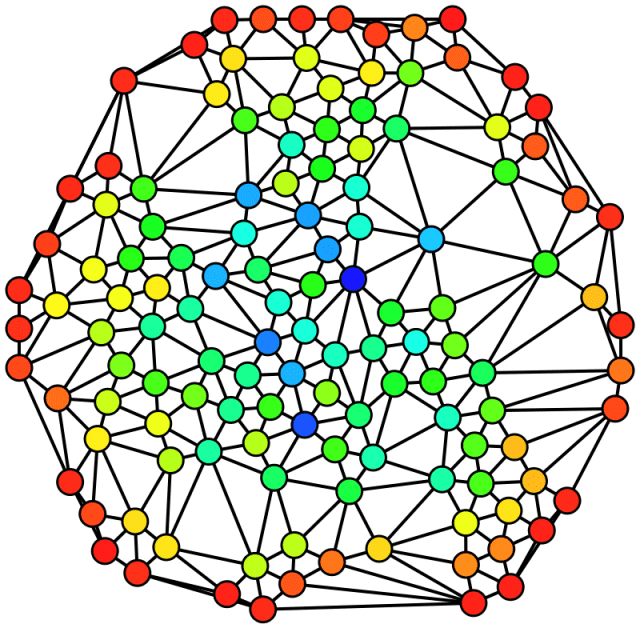

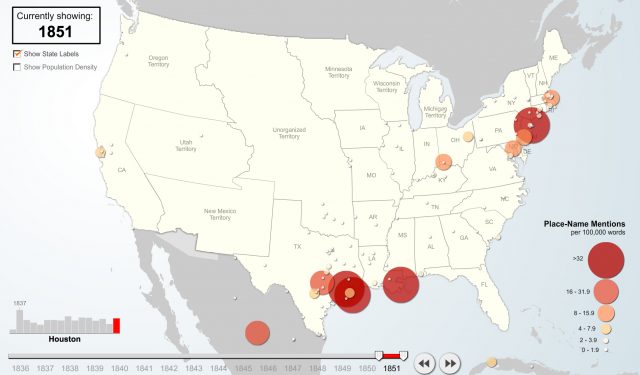

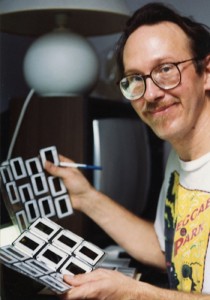

Jason Heppler, an Assistant Professor of History at University of Nebraska at Omaha and a Researcher at the Stanford Spatial History Project, ran the workshop on social network analysis. The goal was to show us the basic functions of the network analysis program, Gephi, an open source program for generating visualizations of networks. We also learned how to use Palladio, an even more user-friendly network analysis program. As with any complex skill, the introduction to these tools was just enough to give us a sense of the range of the program’s main functions. Gephi can take a massive collection of data on relationships and turn it into visualizations (graphs, flowcharts, networks, etc). It can tell us how relationships we might find in a small number of sources play out on a much larger scale. It can display degrees and flow of relationships (friends of friends of friends), suggesting hierarchies of influence and alliances.

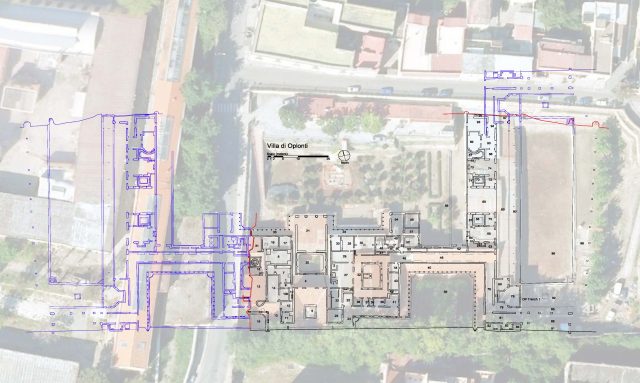

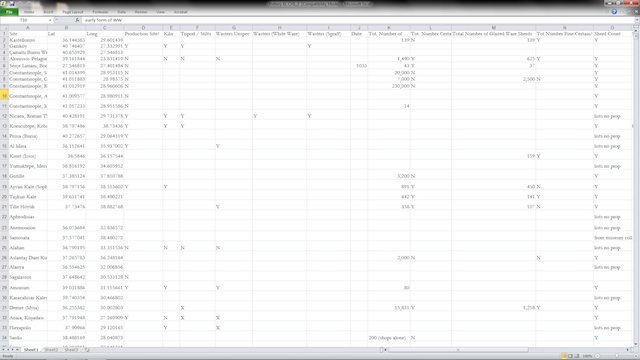

I know I will need more time and repeated practice to learn everything that social networking can do for me, but the introduction demonstrated some of the ways Gephi “thinks” about data, or how I need to think about data in order to work with Gephi. I am interested in analyzing social and political relationships in the Soviet film industry. Right off the bat, I can understand some of the most elementary ways I can track some of those relationships. I understand how I can get Gephi to show me who knew whom, who had the most acquaintances or working partnerships, and how to track those in overlapping ways for an individual’s various roles (as director, teacher, actor, etc). Historians Jamie Miller and Maria Belodubrovskaya have shown the continued influence of some prominent avant garde directors even as Stalinist cultural policies in the 1930s prohibited avant garde filmmaking. I want to know how long that influence remained in effect and on what scale. Did directors tend to work with the same actors? Which party-state administrators had direct contact with which artistic studio administrators? Gephi can weight those kinds of relationships, establishing patterns of contact in a number of interesting ways. The most interesting thing I learned is that Gephi can show something called “betweenness.” So, for example, Person A and Person B may know and be known by the most people, but Gephi can identify a Person C, who might not be personally known by as many people as A and B, but might be a conduit for a higher number of relationships; more people need to contact C in order to reach either A or B. That looks like a promising category for trying to generate new information about people who might not look influential or powerful at first glance.

I was still left with a lot of questions about how I can tell Gephi to code relationships in specific ways. I’d like to be able to show that government bureaucrats who supervised the film industry had important, two-way relationships with the artists who made the films. I’ve written about patron-client relationships between a handful of party-state arts administrators and one film director based on reading documents in the film studio archive that show how people in power made decisions that could only be explained as patronage, but I don’t yet know how I can collect and organize data that shows such relationships and shows them on a larger scale. I don’t yet know how to weigh or color or mark those relationships in order to generate that kind of new knowledge. I am also still trying to decide whether I want to organize my study around a single, influential individual, like the great filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein, or whether I want to organize it more broadly without a single central node.

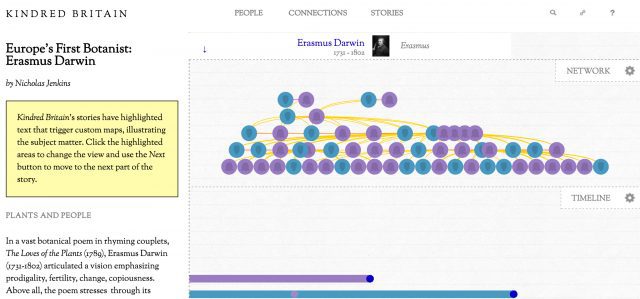

Even more useful than the workshop, therefore, was the drop-in session for digital history that took place on the day after the workshop. There I was able to speak one-on-one with Jason about my particular project. He recommended that I look at some projects organized around a single individual that have used Gephi and Palladio, such as Micki Kaufman’s Quantifying Kissinger. And he recommended some reading, including Scott Weingart, “Demystifying Networks,” Shin-Kap Han, “The Other Ride of Paul Revere,” and Caroline Winterer, “Where is America in the Republic of Letters.” There is also a large literature on networks in other disciplines, all of which I will discuss later on this blog.

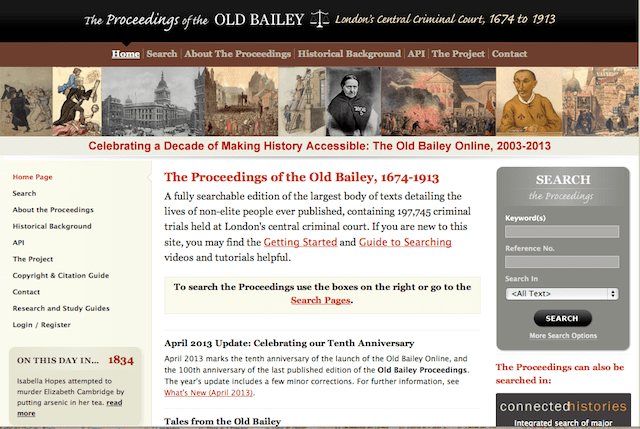

At the drop-in sessions, I was also able to talk to Ian Milligan, another network specialist and an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Waterloo, about web scraping. Ian ran the web scraping workshop the previous day at the AHA. (All his materials are available here.) He walked me through a easy-to-use web scraping tool called import.io and we used it to see how to generate databases from lists of films and their cast and crew on a Russian website called Film-Theater.ru. Like with Gephi, I am going to have to figure out how to adapt the web scraping Ian taught me and I’ll have to start from scratch when I do. Not only will I have to relearn the steps I need to take to use import.io (because once through just wasn’t enough to build those memory pathways in my brain), but I’ll also need to think hard about how to organize and categorize the data I collect.

Looking at documents as a mass of information points that need to be categorized and coded is very different from reading and analyzing masses of documents in order to get a general idea of something and then to pick out the relevant bits of evidence to support the argument I am developing. I am still trying to figure out how I can show power relationships with these tools. One step at a time.

Next time: “From Kissinger to Eisenstein.”

The previous post in this series: Digital Dividends

Information about all the Digital History panels at the AHA 2017 can be found here:

Seth Denbo, “Making Connections: Digital History at AHA17.”

For more on Digital History on Not Even Past, see our series, The New Archive.