In the last years of the twelfth-century, a monk named Engelhard, from the German monastery of Langheim, composed stories about miraculous events and visions he believed his fellow monks had experienced. This was not a decision made lightly: parchment was expensive, the process of writing laborious, and monastic authors needed permission from their superiors to write at all. But Engelhard (and his abbot) considered this project worthwhile. His stories preserved memories of holy monks, celebrated the special sanctity of his monastic order, and encouraged proper behavior. Other monks must have found this collection of stories worthwhile. Over the next century, it was copied – still by hand, still on parchment – at least four times.

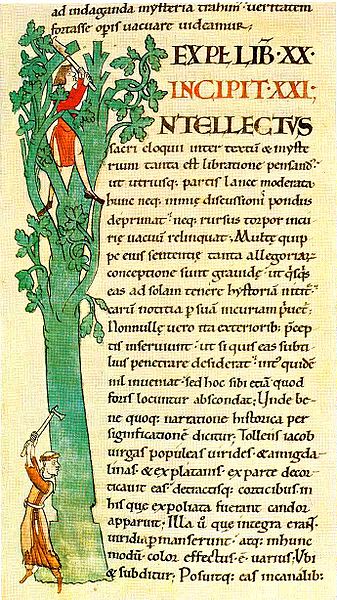

The historical text I present here is one of Engelhard’s monastic stories. I have transcribed it from an early thirteenth-century manuscript and translated it from Latin into English. It contains a striking and unusual image: an apparition of the Virgin holding a vase filled with the sweat she had collected from monks laboring in fields. The image reinforces the purpose of Engelhard’s collection, for Mary praised the monks’ work and the holiness of their monastery; after hearing the story of the vision, Engelhard claimed that the monks worked still harder. However, this story does more than exhort and praise these Cistercian monks. It also illustrates changing attitudes toward labor as Europe moved from a subsistence to a commercial economy.

Engelhard was a monk in the Cistercian order. The first Cistercian monastery was founded in 1098, the same year that the crusaders conquered the city of Jerusalem. Just as the First Crusade demonstrated the combination of technological and economic advances and new religious impulses that allowed Europe to go on the offensive, so the growth of the Cistercian order in the twelfth century also combined a new understanding of religious ideas with technological and economic innovations. These monks sought to follow, as closely as possible, the strictures of the monastic rule written by St. Benedict 600 years earlier. One result of their adherence to the Benedictine Rule was that they rejected the economic practices of their monastic contemporaries, most of whom lived off the labor of a subject peasantry. The Cistercians instead wanted to live off their own labor; they refused gifts of manors and peasant revenues and, as a result, accumulated pasture, waste, and other territory not already settled by peasants. As the monks cleared these lands, raised sheep and pigs, and created workshops for metallurgy and other crafts, they quickly became participants in a new commercial and money-based economy.

The Cistercians’ attitudes toward work did not change as quickly as their economic practices. Medieval society inherited two sets of ideas about work, both of which held work in low esteem. The classical tradition of ancient Greek and Rome valued a cultured leisure and disdained the labor of those who made this cultured leisure possible. The early Christian interpretation of Genesis emphasized that God condemned Adam and Eve to toil and pain and presented labor as a result of human sinfulness. Throughout much of the middle ages, peasants were often seen as cursed by God because they had to labor in order to survive. When the Cistercians monks included agricultural work in their monastic customs, many of their contemporaries were puzzled to see aristocratic men working as peasants: “How, truly, is it religion to dig the ground, to cut down trees, to haul manure?” critics asked.

Even the early Cistercians still viewed labor as a penance for sin. They saw their willingness to take on the work of peasants as teaching them humility and control over their bodies: work was a means of imitating the humility and suffering of Christ, not a way to produce goods for consumption and sale. Soon after the foundation of their order, the Cistercians recognized that it was difficult to combine their prescribed hours of prayer with the demands of an agricultural economy; they may also have realized that aristocratic monks were not skilled at tending sheep and harvesting grain. As a result, they formed a second group of monks within their communities. These “laybrothers” spent less time at prayer and more at work, and they were probably responsible for the economic success of many Cistercian communities.

Engelhard was not the only Cistercian to tell a story about an apparition of the Virgin Mary who encouraged Cistercian labor. There are versions in other Cistercian story collections, but these depict Mary visiting the monks while they are at work, and they emphasize the wonder of seeing such noble men toiling as peasants in the fields. They emphasize labor as a form of penance which has a spiritual value only if it has been chosen voluntarily. Engelhard’s story is different, and suggests a changing attitude toward work. The monk in his story was the cellerar – the official in charge of the laybrothers, of paying hired workers, and generally maintaining the economic well-being of the monastery. And, in Engelhard’s version, this cellerar asks the apparition whether work done out of necessity has the same spiritual value as that done voluntarily. Mary’s response is remarkable: she says that she values both forms of labor and both will receive a reward.

Engelhard’s story suggests a growing recognition of the economic value of work. His ideas are akin to those of other late twelfth-century authors who rejected the idea that those who toiled out of economic necessity were cursed by God, who began to value the involuntary labor of peasants, and who started to quantify both time and production. We are not yet observing a society in which goods are valued primarily by their market worth: Engelhard’s story depicts monks producing sweat for Mary to collect rather than commodities to sell. But Engelard’s story of a monastic vision demonstrates that European attitudes toward work had started to change in tandem with the rise of a new commercial economy in the high middle ages.

A Monk’s Vision of the Virgin Mary (translated by Martha G. Newman)

This event happened in a monastery of our order, in a monastery that is renowned throughout France. Everyone believes it, because the man who saw it has many witnesses to his testimony.

It was harvest time, and as the monks worked in the fields, they sweat heavily with the hard work and under the heat of the day. When evening came, they went to bed and closed the door to their dormitory. The cellarer was a holy man, wise and mature, and of such good character that he alone was allowed to remain outside to take care of the hired workers. When he was finished, he went in to go to sleep, but the door to the dormitory was closed. What should he do? Beat on the door? He was not willing to knock, because the monks were resting. Should he then leave? But then he himself would have no rest. Preferring to inconvenience himself rather than his brothers, he entered the chapter room and sat on the steps.

But he did not sleep, and behold! the young woman entered, her light preceding two other women, and she approached the monk and asked if he slept.

He responded that he was awake, but asked why, against all monastic custom and in the middle of the night, the women entered the monastery without a care.

The woman said, “I am Mary, who cares for all who are in this abbey and in this order.” She carried a glass vase, which she held to her nose as if capturing the smell from it. And she said, “ I have visited today my monks in the field, and I collected their sweat for myself in this vase. For me it is the most pleasant smell, and it is certainly worthy for my Son, and it will return the highest reward.

The monk then asked, “O holy Lady, how important is our labor for you which is not so much done from voluntary devotion as from the necessity of our poverty?”

And she answered, “What do you say? Have you not heard that what is voluntary receives a penalty and duty earns the reward? If duty receives the reward, what is voluntary now receives a part. But whether out of necessity or voluntary, what you do is mine. I claim all of your work for myself, and what I receive, I remunerate.”

Having said this, she disappeared, and the monk slept sweetly, thus refreshed in hope, comforted in faith, and willing to work.

When morning came, he joyfully and devotedly reported what he had seen to the abbot at the chapter meeting. All were joyful, all believed him, and no one doubted it because of the seriousness of his character. All were stirred up, each was aroused to work. They labored and they sweated in such a manner that Mary, as she came near, could fill up her vase.

And thus Mary was accustomed to sport sweetly with her sons; thus she showed herself in a vision to them, offering them the gift of peace and grace. Those who were meek heard and rejoiced, those who were discouraged heard and were comforted; the lazy were inspired; all ran easily and without exhaustion to give glory to Christ and Mary, and from them receiving grace.

From Engelhard of Langheim’s Miracle Book. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 13097, ff. 145v-146r.