At the height of the Spanish Empire, the Manilla Galleon – an annual flotilla between Manilla and Acapulco – was considered the lifeline of Spain’s economy, bringing silver from the mines of New Spain to the markets of Asia. On the reverse trip, the galleons would be loaded with Asian luxury goods, such as spices, silks — and slaves. This episode presents a micro history of the Trans-Pacific slave trade through the lens of Diego de la Cruz, a chino slave who managed to escape and evade capture for three years in the highlands of Central America. Guest Kristie Flannery found Diego’s story in the Spanish colonial archives, and narrates his tale in the broader context of the powerful political and economic forces at work in Spain’s global empire.

Public and Digital: Doing History Now

Three years ago I broke a promise to you.

In the spring of 2013, I wrote two articles on the digital technologies that were changing the way we do history: one on blogging (Digital History: A Primer Part 1) and one on digitizing documents and images (Digital History: A Primer Part 2). I promised to write a third article on what I called “Digital History For Real.” I never wrote that third one.

At the time I was scouring the internet for digital history projects that were using computer technology to produce new kinds of historical documents that I hoped would generate new historical questions or new historical methods, and eventually yield new ways of thinking historically and new insights into the past. To share what we were finding, we started The New Archive, a series of reviews of digital history projects. The first two entries covered an online archive about the Irish Easter Rebellion of 1916 and an interactive map called Visualizing Emancipation about the surprisingly long-term and often violent process of resisting and ending slavery in the U.S. Along the way, we found marvelous maps, archives of sounds, even a database of feelings. We found data visualizations of stunning creativity and graphic appeal. Our most recent front-page feature, by UT art historian John Clarke, displayed the ways gaming technology can be used to reconstruct ancient buildings and make them accessible to everyone. And about a year ago, in November 2014, we offered a list of resources on digital history, in case you wanted to start exploring on your own.

These projects were each presented in increasingly sophisticated and eye-appealing ways, which is important, but, for the most part, they were using digital technology to do the same kinds of history we have always done. I never wrote that third article because a new digital history hadn’t yet materialized.

Now I think that we are on the cusp of seeing some very impressive new uses of computational thinking and digital presentation of databases, mapping, and text mining – all of which have had more impact in digital humanities fields other than history until now. And I promise (!) that I will write something about those developments later this month.

First though, today I want to talk about the ways that historians have been using digital methods to make history more appealing and accessible to the public. This is the realm where Digital History and Public History overlap. So far, public history has benefited from the digital more than any other kind of work historians do.

I’m defining public history as any activity that makes high quality, professional historical research and writing available and accessible to the public. This differentiates it from popular history, which, at times, can be as good as public history but also includes all kinds of dubious junk.

Not Even Past is public history, like other kinds of online history writing and blogging. Public history, which appeared well before its digital enhancements, also includes the work of museums and archives, the preservation and display of historical sites, the collection of oral histories, and the production of documentary photography and filmmaking. Public historians work for private and public institutions, government and business. In 1979, the National Council on Public History was formed; its website is a great resource for information about doing and enjoying public history. And in 2013, The Digital Public Library of America was launched online as a national digital library.

The internet, computational technology, and digital film and photography have made much more professional history available to the public than ever before. Much of that newly available history is visually exciting and effectively interactive and it is changing the ways public and academic historians go about their work. In many cases Digital History and Public History overlap. The most obvious case is the vast number of online archives: digitized documents, books and other texts, films, photographs, and other images that are available to the public, while at the same time providing fundamental research materials for academic historians.

Another area of overlap is in the practices of openness and collaboration. Digital projects often require the work of people with diverse skills in programming, archiving, and data analysis, but collaboration goes beyond the specialists who produce projects. As Ben Schmidt put it, “collaboration in the digital humanities manifests itself not just among those involved in creating digital scholarship but also with the audience. Through comments and feedback sections, social networks, and other mediums, historians are able to engage with their audience on an unprecedented level.” This kind of openness to multiple voices is beginning to have an impact on academic history, but it has already been shaping many public history projects. For example, Vicki Mayer and Mike Griffiths describe their project MediaNOLA as a website for showing “the invisible contributions of ordinary people, places, and practices in the creation of New Orleans culture and its representations.” They quickly realized that in order to show the role of ordinary people in creating a city’s culture, they would need to engage those people in producing the website and that included training students to work with local librarians, archivists, and institutions.

Public interest in history is also served by collaborative, self-generated digital platforms. Television and movies, with all their romantic and entertainment oriented distortions, remain incredibly popular, but they are joined by outlets that satisfy the public’s desire to know “what really happened.” This is a question that can now often be answered easily and relatively authoritatively online. AskHistorians, for example, one of the many specialized and moderated pages of Reddit, the huge (sometimes scandalous and often misogynous) information sharing website, “aims to provide serious, academic-level answers to questions about history.” With 450,000 registered readers, AskHistorians is a lively open forum for discussing history. Crowdsourcing has its well-known problems, but it is worth noting that studies comparing Wikipedia and the venerable Encyclopedia Britannica carried out by Nature in 2005 and Oxford University in 2011 found them to be equivalently reliable.

Not only is there more historical information more widely available, but the technology has made all kinds of information available in exciting new visual forms that are relatively easy to produce. Data visualization is so popular now that there are dozens of free software programs that are openly available and easy to navigate and many other sites like Rice historian Caleb McDaniel’s, to instruct anyone on using them. We have already reported on excellent data visualization projects from big digital history labs like those at Stanford and Harvard as well as individual projects hosted at other universities and institutions elsewhere.

These visualizations raise important and unanswered questions about the differences between seeing and reading. To take just one example, a 14-minute video made in 2012 by Japanese artist Isao Hashimoto, illustrates each detonation of a nuclear weapon between 1945 and 1998, with a flash and a sound. One historian claimed that “almost anyone watching the animation will come away with a deep understanding of the key features of the nuclear age.” Now, while the video powerfully conveys the high number of explosions, it is impossible to derive a “deep understanding” of anything from watching it, because it violates almost every fundamental rule of historical presentation: it offers no way to think about or contextualize the data, and no way to verify its accuracy. Other commentators come closer to the mark in pointing out its emotional impact. For example, on Open Culture, Kate Rix called it “beautiful” and “eerie,” and said its laconic style makes it “work better” than excessive films like Oliver Stone’s historical psychodramas. Hashimoto’s video “works” as an art object because it generates feelings, conveys some generalized knowledge, and might stimulate the viewer to learn more. But it fails, in my opinion, to become anything more complex than a simple timeline, however beautifully rendered, because it lacks all analytical credibility and depth.

I’m not arguing against such visualization of historical data, just the opposite. We know that the visual has a visceral impact on us, an effect that often skirts around words and goes straight through our senses to our feelings. A famous (or internet-famous) marketing info-graphic claims (correctly) that we process visual information much more quickly than text. But what are we processing? What kind of history are we “learning”; can visuals that exclude the precision of words manipulate our feelings more stealthily?

I’m asking how we can harness that visceral and emotional power used by public and popular historians to academic data analysis. I’m also asking how we academic historians can do a better job writing for the public. One place to start is by asking how museums, historical sites, and films, for example, use that emotional power and our ability to identify with what we see to convey historical information and encourage thoughtful responses in their public audiences? How can we, as academic historians, work with professional public historians to learn what works in a documentary film or museum exhibit or Reddit, to understand how better to convey our own work to public audiences? And how can we apply this galaxy of ideas to our research and teaching?

This year at Not Even Past, we plan to dig much deeper into the ways that digitization and public accessibility are changing historical research, teaching history, disseminating history online, and training graduate students to become historians. I know I speak for many of my colleagues and readers, when I say that we are learning as much from our students about digital tools as we are teaching them.

We will also introduce a new page, Thinking in Public, devoted to public scholarship in all fields. One of the problems we face in entering these new fields is the lack of adequate archiving and indexing projects in digital and public history. Thinking in Public will seek to create a database of public scholarship projects conducted at UT Austin as well as to review and promote them. We will also be seeking to review the most interesting public scholarship taking place at other universities.

We have a new staff member to coordinate our Public and Digital History initiatives. He is Edward Shore, a UT History graduate student specializing in Brazilian history. You’ll recognize him as the author of some of our favorite NEP articles on Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto’s famous album and Hugo Chavez. Eddie will work with our current Senior Assistant Editor, Mark Sheaves, to commission and contribute to a series of articles about becoming historians in the digital age, and about their own forays into public history.

We will continue to offer the best historical writing in our reviews and articles, but we will also be thinking about how we can use new digital and public history practices to make us all better and more interesting historians who can speak to larger and more diverse audiences.

Featured image adapted from Steven Lubar, “Teaching Digital Public History,” January 2, 2014.

New Digital Technologies Bring Ancient Roman Villas to Life

If Poppaea, the purported owner of the grand Roman villa that has come to light near Pompeii, were to walk into her slaves’ quarters today, she would think the gods had enchanted it. What are these banks of red flashing lights and strangely-dressed men and women manipulating words and pictures on magical tablets? It’s the Oplontis Project team, using digital technology to reanimate her Villa, which was buried in ash on August 24, AD 79, when the Mount Vesuvius volcano erupted near Pompeii.

Oplontis Villa A, north façade and garden after replanting in 2010. Photo by John Clarke. ©The Oplontis Project

Italian excavations between 1964 and 1984 uncovered 99 of the villa’s spaces, including over forty exquisitely-decorated rooms, four large gardens, and a 61-meter swimming pool. After a hiatus of more than 20 years and on the invitation of the Italian Ministry of Culture, I assembled a team of experts to excavate, study, and publish Poppaea’s Villa (officially known as Villa A at Oplontis, Torre Annunziata, Italy), a UNESCO World Heritage site. The high-speed internet and multiple computers that would astonish Poppaea are only a small part of the arsenal of digital technologies that are bringing her villa to life.

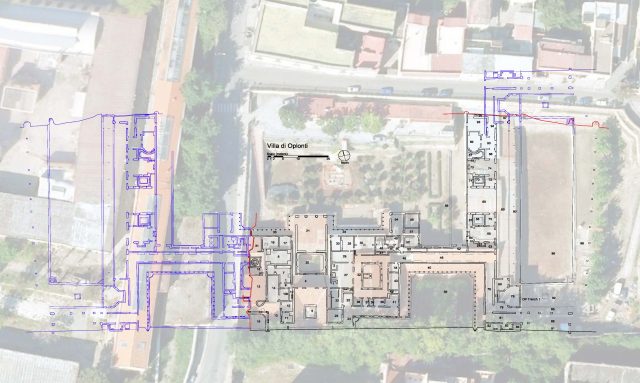

Aerial view of site with superimposed plan of actual and hypothetical remains. Drawing Timothy Liddell. ©The Oplontis Project

Given the many unanswered questions about what had been excavated, the Oplontis Project chose not to attempt to bring to light the estimated forty rooms that still remain under a nearby military complex, but rather to study fully what was there. This meant conducting the first excavations beneath the AD 79 level to learn about earlier phases of the villa and to carry out geological surveys to understand its relation to the surrounding land- and sea-scape. It also meant dealing with thousands of orphaned fragments, combing archives to track the procedures used to recreate the villa, and analyzing the chemistry of everything from ancient carbonized wood, to the pigments used in the frescoes, to the marble used throughout the Villa.

To address these challenges in the most efficient way, we adopted three digital strategies: the born-digital e-book for publication; a flexible database to collect and share resources; and a navigable 3D model to record the actual and reconstructed states of the Villa.

In light of the limitations of print publication, we chose the most successful scholarly publisher of digital e-books, the American Council of Learned Societies Humanities E-book series. Their ambitious e-books typically have excellent finding tools and hyperlinks to a myriad of electronic media, including archive repositories, databases, and films. Our book, Oplontis: Villa A (“Of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy is now available for free on-line.

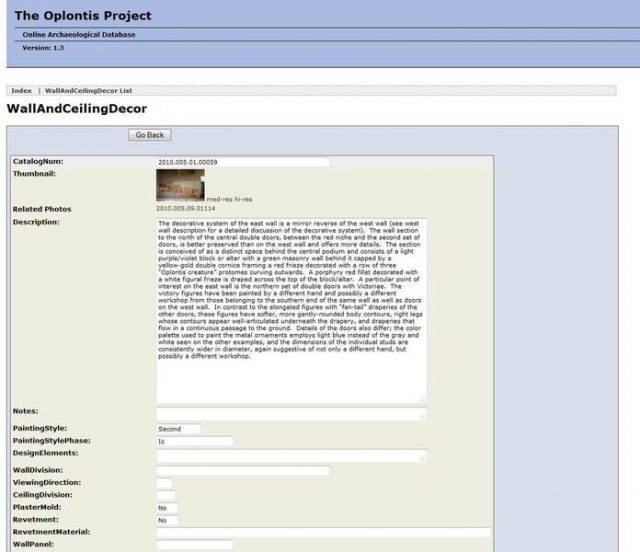

The Oplontis Project database developed parallel to the ACLS e-book; indeed some of the contributors to the e-book began work on their chapters by building their part of the database. For this reason it includes all of the categories of research we are doing, including the decoration of all surfaces, the architecture, excavations, archival materials, and photographs. In this sample page from category 1, Wall and Ceiling Decorations, we see the east wall of the atrium, the top part of the catalogue description, written by Regina Gee, and a thumbnail image of the wall.

Clicking on the thumbnail we get a screen showing the actual-state photograph taken by project photographer Paul Bardagjy in 2009. From here we can link to scores of archival photographs of this wall, including details of the wall when it was in better shape.

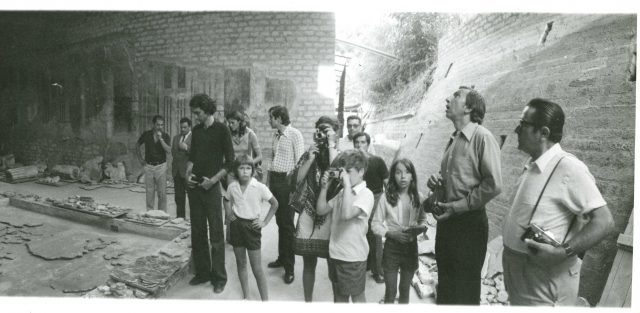

One of the archival photos linked to this wall recently came into our hands from a private collector in the town of Torre Annunziata. It shows what the atrium looked like when Princess Margaret of England visited the Villa in 1973—years before it was open to the public.

Oplontis, atrium 5. Visit of Princess Margaret and entourage 14 August 1973. Courtesy the Vincenzo Marasco Archive. ©The Oplontis Project

Notice that the Princess is shooting photos—and also notice the leftover fragments lying on the floor. A yet earlier photograph, from the Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, shows what the wall behind the royal group looked like at the time of excavation, around 1968: it was in a state of collapse. The wall paintings a tourist sees today were literally salvaged from the debris, consolidated with reinforced concrete backings, and re-hung on a wall made from modern materials.

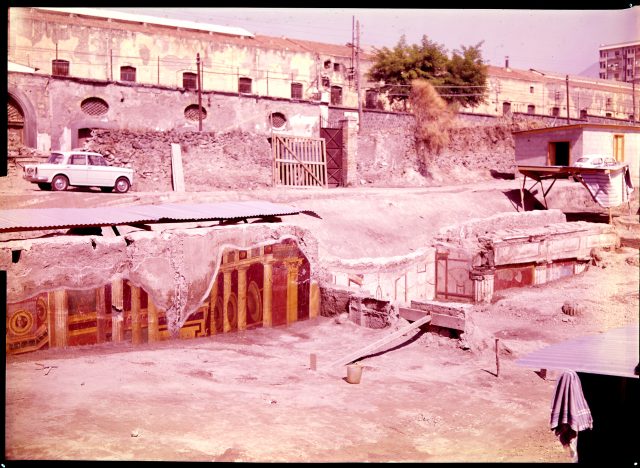

Oplontis, atrium 5, east wall. Photo the Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, 1968_45_24. © The University of Maryland

As this historical photo shows, when excavations began on the west wall of the atrium in 1966, it was miraculously standing to the level of the architrave (Fig. 7).

Oplontis, atrium 5, west wall, at beginning of excavations. Photo courtesy the Soprintendenza Archaeologica di Pompei, De Francisis Archive, dia 9.392

After reconstruction, it was clear that the top part of this wall had succumbed to the blast of the pyoclastic flow, displacing fragments of its upper zone. When we located the fragments piled on the floors of several storage areas (transformed today into our laboratories), we had the basis for reconstructing an Ionic second story, which you can see below.

Oplontis, atrium 5, west wall. Reconstruction by Martin Blazeby, King’s Vizualisation Lab. © King’s College London

As one sees it today, the modern roof is some three meters too low. The 3D model allows us to reconstruct the interior of this and all the other spaces of the Villa, finding homes for the many fragments of painted and stucco decoration (over 3,000 in all) that were left over when funds ran out.

Not only have we been able to put fresco fragments into their context through digital means, we have also reconstructed whole rooms. A case in point is the transformation of a seemingly featureless space into the most lavishly decorated reception room in the Villa.

The process of reconstructing room 78 started with my discovery of a cryptic note in the excavation daybooks for 1974 mentioning that excavators had found a series of impressions of wood panels in the hardened volcanic ash. This is a kind of wall revetment never before attested in antiquity. What of the floors and wainscoting, stripped of their marble in antiquity? Simon Barker closely studied tiny fragments of marble residue, identifying the range of expensive marbles used in that one space and reconstructing the patterns on the floor and walls. Architect Timothy Liddell put all of this data into a 3D environment to provide a stunning—and unprecedented—visualization of this opulent room, a unique testimony to the tastes of super-wealthy patrons like Poppaea.

Oplontis, diaeta 78. Digital reconstruction. Timothy Liddell and Simon Barker. ©The Oplontis Project

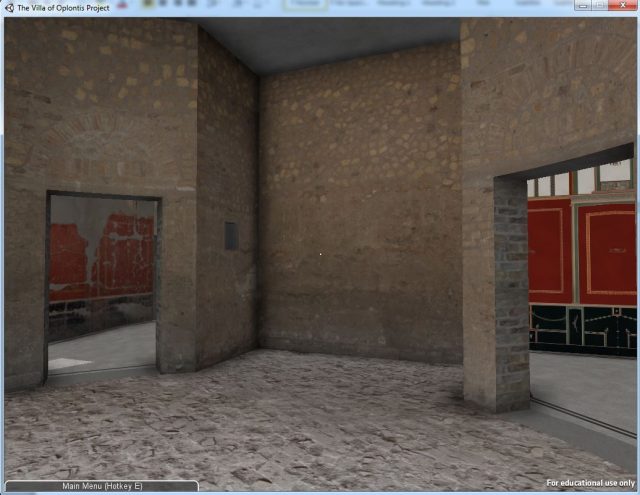

All of these room reconstructions are in the process of being integrated into a 3D model of the whole site. In its current beta version, the 3D model gives a user unlimited access to the entire 100 x 200 meter site, the same access available to the Oplontis Project team under the terms of its collaboration with the Archaeological Superintendency of Pompeii.

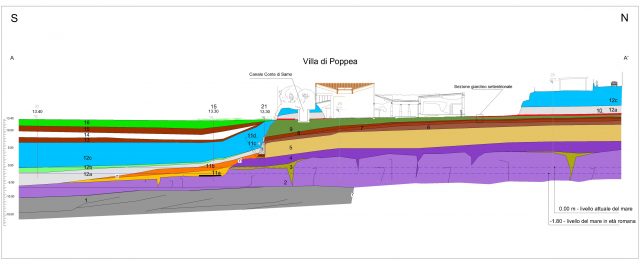

Finally, exciting new geological research has revealed the ancient setting of the Villa. There was one clue, partially explored in the Oplontis Project’s first excavation: a stairway descending from the slaves’ quarters to a tunnel, filled with hardened volcanic ash. Using Ground-Penetrating-Radar, we found anomalies on the south of the Sarno Canal suggesting that the tunnel ended in a stairway leading down some 9 meters. But it was not until geologist Giovanni Di Maio sunk a series of cores between 15 and 30 meters below the modern surface, that we knew that the Villa stood perched on a 14-meter cliff above its own private harbor. In the section, we see that the volcanic material to the north of the Villa, beneath the modern town, also accumulated over the parts pushed over the cliff by the force of the pyroclastic flows.

Oplontis, Villa A. North-south section showing Villa on cliff above sea. Digital rendering. ©Giovanni Di Maio

The remains of other Roman villas that Di Maio has documented remind us of Strabo’s description of the villas and cultivated estates that stretched along the entire rim of the Bay of Naples like one continuous city.

Several features distinguish our 3D model from other similar archaeological initiatives. Since it is based on a first-person shooter gaming engine, Unity©, the user can navigate every space at will—unlike the determined paths of most models. The user can also toggle between actual and restored states, change the lighting systems, and meet other avatars. Most important for its use as a scholarly resource is the fact that by pressing the “Query” button, a researcher can directly access the database for the feature on the screen—whether a wall painting, or the finds in one of our 20 trenches, or the results of isotopic analysis of the marble of one of the 19 sculptures found in the gardens.

Oplontis, view southeast corner of pool and diaeta 78, with several sculptures reset in place. Photo Stanley Jashemski 1978_2_27. ©The Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, The University of Maryland

The original excavations of Villa A at Torre Annunziata aimed to make it into a living museum that the public could visit. This meant creating a new building that looked ancient. Walls had to be rebuilt and colonnades had to be reconstructed to support modern concrete beams, new tile roofs, and reconsolidated fresco fragments. In the process of building this living museum, the pieces of the puzzle that didn’t fit were simply ignored. Today, with digital means, we have put many of those puzzle-pieces back into the Villa.

The 3D model, linked with the database will allow us, and future generations, to find material easily by clicking on find-spots; scholars will be able to share in our work and even add to the information in our database. The model complements the e- book and because the ACLS has graciously offered to make the Oplontis Project publications open access, scholars and laypersons worldwide can benefit from the work of our 42 contributors, coming from wide range of scientific and humanistic disciplines.

A longer version of this article was originally published in Apollo: The International Art Magazine (February 2014), 48-53.

John R. Clarke and Nayla K. Muntasser, Oplontis: Villa A (“Of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy (e-book)

Top image: Oplontis, oecus 15, reconstruction of west wall from fragments, overlay on portion of east wall. Reconstruction by Timothy Liddell. ©The Oplontis Project

Episode 75: The Birmingham Qur’ān

In the summer of 2015, an obscure Qur’ān manuscript hidden in the far reaches of the Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham grabbed attention worldwide when carbon dating revealed that the book was one of the oldest Qur’āns known to exist. In fact, it might have been written during the lifetime of the Prophet Muḥammad … or might it even have been written before Muḥammad’s lifetime?

Guest Christopher Rose (yes, our regular co-host) has been following the headlines and puts the discovery of the Birmingham Qur’ān within the larger field of Islamic and Qur’ānic Studies, and explains how the text might raise as many questions as it answers.

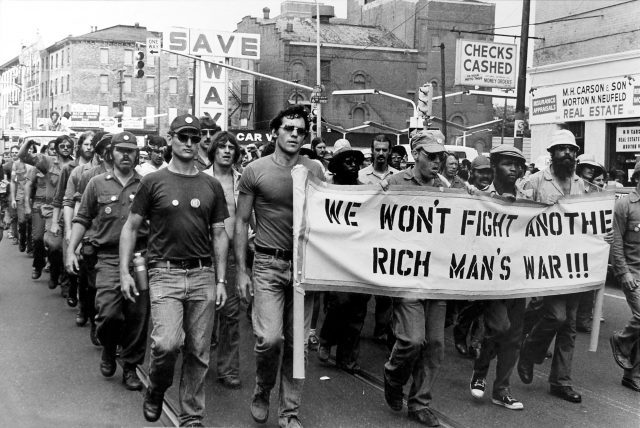

Must Read Books on the Vietnam War

Must must-read books on the Vietnam War

Christian Appy, American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity (2015).

The latest in a long line of studies focused on the legacies of the war in the United States, Appy’s book covers everything from film and literature to foreign and military policy.

Pierre Asselin, Hanoi’s Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965 ( 2013).

Asselin’s book, rooted in extensive research in Vietnamese records, is one of the first to examine the North Vietnamese side of the decisions that led to a major war in 1965. Scholars will no doubt get better access to North Vietnamese materials in the years to come, but this book is an extraordinary accomplishment, shedding light on matters that have defied study for decades.

William J. Duiker, Ho Chi Minh: A Life (2000).

Duiker’s exceptionally engaging biography draws on material from around the world deftly analyzes the blend of nationalism and communism at the heart of Ho Chi Minh’s revolutionary activism.

Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

Logevall’s book is the most influential study on U.S. decision-making during the critical years 1964-1965. It challenges the conventional notion that the U.S. decision to wage a major was nearly inevitable, showing instead that Lyndon Johnson had realistic alternatives to escalation.

Neil Sheehan, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and the America in Vietnam (New York: Vintage, 1989).

Sheehan, an influential journalist during the early stages of America’s war in Vietnam, examines the life and career of John Paul Vann, an American who spent years in Southeast Asia trying to transform South Vietnam into a viable nation capable of defending itself. Vann’s failure captures in microcosm the problems that beset American policy in the area.

The War in Vietnam Revisited

From the editor: This month, we are joining the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin to discuss the Lessons and Legacies of the War in Vietnam. On November 12, 2015, the IHS is sponsoring a roundtable on the subject. It is open to the public and you can find more information here. During the month Not Even Past will continue to post articles about the war in Vietnam and we will post an episode on 15 Minute History featuring Professor Mark Lawrence, who is introducing the subject and some of his research on it, below.

On January 9, 2007, Senator Ted Kennedy stepped to the podium at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., and assessed America’s ongoing war in Iraq in words certain to grab the nation’s attention. “Iraq,” Kennedy declared, “is George Bush’s Vietnam.” The speech came amid ferocious debate in Washington and across the country about the Bush administration’s plan to resolve the war in Iraq, a grueling and bloody affair despite nearly four years of fighting, not by drawing down U.S. troops but through a “surge” in the number of American combat troops in the country. The Massachusetts Democrat insisted that George W. Bush, just like Lyndon Johnson four decades earlier, was responding to frustration by doubling down on a failed enterprise. “In Vietnam,” Kennedy said, “the White House grew increasingly obsessed with victory, and increasingly divorced from the will of the people and rational policy.” In the end, he added, more than 58,000 American died in a quest for unachievable objectives.

A marine from 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, moves an alleged Viet Cong activist to the rear during a search and clear operation (Wikipedia)

A few months later, President Bush responded in kind as he sought to convince Americans to support his escalatory policy Iraq despite the difficulties that had befallen U.S. troops up to that point. In Vietnam, just as in Iraq, Bush asserted, “people argued that the real problem was America’s presence and that if we would just withdraw, the killing would end.” In fact, said Bush, the problem in Vietnam was that weak-willed Americans prevented U.S. troops from using sufficient force and forced their withdrawal before they could achieve goals that were within reach. The result was nothing less than human catastrophe: “One unmistakable legacy of Vietnam,” Bush concluded, “is that the price of America’s withdrawal was paid by millions of innocent citizens whose agonies would add to our vocabulary new terms like ‘boat people,’ “re-education camps,’ and ‘killing fields.’”

Women and children crouch in a muddy canal as they take cover from intense Viet Cong fire at Bao Trai, about 20 miles west of Saigon, Jan. 1, 1966. Paratroopers, background, of the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade escorted the South Vietnamese civilians through a series of firefights during the U.S. assault on a Viet Cong stronghold. (AP Photo/Horst Faas, via Atlantic In Focus)

This debate demonstrates the intensity of the controversies that still swirl around the Vietnam War nearly 40 years after it ended. Why did U.S. leaders escalate American involvement and keep fighting despite the problems they encountered? Was the war winnable in any meaningful sense if Americans had made different decisions about how to wage it? Did U.S. leaders snatch defeat from the jaws of victory by withdrawing American troops in the early 1970s? Scholars and other writers will likely continue to debate these questions for many years to come.

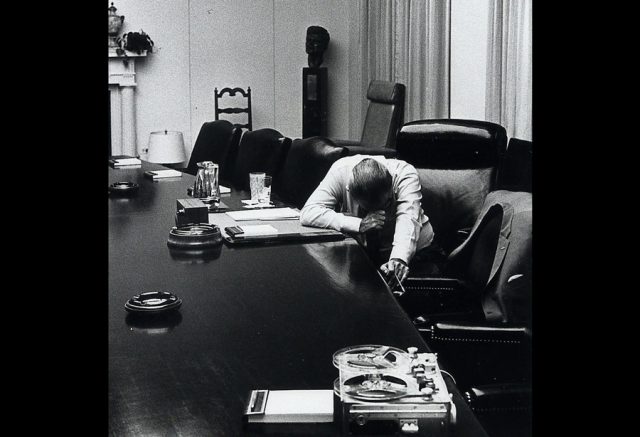

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson listens to a tape recording from his son-in-law Captain Charles Robb at the White House on July 31, 1968. Robb was a U.S. Marine Corps company commander in Vietnam at the time. (Jack Kightlinger/AP via Atlantic In Focus)

The dueling speeches from 2007 also underscore the remarkable relevance of the Vietnam War for American politics and foreign policy in the twenty-first century. Both Kennedy and Bush understood that the war could be a powerful rhetorical device to mobilize Americans by tapping into strongly held views about the reasons for America’s defeat. They recognized as well that the war remained a widely acknowledged point of comparison in the United States for thinking about whether and how to mount military interventions abroad. For some Americans, the main lesson of the lost war is that the United States should be extremely cautious about undertaking military commitments in distant, culturally alien places. For others, the key takeaway is that the United States, once it decides to intervene overseas, must fight with maximum force and see its commitments through to the end. Policymakers will no doubt continue to invoke contrasting lessons of the war far into the future.

Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees crowd a U.S. helicopter which evacuated them from immediate combat zone of the U.S.-Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia on May 5, 1970. They were taken to a refugee reception center at the Katum Special Forces camp in South Vietnam, six miles from the Cambodian border. (Ryan/AP via Atlantic In Focus)

The Vietnam War remains, then, both contentious and important – a subject of great interest for scholars but also a matter of enduring significance in politics and policymaking. Studying the war is both a fascinating intellectual undertaking and a valuable exercise in civic responsibility. Yet exploring the history of the war is no simple task, clouded as that history is by generations of polemics and persistent uncertainty about the motives and objectives of leaders on all sides. And then there is the problem of sheer scale. According to one recent estimate, more than 30,000 books have been published about the war, a number will no doubt grow to even more staggering heights as authors gain access to new sources, especially from repositories outside the United States, and open new lines of inquiry.

My books – Assuming the Burden: Europe and the American Commitment to War in Vietnam (2005); The Vietnam War: A Concise International History; and The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents (2014) – are aimed at both shedding new light on the war and making its history accessible to twenty-first-century readers. The first book, drawing on sources from numerous archives in the United States and Europe, examines the relationship among France, Britain, and the United States between 1944 and 1950, the years when Western governments first came to see it as a Cold War crisis rather than a war of anticolonial resistance. Likeminded policymakers in each of the three key countries made common cause in order to form an international alliance aimed at defeating the revolutionary nationalists headed by Ho Chi Minh.

The second book is a sweeping narrative of the war that, unlike most standard surveys of the subject, attempts to tell the story as an episode not in American history but in global history. It delves into American decision-making and the experiences of ordinary Americans but it also examines the roles of Vietnamese of various political stripes as well as the Chinese, Soviets, and others. The third book collects about 50 primary-source documents reflecting the history of the war from the 1930s until the early twenty-first century. The book, aimed especially at undergraduate students studying the war, is designed to enable readers to draw their own conclusions about controversial matters including the nature of Vietnamese nationalism, the reasons for American anxiety about a communist takeover of South Vietnam, the nature of the South Vietnamese government, the reasons for America’s defeat in Vietnam, and the legacies of the war in the United States and around the world.

Want to read more.? Click here for Mark Lawrence’s must-read books on the war in Vietnam.

Episode 74: The Changsha Rice Riots of 1910

In the waning days of China’s Qing Empire, a riot broke out in Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province. After two years of flooding, a starving woman had drowned herself in desperation after an unscrupulous merchant refused to sell her food at a price she could afford. Three days of rioting followed during which symbols of Qing power were destroyed by an angry mob, which then turned its sights on Changsha’s Western compound. Historians have long assumed the mob was controlled by the landed gentry, but as nearly every dictator knows, a crowd has a mind of its own.

James Joshua Hudson, Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Knox College, describes the riots and some surprising finds he made conducting fieldwork in Hunan that offer a glimpse into the deeply layered tensions on the eve of the downfall of the Qing dynasty.

Episode 73: The Borderlands War, 1915-20

In the early part of the 20th century, Texas became more integrated into the United States with the arrival of the railroad. With easier connections to the country, its population began to shift away from reflecting its origins as a breakaway part of Mexico toward a more Anglo demographic, one less inclined to adapt to existing Texican culture and more inclined to view it through a lens of white racial superiority. Between 1915 and 1920, an undeclared war broke out that featured some of the worst racial violence in American history; an outbreak that’s become known as the Borderlands War.

Guest John Moran Gonzales from UT’s Department of English and Center for Mexican American Studies has curated an exhibition on the Borderlands War called “Life and Death on the Border, 1910-1920,” and tells us about this little known episode in Mexican-American history.

From Yellow Peril to Model Minority

By Madeline Hsu

Both of the books I have written originate with family stories. When I was unable to recognize my parents’ and grandparents’ experiences in standard histories of migration and Chinese Americans, I began digging for more information so I could develop the narratives of their lives on my own. My first book, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and Southern China, 1882-1943, drew upon my personal knowledge. Standard depictions of Chinese Americans during the 1920s and 1930s represented them as groups of dysfunctional bachelors stuck in service sector jobs such as laundries and restaurants. My maternal grandfather might have seemed a typical Chinatown “bachelor” to the casual observer, but his story was more complicated. He arrived in the United States as a teenager in the 1920s to help his father run a grocery store serving African American customers in a small town in rural Arkansas. In the mid 1930s he returned to China, married my grandmother, fathered my mother, and then when money fell short, returned to Arkansas alone due to restrictive immigration laws. On his own and at a distance, he was providing for his family back home.

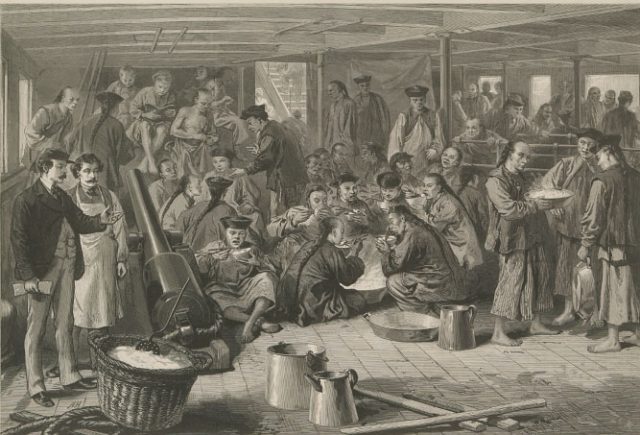

Sketch on board the steam-ship Alaska, bound for San Francisco. From “Views of Chinese,” The Graphic and Harper’s Weekly, April 29, 1876

My grandfather’s story led me to uncover the largely overlooked reality that about 25 to 40 percent of Chinese men living in the United States before World War II were also long-distance husbands and fathers, although to most Americans they looked like non-assimilating oddities living communally with other perpetually single men. Situating such lives in the transnational context of the families and communities that they supported in China, often at great personal sacrifice, gives meaning to the hardships endured by Chinese American “bachelors” who were sharply constrained by open discrimination and the most severe of immigration restrictions during what is known as the Chinese exclusion era (1882-1943).

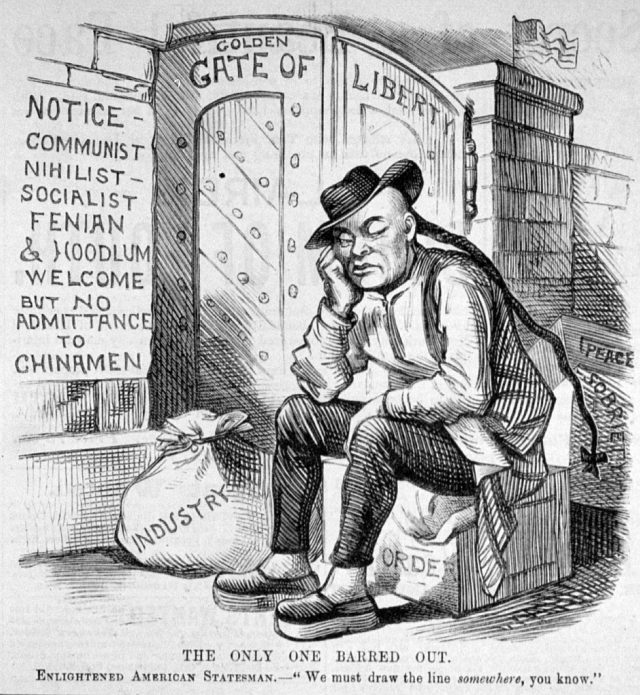

“We must draw the line somewhere, you know.” Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, vol. 54 (1882 April 1).

My second book, The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority traces my father’s immigration story, which also departed from standard narratives. My father arrived for graduate studies in chemical engineering in 1960. Then he managed to convert from student status and gain permanent residency rights, as did over 90 percent of his contemporaries from Taiwan. Although the immigration of educated, professional Asians has become commonplace, this change in migration patterns is usually attributed to the 1965 Immigration Act and its occupational preferences, too late to explain what happened with my father.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Immigration Act, October 3, 1965. (U.S. National Archives, Identifier 2803428)

Seeking answers led me to uncover the longer roots of privileged migrations by Chinese students and intellectuals. I found that even in the throes of the Chinese exclusion era, when most Chinese were barred from entering the United States, could not gain citizenship by naturalization, and lived under some of the most segregated of circumstances if they did gain entry, educated Chinese were welcome on university and college campuses and among internationalist circles that included leaders from foreign policy makers and influential foundations. From the 1910s through the 1930s, Chinese were always among the most numerous of international students in the United States. In fact, many of the foundations of international education policies and institutions developed to secure their educational access and success.

Unlike their working-class counterparts, who were seen as unwanted labor competition and incapable of sharing American democratic values, Chinese intellectuals were seen as members of China’s leadership class and culturally compatible. Educating them in the United States was a friendly, inexpensive, yet effective means of extending American influence over China. These hopes of setting China on the path to American-style democracy and Christianity were most potently embodied by Madam Chiang Kai-shek, the Methodist, U.S. educated (Wellesley 1917) wife of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek who led China from 1927 until 1949. Many less famous, U.S.-educated Chinese also played instrumental roles in establishing the foundations of modern education, professional standards and practices, and government bureaucracies in China.

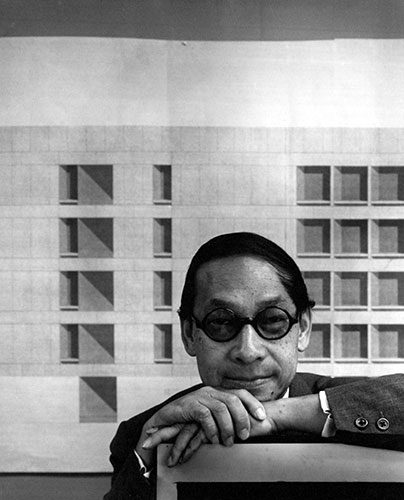

World War II and the Cold War transformed the relationship of Chinese students to the United States by turning them into refugees unable to return to their war-torn, and then communist, homeland. In the case of these well-educated, highly acculturated, and usefully skilled Chinese elites, the international education establishment, State Department, Department of Labor, and Congress found that they could make accommodations to facilitate their remaining in the United States and finding gainful employment. Congress took the unprecedented step of allocating about $10 million to enable the so-called “stranded students” to complete their graduate programs, legally gain employment, and then, through stopgap measures, gain legal permanent residency. Such steps made possible the immigration of such notable Chinese Americans as the architect I.M. Pei and the computer entrepreneur An Wang.

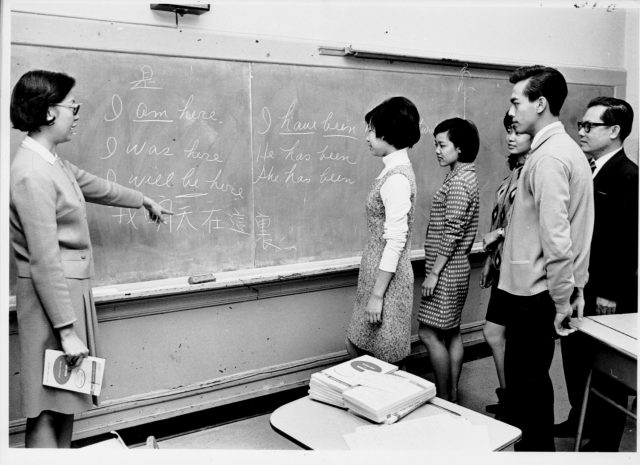

An English class for Asian American ILGWU members of Local 23-25, December 15, 1968 (via Kheel Center on Flickr)

Although numbering only about 12,000, the “stranded students” represented a significant shift in U.S. views of immigration laws and policy that gained force in the two decades leading up to 1965. They demonstrated the benefits of prioritizing economic concerns such as employability and skills in immigration restrictions, rather than the then current law’s primary emphasis on race and national origins which was proving a tremendous stumbling block to foreign policy and retention of the most valued of knowledge workers. If not for such special programs, both Pei and Wang would have been forced to depart the United States.

President and Nancy Reagan at the Opening Ceremonies of Liberty Weekend with medals of liberty recipients Henry Kissinger, Franklin Chang-Diaz, I.M. Pei, Itzhak Perlman, James Reston, Kenneth Clark, Albert Sabin, An Wang, Elie Wiesel, Bob Hope, Hanna Holburn, Lee Iacoccaat Governors Island, New York, July 3, 1986.

Pressures for immigration reforms grew after World War II, as did the numbers of international students with encouragement from the State Department, expanding university systems, and research labs and facilities eager to hire the most talented workers in STEM fields. Provisional measures allowed these international students, many from Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, and South Korea, to work and remain in the United States, until the 1965 Immigration Act permanently enshrined these preferences in law. Since then, a majority of Asian immigrants arriving under its terms have been disproportionately college-educated and based in STEM fields, contributing to the model minority image so much associated now with Asian Americans.

My grandfather and my father don’t appear in my books, but their experiences inspired my research and infuse my broader historical narratives with the gradations of both loss and recuperation characteristic of migrant lives.

Books by Madeline Hsu:

The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (2015)

To read more about Asian American immigration, look here.

You can also hear Madeline Hsu on 15 Minute History.

Top photo credit: Chinese students at MIT, 1944. Courtesy Donald and Sylvia Tsai.

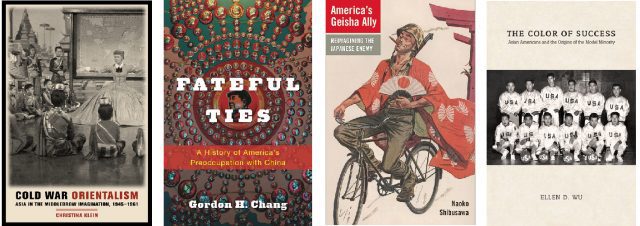

Asian American Immigration: Read More

By Madeline Hsu

Liping Bu, Making the World like Us: Education, Cultural Expansion, and the American Century (2003).

Entwining education, missionary, and international history, Bu traces the overlapping influence of these constituencies in the evolution of international education programs in the United States. The YMCA and the privately run, foundation funded Institute for International Education set the ground rules and institutional practices for fostering international education in the United States with the goal of promoting U.S. influence abroad, agendas and strategies coopted by the Department of State after World War II.

Gordon Chang, Fateful Ties: A History of America’s Preoccupation with China (2015).

Since colonial times, Americans have been fascinated by the promise of great fortune and material prosperity through trade and other kinds of relations with China. Even the discovery of the American continents was driven by the European quest for more direct routes to acquire Chinese silks, porcelains, and tea. China’s ancient civilization attracted admiration even as its seemingly irreconcilable differences drew disdain and contempt. As skillfully depicted by senior historian, Gordon Chang, this love-hate has evolved across several centuries of contested friendship and enmity, and characterizes early 21st century fears and hopes even as China ascends again to world power status.

Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961 (2003).

Klein scrutinizes “middle-brow” American culture at the mid-twentieth-century to reveal how such popular entertainments such as Rogers and Hammerstein musicals, James Michener novels, and Pulitzer Prize winning plays such as “Sayonara” convey U.S. efforts to display and persuade of American integration of Asians and Pacific Islanders and its benevolent domination of the Pacific world.

Naoko Shibusawa, America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy (2006).

This vivid cultural history of the rapid transformation of Japan from America’s deadly foe to best friend in Asia after World War II. American views of Japanese shifted from rejection of male labor competitors and fascist military enemies to embrace of ultrafeminine geishas, wives, and prostitutes stemming from the US military occupation (1945-1952) of Japan. These changing relations produced not only new immigration influxes of war brides and professional class shin issei, but also secured the close economic and political partnership of the two former enemies.

Ellen Wu, The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority (2014).

This comparative study tracks the remaking of outcast Chinese and Japanese Americans after World War II through government programs and media representations that emphasized their positive cultural traits such as family values, hard work ethic, self-sufficiency, and respect for law, even though both communities still faced significant issues such as high rates of juvenile delinquency, under and unemployment, poor health outcomes, and other forms of urban blight. Wu argues that such campaigns to position Asian Americans as “definitely not-black,” in contrast to their pre-war condition as “definitely not-white,” has fed the model minority image as a form of rebuke to minority populations associated with lower levels of attainment.