By Lera Toropin

In flipping through old issues of Soviet Life, one finds a wide array of articles that present only the best that life in the USSR could offer: fashion, recipes, sports success stories, film reviews, detailed descriptions of beautiful travel destinations in Kislovodsk, Zheleznovodsk, and Naryan-Mar, all paired with colorful, enticing photographs. An almost too-good-to-be-true paradise, just beyond the Iron Curtain. “Wouldn’t it be nice to live like this?” the pages seem to ask, “Why don’t you come visit?”

Generally considered a “soft” form of propaganda, Soviet Life was a glossy magazine designed to present an informed, if not embellished look into Soviet culture for American audiences during the Cold War. At the same time, the U.S. published Amerika in Russian for Soviet readers. Everything worthy of showing off was often included in issues: Yuri Gagarin and the Soviet Space Program was an obvious choice; the achievements of Soviet medicine were another. Keep turning the pages and suddenly they’re whispering, “Don’t you wish you had universal healthcare like us?”

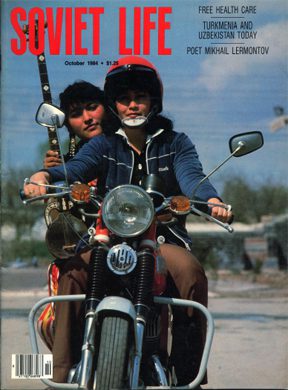

The October 1984 issue of Soviet Life (note the FREE HEALTH CARE at the top right) via glossycommunism

Certainly, the USSR had plenty to flaunt during the 1960s in regard to the health and well-being of its citizens. Services were cheap, life expectancy was up, and infant mortality rates were down, all thanks to the state-funded healthcare system called the Semashko model (after the first Soviet Minister of Health in the 1920s, Nikolai Semashko). However, the system was actually kept cost-effective and available to all because doctors were paid very low wages to maintain cost control for the public. Preventive medicine — averting the appearance of diseases through immunizations and healthy living — was the top priority. Prophylactics and visits to medicinal spas were stressed, yearly check-ups were made compulsory, and alcoholism was highly discouraged.

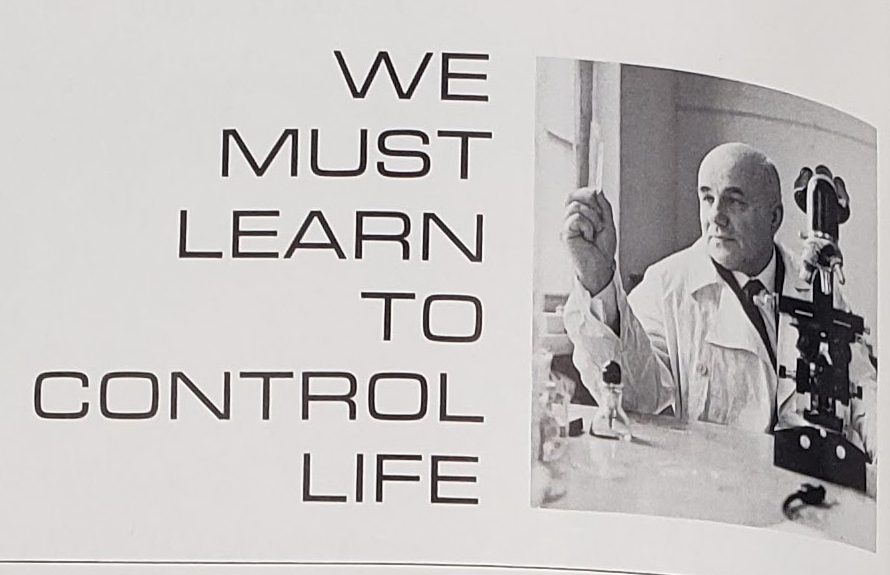

For a while, it worked. From its implementation in the 1920s, Russian citizens came to enjoy all the benefits their new healthcare system provided. The effects of the Semashko model peaked in the 1960s, and Soviet Life reflects that. Articles from 1966-1968 sing the praises of huge strides being made in medicine: a ground-breaking serum has been developed to treat and prevent infantile blood diseases, new radiation sickness treatments are being explored and optimistically predicted to be “controlled completely” in the near future, a brand new operation was just designed for the vertebral artery. Concrete achievements were documented to show American readers that Soviet healthcare was a success.

A new health resort begins construction in September 1986 via glossycommunism

If that wasn’t enough, the magazine was always ready to fall back on statistics to really underline that life wasn’t just good, it was improving. An engineer who designed a magnet to extract foreign objects from the body has trained 100 apprentices, many of whom are now experts; a pharmaceutical company in Kazakhstan is producing 33-35 million rubles’ worth of medicine annually – 30 different types, shipped to 26 different countries. In 1966, a reader from California writes in to ask, “Is it true that there is a shortage of medical doctors in the USSR?” “No,” the magazine responds, “not by our standards. We have 555,000 doctors. 23.9 for every 10,000 of the population.” To Soviet Life, the numbers speak for themselves.

So how did the magazine adapt when the reality turned sour? By the late 1970s and 80s, the Semashko model was drastically deteriorating and suffering from diminishing returns on its innovative investments. Years of focus on preventive care and “keeping healthy people healthy” caused rates of other illnesses to rise. Alcoholism did not decline, cardiovascular and heart diseases increased significantly, as did the mortality rate in adults. The number of doctors doubled to nearly 1.1 million, but with average salaries of approximately $210 a month and non-existent incentives, quality of care and training deteriorated due to apathy and low job satisfaction in the field.

Nikolai Dubin, winner of the 1966 Lenin Prize for his work on the chromosome theory of heredity and the theory of mutations via glossycommunism

Money also dried up. The system became so underfunded that citizens had to bring food to their sick relatives in the hospital because most state-fun facilities could no longer afford to feed their patients. Drugs were more difficult to come by, the system was not modernized, and suddenly, the care that one could get for free was being treated with skepticism and distrust.

In response to the growing healthcare crisis and lack of medical achievements to report on, Soviet Life simply carries on, omitting grim facts and doubling down on feel-good articles. Gone are the full-page spreads on the latest and greatest findings in Soviet medicine. Most articles in the 1980s now focus on descriptive writing and fluff pieces that seek to amplify the ethos of the 60s: a day in the life in a resuscitation ward, a travel guide-esque description of a health spa in the Baltic region. There’s a tone of desperation to it: “look here, don’t look over there.”

via glossycommunism

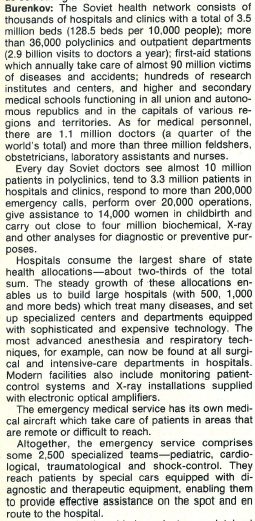

An excerpt of the interview with Sergei Burenkov via glossycommunism

One piece from 1984 stands out in particular. The word “free,” bold and in the center of the page, is repeated ten times. X-rays? Free. Lab Services? Free. The rest is an interview with the Minister of Health, Sergei Burenkov, and Soviet Life, once again, leans heavily on statistics and idea of low costs to emphasize the triumph of healthcare.

Burenkov piles numbers upon numbers like a shopping list until it’s difficult to grasp the weight of them. To a general reader, there’s no point of comparison. One is simply expected to bask in the fact that because there are 3.5 million beds in the USSR, the healthcare system is as successful as ever. One cannot immediately make the connection that the large number of beds did not prevent hospitals from overcrowding. Or that even with hospitals consuming two-thirds of the total share of state health allocations, they were still woefully underfunded. Reading the pages now, though, it is easy to look between the lines; amid everything Burenkov is detailing, there is plenty that he is choosing not to say as well.

The original Semashko model eventually collapsed with the USSR in 1991. But the echoes of its successes and failures remain, printed on the glossy pages of a propaganda-driven magazine.

Further Readings and Citations

- Garver, R. A. (1961). Polite Propaganda: “USSR” and “America Illustrated.” Journalism Quarterly, 38(4), 480–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769906103800405

- Rowland, Diane and Telyukov, Alexandre V. “Soviet Health Care From Two Perspectives” HEALTH AFFAIRS 1991 Fall; 10(3): 71-86

- “The Social Crisis in the Russian Federation.” OECD, 2001. 95-96

- Cooper R. “Rising death rates in the Soviet Union: the impact of coronary heart disease.” N Engl J Med. 1981 May 21;304(21):1259–1265

- Friedenberg, D S. “Soviet health care system.” The Western journal of medicine vol. 147,2 (1987): 214-7.

- Sheiman, Igor et al. “The evolving Semashko model of primary health care: the case of the Russian Federation.” Risk management and healthcare policy vol. 11 209-220. 2 Nov. 2018, doi:10.2147/RMHP.S168399

- Soviet Life, 1966 collection

- Soviet Life, 1968 collection

- Soviet Life, October 1984

You might also like:

Yugoslavia in the Third World: Not a New Bloc but Unity of Action in the Interest of Peace

Presenting Prague Spring to the West: Czechoslovak Life and Socialism with a Human Face

A Deportation Story: Russia 1914

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.