by Huaiyin Li

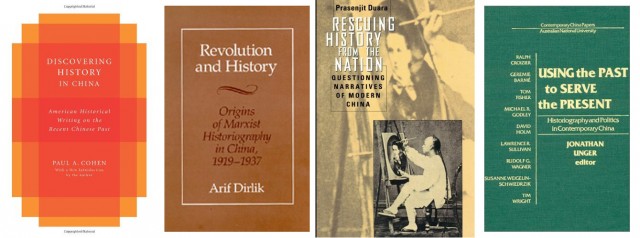

Arif Dirlik, Revolution and History: The Origins of Marxist Historiography in China, 1919-1937 (University of California Press, 1978)

Central to the Marxist historiography in China, according to Dirlik, is historical materialism that serves as a paradigmatic theory shaping the interpretations of premodern and modern China. This book traces the introduction of historical materialism and the rise of Marxist history writing in China to a series of debates on the nature of Chinese society and revolution in the early twentieth century.

Paul Cohen, Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past (Columbia University Press, 1984).

A review of American studies of modern Chinese history, focusing on the impacts of different interpretive frameworks on history writing, including “China’s response to the West,” “tradition and modernity,” and “imperialism.” The book ends with an elaboration of “China-centered history” as a new approach to understanding the Chinese past.

Prasenjit Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China (University of Chicago Press, 1997)

Beginning with a discussion on how the modern nation-state and its powerful ideologies influenced the ways histories are written and understood, the author questions the notion of a progressive, linear history narrating an inexorable drive toward enlightenment. Instead of a single narrative of national history, or the upper-case of history, on the basis of “retrospective constructions to serve present needs,” Duara proposes a “bifurcated history” to reveal that “the past is not only transmitted forward in a linear fashion, its meanings are also dispersed in space and time.”

Jonathan Unger, ed., Using the Past to Serve the Present: Historiography and Politics in Contemporary China (Sharpe, 1993)

A collection of essays that discuss the writings of individual historians and the debates of historical issues in the Mao and post-Mao eras.