By Tiana Wilson

Many recent studies on chattel slavery in the Atlantic World have decentered the voices of the colonizers in an effort to creatively reimagine the inner lives of Black people, both enslaved and “free.” However, narrating the complex ways race, gender, and sexuality played out in a colonial setting beyond violence has proven difficult due to the brutal, inhumane conditions of enslavement. At the same time, the drastic imbalance of power raises questions about consent within sexual and intimate relationships. While most scholars of slavery have tended to shy away from such a contentious and messy topic, historian Jessica Marie Johnson presents a compelling analysis of how African women and women of African descent used intimacy and kinship to construct and live out freedom in the eighteenth century.

She demonstrates how the legal status of free, manumission from bondage, or escape from slavery did not protect Black women from “colonial masculinities and imperial desires for black flesh” that rendered African women as “lecherous, wicked, and monstrous” (14). Slaveowners, traders, and colonial officials attempted to exploit Black women’s bodies (enslaved or legally free) for labor. In return, Johnson argues, Black women defined freedom on their own terms through the intimate and kinship ties they formed.

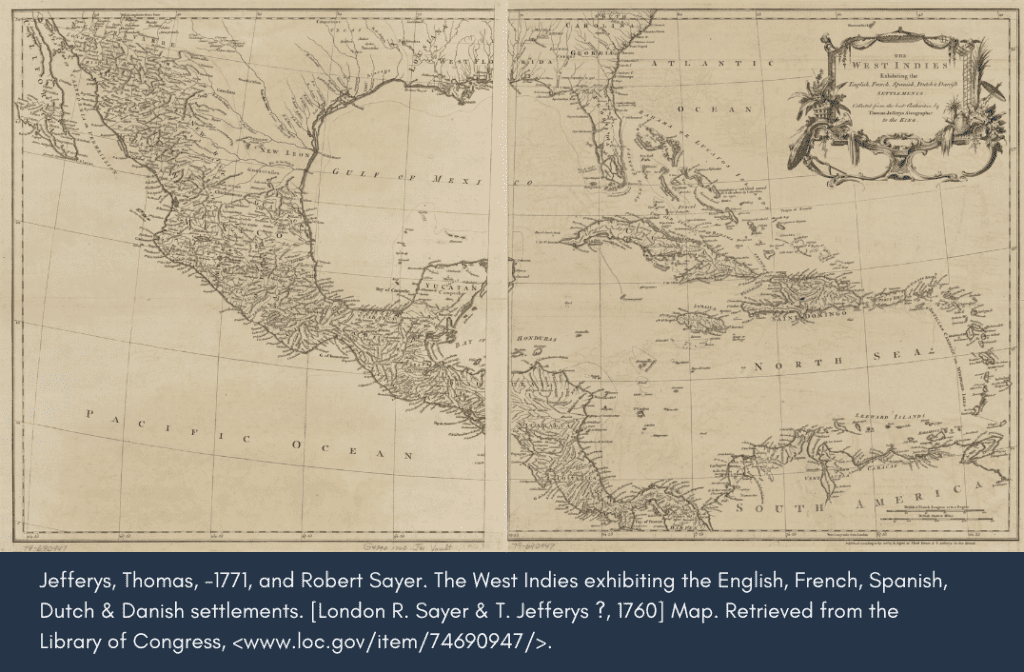

Focusing on Black women in New Orleans, Wicked Flesh takes readers from the coast of Senegal to French Saint-Domingue and from Spanish Cuba to the US Gulf Coast areas in order to tell the varying experiences of Black women across the Atlantic world. Johnson draws on archival material written in multiple languages dispersed across three continents and uses a method that historian Marisa Fuentes describes as “reading along the bias grain” to offer an ethical historical analysis of her texts. Although the majority of sources Johnson utilizes were produced by colonial officials and slaveholding men, this methodology allows Johnson to carefully and innovatively piece together archival fragments, providing readers insight into the everyday intimate lives of Black women during this era. Intimacy, as Johnson explores, encompassed the “corporeal, carnal, quotidian encounters of flesh and fluid” and was the very thing that tied Black women to white and Black men. It was through these connections that women of African descent simultaneously endured violence and resisted colonial agendas. Wicked Flesh seriously consider the ways Black women fostered hospitable and pleasurable spaces on both sides of the Atlantic.

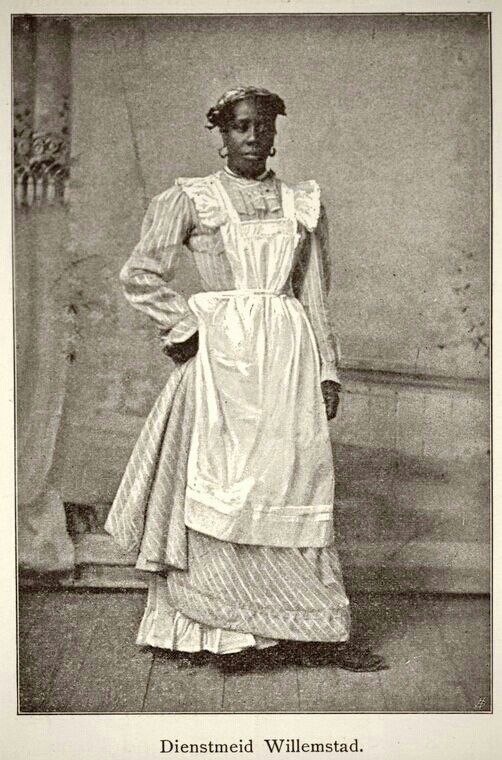

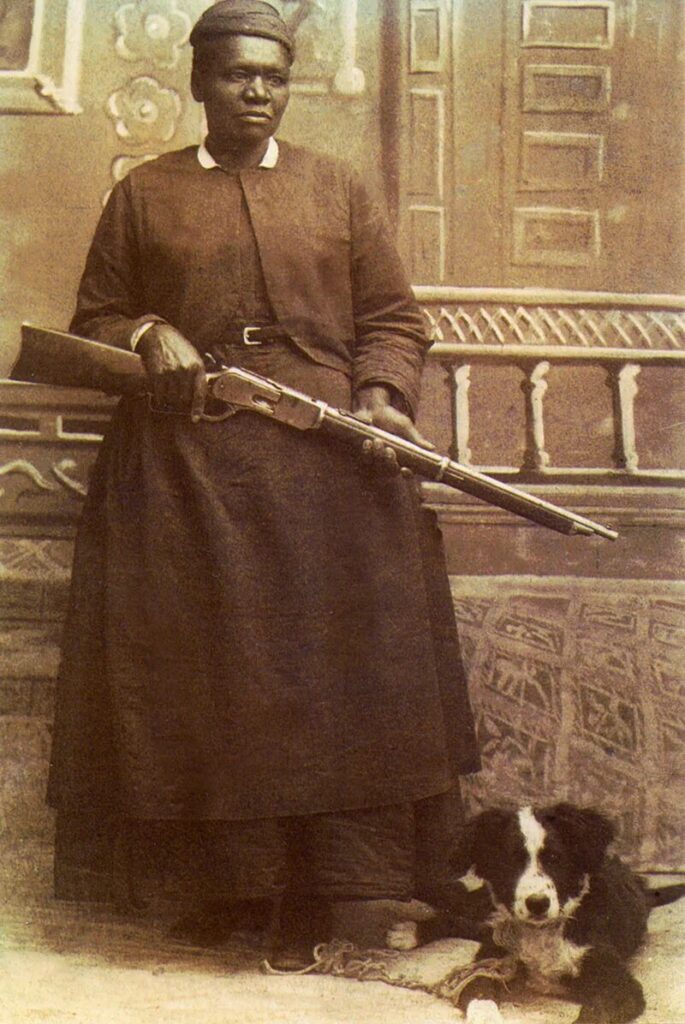

Johnson begins her narrative in West Africa between the geographical region of the Senegal River (north) and the Gambia River (south), also known as Senegambia. Senegal’s Atlantic coast saw Portuguese-Dutch-French-Wolof trade alliances and their struggle for power, but by 1659, the French drove out the Dutch from the northern area and founded the comptoir (administrative outpost of Saint-Louis. It is in this locale, comptoir, that Johnson introduces readers to free African women like Seignora Catti, Anne Gusban, and Marie Baude, who all actively engaged in networks with European and African men.

Throughout chapters one and two, Johnson demonstrates the different ways free African women cultivated freedom in efforts to seek safety and security. This included participating in grand gestures of hospitality for French officials or marring European men, but rejecting their Catholic practices. These practices impacted three groups, free African women who has intimate ties with European and African men, captifs du case (enslaved people who belonged to comptoir residents), and Africans forced onboard of slaved ships set to travel to the Americas. Chapter three examines the latter, including Black women’s and girl’s horrific experiences on the long middle passage and how this forced migration produced a “predatory network of exchanges” that attempted to “dismantle their womanhood, girlhood, and humanity” (123).

Chapters four and five shifts to the Gulf Coast region and encourages readers to reconceptualize the price of manumission for people of African descent that extended beyond the material world. Through the lives of figures like Suzanne, the wife of a New Orleans “negro executioner,” Johnson further illustrates just how bound Black women’s freedom was to their intimate relations and kinship ties with men in power who were acting on behalf of the French colonial regime. When Suzanne’s husband, Louis Congo, initially entered in a contractual obligation with slaveowners or Company officials, he requested freedom for Suzanne too. However, French colonists rejected his demand and instead, only allowed Suzanne to live with her husband, if Louis agreed to grant the Company full use of his wife when the Company needed her. While one scholar may read this account as an example of a Black woman gaining her freedom through her husband’s occupation, Johnson critically assess Suzanne’s lack of control over her own body and movement.

Diving deeper into the intricate ways women of African descent navigated French colonial power in New Orleans, Johnson’s fifth chapter follows girls like Charlotte, the daughter of a French colonial officer, who demanded manumission for herself. It is in this section that Johnson introduces the concept of “black femme freedom” that “points to the deeply feminine, feminized, and femme practices of freedom engaged in by women and girls of African descent” (260). Scholars of Black and other women of color feminists use the term “femme” to describe a queer sexual identity that is gendered in performances of femininity. Johnson finds this term productive in the context of eighteenth-century New Orleans, because strands of resistive femininity and intimacy between women was present during this time. Black femme freedom details a type of liberation that went beyond masculine and imperial desires. It describes the importance of reading Black women’s intimate decisions to privilege themselves and each other in a world that violently privileged the position of slaveowners and husbands. An example of this Black femme freedom lies within Black women’s efforts to create spaces for pleasure, spirit, and celebration against French and later Spanish censorship of their behaviors. This included hosting night markets and wearing headwraps. The last chapter explores the shift in colonial powers and how free women of African descent used this change to claim kinship ties through registration of their wills and testaments.

Wicked Flesh is a well-researched, beautifully written text that is an essential read for anyone interested in the intersections between Slavery, Gender, and Sexuality. Following in the tradition of historians like Stephanie Camp, Jennifer Morgan, and Marisa Fuentes, Johnson’s work is a superb addition to these groups of scholars who are shifting the field of Atlantic History to critically engage with definitions of freedom for enslaved and legally free women of African descent during the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Graduate students including myself can (and likely will) use Johnson’s work as a model for problematizing white colonial sources, while ethically utilizing contemporary theoretical frameworks to imagine and retell the lives of those silenced by institutional archives.

Image credits

Banner image – Ndeté-Yalla, lingeer of Waalo, Gallica, bnf.fr – Réserve DT 549.2 B 67 M Atlas – planche n °5 – Notice n° : FRBNF38495418 – (Illustrations de Esquisses sénégalaises) Image from Wikimedia Commons

TIANA WILSON is a Ph.D. Candidate in the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin.