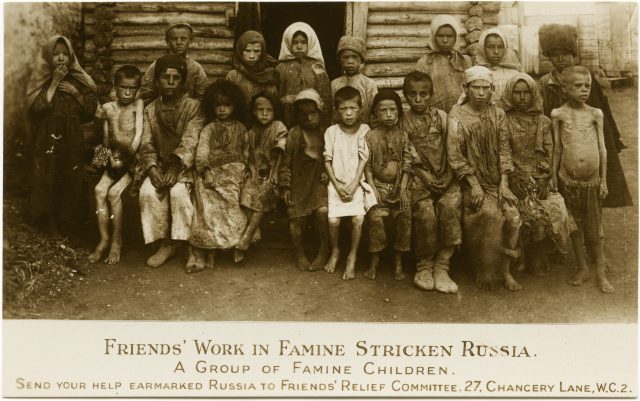

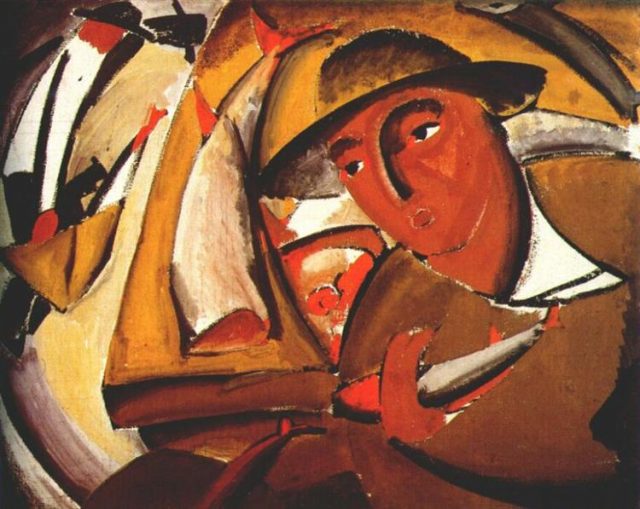

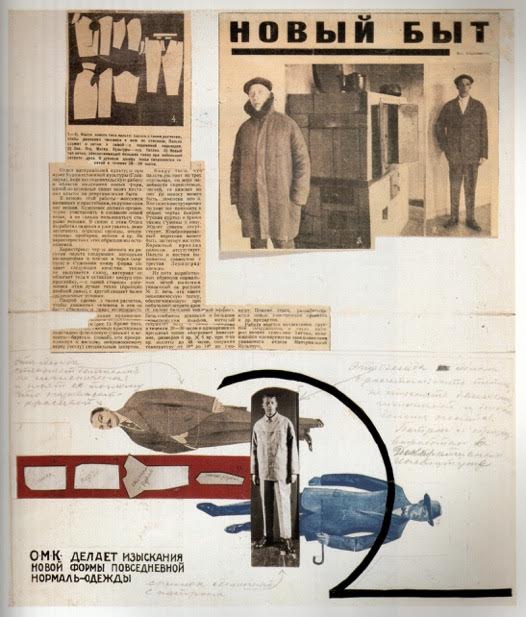

Until quite recently, tales of Americans’ enchantment with the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s were typically told as prelude to their eventual disenchantment: this “liberal narrative” described immature, naïve, utopian idealism replaced by contrition and mature, rational rejection of radical extremism. So it was that I felt embarrassed by the excitement I found myself experiencing when I read descriptions from the time of exciting developments in the “new Russia.” In addition to the Soviet avant garde’s innovations in visual art, theatre, film, and literature, I found repeated emphasis on the special provisions being made for women and children: eliminating the very idea of an “illegitimate” child; radically democratizing education; simplifying divorce; mandating equal pay in the workplace; legalizing and subsidizing abortion; extending pre-natal and maternal welfare provisions; and creating public dining halls, laundries, and nurseries so that domestic duties would not limit women’s professional capacity (yes, these duties were still understood to be women’s).

I felt in my own gut some of the deep attraction that many people in the West experienced amid and following the Russian Revolution. But as a historian, I had incontrovertible proof that the Soviet state, despite every artist it supported, every cool program it put into effect, every effort it made to raise the level of the masses, was at a very fundamental level dehumanizing, repressive, and often violent, all of which became clear to many outsiders fairly early on. I remember telling a colleague that I was interested in exploring and perhaps making sense of all the hopeful rhetoric in the US vis-à-vis the Soviet Union and her warning me that following this path would get me into a whole lot of mishegas, craziness, a Yiddish word that I’ve always figured needs no translation. But the Soviet thing was like an itch I couldn’t keep myself from scratching. I wondered if I could take on this topic, or some piece of it, without seeming to be an apologist for Stalin or denying the facts of history. I had written about left wingers who wrote children’s books during the McCarthy era, which is to say, I had already spent some time thinking about the inherent contradictions within the communist movement.

A few scholars who had come of age after the end of the Cold War were writing about Americans and the Soviet Union in more nuanced ways than had been possible in an earlier era. However, I’d seen very little written specifically about attraction to the “new Russia” on the part of women, particularly independent, educated, and liberated “new women”— this despite the fact that, as the title of a breezy syndicated news article published in 1932 would suggest, “American Girls in Red Russia” were, well, a thing.

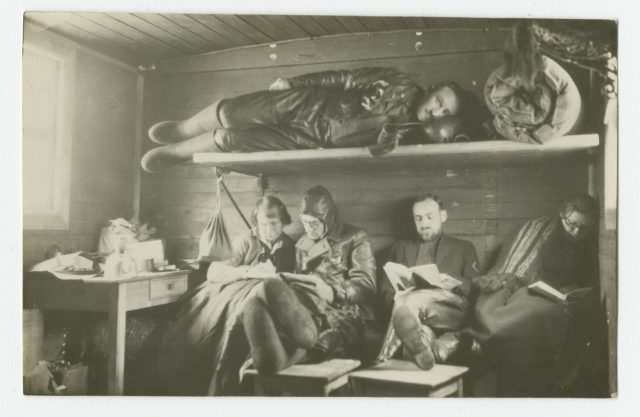

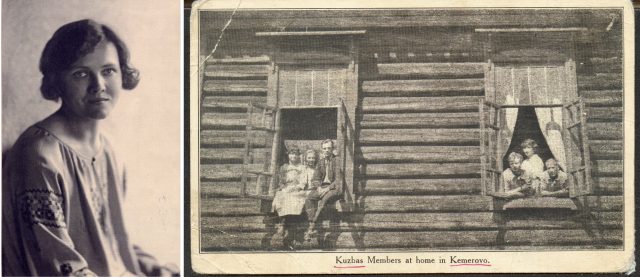

Oddly enough, it was continuing research in children’s literature that finally convinced me to go ahead and write a book about “American Girls in Red Russia,” mishegas and all. In the archives of Ruth Epperson Kennell, who, in the 1930s and 1940s, published a number of books and stories about children in the Soviet Union, I found myself intrigued by Kennell’s own story, especially her years as a “pioneer” in Siberia working on an industrial commune founded by several American Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) in the early 1920s. Seeking release from what Lenin had described as the “household drudgery” that confines women in most societies, Kennell was attracted to the idea of living communally—and also working collectively toward the shared goal of creating a better world. Answering a call from the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia, she and her husband Frank signed a two-year contract, packed up their worldly possessions, and left their 18-month-old son back in California with Frank’s mother.

Ruth worked as the colony’s secretary, librarian, and postmistress and was also its most avid chronicler, writing in The Nation about the “new Pennsylvania” they were building. She also wrote, even more revealingly, about her experiences in letters, a diary, and an unpublished memoir/novel. In these private sources Ruth describes the personal awakening she experienced in Siberia, where she fell in love with a Cornell-trained engineer she met in the colony office: a Jew, a Communist, and an avid reader of literature and philosophy. When Frank decided to go back to California amid a dispute between Wobblies and Communists, Ruth insisted that she wanted to fulfill her two-year contract, but actually, she had other reasons for staying: as she noted in her diary, “I want to be free, free!” She was not alone. Ruth noted in an article that she published in H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury, “In the spring of 1925 more than one matrimonial partnership melted, usually on the wife’s initiative. The colony women found in Siberia the freedom their souls craved.”

Kennell helped me begin to recognize the deeply personal attractions that American women felt to the Soviet Union, as well the moral and ethical compromises they made to rationalize so much that was deeply troubling about the Soviet system. Ruth was well aware of inefficiency, hostility to communism among many Russians, gender and ethnic conflicts, as well as the pettiness, corruption, cruelty, and ineptitude among Bolshevik leaders. But ultimately she still thought the Soviet experiment was worth supporting. Kennell’s friend Milly Bennett, author of the article on “American Girls in Red Russia” from which I took my book title, flippantly but also revealingly told a friend: “the thing you have to do about Russia is what you do about any other ‘faith.’ You set your heart to know they are right. . . . . And then, when you see things that shudder your bones, you close your eyes and say . . . ‘facts are not important.’”

Historians of the Russian empire have used Soviet citizen’s diaries to gain insights into “Stalinist subjectivity,” that is, the ways that individuals actively incorporated the Bolshevik ideal into their very sense of themselves. But diaries and other intimate sources have barely been tapped as a means of exploring ways in which the Soviet system likewise brought meaning to the lives of Americans and other foreigners. American women’s diaries and letters reveal both their genuine excitement—about Soviet schools, theatre, public spectacles, nurseries, workers’ housing, laws supporting maternal and child health, the “new morality,” and the simple fact of women’s visibility in public life.

“Women do everything here,” Louise Thompson wrote to her mother in the summer of 1932 from Moscow. “Work on building construction, on the streets, in factories of course, and everywhere.” Thompson’s activism on behalf of African-American civil rights had attracted her to the Soviet Union, and she wound up leading a group of 22 African Americans, among them luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes and Dorothy West to act in what was being billed as the first true-to-life film about American race relations. Although the film was never made, group members, several of whom stayed on in the Soviet Union, were treated like the stars they might have been, honored rather than shunned for their blackness. Thompson liked to joke, “It will really be difficult to scramble back to obscurity when we return to the old USA, I suspect.”

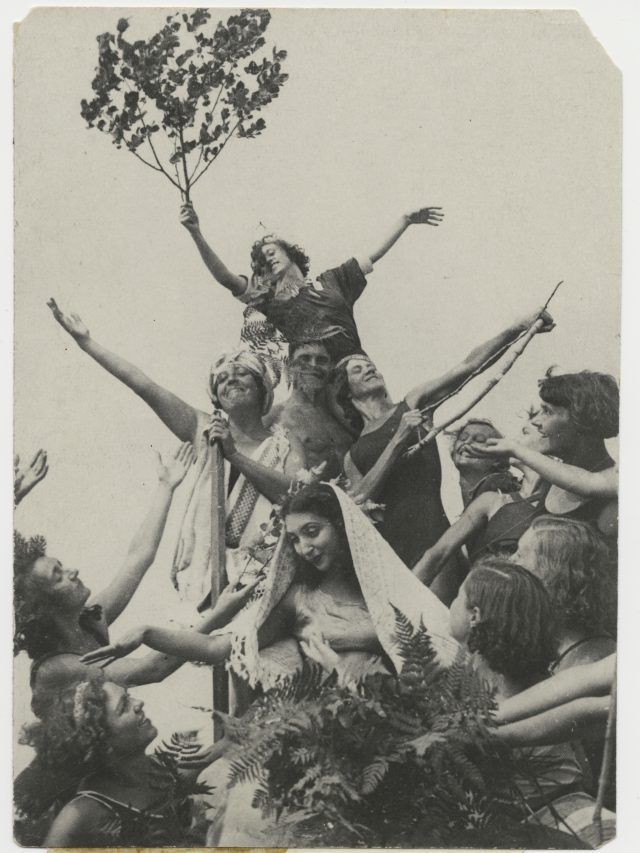

The young Jewish dancer Pauline Koner, like Isadora Duncan a generation earlier, was deeply inspired by the very fact of being in the Soviet Union and the opportunity that offered to embody a revolutionary ethos through her movement. “I have to pinch myself to really believe I’m here,” Koner wrote in her diary, in December 1934. “Since arriving on Soviet soil I’ve felt different, the air smelled different and the land looked different. . . . Moscow is the most energizing and invigorating place in the world. It is the place for creative thought and for happiness. Its beauty at times is unbelievable.” As a Jew, Koner had reveled in the experience of visiting Palestine; in the Soviet Union she reveled in the idea of shedding her ethnic particularity and joining the Soviet people.

My book includes suffragists, settlement house workers, “child savers,” journalists, photographers, educators, social reformers, and a range of “new women” who felt drawn to Russia and the Soviet Union from approximately 1905-1945.

Today, as American women continue to struggle for many of the same things as these women of yesteryear—satisfying work that will allow them to balance motherhood and career, romantic relationships that are not bound by economic incentives, and a way to make sense of a society that is exploitative, unjust, racist, and demeaning to women—Russia is once again in the news. Now, ironically, it is mostly right-wing men who see possibility in Russia thanks to its breed of capitalism that puts profit above all else. Like the Communist dictators of old, the new administration in Russia, utterly focused on its own power and gain, shows a callous disregard for individuals and personal freedoms. Meanwhile, American women—like women in many parts of the world—remain as hungry as ever for more just and satisfying social arrangements.

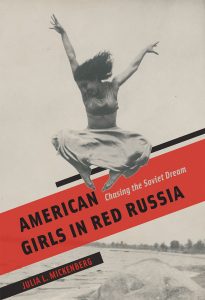

Julia L. Mickenberg, American Girls in Red Russia: Chasing the Soviet Dream (University of Chicago Press, 2017)

Learn more about Americans’ attraction to revolutionary Russia:

Warren Beatty’s classic 1981 film, Reds, captures the romance of the Russian Revolution for many Americans. Beatty plays the journalist John Reed and Diane Keaton plays his wife and fellow journalist Louise Bryant; dramatic reenactment of their relationship with each other and with the Russian revolution is interspersed with interviews from surviving members of their Greenwich Village milieu.

The Patriots, a novel by Sana Krasikov, tells the story of a woman who moves from Brooklyn to the Soviet Union, “in pursuit of economic revolution, a classless society, gender equality — and a strapping engineer she met while working at the Soviet Trade Mission,” as the New York Times’ review puts it. She stays in the Soviet Union much longer than most of the women I write about, at a high cost. The book chronicles not just her life in Russia but also that of her son, who returns to the Russia of his childhood and youth as a Big Oil executive, navigating Putin’s Russia as he tries to learn more about his mother’s past.

Mary Leder’s My Life in Stalinist Russia is the memoir of a woman who, at 16, went with her parents from Los Angeles to Birobidjian, a planned Jewish colony in Soviet Far East, but quickly decided this muddy, disorganized mess in the middle of nowhere was not for her and went on to Moscow. There she found she could not get a job without her passport, but when her father sent that on to her it was mysteriously lost in the mail. Leder felt she had no choice but to take Soviet citizenship—and hence wound up being stuck in the Soviet Union for more than thirty years.

Women, the State, and Revolution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life, 1917-1936 (1995) by Wendy Goldman speaks to both the ambitious Bolshevik program vis-à-vis women and children and the material and practical realities that prevented realization of the most utopian visions in realms ranging from social welfare to morality.

Anna Louise Strong’s memoir, I Change Worlds: The Remaking of An American, was a bestseller when it was published in 1935 and it offers an insightful picture into what motivated Strong to be a self-appointed propagandist for the Soviet Union, despite awareness of the system’s many limitations. She wrote the book hoping it would provide her with entry into the Communist Party, but in fact neither the Soviet or American parties would have her, despite having devoted much of her life to serving the Soviet Union.

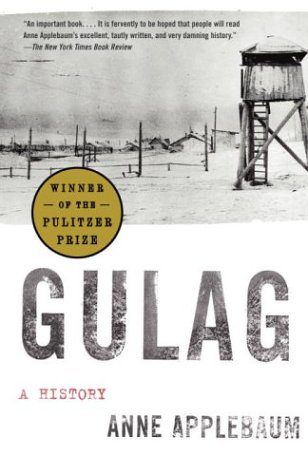

Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia. This popular history describes the thousands of Americans drawn to the Soviet Union during the First Five Year Plan, and the significant numbers who wound up in the gulag or dead, with far too little protest from the US Embassy.

that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.

that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.

by

by

This prison network – what

This prison network – what