THE NEW ARCHIVE (No.2)

Computer and online technologies are enabling historians to do history in a variety of new ways. Archives and libraries all over the world are digitizing their collections, making their documents available to anyone with a computer. Mapping and other kinds of visualization are allowing historians to create new kinds of documents and ask new questions about history. Each week, our Assistant Editors, UT History PhD student, Henry Wiencek and Undergraduate Editorial Intern, Charley Binkow, will introduce our readers to the world’s most interesting new digital documents and projects in THE NEW ARCHIVE.

How did slavery end in America? It’s a deceptively simple question—but it holds a very complicated answer. “Visualizing Emancipation” is a new digital project from the University of Richmond that maps the messy, regionally dispersed and violent process of ending slavery in America.

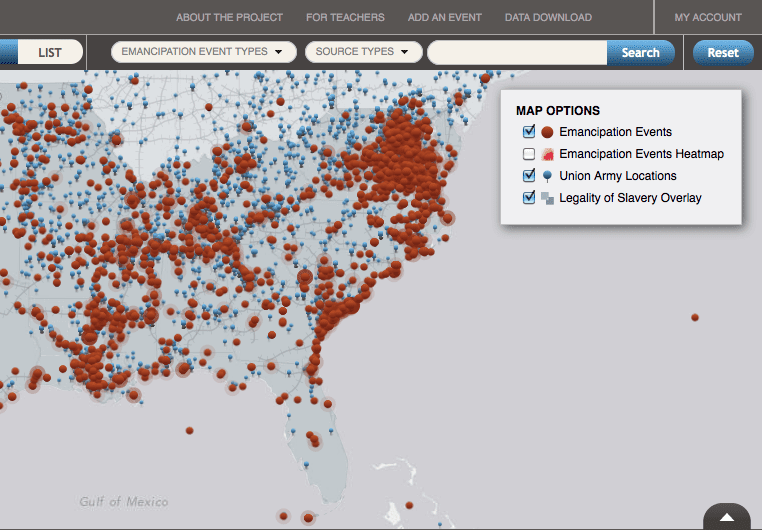

Using a map of the United States, the site visually charts the precise time and place of “emancipation events” that appeared in newspaper accounts, books, personal papers or official records between 1861 and 1865. Click on any of the red dots scattered across the map and you get a small snapshot of emancipation as a historical process: blacks in Culpeper, Virginia assisting Union troops on July 19, 1862; confederate troops forcibly conscripting blacks in Yazoo City, MS on September 27, 1863; an enslaved man named Wm. P. Rucker escaping in Pittsylvania County, VA on October 27, 1863. And alongside the red dots of “emancipation events,” blue dots illustrate the changing positions of Union troops, a clever overlay of social and military history. Move the time frame backwards or forwards and an entirely new set of “events” appears, coordinated spatially with the movements of troops.

This exciting new project aims to be an online resource to educators looking for a unique means of teaching the end of slavery. The site also hosts an impressive archive of more traditional primary documents users can easily access for lesson plans and further reading.

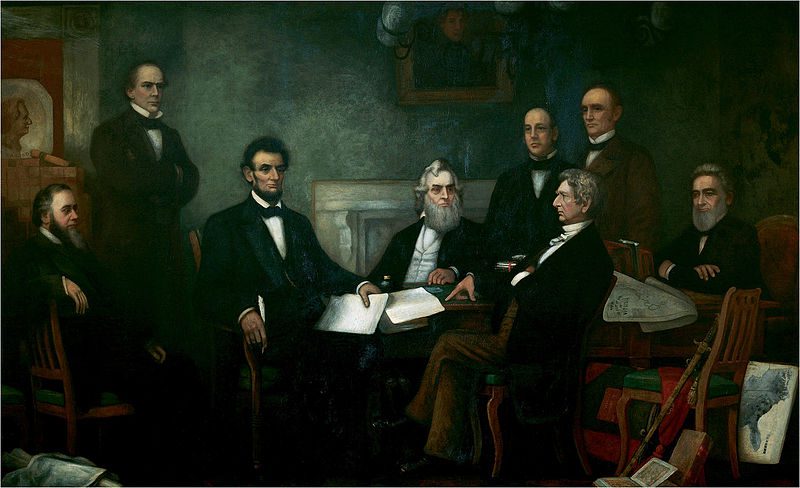

“Visualizing Emancipation” changes the story of emancipation from one singular turning point—Lincoln’s proclamation—to thousands. Its scattered and chaotic map connects small, often seemingly futile, acts of local resistance into a compelling visual depiction of the multiple and diverse acts that marked the end of slavery in America. Moreover, the defeats for rebelling slaves or Union troops that appear here make another crucial point: emancipation was never inevitable—it had to be earned through the blood and sweat of individual soldiers, slaves, freedmen, and countless others. “Visualizing Emancipation” artfully illustrates that and allows us to see their stories in new ways.

And don’t miss Charley Binkow’s piece on a new digital archive dedicated to Ireland’s Easter Rising

Photo Credits:

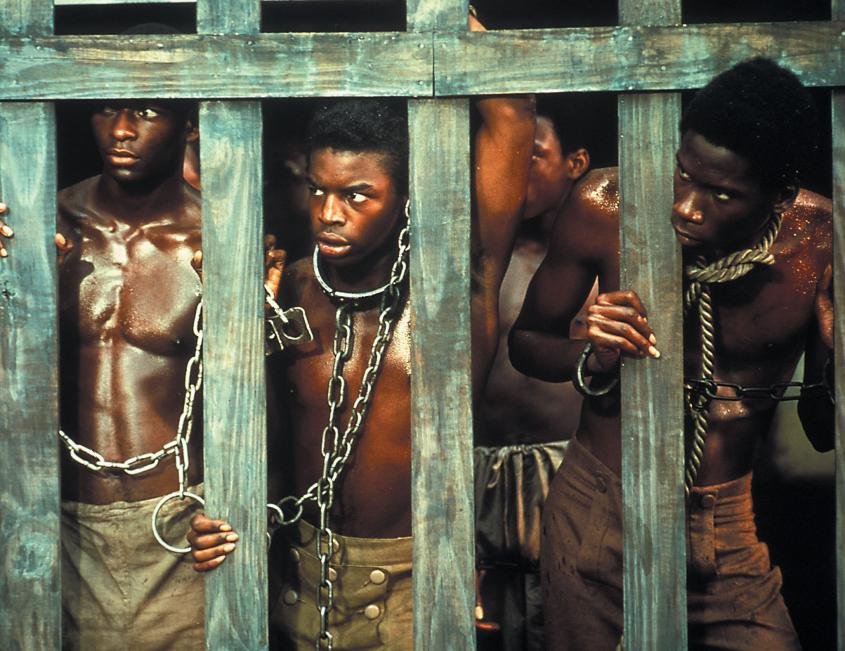

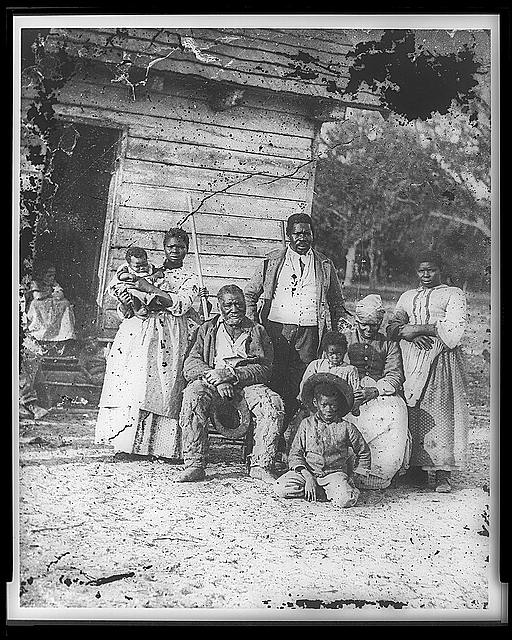

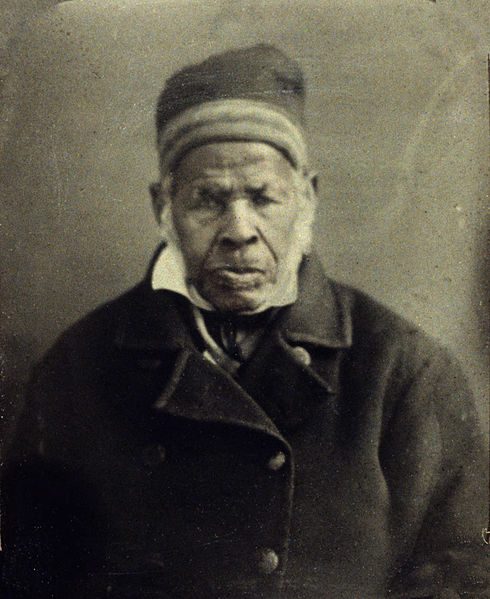

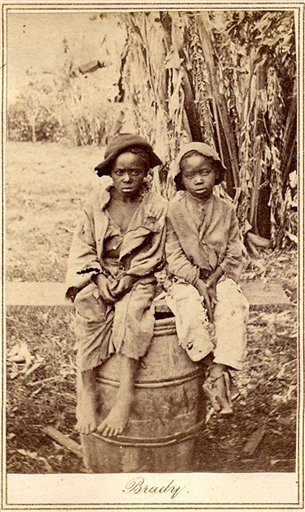

Recently freed slave children, possibly photographed by Matthew Brady, circa 1870 (Image courtesy of AP Photo)

Screen shot of “Visualizing Emancipation”

determined to demystify perhaps the central episode in this nation’s history. Yet, historians have not labored alone.

determined to demystify perhaps the central episode in this nation’s history. Yet, historians have not labored alone.