In 1867, less than three years after the assassination of U.S. president Abraham Lincoln, his (now widowed) wife and former first lady, Mary, traveled to New York in hopes of securing funds to cover her mounting expenses. Having acquired a significant amount of debt prior to her husband’s reelection and finding herself in an even more tenuous financial situation following his untimely death, Mary Todd Lincoln had resigned herself to selling off pieces from her famed wardrobe, which throughout her time in the White House had garnered much praise and attention. She was joined in this venture by the modiste who had designed much of the clothing Lincoln was looking to auction off, a formerly enslaved seamstress by the name of Elizabeth Keckley. The two had become acquainted after Keckley’s work for several notable D.C. society women (including the wife of Confederate president Jefferson Davis) brought her to Lincoln’s attention in the months leading up to the American Civil War.

Over the next several years, Mary and Elizabeth established a fruitful working relationship and a complex and intense personal one. Publicly, the dresses Keckley designed for Lincoln brought much-needed acclaim to the first lady and ensured a robust clientele for Keckley. Privately, however, the dynamics between the two women were much more uneven and often far less reciprocal. By her own account, Keckley was regularly called on to navigate Lincoln’s mercurial moods and bouts of despair, which frequently took Elizabeth away from her sewing business. In fact, after Lincoln’s 1867 plan to quietly sell off her clothing was discovered and quickly turned into a media spectacle, Mary retreated to her home in Chicago and left Keckley behind to contend with the fallout.

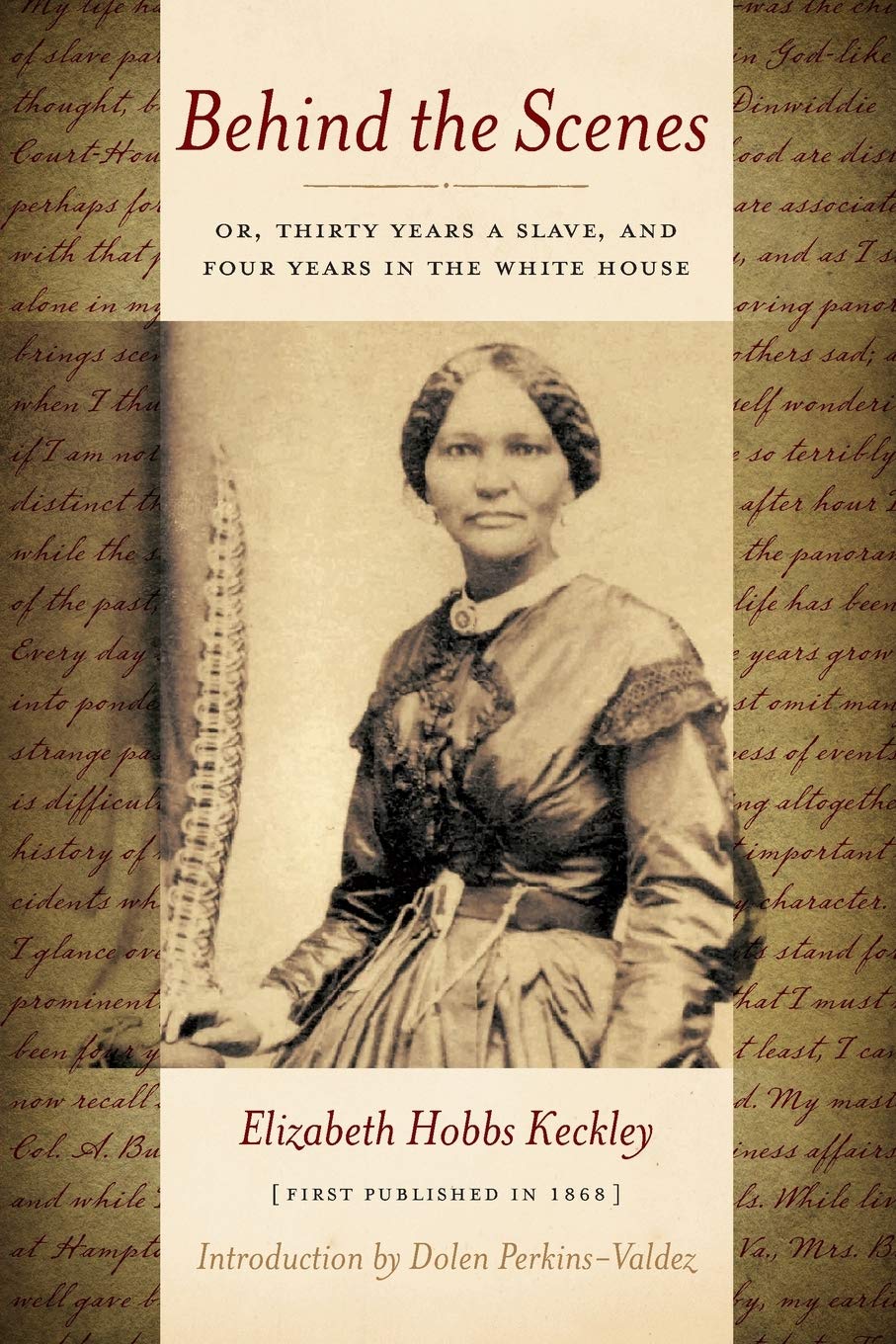

The following year, in an effort to salvage her former employer’s reputation (and likely her own), Keckley published a memoir detailing the events leading up to what had come to be known as the Old Clothes Scandal. It proved a compelling text entitled Behind the Scenes: Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. The book begins with a brief chronicling of Keckley’s years in captivity, beginning with her time in Virginia where she lived for much of her childhood, enslaved by the family of a Col. Armistead Burwell. Keckley spent her early years acting as nursemaid for Burwell’s young daughter before being sent to live with another of the colonel’s children during her formative years. Eventually, after multiple relocations, an ill-advised and ultimately short-lived marriage, and the birth of her first and only son, George, Keckley was able to purchase her freedom, after which she settled in Washington, D.C.

Behind the Scenes, however, moves very quickly from this account of Elizabeth’s youth and early adulthood to focus largely on her relationship with Mary Todd Lincoln—a fact that likely contributed to the immense backlash the text received upon publication. In the months following her memoir’s release, Keckley faced vast amounts of public censure stemming from several overlapping sources; firstly, the modiste’s (mostly generous but nonetheless critical) observations of the Lincolns’ private affairs perhaps inevitably triggered anxieties amongst postbellum elites about the possibility of their own domestic staffs engaging in similar forms of public exposure. Secondly, Keckley’s work came at a time when post-Civil War racial tensions were especially high, and ongoing questions about which narratives of slavery and freedom would be sanctioned might have colored readers’ perceptions of the text. This is especially true given that many readers may have unwillingly seen themselves reflected in Mary Todd Lincoln’s often exploitative and self-interested treatment of Keckley. The third and final potential factor in the pushback against Behind the Scenes, however, is perhaps the most telling.

Appended to the final pages of the text are multiple letters from Lincoln, written to Keckley during the height of the Old Clothes Scandal. Her messages are erratic and frantic, and this, along with reports that these letters were published without the consent of either Lincoln or Keckley, magnified concerns that the book constituted a violation of Mary’s privacy. However, it is also possible that reactions to the text in general and Lincoln’s letters in particular—including the former first lady’s purported anger at her long-time confidante and ultimate decision to permanently end their relationship—were not solely rooted in the belief that the missives were of too personal a nature to be made public. The intimate, at-times cloying, and potentially queer undertones of Lincoln and Keckley’s exchanges might also have played a part.

This subtle subtext underlies much of Keckley’s work, including the passages in which the seamstress comments on her former patron’s appearance, noting that Mary “had a beautiful neck and arm, and low dresses were becoming to her.” By her own admission, Elizabeth’s employment with Lincoln involved her spending “much of her time at the White House, often returning home only to sleep or give brief instructions to her employees”—a revelation that highlights the unusually extensive access Keckley had to her client. Given this, the question of what intimacies may have passed between the two women in the hours and days they spent alone in the first lady’s room (often with Mary in various states of undress) might have been a pressing one for readers attempting to parse Keckley’s later literary divulgences.

Much has been written about the Victorian-era notion of “romantic friendship,” within which nineteenth century women often formed amorous attachments to one another that sometimes lasted for years at a time and survived marriages, interstate moves, and intense scrutiny. Little of this scholarship, however, has considered the ways race likely shifted the dynamics and raised the stakes of such affiliations, with relationships like the one that developed between Elizabeth Keckley and Mary Todd Lincoln occupying a space of ambiguity. On the one hand, Lincoln’s words to Keckley indicate that the two shared a close connection, with Mary writing more than once about her desire to spend time with Elizabeth and emphasizing “how hard it [was not to] see and talk with” Keckley as the two struggled to recover from their failed New York venture.

On the other hand, given their wildly divergent social positions, it is unlikely that an intimate or “romantic” friendship between the two would have been viewed as permissible; indeed, it is possible that Lincoln’s concern over this very perception may have informed her outsized response to Keckley’s memoir and contributed to her son’s attempts to obstruct its distribution. After all, what were readers to make of Lincoln’s frequently suggestive notes to her former modiste, including her insistence that she eagerly awaited the day she could repay Keckley’s many kindnesses “in more than words?” Despite a public life marked by scandal, dismissal, and persistent rumors of madness, it would seem that even for Mary Todd Lincoln, the potential insinuation of interracial queer connection might have been a bridge too far.

After the publication and subsequent condemnation of Behind the Scenes, Elizabeth Keckley led a relatively quiet life, serving as an instructor at Wilberforce College and participating in multiple public service and fundraising efforts. Having lost, on a personal level, her access to Lincoln’s cache of social capital and, on a professional level, the patronage of the bulk of her former clientele, Keckley found herself living out her final days in relative poverty at Washington D.C.’s National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children. Though this reality is often romanticized in retellings of the famed seamstress dying with a portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln hanging over her bed, what it actually underscores are the disparities underlying the whole of Keckley and Lincoln’s relationship—disparities not even the promise of queer connection, and intimacies conducted behind the scenes, could surmount.

Notes:

Parts of this article are reprinted from Lyons, Candice. “Behind the Scenes: Elizabeth Keckley, Slave Narratives, and the Queer Complexities of Space.” Feminist studies 47, no. 1 (2021): 15–33

Candice Lyons is a Ph.D. candidate in The University of Texas at Austin’s Department of African and African Diaspora Studies and a 2021-2022 Black Studies Dissertation Scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her recent pieces “A (Queer) Rebel Wife in Texas” (2020) and “Rage and Resistance at Ashbel Smith’s Evergreen Plantation” (2020) can be found on Not Even Past. Lyons’ writing can also be found in the 2021 E3W Review of Books, for which she served as special section editor. Her 2021 Feminist Studies article “Behind the Scenes: Elizabeth Keckley, Slave Narratives, and the Queer Complexities of Space” is the winner of the 2020 FS Graduate Student Award.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.