In Spring 2020, Professor Mark Ravina introduced a new variant on the highly successful, HIS 320W • Thinking Like A Historian. He describes the course as follows:

Historians use a range of analytical skills and our discipline, like the rest of the world, is entering the age of big data. In this class we will explore changes in American society using a massive data source, the hundreds of millions of names in the Social Security database. We will treat changes in baby names as evidence of broader political, social, and cultural change. When and why did the name Adolph drop in popularity? That should be obvious, but which name dropped in popularity the fastest: Adolph, Benito, or Hillary? Which name switched genders the fastest: Ashleigh, Kerry, or Jackie? Have personal names in the US become more or less diverse? Do the answers to these questions vary by state or region? Is Texas more “name diverse” than Wisconsin? Through these questions, we will explore the intersection of history with the interdisciplinary field of data science.

So that we can analyze name trends, this course will introduce the computer language R and review some basic algebra. Math and coding-related questions will include how to measure name diversity and how to calculate it by state and year. We will also explore more conventional historical sources and methods: newspapers, magazines, fiction and non-fiction books, and archival materials. Which politicians, celebrities, or fictional characters might have changed the popularity of a name? Was the name Marion, for example, already trending female when Marion Robert Morrison chose the screen name John Wayne? Did Cassius Clay spark a trend toward Islamic and Afro-centric names when he became Muhammed Ali? How do biographies, autobiographies, and other sources explain trends in names? How do those explanation match our quantitative evidence?

You do not need any special background in mathematics or computer science, just curiosity and a lack of “math anxiety.” If you have a strong math, stats, or coding background, you will learn to apply those skills to real world data. If not, this is a great introduction to data science. For all students, by combining humanistic critical thinking with computational analysis, this course will give you skills applicable to a range of careers.

This article highlights three innovative student projects that emerged out of this exciting new course.

William Kovach

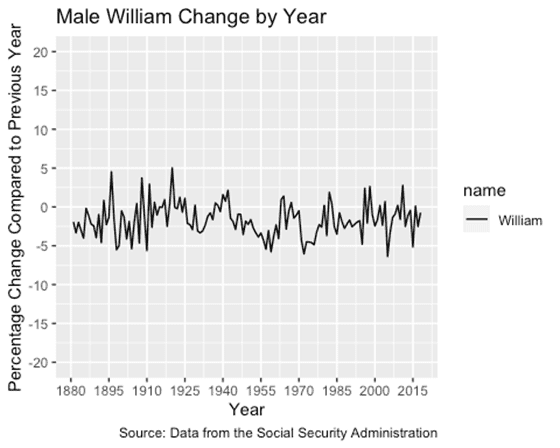

In the following excerpt, William Kovach discusses his first name’s popularity, and the various forces that impacted it. The project was focused on identifying how a name, in this case William, can serve as a lens through which to investigate US History more broadly.

The below graph shows the yearly change of the name William’s popularity, which has steadily decreased since 1880.

The name’s fall has been gradual and consistent, so similarly gradual forces—namely increasing name diversity, urbanization, and globalization—have likely contributed to it. Data demonstrate significant negative correlation between these phenomena and William’s popularity, and scholarly articles suggest that the forces may be causal.

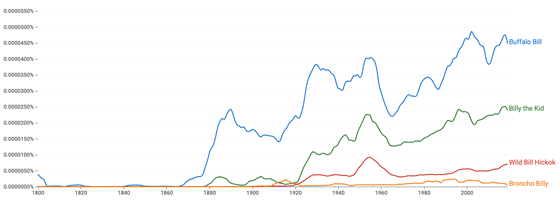

Nicknames of William have seen greater volatility than the name itself. This fact can be linked to characters and individuals known by the names in popular culture. Billy’s popularity, for example, rose considerably leading up to the 1930s. Bill was also popular during the period. Characters including Buffalo Bill, Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok, and Broncho Billy were popularized in association with depictions of the United States’ “Wild West,” and many of them were growing in popularity leading up to and during the early 1900s. This suggests that they may have influenced the nicknames’ popularity in the same period and the following one. The graph below shows the frequency of each of those character names in American English literature (from Google ngrams).

Liam Monahan

In the following excerpt, Liam Monahan discusses his given name and how it has grown in popularity following the rise to fame of certain actors.

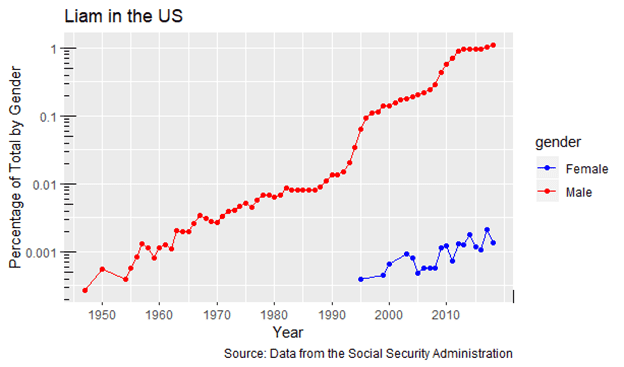

Baby names in the U.S. are deeply entrenched in popular culture. Liam, for example, was propelled on the wings of fame to become the U.S.’s most popular baby name in 2018. The name’s popularity soared from the depths of anonymity to the heights of conformist endorsements, all thanks to the 1993 movie Schindler’s List and its star, Liam Neeson. After the initial spike, the name surged while a successive chain of celebrity Liams supported its popularity. After achieving mainstream usage, Liam shed its Irish heritage and has expanded to become common in Hispanic, Black and Asian populations in New York state. Ultimately, Liam’s popularity proliferated throughout the US, including Puerto Rico, and spread abroad to Canada, France, the UK, Spain and Switzerland.

Liam’s rise in popularity is connected chiefly to the Academy Award winning film, Schindler’s List. In fact, Liam and Oskar (with a Germanic “k”) both soared after the film. According to The New York Times, Liam Neeson played the protagonist Oskar Schindler with “mesmerizing authority” and “unmistakably larger than life, with the panache of an old-time movie star” (“Review/Film: Schindler’s List; Imagining the Holocaust to Remember It – The New York Times.” Accessed March 28, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/15/movies/review-film-schindler-s-list-imagining-the-holocaust-to-remember-it.html). This relatively obscure name – uniquely spelled with a Germanic “k” and not Anglicized “c” – surged in popularity in 1993, corresponding with the release of Schindler’s List and in parallel with the spike in the name Liam. Oskar rose from near anonymity to 0.0013% in 1993 and finally 0.0073% in 2018, a 462% increase. Oskar increased amongst boy baby names from 1993 until 2009, jumping 444%. Notably there was no similar rise in the related and more common name Oscar, spelled with a “c,” which subsequently diminished in popularity.

Patrick Smith

Patrick Smith examines his first name and its connection with religion and demographics.

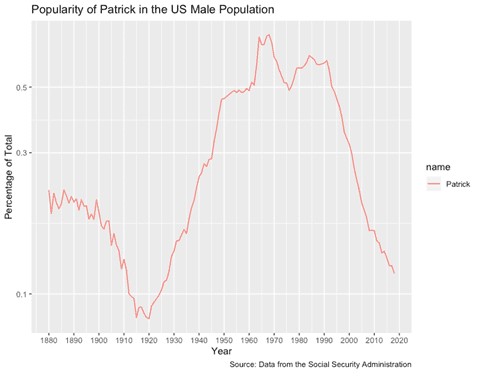

“Patrick” has historically been a popular male name in the United States. Its popularity peaked in 1968, when it was given to 0.751% of male babies born (Social Security Administration 2020). The name has steadily declined in popularity since and was given to only 0.117% of male infants born in 2018, (Social Security Administration 2020). (See Figure 1).

The name’s association with the 5th century patron-saint of Ireland, Saint Patrick, may explain why the decline of its popularity has coincided with declining religiosity and shifting demographics in the United States. In 1976, 81% of Americans identified as white Christians, but by 2017 only 43% did so (Cox and Jones 2017). Weekly church attendance amongst Catholics decreased from 75% to 39% between 1955 and 2017 (Saad 2018). Amongst 20-29-year-old Catholics, church attendance has declined from 73% to 25% (Saad 2018). This may contribute to the declining selection of “Patrick”; decreasing religiosity likely lessens desire to name children after saints.

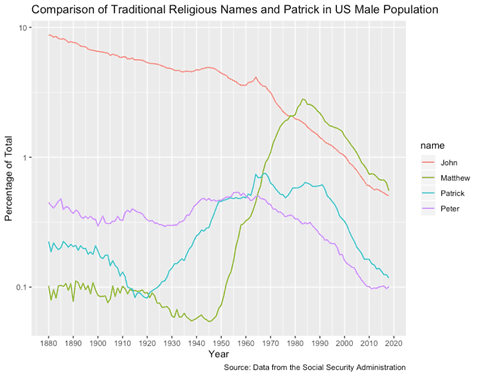

This trend seems also to have affected other religious names, such as those of the Apostles. (See Figure 2).

Certain religious names will likely continue to decline as American Christians become less numerous and less devout.

References

Cox, Daniel and Robert P. Jones. “America’s Changing Religious Identity”. Research. PRRI, September 6, 2017. https://www.prri.org/research/american-religious-landscape-christian-religiously-unaffiliated/.

Saad, Lydia. “Catholics’ Church Attendance Continues Downward Slide.” Politics. Gallup, April 9, 2018. https://news.gallup.com/poll/232226/church-attendance-among-catholics-resumes-downward-slide.aspx

Social Security Administratio