Several years ago, while visiting Jamestown, Virginia, I had an epiphany; this isn’t American history, it’s English history—these people were English, and the America they strived within was a space more than an entity. Of course, this all changed with the American Revolution. So for obvious reasons, Yorktown, not far from Jamestown, didn’t give this Englishman the same sense of kinship. It may well have done so if I had read Andrew O’Shaughnessy’s excellent The Men Who Lost America before visiting.

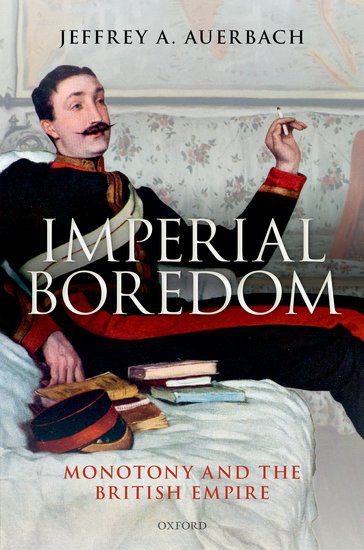

The cleverness in O’Shaughnessy’s work is found in the simplicity of its lens—reassessing the American Revolution through the lives of those who lost it rather than those who won. Two striking insights arise from this approach. First, the British did not lose America because of elite and illiberal buffoonery. Adopting a multi-biographical approach, O’Shaughnessy demonstrates that Lord North, John Burgoyne, Sir Henry Clinton—even Cornwallis and George III—were educated and capable men, cognizant of the latest and most sophisticated military strategies of their era. To suggest otherwise, as much historiography has done on both sides of the Atlantic for over 200 years, undercuts the spectacular achievements of the Revolutionary army.

Second, British logistics worked as effectively and efficiently as they could under the circumstances. However, “under the circumstances” is the operative phrase here – as much as O’Shaughnessy attempts to shy away from any form of determinism, he shows again and again that this was a war that Britain simply could not win. This is despite the fact that they prevailed in most of the major battles and occupied every American city of note, including New York, Boston, Savannah and Charleston.

Why was this so? Because, O’Shaughnessy argues, Britain chose to prosecute the war with “an army of conquest not of occupation,” meaning that the colonial rebels (remember, they weren’t Americans yet) could always flee, replenish their ranks, and regather their strength. Often, British success simply reinvigorated rebel recruitment drives. Meanwhile, the British use of billeting and foraging, as well as their recruitment of runaway slaves and indigenous warriors, did much to galvanize rebel resistance.

The appeal of O’Shaughnessy’s tome (nearly 500 pages in 9-point print) is its fresh perspective on a well picked over subject. Quite delightfully, he turns the American Revolution into English history, which it is – just like Jamestown. And for Americans, there is the new perspective of encountering George Washington as a factor rather than an agent. He shows up again and again in The Men Who Lost America — a problem needing to be solved, an elusive frustration, a precocious upstart, and (finally) the grave digger for British power on the continent. As such, Washington is cast in an altogether different light—he is someone being thought about rather than thinking, a mind to be reacted to rather than a mind reacting, a thorn rather than a rose.

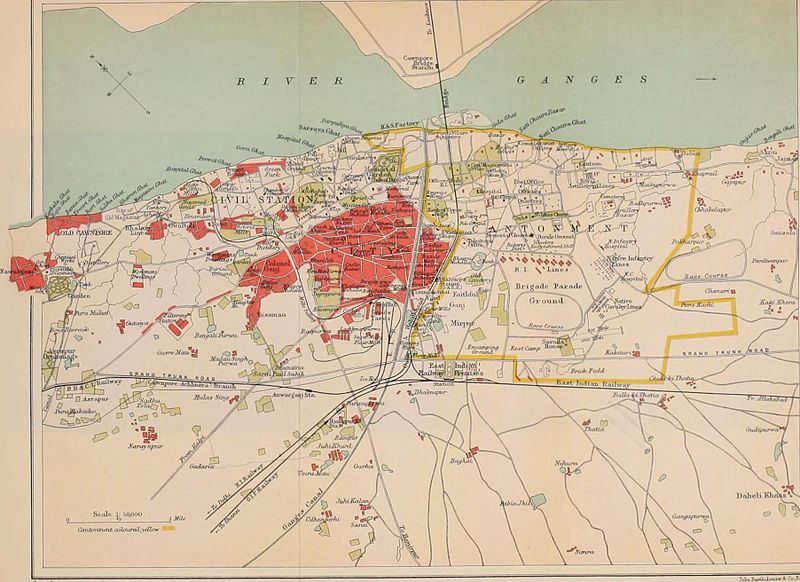

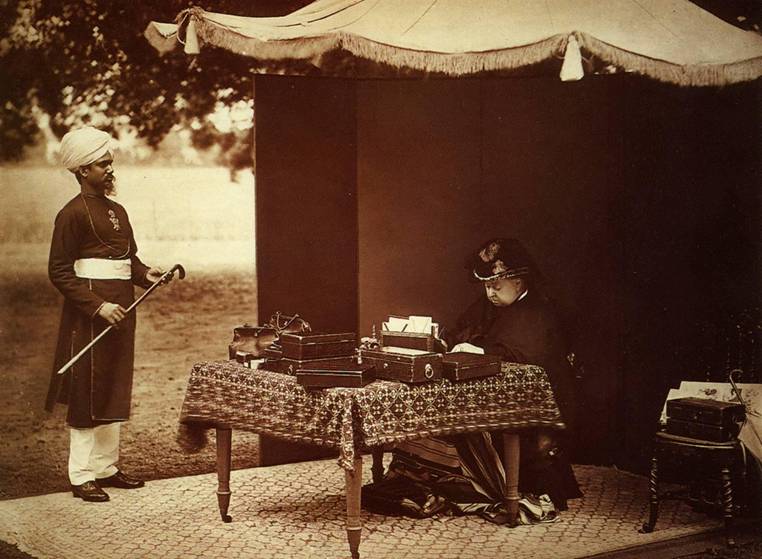

Despite the book’s originality and narrative luster, it ends on a strange, anti-climactic note, with allusions to the rather catch-all explanation of all British colonial mishaps—that London always cared more about other possessions than the one it was losing. In the last few paragraphs, O’Shaughnessy pivots to late 18th century British successes on the Indian subcontinent, though this would have been scant consolation to George III. Ireland was surely as important a factor as India for the British ruling class, as was keeping Canadian and Caribbean possessions. In this sense, many British war aims were in fact achieved. Furthermore, it is obviously inappropriate to think of Indian subjugation as some kind of imperial silver lining of the American Revolution. But Britain clearly did learn a great many lessons about soft power and modern war, while at the same time not exhausting itself before Napoleon and his eventual empire entered the picture.

This is ultimately what O’Shaughnessy misses, or at least does not emphasize strongly enough: the American Revolution was in some ways the beginning of British ascendancy on the world stage—and it was built on the thinking and action of men like North, Clinton and Rodney, most of whom saw their careers and reputations recover during the French Revolutionary Wars. What really gets going in 1776, or at least after 1787, is British ascendancy to the world stage. Furthermore, this ascendancy was built upon the rejection of military authoritarianism, which was so prevalent on the European continent during the second half of the eighteenth century. As O’Shaughnessy demonstrates again and again, British elites who prosecuted the war thought it was unwinnable—but they thought so precisely because they had no interest in constructing a continental style military regime of occupation and repression. There is much discussion of the sacrifices made by Americans on the altar of their emerging national identity during the Revolutionary War. Perhaps not enough is said about how many Englishmen did the same.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.