Jonathan Brown teaches courses on the history of Latin American revolutions. He is now completing a manuscript on “How the Cuban Revolution Changed the World.” Professor Brown took the first of his four trips to Cuba in 2006. On the very day that the government announced President Fidel Castro’s incapacitating illness (August 1), Brown was touring the prison cum-museum where Fidel and Raúl Castro spent two years as political prisoners. Brown heard the news of the leadership change from the museum guide herself at the moment she was showing him the prison beds these two revolutionaries occupied in 1954. What a memorable moment for an historian!Since then, Professor Brown has busied himself negotiating the exchange agreement between the University of Texas and the Universidad de La Habana, organizing two UT conferences on Cuba, bringing three Cuban scholars to campus as visiting professors, reading thousands of documents on U.S.-Cuba relations, and delivering dozens of talks and papers on his research. Here are his thoughts on the implications for Texas-Cuba connections.

Within a week of President Barack Obama’s announcement about the renewal of diplomatic relations with Cuba, the Austin American Statesman ran a cartoon entitled “America Prepares to Invade Cuba.” It depicted a line of passengers dressed in beach wear boarding a plane heading to Havana.

Perhaps the cartoonist exaggerated, for President Obama merely loosened existing restrictions. Cuban Americans may travel to the island several times per year and send more money to relatives there. Non-Cuban Americans may travel there more freely, although special licenses are still required. The U.S. government will allow Americans to use their credit and debit cards in Cuba. The president may have cut the Gordian Knot ending 54 years of mutual hostility and eliminating one of the last vestiges of the Cold War. But he did not sever it completely.

Likely presidential candidate Jeb Bush has already stated that, if elected, he would reinstate travel restrictions. With two conservative Cuban Americans also likely to run for the presidency, including Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, the Cuban Embargo will remain a lively issue of debate. By the way, Jeb Bush holds a BA in Latin American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin.

The Cold War between Washington and Havana will not end until Congress says it’s over. That may not happen any time soon. Many Senators and Congressmen from Texas oppose the repeal of three pieces of “Cuban boycott” legislation dating from 1963, 1992, and 1996. Together these laws restrict travel, trade, and investment.

What changes may we expect in Texas-Cuba relations in the near term? More Texans will visit Cuba, not technically as tourists but in “cultural” exchanges. Students too. Literature professor César Salgado already is planning to take UT students on a Maymester trip to Cuba at the end of the spring semester.

President Obama’s announcement has ended restrictions on the use of U.S. credit and debit cards in Cuba—a positive boon that will enable Texans to compete for hotel rooms and rental cars on a par with travelers from Mexico and Canada. United and American Airlines are contemplating direct flights to Cuba from Houston and Dallas. For now, we Texans have to go through special charter flights from Miami International Airport. Of course, there are illegal alternatives that I do not recommend.

Will U.S. recognition encourage Cuban politics to become more democratic? Cuban leaders will say they have already established democracy. The Revolution assures equality for all and no citizen lacks for health care, education, and basic subsistance. Socialism, they say, has no room for the privileged and wealthy “one percent.” President Raúl Castro told the Cuban people that U.S. diplomatic recognition will not make the Communist Party give up power. He will hold power until 2018, when most of this year’s freshmen class will graduate from UT-Austin.

Where is Fidel Castro? He’s retired. Fidel never recovered fully from his 2006 operation for an intestinal blockage, and he has not appeared in public for many months. Raúl Castro is his brother.

Would Cuban political continuity be a good thing? Yes and no. Political stability will preserve the integrity of the Revolutionary Police and Armed Forces. Gang warfare, drug trafficking, and blatant corruption do not plague the Cubans as they do citizens of other Latin American countries. Even though many neighborhoods are blighted for the lack of building materials, Americans should feel safe wandering through Cuban cities. For example, personal safety in Havana compares favorably to Chicago, where the mayor’s son got mugged last month. Political continuity also has a downside. As in China, more engagement with the United States will not make the Cuban government any more tolerant of political protest. Dissidents will continue to face intimidation, prison terms, and deportation. At the very least, diplomatic engagement should remove Washington’s hostility as an excuse for suppressing domestic protesters.

Will Texas benefit economically from the loosening of restrictions? Very definitely, yes. Texans already sell agricultural products to Cuba through a “humanitarian” exclusionary clause in the embargo. American suppliers may send food and pharmaceuticals if the Cuban government pays for them before shipment. The arrangement is cumbersome.

For several years, the Texas-Cuba Trade Association, of which I am a volunteer consultant, has lobbied Washington to remove U.S. export limitations. President Obama accomplished as much as he could and Texas producers expect Cuban trade to expand. One Texas A & M economist predicts that our state’s exports to Cuba of chicken, pork, rice, beans, wheat, and corn could top $400 million within a couple of years.

Has the U.S. economic boycott really kept Cuba poor, as its leaders often claim? Only somewhat. Since 1990, when the Soviet subsidies ended, Cuba came to rely on trade and investment from every country of the world except the United States. Still, the Cubans are barely better off than when they lost Moscow’s largesse. Government over-regulation prevents entrepreneurial initiative. I traveled through the countryside last summer and observed little growing in the fields other than invasive spiny bushes called marabú. Cubans have to buy two-thirds of their foodstuffs from abroad.

Will Texas corporations receive repayment for the land and businesses confiscated by the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and 1960? No, they will not. Texas cattlemen as well as Standard Oil (today ExxonMobil of Irving, Texas) had grazing lands and oil refineries seized by revolutionary militias. Today, the Cuban government cannot afford repayment. Yet it will be strong enough to resist any such demands.

Will Cuban-Americans living in Texas be able to reclaim their lost properties? They might try but they will not succeed. Political continuity will reject such claims, and citizens now living in those houses and working those lands will resist as well.

How will loosening restrictions in U.S.-Cuban relations affect revolutionary programs promoting socialist equality? It already has. Since the end of generous Soviet subsidies in 1990, the Castro government promoted more tourism. Needing foreign exchange, Fidel also encouraged relatives abroad to send cash remittances to family members in depressed Cuba. Those Cuban citizens who had relatives abroad suddenly got more money to buy essentials than those who still depended principally on state rationing.

Cuba still maintains a dual monetary system. The state pays its employees in pesos. The hotels, shops, and restaurants operate on convertible dollarized pesos, called the CUC. One CUC equals about 20 pesos. Workers in the tourist industry get tips in CUCs and automatically make more money than state workers, teachers, public health workers, and even physicians. Therefore, income differentials are already disrupting socialist equality.

Will Cuban race relations change with an upsurge of tourism? Some experts say that more than half of Cuba’s eleven million people have some degree of African heritage. Remember that sugar and slaves went together in the Caribbean like cotton and slavery did in Texas. Because sugar grew all over Cuba and cotton only in the Deep South, African influences are much stronger in Cuban society and culture than in the United States. The 1959 Revolution further boosted Afro-Cuban prominence because many middle-class whites chose to flee to Miami.

Cuban race relations are refreshing and debilitating all at the same time. Today in the streets of Havana, visitors notice how easily persons of diverse racial backgrounds mingle. They work, play, socialize, marry, eat, and live together to a greater extent than in the United States. Fidel Castro boasted that the revolution ended discrimination in Cuba because it eliminated class distinctions. Yet racial prejudice did not end. White males continue to dominate the ruling party and military elites. Moreover, hotel employers apparently believe that European tourists prefer white hostesses and black maids, white waiters and black kitchen workers. More white Cubans live abroad and their remittances go predominately to white relatives in Cuba. The poorest and least healthy Cubans are mainly black.

Is President Obama correct that United States recognition will benefit the Cuban people? It will not change the government, and economically some will benefit more than others. However, I am convinced that U.S. diplomatic recognition of Cuba will benefit Texans as much as the Cuban people. Those UT students who want to learn about the Cold War in Latin America and about the largest Caribbean island will take advantage of the executive order. So will Texans who cherish the freedom to experience the only capital (Havana) of Latin America that does not have a traffic jam, the only cities of Latin America that still look like they did 50 years ago, and new places to snorkel that are not in Mexico. Believe it or not, Cuba has more live music than Austin.

Finally, what about those vintage Fords and Chevys? In the near term, they will remain the vehicles of choice in urban transportation. These 1940 and 1950 American models – DeSotos, Imperials, Buicks, Chryslers, Cadillacs, Nash Ramblers, and a Studebaker or two – share the roads with Soviet Ladas of the 1970s and modern Japanese automobiles. Detroit’s old cars have become part of the cultural identity of the country. But sooner or later, whenever commercial restrictions are lifted by Congress, Texas collectors may be able to repatriate many of these old-fashioned gems.

This author’s advice: Get yourself to Cuba before this aspect of the country’s charm disappears.

You may also like:

Jonathan Brown discusses Capitalism After Socialism in Cuba and President Lyndon Johnson’s phone call to Panamanian President Roberto F. Chiari

Blake Scott and Andres Lombana-Bermudez on the Panamanian tourism industry and Blake Scott on Cuban tourism

Photo credits:

First photo by Reggie Wallesen.

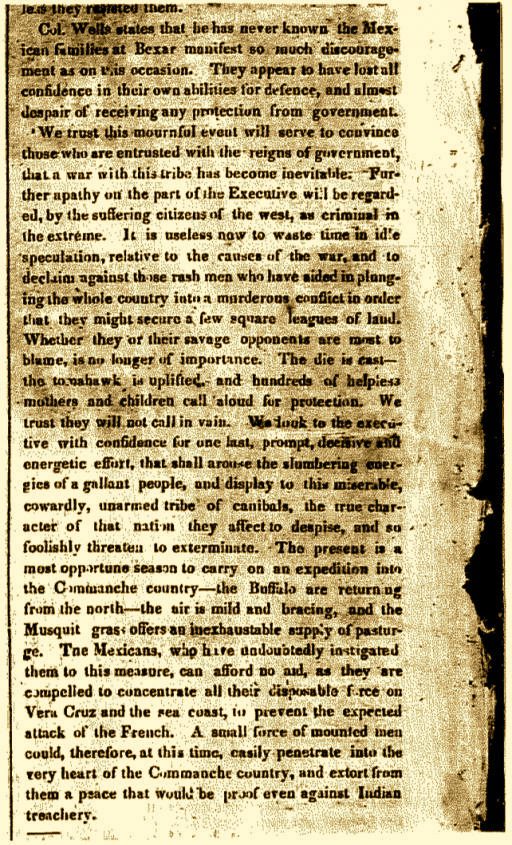

Remaining photos courtesy of Jonathan Brown.

Corrected to show that Jeb Bush earned a BA (not an MA as originally stated) in Latin American Studies at UT Austin (January 27, 2015).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.