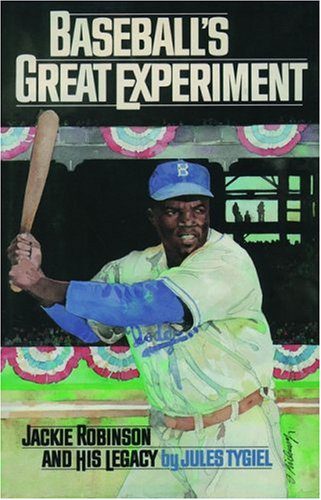

Historian Jules Tygiel presents not only an account of Jackie Robinson’s heroic struggle to integrate Major League Baseball, but a larger history of links between African American history, baseball, and the modern civil rights movement. Baseball’s Great Experiment further raises questions about race and sports in our current day.

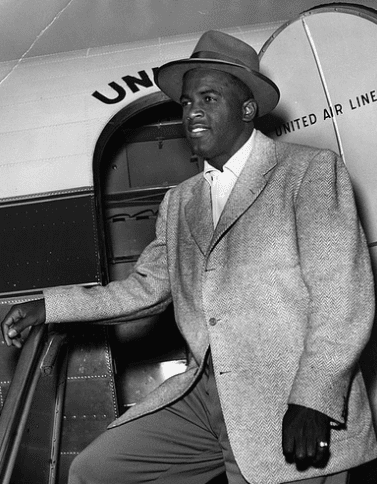

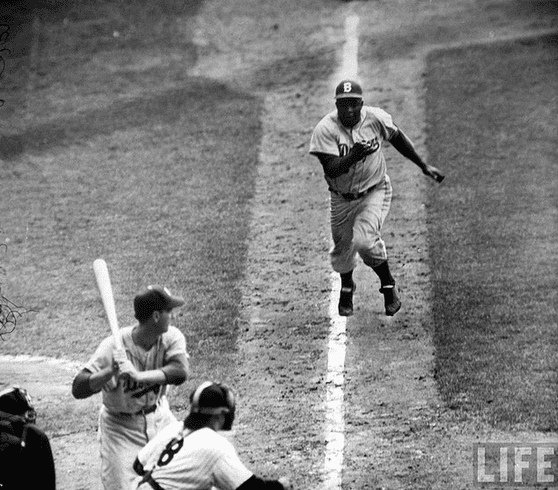

The integration of baseball in the immediate post-World War II years profoundly impacted American racial attitudes and culture. Baseball, the national pastime and most popular sport at the time, had remained segregated even as football and basketball had begun integrating. Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey became convinced that the integration of African Americans into Major League Baseball would serve as both a moral cause and an untapped resource of talented players that could strengthen his team. Rickey recruited Jackie Robinson, a former army lieutenant and exceptional athlete who had played numerous sports at UCLA, to initiate his great experiment. Robinson suffered threats, taunts, and abuse while breaking baseball’s color line in 1947, but performed remarkably on the field, carrying himself with a righteous dignity that amazed Americans. Tygiel contends that Robinson’s quest raised awareness among white Americans ignorant to the scourge of racism in their midst. Additionally, the integration of baseball influenced future civil rights initiatives by providing an example of brave nonviolent protest in the face of brutal opposition, and also through illustrating how economic factors could undermine segregation.

The integration of baseball in the immediate post-World War II years profoundly impacted American racial attitudes and culture. Baseball, the national pastime and most popular sport at the time, had remained segregated even as football and basketball had begun integrating. Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey became convinced that the integration of African Americans into Major League Baseball would serve as both a moral cause and an untapped resource of talented players that could strengthen his team. Rickey recruited Jackie Robinson, a former army lieutenant and exceptional athlete who had played numerous sports at UCLA, to initiate his great experiment. Robinson suffered threats, taunts, and abuse while breaking baseball’s color line in 1947, but performed remarkably on the field, carrying himself with a righteous dignity that amazed Americans. Tygiel contends that Robinson’s quest raised awareness among white Americans ignorant to the scourge of racism in their midst. Additionally, the integration of baseball influenced future civil rights initiatives by providing an example of brave nonviolent protest in the face of brutal opposition, and also through illustrating how economic factors could undermine segregation.

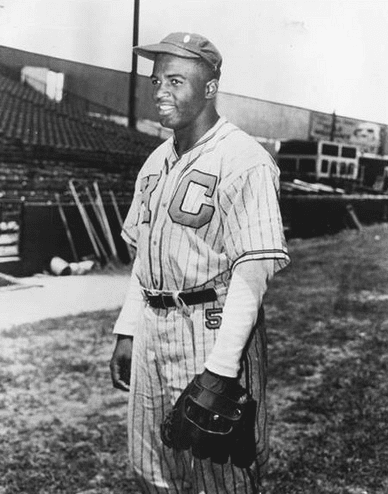

Tygiel emphasizes the importance of Rickey and Robinson’s endeavor in the struggle for black equality. Robinson played the 1946 season for the Montreal Royals before joining the Dodgers the next year, thereby also challenging Jim Crow in the minor leagues. Integration in the minors became as critical as in the majors, since farm clubs provided opportunities for blacks to develop their baseball skills. The author notes that black ball players in the minors often continued to face vicious racism, even after Robinson broke down the color barrier in the majors. Robinson’s success with the Dodgers eventually caused other ball clubs to recruit athletes from the Negro leagues, continuing baseball’s integration. Soon African American athletes like Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Satchel Paige starred in Major League Baseball. These ball players became heroes to the larger black community and caused whites to reexamine their racial attitudes. Black major and minor leaguers often challenged southern segregationist mores while in spring training by attempting to integrate hotels, restaurants, and other public venues, setting the stage for later civil rights battles. Tygiel argues that the successful coalition of black protestors (like Robinson), white liberals (such as Rickey), and sympathetic members of the press (both white and black) created a precedent for the modern civil rights movement.

Tygiel emphasizes the importance of Rickey and Robinson’s endeavor in the struggle for black equality. Robinson played the 1946 season for the Montreal Royals before joining the Dodgers the next year, thereby also challenging Jim Crow in the minor leagues. Integration in the minors became as critical as in the majors, since farm clubs provided opportunities for blacks to develop their baseball skills. The author notes that black ball players in the minors often continued to face vicious racism, even after Robinson broke down the color barrier in the majors. Robinson’s success with the Dodgers eventually caused other ball clubs to recruit athletes from the Negro leagues, continuing baseball’s integration. Soon African American athletes like Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Satchel Paige starred in Major League Baseball. These ball players became heroes to the larger black community and caused whites to reexamine their racial attitudes. Black major and minor leaguers often challenged southern segregationist mores while in spring training by attempting to integrate hotels, restaurants, and other public venues, setting the stage for later civil rights battles. Tygiel argues that the successful coalition of black protestors (like Robinson), white liberals (such as Rickey), and sympathetic members of the press (both white and black) created a precedent for the modern civil rights movement.

The economics of baseball in small town life also played a role in integrating baseball. Major and minor league spring training provided valuable income for hosting locales, most of which were in the South. After some initial resistance, southern boosters largely abandoned their protests against integrated teams for fear of losing their lucrative deals with baseball clubs. Economics outweighed social customs for most business people seeking to build a prosperous South.

The economics of baseball in small town life also played a role in integrating baseball. Major and minor league spring training provided valuable income for hosting locales, most of which were in the South. After some initial resistance, southern boosters largely abandoned their protests against integrated teams for fear of losing their lucrative deals with baseball clubs. Economics outweighed social customs for most business people seeking to build a prosperous South.

Yet while Robinson and Rickey’s great experiment achieved success, the author reminds us that inequality persists in baseball, and indeed, other sports. In the years following his retirement from baseball, Robinson became disillusioned with the pace of racial integration in baseball, and in society itself. The lack of African Americans in manager and front office positions in Major League ball clubs particularly disturbed him. Although the number of minority coaches has increased since 1983 when this book was published, we continue to see a disproportionately low number of minorities in coaching and organizational positions not only in baseball, but also in football, basketball, and in other sports, at both the college and professional levels of play. Baseball’s Great Experiment illustrates the fascinating story of the struggle to integrate baseball while encouraging us to contemplate the continued presence of racism in sports. Today, with sports occupying such a prominent place in American life, readers will benefit from studying this interesting and moving book about race and athletics.

Yet while Robinson and Rickey’s great experiment achieved success, the author reminds us that inequality persists in baseball, and indeed, other sports. In the years following his retirement from baseball, Robinson became disillusioned with the pace of racial integration in baseball, and in society itself. The lack of African Americans in manager and front office positions in Major League ball clubs particularly disturbed him. Although the number of minority coaches has increased since 1983 when this book was published, we continue to see a disproportionately low number of minorities in coaching and organizational positions not only in baseball, but also in football, basketball, and in other sports, at both the college and professional levels of play. Baseball’s Great Experiment illustrates the fascinating story of the struggle to integrate baseball while encouraging us to contemplate the continued presence of racism in sports. Today, with sports occupying such a prominent place in American life, readers will benefit from studying this interesting and moving book about race and athletics.

Photo Credits:

(Image courtesy of ozfan22/Flickr Creative Commons)

(Image courtesy of Black History Album/Flickr Creative Commons)

(Image courtesy of stechico/Flickr Creative Commons)

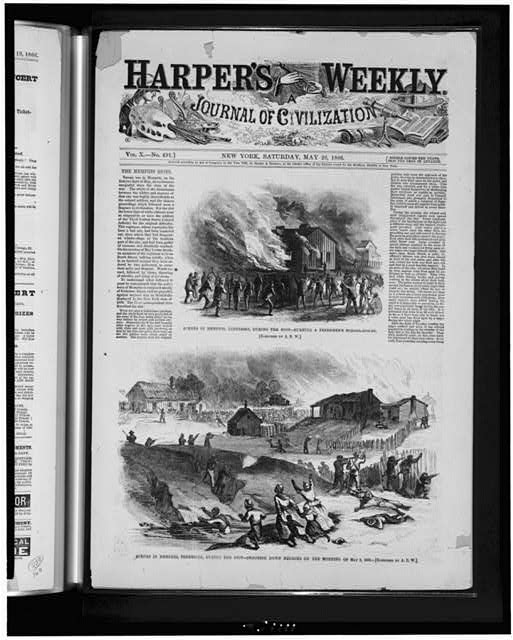

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

In the wake of the Russian launch of

In the wake of the Russian launch of

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with

The noise came from an unexpected Civil War re-enactment being filmed outside of his bedroom window. Horwitz had once been a little boy who would spend hours engrossed in an old, enormous book of Civil War sketches, captivated by images of Yankee and Dixie soldiers engaged in battle. But despite spending a number of years working as a war correspondent, it was this surprise encounter with the “men in grey” that prompted Horwitz to turn the critical gaze of the journalist upon his own and his country’s enduring fascination with the bloody conflict that pitted American against American in 1861-1865.

The noise came from an unexpected Civil War re-enactment being filmed outside of his bedroom window. Horwitz had once been a little boy who would spend hours engrossed in an old, enormous book of Civil War sketches, captivated by images of Yankee and Dixie soldiers engaged in battle. But despite spending a number of years working as a war correspondent, it was this surprise encounter with the “men in grey” that prompted Horwitz to turn the critical gaze of the journalist upon his own and his country’s enduring fascination with the bloody conflict that pitted American against American in 1861-1865. If the UN displayed the city’s position as a global capital of culture, politics, and economics, the deteriorating housing projects showed the city’s struggles with overcrowding, high crime rates, and poverty. According to historian

If the UN displayed the city’s position as a global capital of culture, politics, and economics, the deteriorating housing projects showed the city’s struggles with overcrowding, high crime rates, and poverty. According to historian  Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.”

Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.”  Like Smith,

Like Smith,