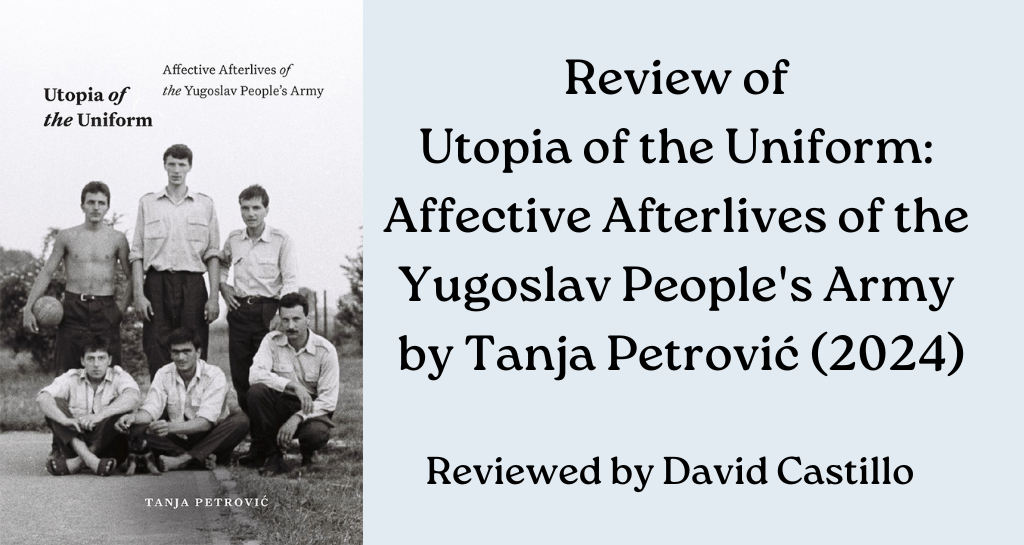

Utopia of the Uniform is a powerful book that challenges historians to broaden their approach to the archive and their sources. It asks how affect and feeling can add nuance to our study of the past, significant historical shifts, and the future. When we met for the first time, Tanja Petrović signed my copy with the note, “To David, for all the stories and feelings he will bring to us from the Yugoslav men”. It stuck with me for some time as I wondered what that word, feeling, meant in that context. It confused me as a historian because I had not really been trained to analyze feelings rather than historical fact. However, after reading Utopia of the Uniform I am left with a sense of wonder in seeing how the author showcased the affective afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army and how she skillfully wove a web that connected periods of time that have traditionally been shattered in post-conflict discourse.

To what degree is nostalgia useful for a society torn asunder by catastrophe? Perhaps a nostalgia that gazes fondly to a period prior to catastrophe might serve as a metaphorical balm, one that eases the lingering pain for the survivors of violence. Or perhaps it could serve as a temporary escape from a grim reality in which contemporary life is contrasted against life in the past, against the ‘better times’. But where does this nostalgic path lead if not to simple daydreaming? Is it capable of inspiring positive change? Tanja Petrović strives to change how scholarly discourse interacts with nostalgia in her 2024 book, Utopia of the Uniform: Affective Afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army.

Petrović views nostalgia as an ineffectual tool of historical analysis and seeks to craft a new frame of reference for temporal progression. As such, she encourages a more nuanced investigation of historical processes and actors in both post-socialist and post-conflict societies. Utopia of the Uniform guides the reader through a nontraditional archive of felt and affective history to showcase how shared memories, photographs, and friendships continue to influence and affect the lived experience of individuals and collectives in the lands that now make up the former Yugoslavia.

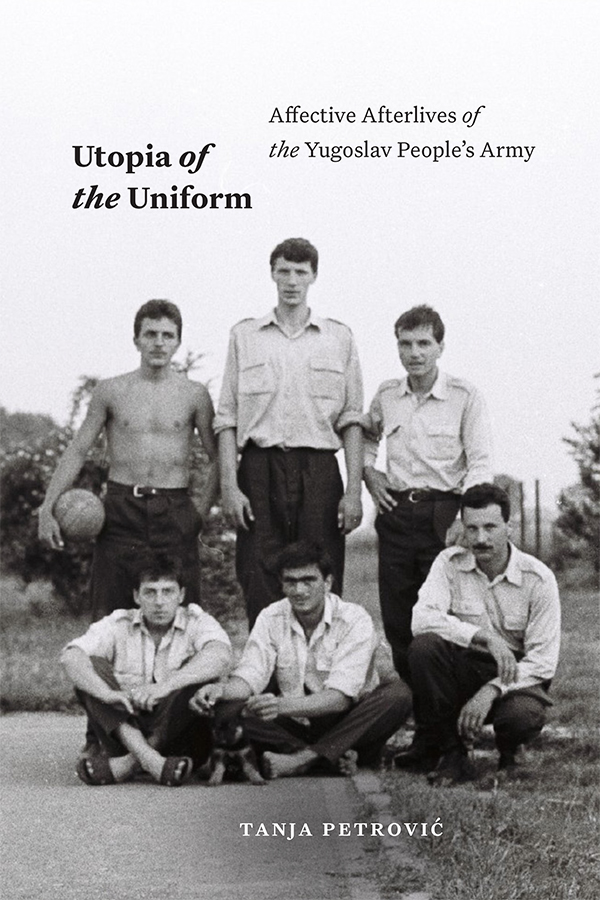

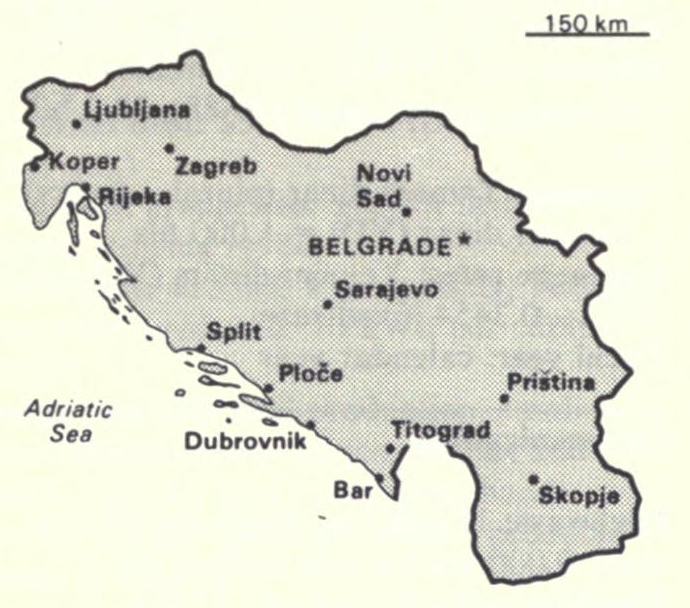

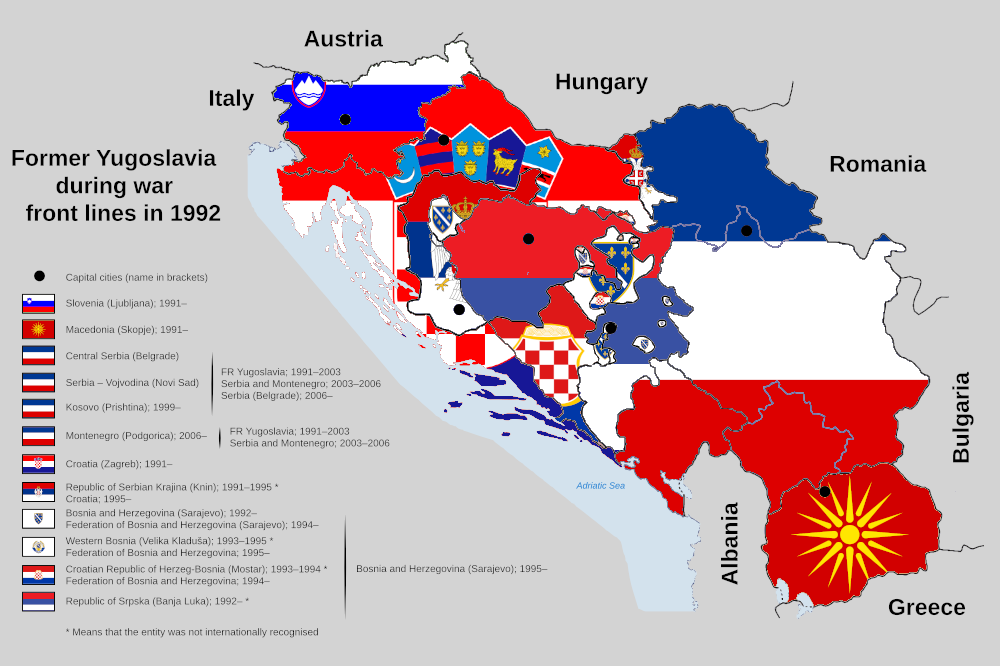

To accomplish this, the author foregrounds her study in the past and present lives of male Yugoslav conscripted soldiers. By analyzing a rich archive of personal narratives, interviews, soldiers’ photography, as well as other forms of artistic and documentary expression, she claims that this archive of felt and affective history inherently possesses its own agency; an agency that Petrović argues is capable of dismantling the limitations of hegemonic ethnic binaries that politicians exploit to keep a grip on power. It is these limitations that have kept the region of the former Yugoslavia and its history wrapped “in an ethnic straightjacket” (p. 178) by binding it to the traumatic destruction of the 1990s. A time period when the fall of state socialism coincided with the rise of nationalist politicians into power (such as Serbia’s Slobodan Milošević and Croatia’s Franjo Tuđman). This shift saw warmongering nationalism call for a dramatic reorientation of society that violently bifurcated Yugoslavia’s rich ethnic and religious diversity practically at every level. By the end of the decade the wars in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo would kill hundreds of thousands, displace millions, and destroy the social and physical infrastructure of the country. Petrović tells us that this profound pain created limiting ethnic binaries that keep this region chained to a destructive past.

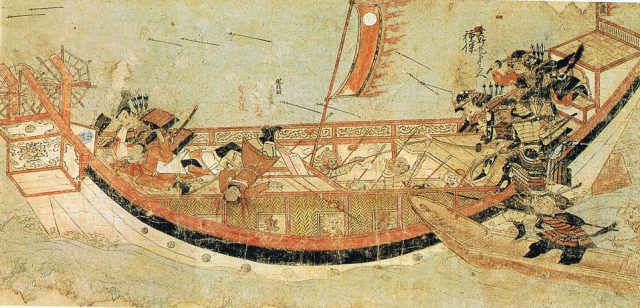

Source: Wikimedia Commons

That past, however, did not begin at the end of the 20th century. Petrović argues that the ideological motivations found within Yugoslav socialism and the way its distinctive federal system was structured allowed for the potential of a utopian perspective. The Yugoslav socialist project after World War II could be seen as unique because of the Yugoslav Partisans’ National Liberation Struggle and their self-led victory over fascist occupation. A new understanding of Yugoslavism that “acknowledged and approved enduring separate nationhoods and sought federal and other devices for a multinational state of related peoples with shared interests and aspirations” (p. 23) emerged after the war. As a result of the mass intercommunal and ethnicized violence of World War II, the new Yugoslav movement made Brotherhood and Unity (Bratstvo i jedinstvo) one of its defining pillars of legitimacy. Thus, a system that sought peace and cooperation among Croats, Serbs, Bosnian Muslims, Kosovar Albanians, Slovenians, Macedonians, and others. The JNA and the accompanying mandatory universal male conscription was a key piece of the unifying project to create Yugoslavs.

The story that Tanja Petrović tells across the book’s nine chapters (including one interlude and an epilogue) is situated along temporal lines that are not limited to narrow linear boundaries. Her narrative examines how forces of the past interacted with each other along a trajectory that moved toward an ideal future, a future that historical actors dreamt would come to fruition. However, as a result of the catastrophic violence and destruction seen in the 1990s during the Yugoslav Wars of Succession, those hopes or utopian ideals and the temporal continuum upon which they progressed was shattered. Therefore, ideal futures that were not only possible but imminent were lost forever, while this rupture forced the former soldiers and their loved ones in Petrović’s study to be left adrift (during the period she coins as the ‘event-aftermath’) in a hostile world where arbitrary ethnic or religious affiliation determines life or death, belonging or ostracization, or prosperity or neglect.

Source: Wikimedia Commons (L), Wikimedia Commons (R)

Even three decades after the wars’ end this rupture still dictates how life in what was once Yugoslavia is lived and perceived. Petrović argues that the citizens of the states that emerged out of the the corpse of the Socialist Federal Republic (SFR) of Yugoslavia (the republics include Slovenia, Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Kosovo) live in neo-fascistic and highly ethnicized societies. Within this post-war world people face a grim present, one in which continuous governmental neglect for peoples’ livelihoods, a general disregard for their safety, and rampant corruption offers no hope for a better future. The author centers an unlikely hero in her story to serve as a utopia of hopeful thought forged in the past and lived in the present: the institution of the Yugoslav Peoples’ Army (JNA) and universal conscription of Yugoslav males for one year of military service. Utopia of the Uniform brings forth a potent contribution in that it is paradoxically within the enclosed barbed-wired bases of one of the most strict, disciplined, and conservative institutions resistant to change in SFR Yugoslavia where utopia could be found.

The bases where these soldiers served became key locations for a utopia, not necessarily because life there was perfect; in fact, Petrović discusses throughout her work that many young men felt that the army was robbing them of a year of their youth when the world was at their feet. The idea of going to someplace far away from your home, a base that was isolated from urban centers, to be molded into a good soldier with domineering discipline constantly watching your every move understandably was a source of frustration for many young Yugoslav conscripts. However, the early foundational leadership of the JNA in the postwar era intentionally designed this feature of the military in order to take Yugoslavs from all different ethnic, religious, social, and educational backgrounds and send them to serve somewhere far away from the region in which they were raised. This had the significant effect of intermingling the whole male population with people who might have been different, thus institutionally reinforcing the idea of Brotherhood and Unity in the country’s fighting force. It was in these bases where JNA soldiers forged bonds, memories, and deep friendships with their comrades in arms that would last a lifetime, especially forging strong ties with people of different ethnicities.

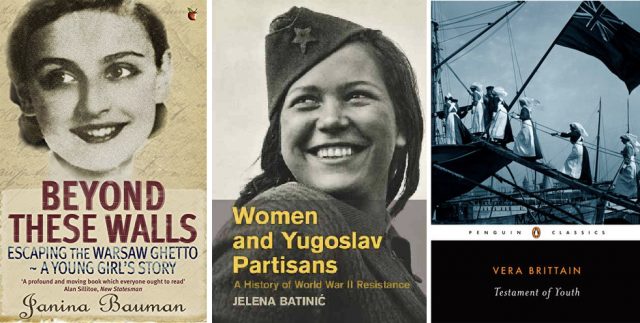

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Petrović utilizes the affective feeling of these soldiers to shatter the restrictive ethnic binary that has held the Ex-Yugoslav region in a chokehold since the 1990s. Through her gripping narrative that bridges Yugoslav times, the rupture of violence, and the eventual event-aftermath, the author colors significant nuance and elaboration into the picture of the (post)socialist and post-conflict society. Utopia of the Uniform demonstrates that the friendships and positive remembrance of former JNA soldiers’ time in military service take on what the author defines as an ‘affective afterlife,’ that is a phenomenon that lives on inspiring happiness, hope, or a fondness in the present despite unimaginable trauma. Additionally, Petrović significantly diversifies and debunks the dominating ethnic narratives that local politicians have hijacked to dictate that ethnic homogenization is the only viable path forward for the successor states.

Utopia of the Uniform demonstrates that the desires of good will and the strong friendship between soldiers of one background to their army buddies of another ethnic background refute the divisive propaganda that stubbornly lives on from the 1990s. The book articulates how the unique context of Yugoslav socialism and the philosophy of Workers’ Self-Management created an “infrastructure for feelings,” or a new social organization that “makes possible responsible decision-making under conditions of interdependency, mutual social responsibility, and solidarity, and that leads to the liberation of individuals.” (p. 189) Petrović argues that this system, despite its flaws, provided space for people to create their own dreams of utopia of the future. This utopia, found in the past within JNA bases across what used to be Yugoslavia, possesses an affective afterlife for the people who survived the 1990s and still offers them happiness, fond remembrance, and even a glimpse of hope for the future.

David Castillo is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, focusing on the former communist Yugoslavia and its successor states. His research explores the links between inter-communal violence, toxic masculinity, gender dynamics, propaganda, and mass manipulation. With academic foundations from the University of Texas at El Paso and Indiana University, David combines cultural history with international politics. Drawing from his experience in the region, he aims to compare post-Yugoslav masculinity shaped by the 1990s wars with Chicano/a/e ‘Machismo’ in Mexican-American borderlands, investigating how violence becomes integral to both identities.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.