Interview by Aragorn Storm Miller

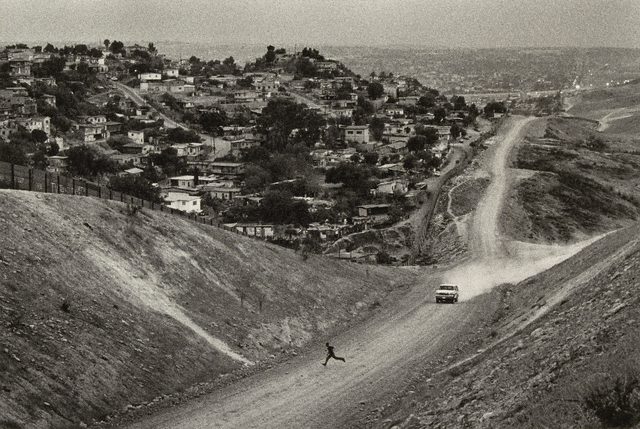

In the third installation of our series, “Making History,” Aragorn Storm Miller speaks with Christina Salinas about her experience as a graduate student in history at the University of Texas at Austin. In the interview, Christina tells us about her childhood spent living near the Texas-Mexico border, the long history of the Texas Border Patrol, and how her research interests have evolved over the course of her undergraduate and graduate career at the University of Texas.

Christina Salinas is a PhD candidate in the history department at UT Austin. Her dissertation explores social relations forged on the ground between agricultural growers, workers, and officials from the U.S. and Mexico, and their impact on shifting national approaches to border enforcement and Mexican migration during the 1940s. She argues that, although border control policies have rested within the bounds of federal authority, it was the interconnection between federal power and local geographies of culture and history that inhabited these policies and gave them meaning.

You may also like:

The inaugural episode of “Making History,” which features an interview with UT history graduate student – and author! – Christopher Heaney.

The second episode of “Making History,” featuring an interview with seventeenth-century Caribbean scholar Jessica Wolcott Luther.

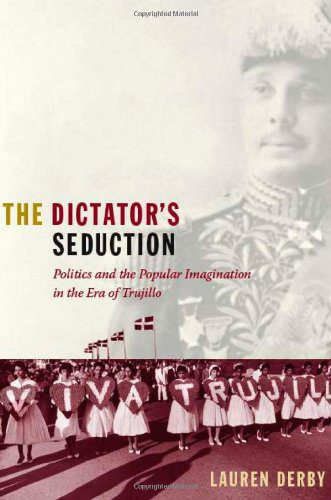

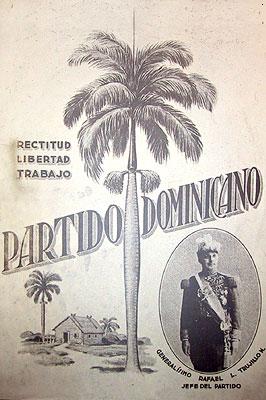

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

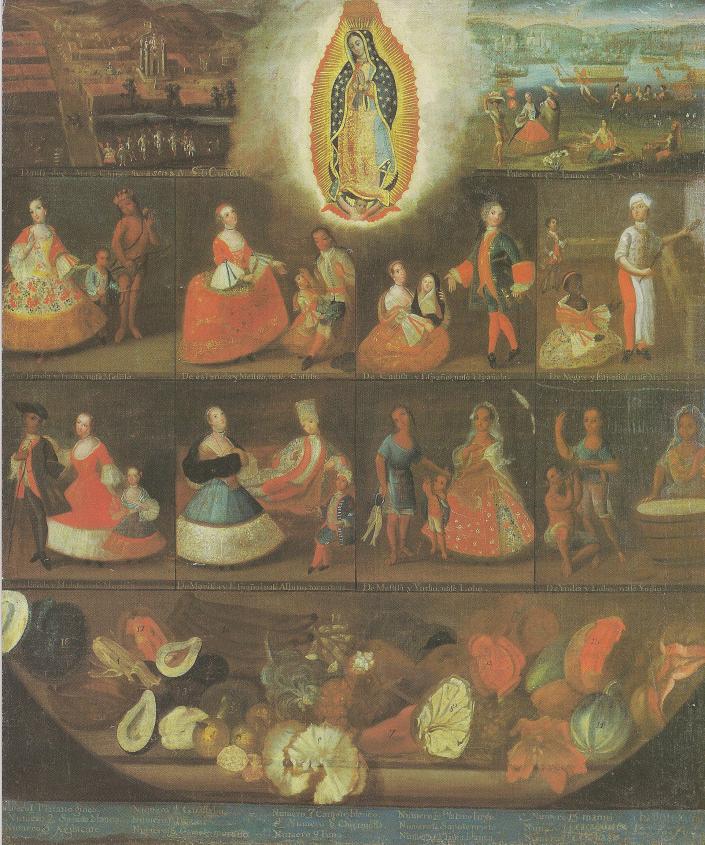

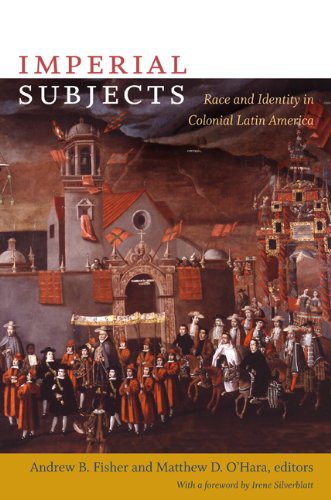

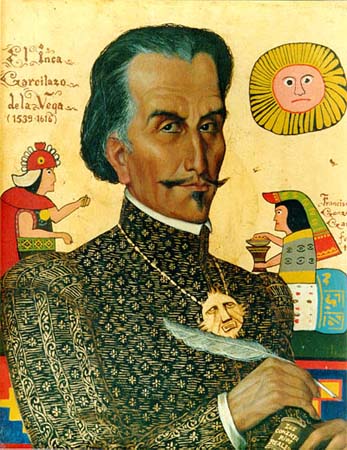

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

The book, by Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, follows the history of Latin America and the Caribbean through a perilous centuries-long struggle against poverty and those imperial powers whose unabashed exploitation ensure its steady existence. For Galeano, Latin America is poor precisely because it is so rich.

The book, by Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, follows the history of Latin America and the Caribbean through a perilous centuries-long struggle against poverty and those imperial powers whose unabashed exploitation ensure its steady existence. For Galeano, Latin America is poor precisely because it is so rich.

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.