During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

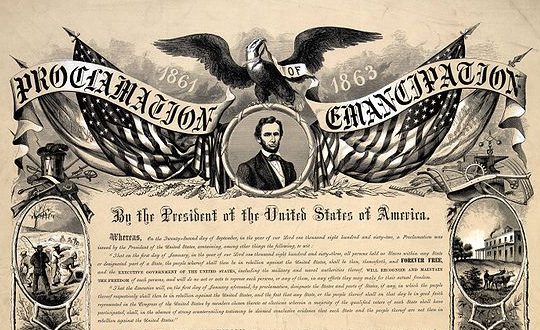

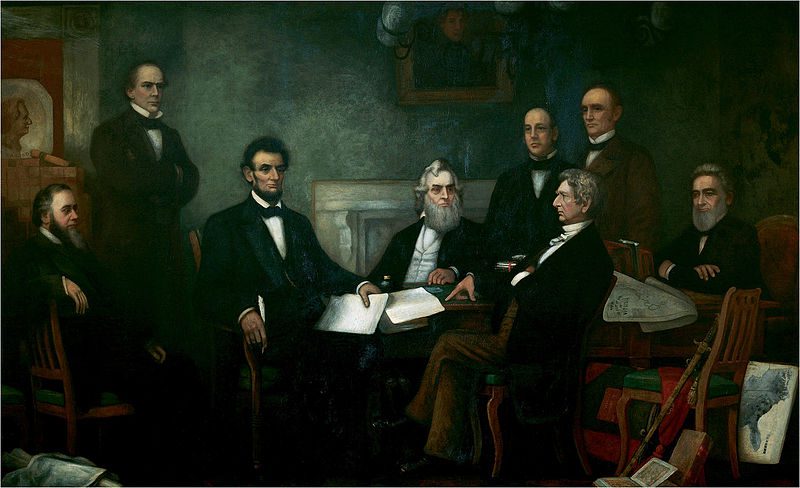

On the afternoon of January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation, freeing approximately three million people held in bondage in the rebel states of the Confederacy. The Emancipation Proclamation was a huge step towards rectifying the atrocity of institutionalized slavery in the United States, but it was only one step and it had a mixed legacy, as these essays by UT Austin historians remind us:

Juliet E. K. Walker examines the contrast between the legal and economic consequences of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Daina Ramey Berry looks at Quentin Tarantino’s sensationalist and willfully inaccurate treatment of slavery in Django Unchained.

George Forgie discusses the political wrangling that accompanied the Emancipation Proclamation, the work it left undone, and the need – that seems so obvious today, but was so deeply contested at the time – for a law abolishing slavery altogether.

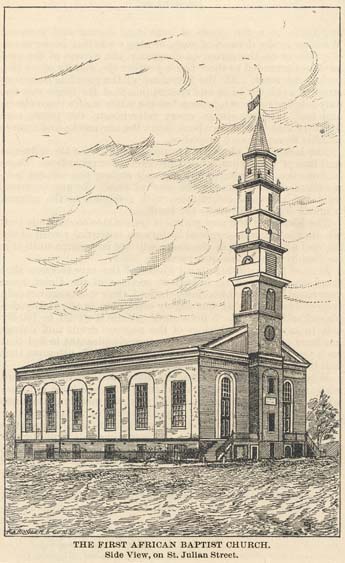

Jacqueline Jones takes us right into Savannah’s African American community on New Year’s Eve, to see and hear how Black Americans there anticipated the momentous news.

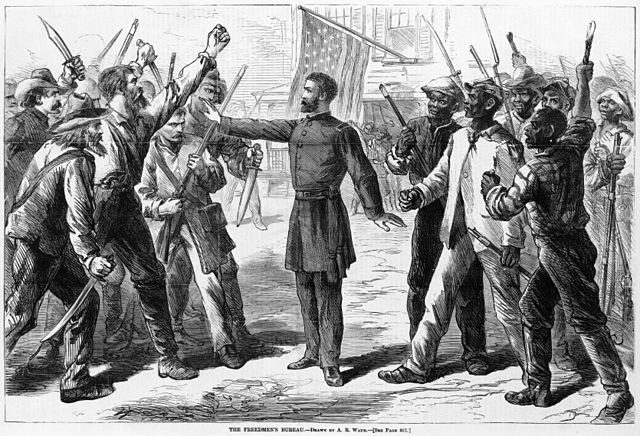

In March 1865, the U. S. Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau for Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands to ease the transition between slavery and freedom for 3.5 million newly liberated slaves. Jacqueline Jones discusses The Freedmen’s Bureau.

Henry Wiencek discusses “Visualizing Emancipation”, a new digital project from the University of Richmond that maps the messy, regionally dispersed and violent process of ending slavery in America.

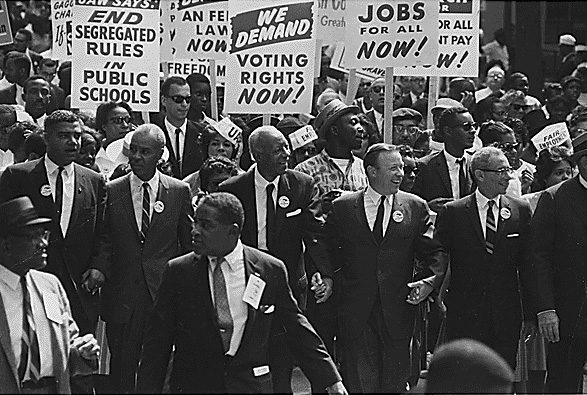

Laurie Green brings us up to 1963 to show us how civil rights activists in the 1960s saw the work of the Emancipation Proclamation as still unfinished.

Recommended Books:

Cristina Metz recommends Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South by Hannah Rosen (University of North Carolina Press, 2008)

Henry Wiencek discusses Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial (W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), which examines Abraham Lincoln’s views on American slavery, southern secession and the convergence of events that produced the Emancipation Proclamation.

Jacqueline Jones recommends more great books on The Emancipation Proclamation and its Aftermath and on Slavery, Abolition, and Reconstruction.

And finally, Jacqueline Jones and Henry Wiencek take us beyond emancipation to segregation in the South with a Jim Crow: A Reading List.

FDR did not end segregation in the military, but at the eleventh hour he ordered a ban on racial inequality in defense jobs. And yet the order only addressed wartime circumstances; the Fair Employment Practices Committee he established lasted only until the end of the war.

FDR did not end segregation in the military, but at the eleventh hour he ordered a ban on racial inequality in defense jobs. And yet the order only addressed wartime circumstances; the Fair Employment Practices Committee he established lasted only until the end of the war.