Recommended by Daina Ramey Berry and Leslie Harris

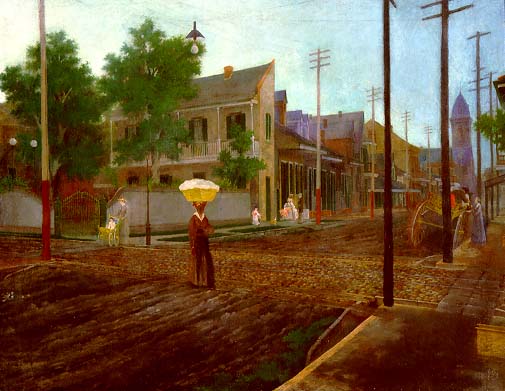

Richard Wade, Slavery in the Cities: The South, 1800-1860. (1967).

This book remains the best one-volume account of urban slavery in the antebellum South. It combines overall trends in urban slavery with detailed accounts of the populations, laws, and economic roles of individual cities. The place to start with investigations of urban slavery in the U.S. South.

Claudia Dale Goldin, Urban Slavery in the American South, 1820-1860: A Quantitative History. (1976).

This comprehensive study of urban slavery argues that the demand for urban slaves increased rather than declined in the 1850s. The author challenges scholars such as Richard Wade by relying on quantitative and traditional sources such as census and probate records.

Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris, eds. Slavery in New York. (2005).

This edited collection accompanied the ground-breaking New-York historical society exhibition of the same name. Leading scholars of New York, slavery and African American history provide a wealth of information on how slavery in New York from 1626 to 1827, and southern slavery after New York ended slavery in 1827, influenced the economy, politics and society of one of the nation’s leading cities.

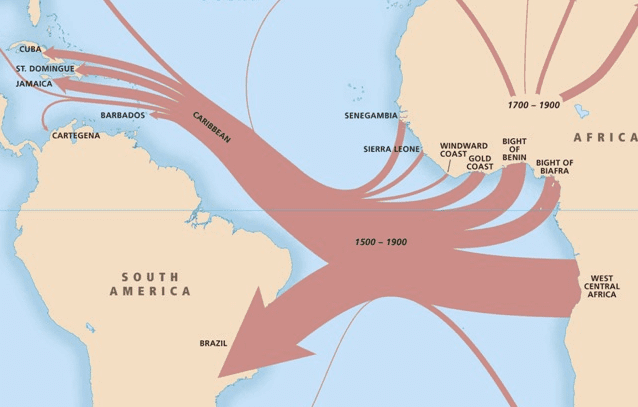

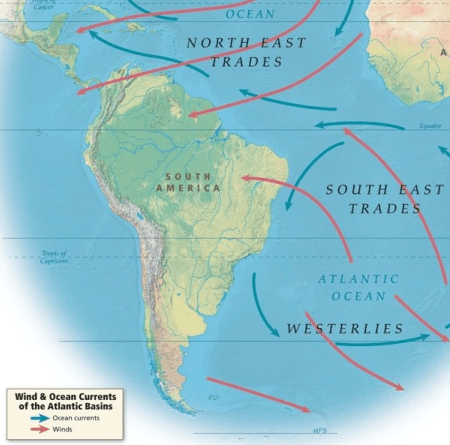

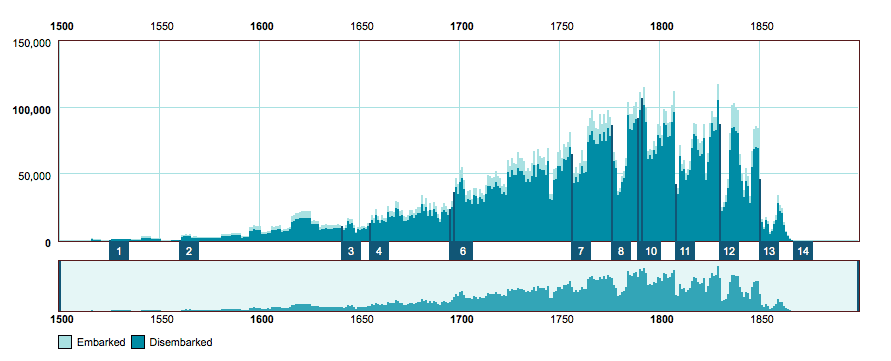

Jorge Canizares-Esguerra, Matt D. Childs and James Sidbury, eds., The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade. (2013).

The essays in this book examine non-U.S. cities and their centrality to the slave trade and slave economies, including locations in Africa, South America Portugal, and the Caribbean.

Seth Rockman, Scraping by: Wage Labor, Slavery and Survival in Early Baltimore. (2009).

By examining the relationship of enslaved and free laborers in the political economy of Baltimore, Rockman challenges us to understand the role of slavery as part of, not distinct from, early capitalist formations. Compelling individual stories of laborers carry the broader arguments about the meaning of labor in one of the most important cities in the antebellum U.S.