For many students, the most exciting thing about history is not the scholarly monographs that we spend years researching and writing and they are often expected to read. Rather, many students are most intensely drawn to the study of the past by reading and analyzing primary sources – the original documents that constitute the raw material of history.

Primary documents can sweep us into the past, giving us direct access to the words, cadences, biases, insights, and passions of remote historical actors. History comes alive, and voices whisper across chasms of time, space, and perception. In the best case, such material can enable students to make their own judgments about the past and to weigh the claims of scholars.

To promote the study of primary source material in my field, the history of U.S. foreign relations, I teamed up with two colleagues over the last few years to compile a volume of documents that we hope will inspire students to delve further into the subject.

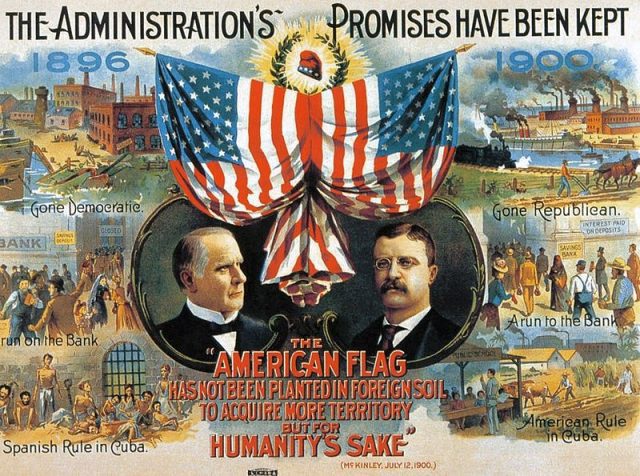

The book, America in the World: A History in Documents from the War with Spain to the War on Terror, encompasses about 125 years of history. It charts the rise of the United States from a peripheral, comparatively weak power in the late nineteenth century to the pinnacle of its military, diplomatic, and cultural influence in the early twenty-first. How and why did this momentous transformation occur? Who resisted and why? What were the attitudes of foreign nations as the United States became a great power of the first order and then surpassed them all?

Via 228 documents, the book helps answer these questions by inviting readers to consider the opinions and pronouncements of some of the people who took part in American policymaking and witnessed the American rise to power. Other historians have published collections of primary-source material on American foreign relations before. But our collection is new and different in at least three respects.

First, the book covers a relatively long period of time. Whereas most document collections focus on particular segments of this period, especially the Cold War, our book reveals and explores continuities across the larger flow of time, including the recent post-Cold War years. In fact, the collection features two chapters on the period since 1989, enabling readers to consider contemporary dilemmas faced by the Bush and Obama administrations in light of historical experience.

Second, the collection reflects key recent trends in the study of U.S. foreign relations. In recent decades, diplomatic historians have increasingly called into question the tendency among an older generation to write histories of U.S. policymaking on the basis of U.S. sources alone. Scholars should strive for a truly international kind of history that sets U.S. behavior within an international context and, by making use of foreign archives, views the United States through the eyes of foreign governments and peoples. Diplomatic historians in recent years have also called into question the field’s traditional focus on elite policymakers. Increasingly, scholars have recognized the need to take account of popular opinion and the influences of powerful people outside of government.

Our book takes account of both of these critiques of diplomatic history. To be sure, we include many documents reflecting the views of elite American policymakers – presidential declarations, policy memoranda, diplomatic dispatches, are still important sources. But we intermingle this kind of material, which has been the sole focus of nearly all the existing document readers in U.S. foreign relations, with two other kinds of documents: some reflecting foreign perceptions of the United States and others reflecting the opinions of Americans outside policymaking circles – clergymen, cartoonists, musicians, novelists, polemicists, and others.

Third, the book features relatively tight thematic coherence. There is, of course, an infinite number of documents that could reasonably have gone into our book. We handled the problem of over-abundance partly by building each chapter around a single interpretive question that guided our selections. Our chapters are not, that is, mere compilations of important documents related to a general topic or time period – the usual approach in document books. Rather, the chapters contain documents reflecting various perspectives on an interpretive problem that scholars have identified as crucial to understanding U.S. foreign relations. For example, the chapter on the great Cold War crisis of the early 1960s asks why the East-West conflict became so dangerous at that particular time. The chapter on the 1990s, asks how the United States reoriented its foreign policy following the collapse of the enemy that had given shape and purpose to American diplomacy for decades.

Following this approach, we place conflicting points of view in dialogue with one another to show the development of particular sets of ideas over time. While this approach means that we pass over some important questions, it does, we hope, enhance the book’s appeal by giving the chapters a clear logic and flow.

Whether we have achieved our goals is for readers to decide. But one thing that I and my co-editors – Jeffrey A. Engel of Southern Methodist University and Andrew Preston of Cambridge University – can say for sure is that the book was no small undertaking. Although all three of us pursued other projects at the same time, locating, selecting, editing, and writing introductory material for 223 documents took far longer than we had anticipated – nearly a decade, in fact.

But we’re pleased with the end result, and we hope that innumerable students – and perhaps other readers interested in America’s foreign relations – will use it in the years ahead to find inspiration for the study of history.

Jeffrey A. Engel, Mark A. Lawrence, and Andrew Preston, eds., America in the World: A History in Documents from the War with Spain to the War on Terror

Mark Lawrence’s suggestions for Further Reading can be found here.

You may also enjoy:

Introduction to America in the World

Mark Lawrence on Not Even Past: “The Lessons of History,” “The Prisoner of Events in Vietnam,” “CIA Study [on the consequences of war in Vietnam]”

Jonathan C. Brown, “A Rare Phone Call from one President to Another“

Campaign poster: Wikimedia

Duke Ellington Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Coca cola in Morocco via Creative Commons, ciukes/Flickr