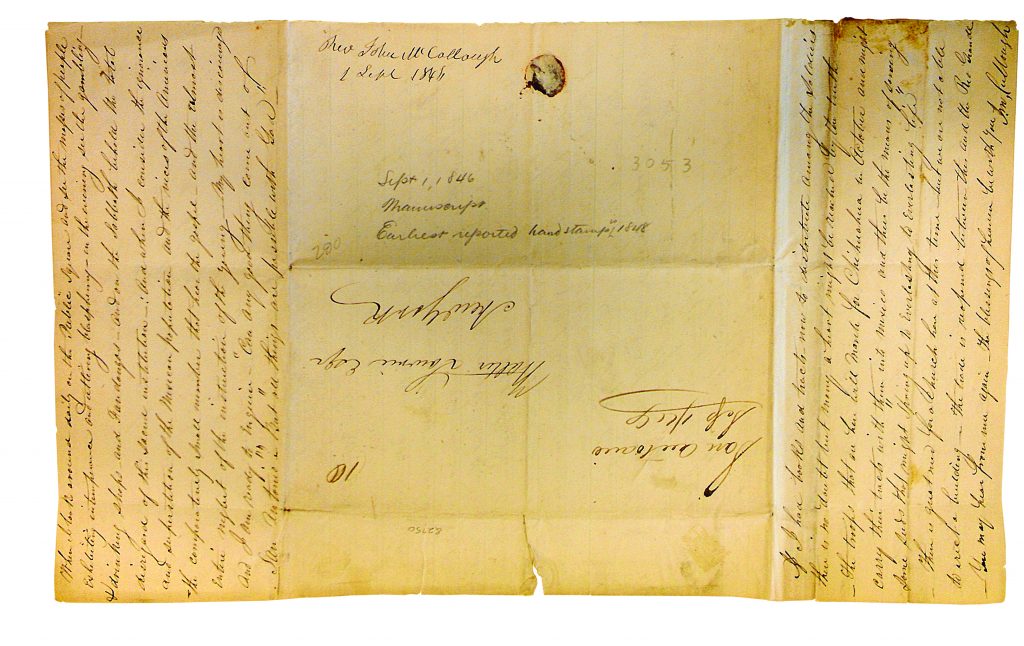

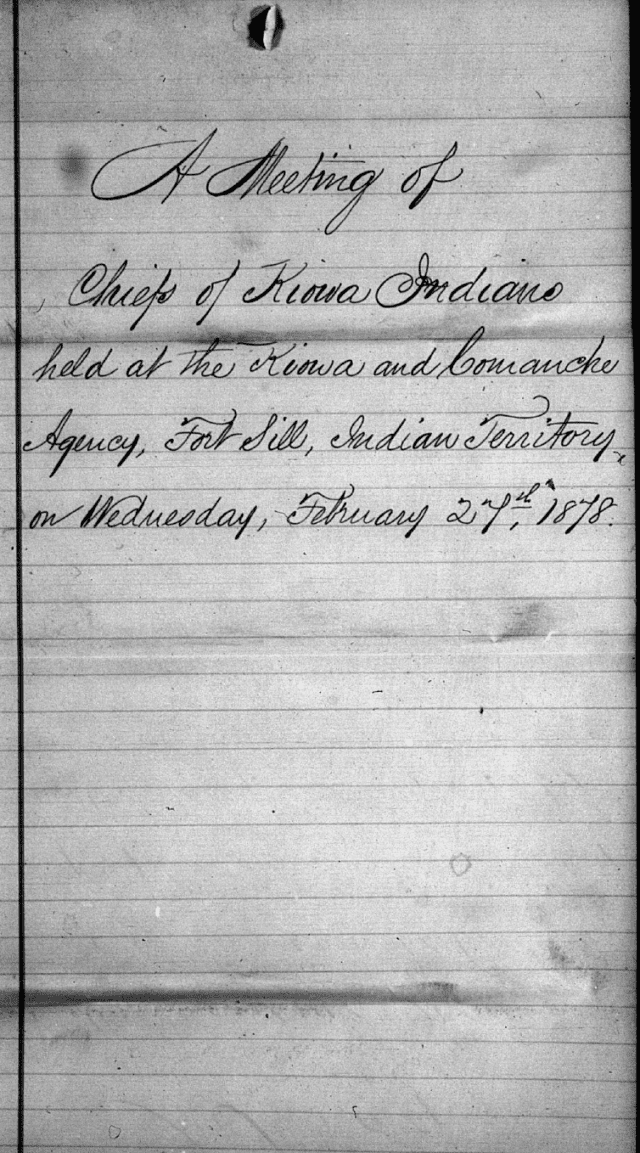

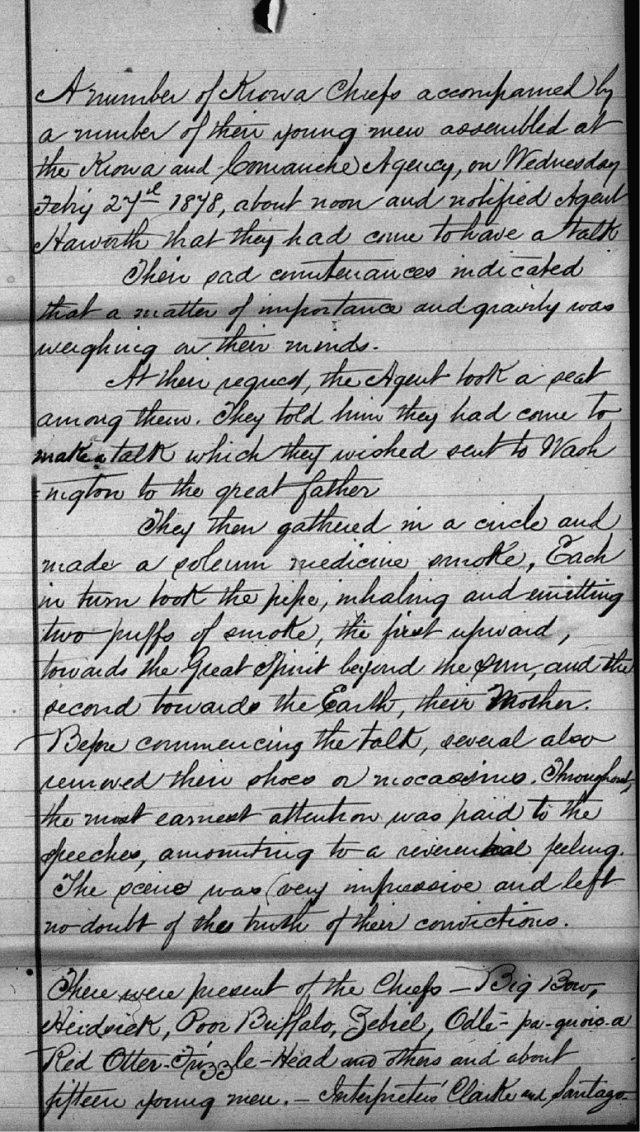

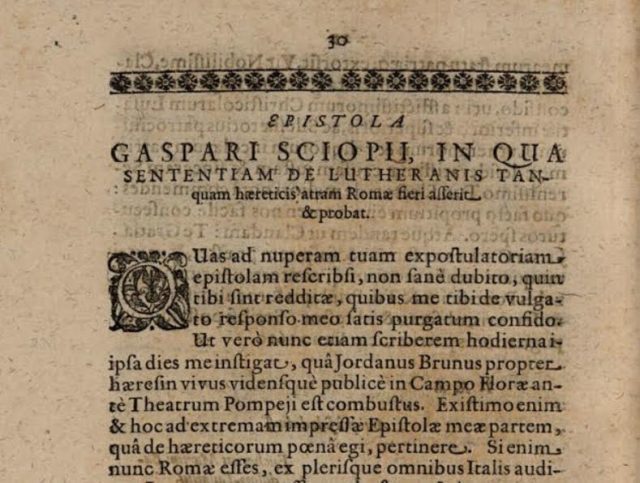

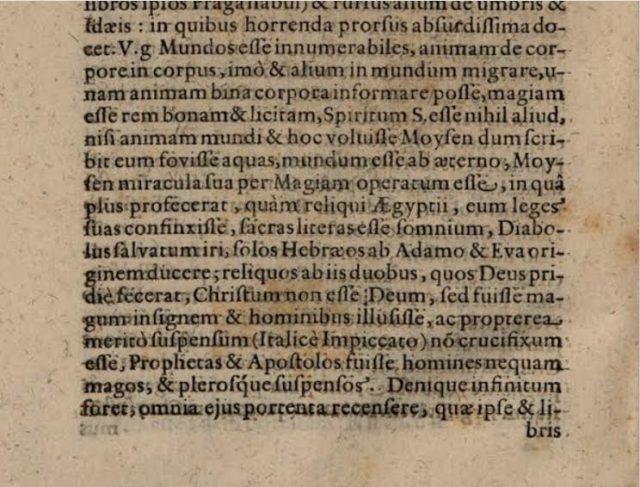

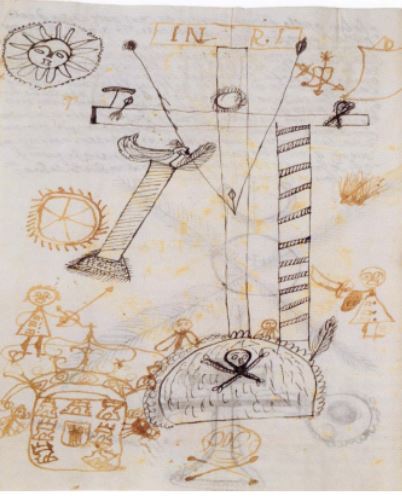

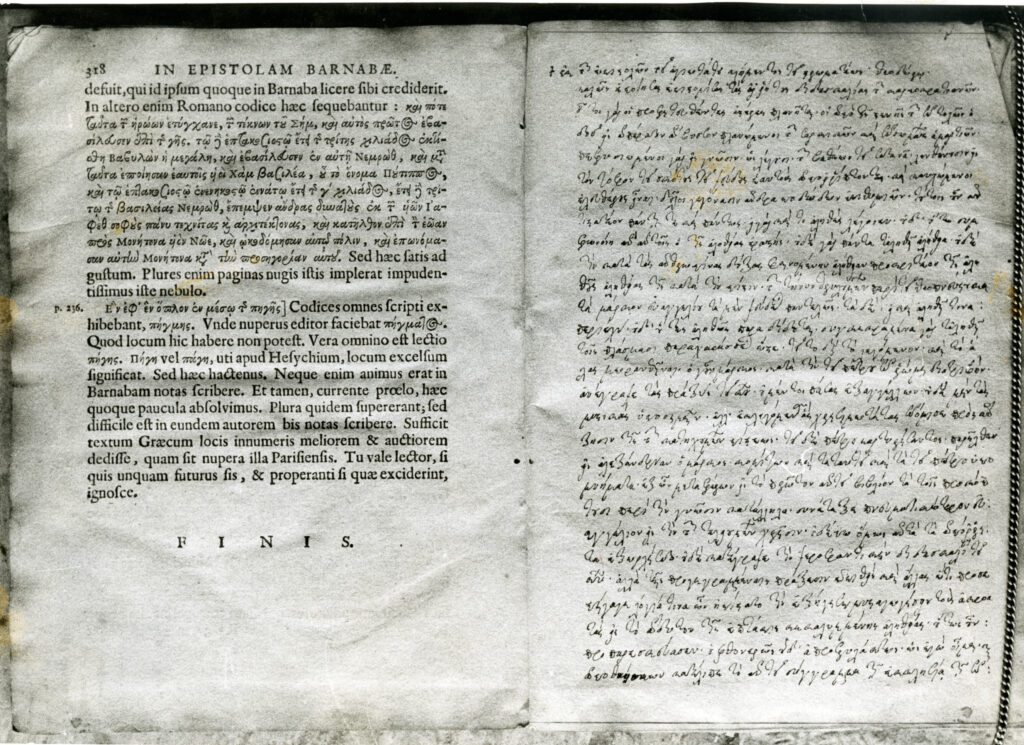

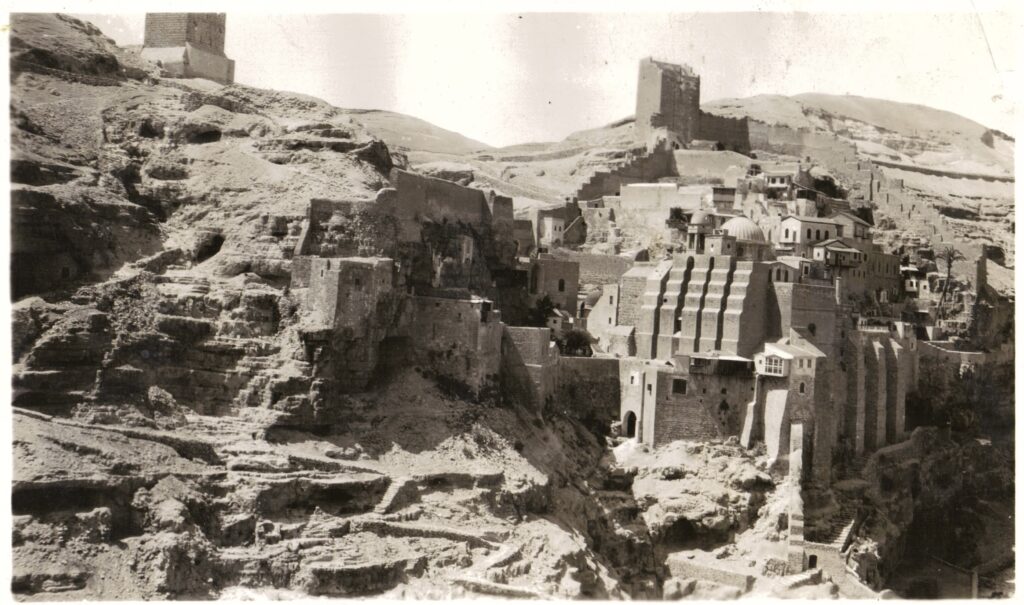

In 1958, an American biblical scholar named Morton Smith was inspecting the book and manuscript collections of Mar Saba, a 1500-year-old monastery in the Judean wilderness. While leafing through a 17th-century printed book Smith discovered something unexpected–a note in Greek written on the blank pages at the back of the book. At the start of the note was a cross, a clue that a monk may have written it. The note purported to be a letter written by an important early Christian leader, Clement of Alexandria, along with quotes from a secret version of Mark’s Gospel. Smith soon realized that the contents of this letter and the secret Gospel were so shocking that, if true, they could call into question the traditional image of Jesus found in the gospels.

In the letter, Clement reveals that the version of the Gospel of Mark found in the New Testament was only a first, incomplete draft of the Gospel. Clement claims that after the death of the Apostle Peter, his assistant Mark traveled to Alexandria in Egypt, where he wrote an expanded version of his Gospel that contained secret teachings for spiritually advanced Christians. But this Secret Gospel of Mark, Clement says, eventually fell into the hands of a group of hedonistic Christian heretics who believed that experiencing carnal pleasures would lead to salvation. Known as the Carpocratians, these heretics rewrote parts of the Secret Gospel of Mark so that it could lend scriptural support to their sexual practices.

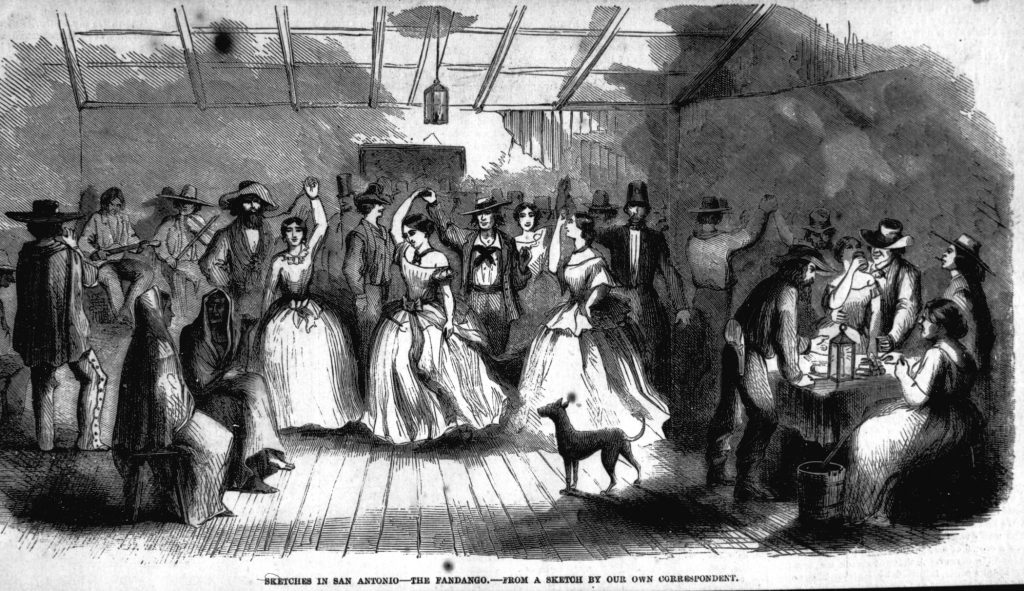

A Christian named Theodore, to whom Clement writes, is anxious to know whether stories about Jesus that the Carpocratians have told him are really part of the Secret Gospel. In response, Clement quotes a passage from the “real” Secret Gospel, a story about Jesus raising a young man from the dead. When he comes back to life, the youth looks at Jesus, loves him, and begs Jesus to stay with him. The youth is rich and has his own house, where Jesus stays for six days. Finally, instructed by Jesus, the youth comes to him at night, naked except for a linen sheet over his body, and Jesus teaches him—as the Secret Gospel puts it—“the mysteries of the Kingdom of God.” Despite its suggestive content, Clement tells Theodore that the Carpocratian heretics have wrongly interpreted this story sexually, adding phrases like “naked man with naked man” to their corrupted version of the Secret Gospel. Clement is about to explain to Theodore what this enigmatic story about Jesus really means . . . but then the letter breaks off.

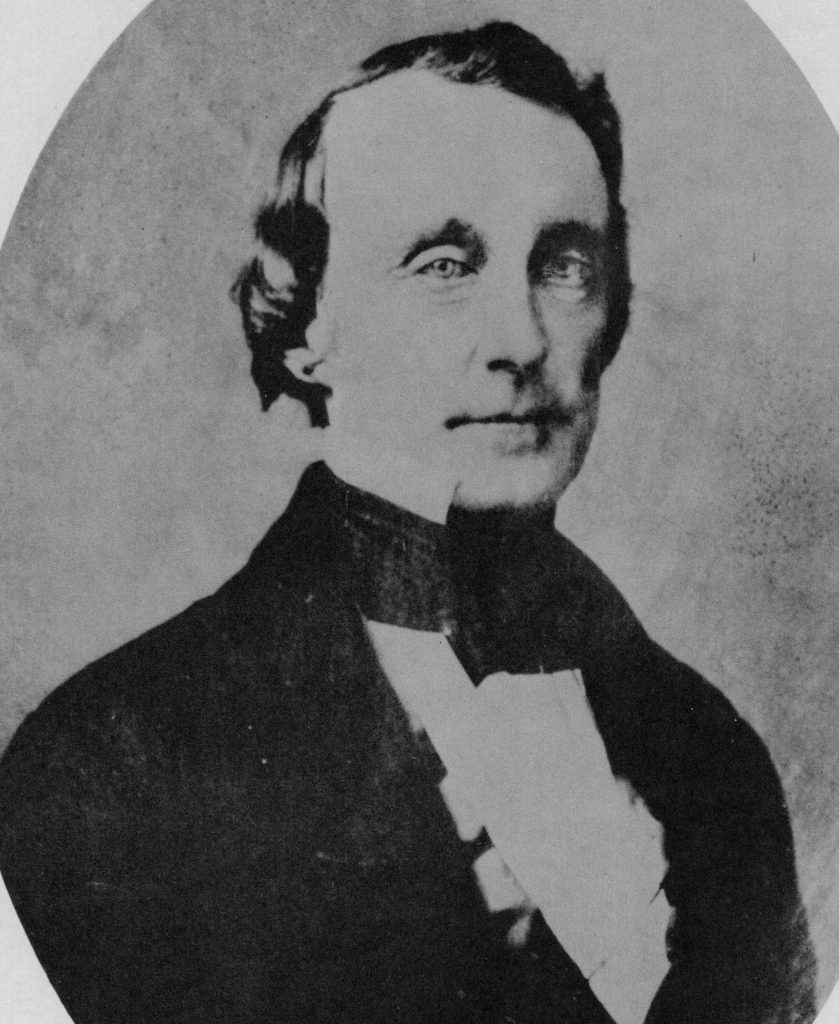

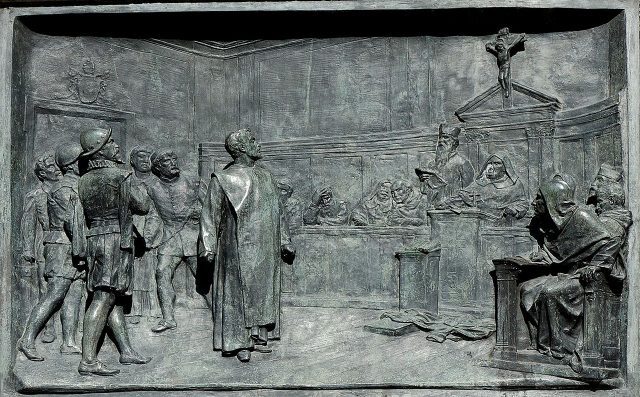

Morton Smith soon realized the enormity of his discovery, and after taking black and white photographs of the handwritten pages, he put the book back where he found it in the monastery. Two years later, he announced the discovery of the letter of Clement to Theodore concerning the Secret Gospel of Mark at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, an announcement that was also heralded on the front page of the New York Times. Ever the provocateur, Smith shocked the straight-laced audience of biblical scholars by quipping that any priest who behaved like Jesus did in this text would find himself in serious trouble with his ecclesiastical superiors. After his announcement, Smith then devoted years trying to make sense of the letter’s contents, and in 1973 he released two books detailing his findings—one technical and academic, and the other designed for a general audience.

Smith did not believe, as Clement claimed in the letter, that the Secret Gospel was an expanded version of the Gospel of Mark written by the same author—namely, Mark the Evangelist. But because the story of the raising of the young man resembled the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John (chapter 11) and the story of the rich young man in the Gospel of Mark (chapter 10), Smith believed that the Secret Gospel preserved a very ancient story that both Mark and John used in their Gospels. If he was right, Smith had discovered in the Secret Gospel one of the earliest known stories about Jesus, a narrative that offers us a glimpse of the historical Jesus’ secret teachings and intimate interactions with his closest disciples.

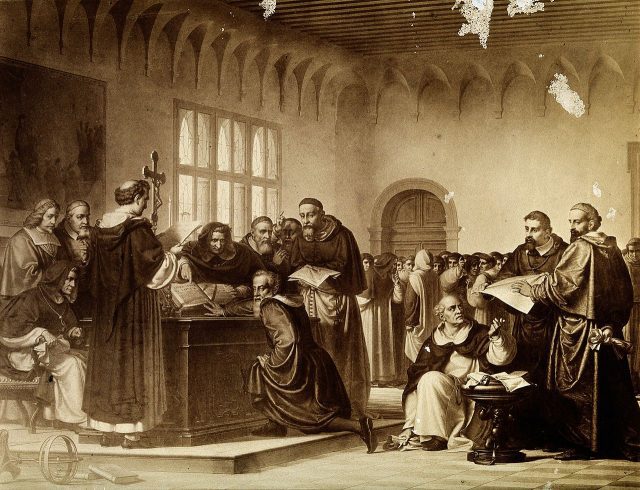

After Smith published his findings in 1973, most scholars believed that Smith had indeed discovered an authentic, ancient letter from Clement of Alexandria, but few thought that the story from the Secret Gospel predated the canonical gospels, as Smith argued. Rather, many scholars preferred to see the Secret Gospel as a second-century apocryphal expansion upon the Gospel of Mark, which was similar to a number of other early apocryphal gospels.

But there were a handful of scholars who were suspicious about the circumstances of the discovery, and suggested that it might be a modern forgery—possibly fabricated by Smith himself. After all, other than Smith’s photographs, there was no proof that this manuscript existed, and Smith’s decision to leave the manuscript in the monastery instead of removing it for safekeeping was second-guessed. Despite allegations of forgery, however, the conventional wisdom among scholars was that Smith’s initially assessment was likely correct.

Yet this conventional wisdom was shattered in 2005 by Stephen Carlson, a patent lawyer who at the time was not a trained biblical scholar. Carlson published a book whose title made his view of Smith’s discovery absolutely clear—The Gospel Hoax: Morton Smith’s Invention of Secret Mark. Carlson alleged not only that forensic analysis of the manuscript showed the presence of a “forger’s tremor” (that is, irregular movements indicating an attempt to imitate a different style of handwriting), but also that Morton Smith had left behind several subtle clues–“breadcrumbs”–in the letter of Clement that revealed him to be the author.

Although scholars who believed that Smith had discovered an authentic writing pushed back against Carlson’s claims, his book led a flurry of other scholars to claim to have found evidence that Smith had forged the manuscript. Some pointed to parallels between Smith’s discovery and the contents of a 1942 novel, The Mystery of Mar Saba; others saw indications that Smith was already interested in the ideas that the Secret Gospel contained before he “discovered” the manuscript; still others alleged that Smith was a gay man, and that he had created a text containing a homoerotic encounter between Jesus and a young man in order to validate his own sexuality.[1]

Many of the arguments that Smith forged the document rely on evidence that is highly circumstantial. Nevertheless, the sheer number of these arguments seems to have created a new conventional wisdom among biblical scholars: that the Secret Gospel of Mark is a modern forgery, and Morton Smith is likely its author. Certainly, there are still scholars who argue that Clement’s letter and the Secret Gospel are genuine ancient writings, but these voices have become increasingly marginalized. At present, scholars can be divided into two broad camps: those who believe that Morton Smith discovered an enormously important ancient writing, and those who believe that he invented this writing himself.

While there is much about Morton Smith’s discovery of Clement’s letter and the Secret Gospel of Mark that remains unclear, we are convinced of two facts that, taken together, render both of the current scholarly opinions about this text inadequate. First, given our extensive experience working with manuscripts, we regard the Greek handwriting style of the manuscript to be so complex and so characteristic of other Greek handwriting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that it would have been impossible for Morton Smith to forge it. Perhaps a master forger whose native tongue was Greek might have been able to create this manuscript, but Smith was not a Greek-speaking master forger.

Second, we are convinced that this letter, even if ancient, was likely not written by the second-century Christian writer, Clement of Alexandria. The real author of the letter probably made use of the writings of Eusebius of Caesarea, a fourth-century Christian historian and biographer. While the true name of the author remains a mystery, it was probably not Clement of Alexandria. So, the writing that Morton Smith discovered was not composed by Clement of Alexandria. Nor was it forged by Smith himself. Neither of the current scholarly opinions about the Secret Gospel of Mark are correct. The truth, we argue, lies somewhere in between.

In our new book, The Secret Gospel of Mark: A Controversial Scholar, a Scandalous Gospel of Jesus, and the Fierce Debate over Its Authenticity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), we offer a new theory about the origins and historical significance of the Secret Gospel of Mark. But we also reveal that the story of the Secret Gospel transcends the document itself, which incidentally is now lost. While the Secret Gospel of Mark can teach us something about Christianity’s distant past, it also exposes the inner workings of a small cadre of biblical scholars tasked with reconstructing that past. In the end the Secret Gospel may have less to say about the historical Jesus than it does about the preoccupations, politics, and rivalries of those who seek to uncover the truth about him.

[1] For a lively back and forth that addresses much of this evidence for Smith’s alleged forgery, see Craig Evans, “Morton Smith and the Secret Gospel of Mark: Exploring the Grounds for Doubt,” 75-100; and Scott Brown and Allan Pantuck, “Craig Evans and the Secret Gospel of Mark: Exploring the Grounds for Doubt,” 101-134; both of which can be found in Tony Burke (ed.) Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery? The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2013).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.