Episode 116: Jewish Life in 20th Century Iran

The past is never dead. It's not even past

Between 1910 and 1920, an era of state-sanctioned racial violence descended upon the U.S.-Mexico border. Texas Rangers, local ranchers, and U.S. soldiers terrorized ethnic Mexican communities, under the guise of community policing. They enjoyed a culture of impunity, in which, despite state investigations, no one was ever prosecuted. This period left generations of Texans with a deep sense of injustice, and representations of this period in popular culture still celebrate police violence against ethnic Mexicans. Yet families fought back, demanding justice for atrocities against Mexican-American communities.

Guest Monica Martínez of Brown University joins us today to discuss what happened on the Texas border a hundred years ago. She also reveals the striking similarities of the period to the Trump administration’s November 2018 decision to send military troops to the border.

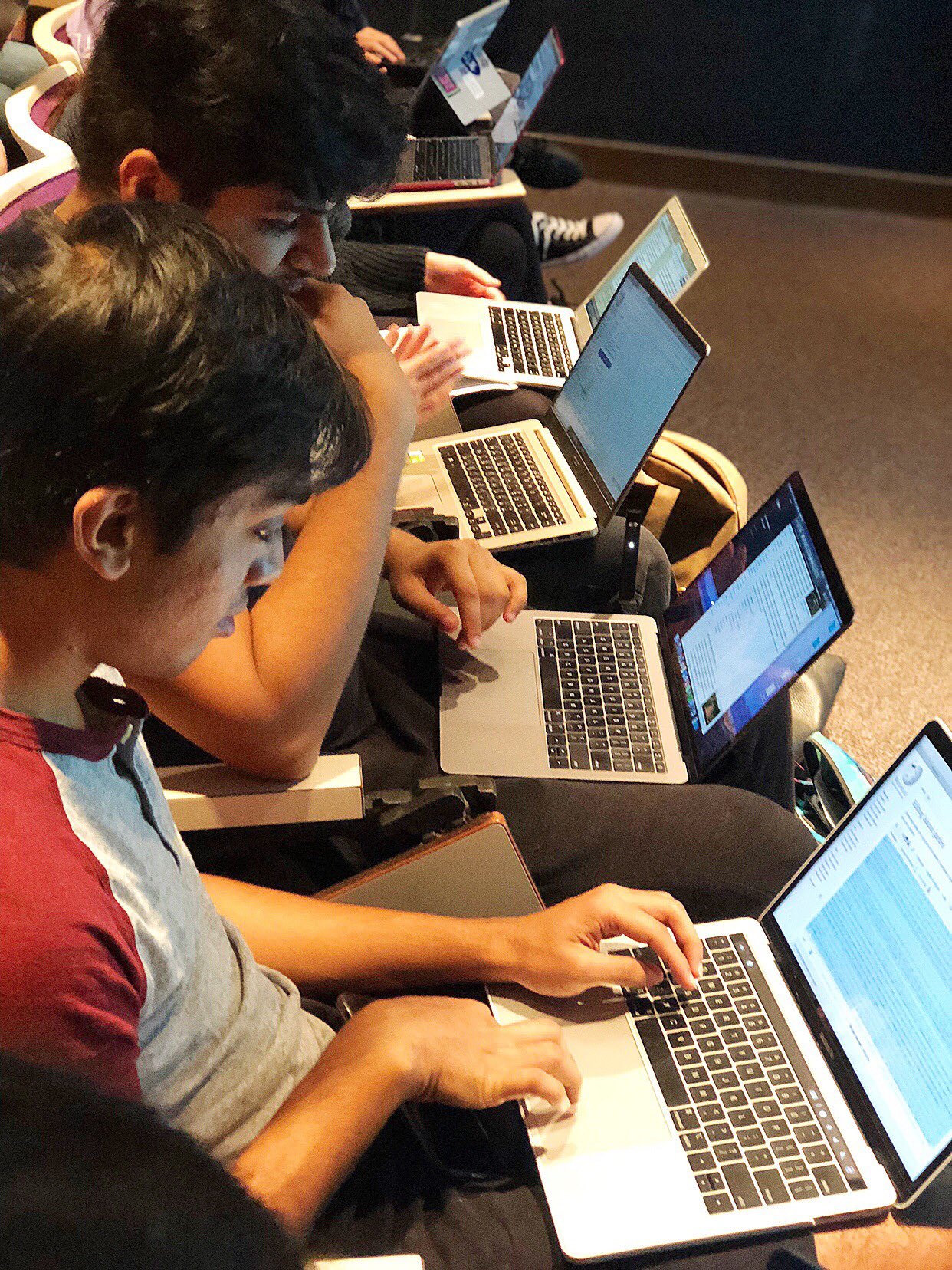

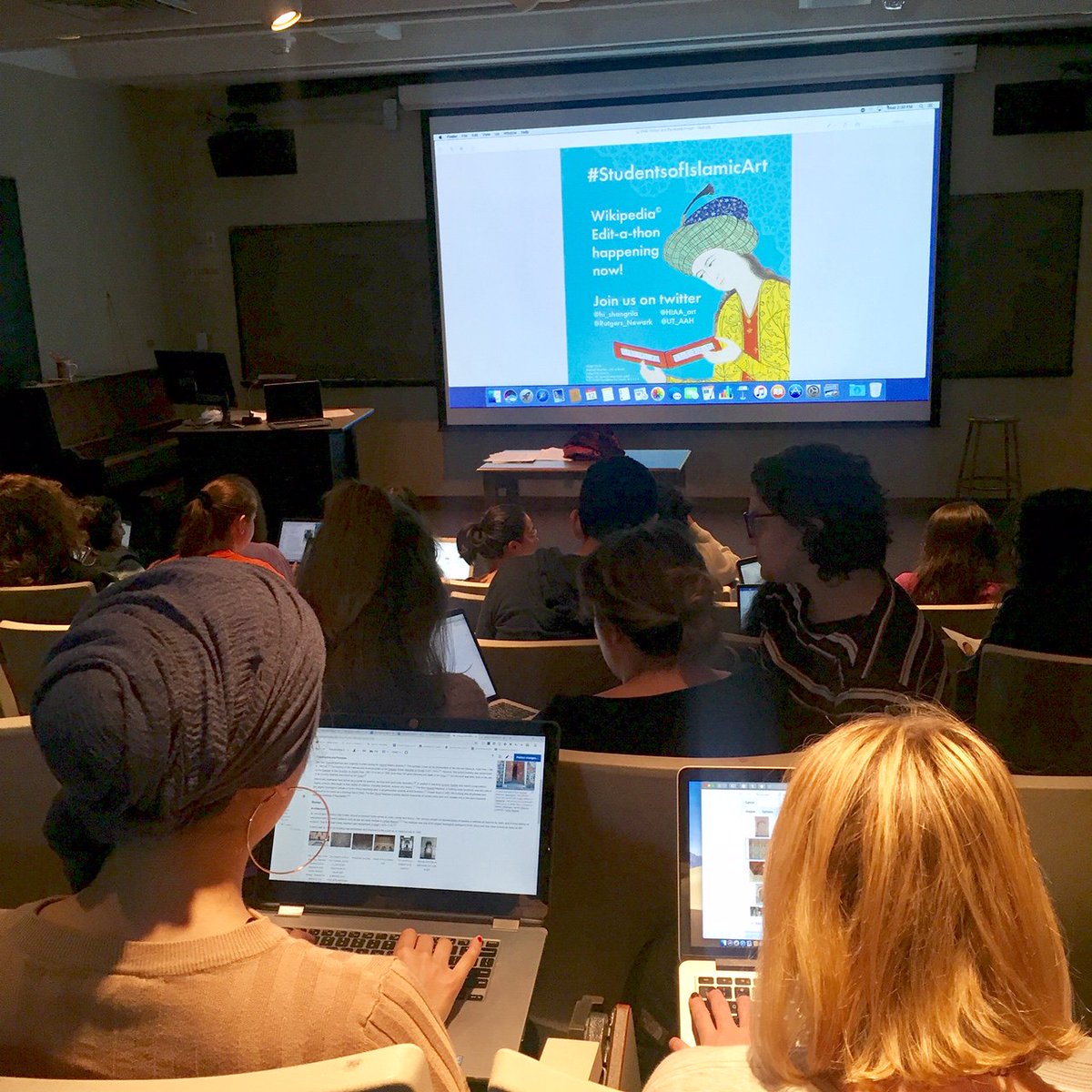

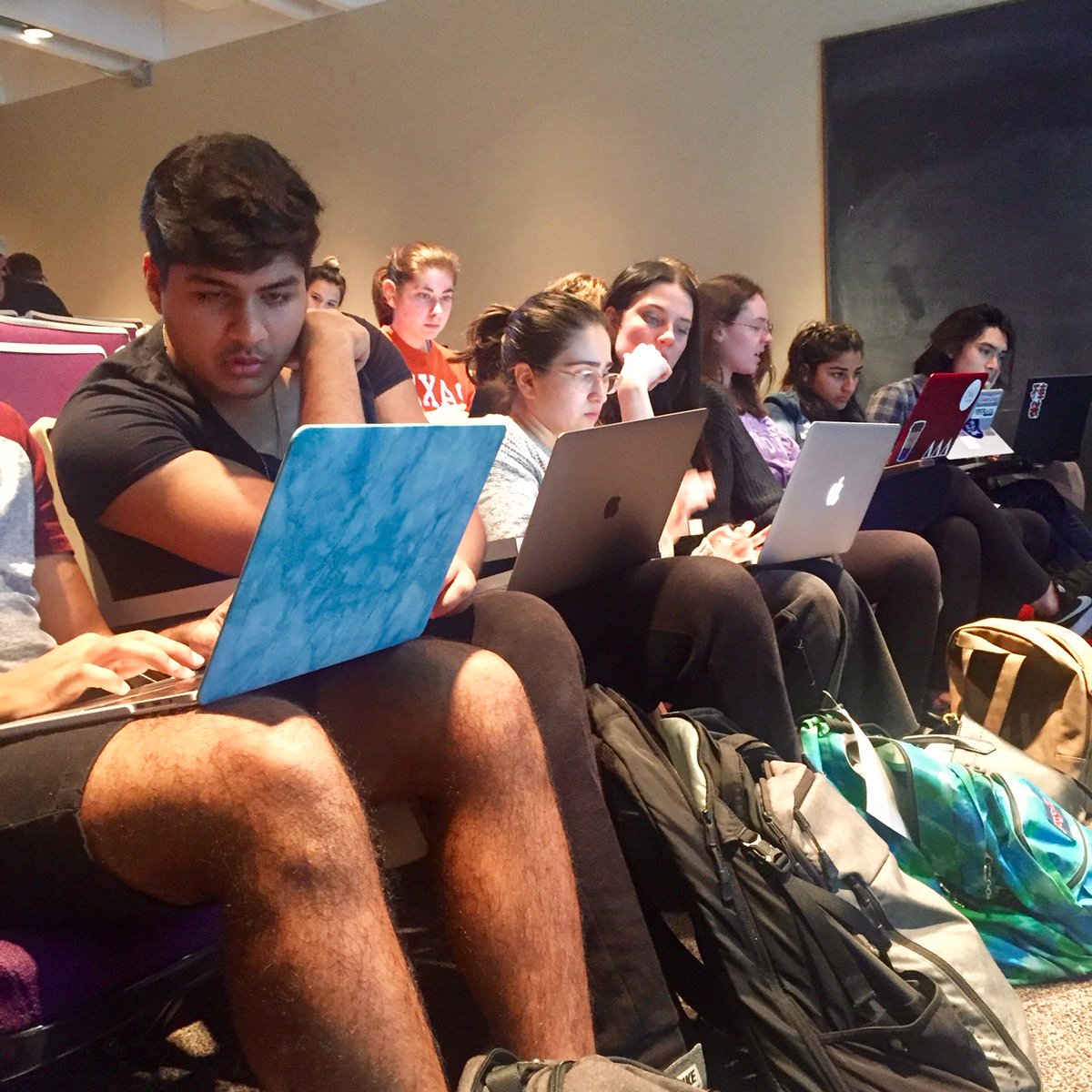

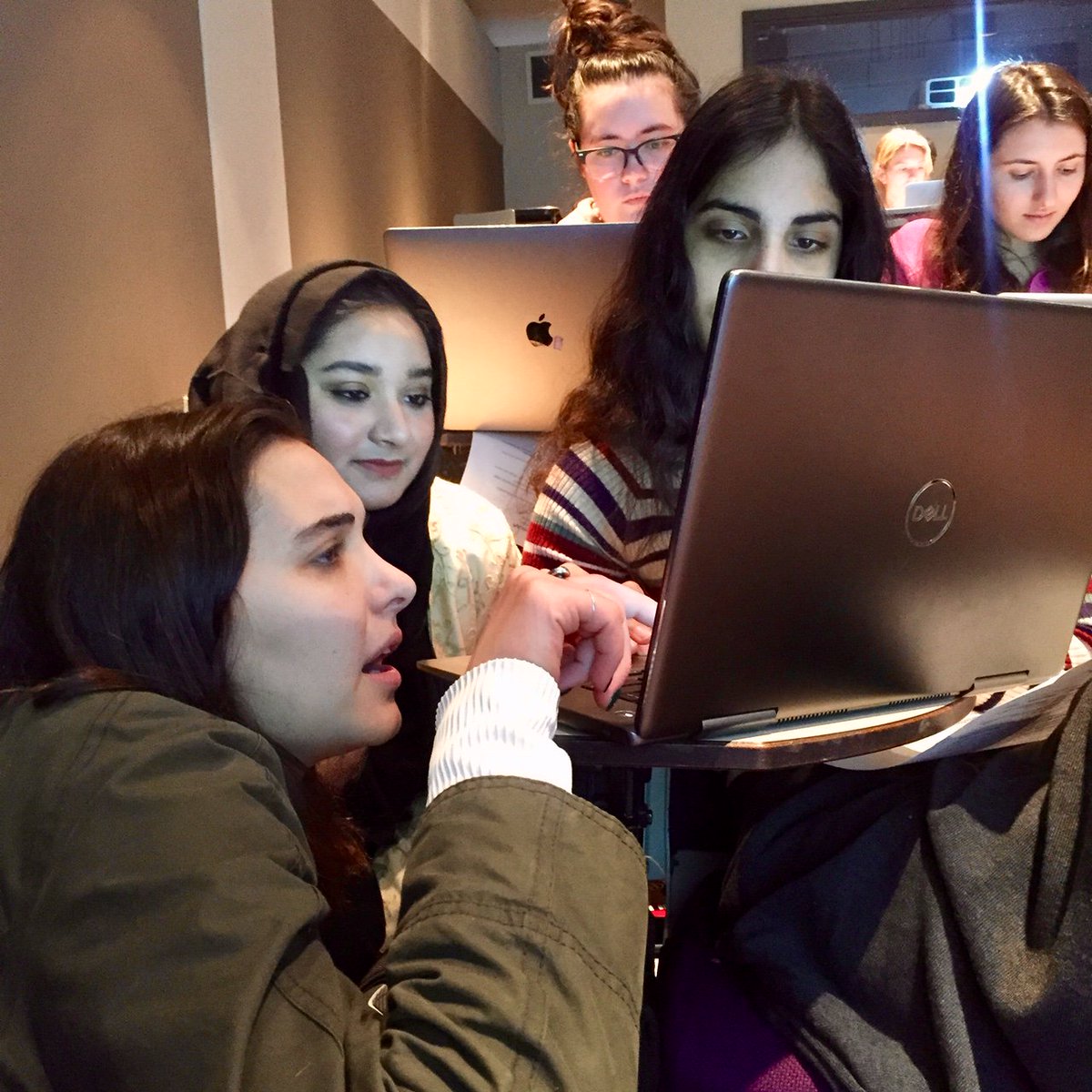

This semester in my Arts of Islam survey, I decided to scrap the research paper and have students collaborate to re-write @Wikipedia articles. It ended up better than I could have imagined & transformed how I think about teaching #StudentsOfIslamicArt #IslamicArt #MedievalTwitter

I was hesitant about shaking up a popular class that had worked well for years, but one statistic finally convinced me: 90% of Wikipedia articles are written by men – and largely by men from Euro-American contexts.

Zain Tejani and Tarik Islam improving the article on Islamic Gardens by replacing some of the more subjective aspects of the pages on the Islamic gardens with entries on the surviving gardens and sensorial experience. They later found their edits reverted by another editor – a valuable lesson about how to work within Wikipedia’s editor community (they’re still in negotiations on the Talk page!)

And on Not Even Past, a feature on Dr. Mulder’s award-winning book: Carved in Stone: What Architecture Can Tell Us about the Sectarian History of Islam

By Sabine Hake

The “proletariat,” imagined to be the most radical, organized, and active segment of the working class, never existed as more than a utopian concept, but it had a profound effect on German society from the founding of Social Democracy in 1863 to the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933. Over the course of seventy years, the idea of a proletariat, often simply equated with the working class, inspired countless treatises, essays, novels, songs, plays, dances, paintings, photographs, and films. All of these works shared the vision of a classless society, conveyed the importance of class unity and solidarity, and, in very concrete ways, contributed to the making of class consciousness. Some of the figures are familiar to scholars of German culture and politics, including Ferdinand Lassalle, Karl Kautsky, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Wilhelm Reich, John Heartfield, and Bertolt Brecht. However, the vast majority are unknown working-class poets, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. Today largely forgotten, dismissed, or ignored, these men (and they were mostly men) insisted on the workers’ right to be heard, seen, and recognized. At the time, their contributions gave rise to a rich and diverse culture of political emotions, attachments, commitments, and identifications. Today, these works offer privileged access to the social imaginaries that formed during a crucial period in the history of mass political mobilization. In particular, they reveal what it meant—and even more important, how it felt—to claim the name “proletarian” with pride, hope, and conviction.

Some of the figures are familiar to scholars of German culture and politics, including Ferdinand Lassalle, Karl Kautsky, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Wilhelm Reich, John Heartfield, and Bertolt Brecht. However, the vast majority are unknown working-class poets, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. Today largely forgotten, dismissed, or ignored, these men (and they were mostly men) insisted on the workers’ right to be heard, seen, and recognized. At the time, their contributions gave rise to a rich and diverse culture of political emotions, attachments, commitments, and identifications. Today, these works offer privileged access to the social imaginaries that formed during a crucial period in the history of mass political mobilization. In particular, they reveal what it meant—and even more important, how it felt—to claim the name “proletarian” with pride, hope, and conviction.

The workers’ demands for representation were part of larger political struggles associated with the worker’s movement and the working class, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (the SPD) and the German Communist Party (KPD). Given its formative emotional qualities, however, the proletarian imaginary cannot be dismissed as a mere function of party politics or political ideology. In ways not yet fully recognized, attachment to the figure of the proletarian became the basis of a vibrant alternative public sphere and a thriving socialist culture industry. Moreover, the countless stories and images of pride, hope, fear, rage, joy, and resentment made the worker a compelling figure in larger debates about modern class society and mass politics and contributed to the workers’ remarkable availability to socialist, nationalist, and populist appropriations. Marxist thought may have provided important concepts and theories but the enormous archive of emotions produced in the name of the proletariat forces us today to move beyond ideology critique—and to recognize the power of political emotions and of emotions in politics beyond traditional left-right distinctions.

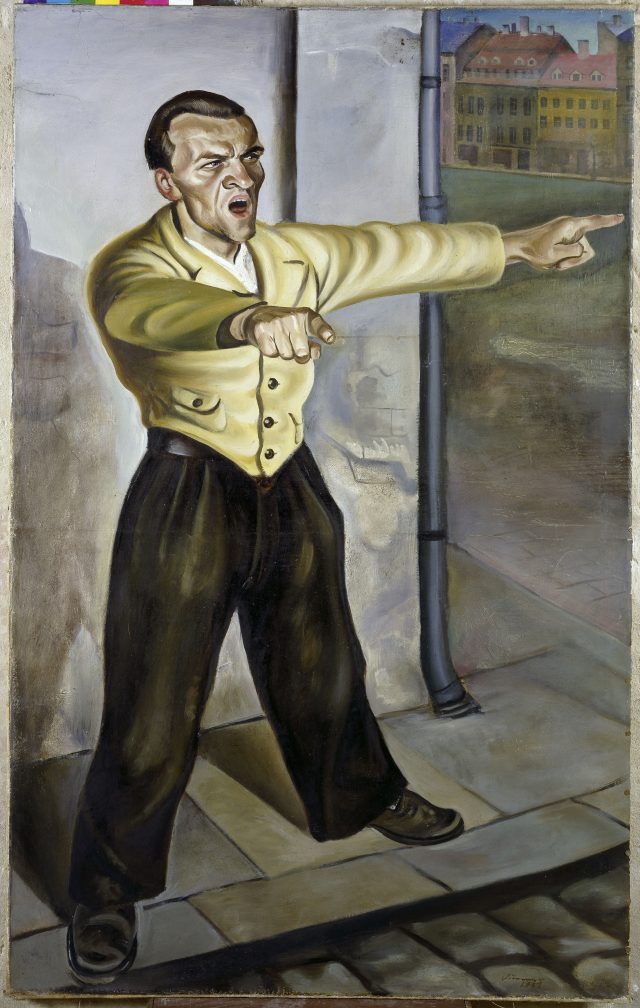

To give a sense of the scope of this “proletarian” cultural output, let’s take a few examples. The ubiquitous workers’ song books offered compelling models, from the Workers’ Marseillaise to the Communist International, for singing, feeling, and thinking in unison as workers. The Lutheran pastor Paul Göhre edited workers’ life writings with a view toward facilitating cross-class understanding that made workers’ emotions legible to bourgeois readers. Socialist party leaders, like August Bebel spoke about socialism as an emotional experience by describing his attachment to socialism in surprisingly sentimental terms, while Karl Kautsky railed against the dangers of emotional socialism. Kinderfreunde groups, started during the 1920s, organized summer tent cities where working-class children already practiced living in a classless society, in part to help them overcome feelings of inferiority. Communists modeled proper physical and, by extension, political stances, in the Rotes Sprachrohr troupe (Red Megaphone), which used a hard, rigid way of speaking, standing, and moving to equate class struggle with militant masculinity. And communist groups became involved in the sex reform movement and other radical initiatives through the work of Wilhelm Reich, who saw proletarian revolution and full genital health as mutually supportive goals.

Curt Querner, The Agitator (1930). An example of the habitus of militant masculinity favored by the German Communist Party (oil on canvas, Nationalgalerie Berlin. Copyright 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst Bonn).

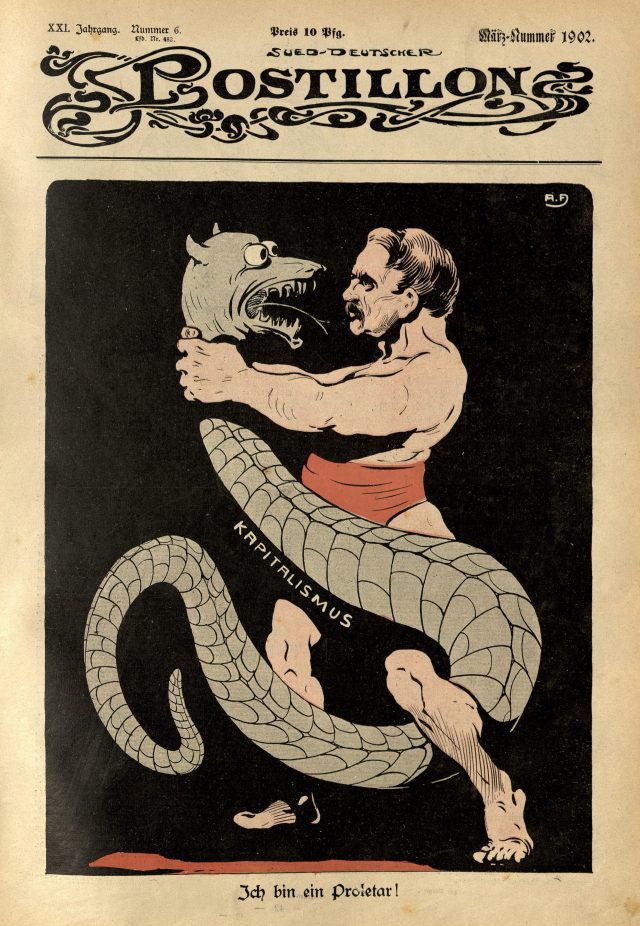

Aesthetic elements of these works were critical in the making of political emotions. For instance, a strong affinity between melodrama and the proletarian imaginary were represented by the aestheticization of suffering. Personified by the proletarian Prometheus, melodrama prepared the workers for the real hardships of class struggle. Socialist writers of working-class versions of the classic coming of age story, or bildungsroman, made character identification the most powerful vehicle for Bildung in the standard sense of education and in the Marxist sense of class formation. And in the work of the photo-montagist, John Heartfield, modernist techniques could give rise to distinctly proletarian structures of life and create an incubator for revolutionary action by making the violence inherent in montage.

Cover of the journal Süddeutsche Postillon (21:6 1902), with the ideal-typical worker fighting the dragon of capitalism. (Ich bin ein Proletar!/ I Am a Proletarian!,” (With permission of Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin.)

While German Studies continues to neglect questions of class, a phenomenon worthy of further commentary (given the German contribution to Marxism and communism), The Proletarian Dream provides the first comprehensive overview of German working-class culture. Is is also is the first account of the culture of socialism that insists on freeing the culture of the workers’ movement from the fetters of ideology critique and recognizing its close connection to popular culture, mass culture, and the culture industry.

As a scholarly subject, the proletariat today may be considered outdated, irrelevant, and slightly peculiar. For me, its alleged obsolescence only confirms what Alexander Kluge once said about his reasons for writing about the proletariat—namely, that it is important not to “allow words to become obsolete before there is a change in the objects they denote.”

Sabine, Hake, The Proletarian Dream—Socialism, Culture, and Emotion in Germany, 1863-1933 (2017).

Several recent monographs in other disciplines address very similar questions in different contexts. The changing meanings of the proletarian in nationalist, regionalist, and anti-colonial movements are particularly obvious in Latin America and Southeast Asia and confirm the centrality of culture, including folk and popular culture, in generating political emotions and forging proletarian identifications:

John Lear’s 2017 book, Picturing the Proletariat, Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940 , highlights the ways radicalized workers in Mexico drew on indigenous traditions (e.g., Posada’s use of folk traditions in political printmaking) and internationalist iconographies (e.g., the proletarian Prometheus in the German socialist press) to support the struggles of workers in agriculture and industry.

Samuel Perry’s 2014 book, Recasting Red Culture in Proletarian Japan: Childhood, Korea, and the Historical Avant-garde, reconstructs the proletarian moment through the communist appropriation of Japanese woodblock techniques, the didactic goals of proletarian children’s literature, and the political avant-garde’s complicated relationship to their country’s imperialist practices.

Sunyoung Park’s 2015 book, The Proletarian Wave: Literature and Leftist Culture in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 offers the corresponding Korean perspective, which includes close attention to the conditions of socialist revolution in rural societies and the unique contribution of socialist women writers.

Photo credit: Agitprop performance by the Red Megaphone Troupe (Grupa Rotes Sprachrohr).

Many American Indian cultures, like the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians, practiced a form of non-hereditary slavery for centuries before contact with Europeans. But after Europeans arrived on Native shores, and they forcibly brought African people into labor in the beginning of the 17th century, the dynamics of native slavery practices changed. Supporting the Confederacy during the Civil War, how did traditional native slavery transform in the Indian Territory throughout the 18th and 19th centuries into something resembling the unchangeable enslavement system of the American South?

Guest Nakia Parker joins us to discuss the African American slave-holding practices of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians during the 19th century, tells us how this system evolved, and reveals the claims to tribal citizenship from this enslavement persisting to the present day.

The year 1968 was a momentous and turbulent year throughout the world: from the Prague Spring and the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, to the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F Kennedy, to the Tet offensive and the surprise victory of Richard Nixon (possibly the most normal thing that happened all year). Apollo 8’s trip around the moon is said to have saved the year from being all bad news.

Guest Ben Wright has helped curate an exhibition on 1968 at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History called The Year the Dream Died, and discusses why 1968 looms large in our collective memory.

By H. W. Brands

When Benjamin Franklin left the Constitutional Convention in September 1787, he was approached by a woman of Philadelphia, who asked what the deliberations of Franklin and his colleagues had given the young nation. “A republic,” he said, “if you can keep it.

Henry Clay was ten years old that summer. He didn’t learn of Franklin’s challenge till later. But when he did, he discovered his life’s work. Clay and others of the generation that followed the founders confronted two problems in particular–two pieces of public business left unfinished in the founding.

The first was the awkward silence of the Constitution on the fundamental question of the federal system: when the national government oversteps its authority, how is that government to be restrained? Must the states obey laws they believe to be unconstitutional? Put most succinctly: where does sovereignty ultimately lie–with the states or with the national government?

The second problem was the contradiction between the equality promised by the Declaration of Independence and the egregious inequality inherent in the constitutionally protected institution of slavery. Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “all men are created equal” was not repeated in the Constitution, but it provided the basis for American republican government, which the Constitution embodied and proposed to guarantee. Slavery made a mockery of any claims of equality.

For forty years Clay wrestled with these challenges. In the golden age of Congress, when the legislative branch retained the primacy intended for it by the founders, the silver-tongued Kentuckian had no equal for adroitness and accomplishment in the Capitol.

But he had some doughty rivals, two in particular. John Calhoun started out as a champion of federal authority, alongside Clay. But as Calhoun felt that authority weighing more and more heavily upon South Carolina, his home, he swung to the opposite pole, becoming the chief theorist of states’ rights.

Daniel Webster did the reverse. Amid the War of 1812, which sorely punished the commerce of New England, Webster proposed that if the pain became too great, the states of his region should reconsider their attachment to the Union. Yet before his career ended, the Massachusetts senator would be hailed as the Union’s most eloquent defender.

Clay, Calhoun, and Webster were the celebrities of their era. Politicians and civilians alike hung on their words. When one or another of the three was scheduled to speak in the Senate, Washington suspended business to listen. Clay’s defense of a protective tariff displayed a sophistication that wouldn’t be exceeded even two centuries later. Calhoun’s construction of state sovereignty persuaded eleven states to bolt the Union in the early 1860s. Webster’s rejoinder of national sovereignty was committed to memory by generations of schoolchildren.

They were called the “the Great Triumvirate” for the influence they wielded upon their fellow legislators. Clay earned a special sobriquet–”the Great Compromiser”–for his ability to pull the country back from the brink of disaster. Three times the Union approached the precipice: when Missouri’s admission compelled a reckoning over slavery in the western territories, when South Carolina vowed to secede if forced to pay a tariff it loathed, and when gold-rush California demanded a state government that forbade slavery.

In each case Clay crafted a compromise that preserved the Union. The last compromise, of 1850, was his masterwork, a fugue in eight parts that balanced the diverging interests of North and South. The effort exhausted Clay, already suffering from consumption, or tuberculosis. He died a short while later. Calhoun had died amid the debate over the compromise, of the same illness. Webster died soon after Clay, of complications from a carriage accident.

With their passing died the spirit of compromise that had enabled them to meet Franklin’s challenge. The spiritual sons of Calhoun made a fetish of states’ rights, especially the right to own slaves. When the Union-revering sons of Clay and Webster–most notably Abraham Lincoln–resisted the Calhounian interpretation of the Constitution, the country descended into civil war.

The war placed an outer bound on each of the twin problems Clay’s generation inherited from the founders, but it didn’t resolve either one. The Union victory effectively forbade secession, but it left lesser assertions of states’ rights tenable. The war-enabled Thirteenth Amendment proscribed slavery, but it said nothing about other inequalities that continued to vex republicanism.

A century and a half later, we still grapple with these problems. States argue with and sometimes sue the federal government over voting rights, abortion, health care, education, the environment and other issues. Inequalities of race, wealth, and opportunity sabotage our efforts to cultivate an inclusive democracy.

In the age of Henry Clay, the deepest divide in American political life was between sections: North and South, Today it is between political parties. But the spirit of compromise–of acknowledging the legitimacy of opposing views, and recognizing the need to incorporate them into law and policy–that allowed the Union to endure during Clay’s lifetime is no less necessary in our time.

Can we keep the republic? The task never ends.

H. W. Brands, Heirs of the Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants (2018) tells the full story of the overlapping lives and careers of Clay, Calhoun and Webster.

For more on this period, take a look at:

H. W. Brands, Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, (2006).

A biography of the general and president whose dying regret was that he hadn’t hanged Calhoun and shot Clay.

Merrill Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, Calhoun, (1988).

It has for three decades been the standard account of the powerful trio. It is now superseded (Brands hopes) by Heirs of the Founders.

Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, (2006). It casts the travails of the era in the context of the emergence of democracy as a transformative mode of politics, economics and culture.

Library of Congress guide to the Compromise of 1850

On November 27, 1978, Harvey Milk and George Moscone were murdered in San Francisco’s City Hall. Milk was one of the first openly gay politicians in California, and his short political career was not only emblematic of the wider gay liberation movement at the time, but his death and legacy inspired a new generation of activism which was seen not only during the 1980s AIDS crisis, but has lingering impacts four decades later.

In this episode, we are joined by Lisa L. Moore from the University of Texas’s English Department and incoming chair of the new LGBTQ Studies portfolio program, to discuss the legacy of Harvey Milk on the 40th anniversary of his assassination.

Not Even Past will publish letters to the editor with educational or scholarly merit. When the letter concerns a post on Not Even Past, the author of the article will be invited to respond. We encourage letter writers to refrain from ad hominem discourse.

—Joan Neuberger, Editor.

Having designed a class that engages students with original texts surrounding the Meusebach-Comanche Treaty, I read Jesse Ritner’s contribution with great interest. He makes valuable observations about the political position of the Comanche, and attempts to take on the Native American perspective which happens far too seldom. I believe, however, that we should recognize the significance of the Treaty of Fredericksburg.

Germans in 1847 did not see themselves as “Anglo-European” settlers. Accordingly, Meusebach launched his expedition without consent of the government (Neighbors and the Delaware followed him), arranged for his own Mexican translator and designated a German Indian agent who remained with the Comanche. The effect was interesting. In a quote attributed to Penateka chief Kateumsi, he finds the Germans to be “less reserved” than the Americans.[1] The Penateka also noticed other cultural differences. A Houston newspaper of May 1847 reads: “[The Comanche] say they are more willing for the Germans to settle in their country than the Texians, for the former settle in towns and villages and do not scatter over the countryside and kill the game as the Texians do.”[2] Money was never the only consideration.

As a German freethinker, Meusebach brought a very exceptional view to Texas. None of his letters indicate he wanted a military solution. It is true that the “Comanche did not forfeit land rights in the treaty.” But he had no expectation that they should. Meusebach suggested a treaty of integration, not of separation. Engraved in the treaty was the spirit of the idealistic European revolutions of 1848. During a speech delivered at the negotiations, Meusebach exhibited racial sensibilities that differed radically from his contemporaries. He suggested intermarriage between Germans and the Comanche, spoke of the unimportance of skin color and mused about young Germans learning the Comanche language.[3]

One of the first settlements in the grant area was founded by German Forty-Eighters. Among the group was a doctor named Ferdinand Herff who successfully performed cataract surgery on a Comanche chief.[4] The episode further strengthened trust. Evidence that Germans were viewed favorably for a few years also comes from a travel account by Friedrich Schlecht from 1848. When he encountered a band of Comanche, the chief shared coffee with him, and told him that had he been of “those who […] had broken their treaties on numerous occasions” he would not have hesitated to scalp him.[5] The Comanche not only understood geopolitics, they also recognized differences in ethnicity and attitude among those they dealt with.

Whether the treaty remains unbroken is a different question. As Roemer predicted, violence erupted as early as 1850.[6] The significance of the treaty, however, and the reason it is still celebrated by Comanche and German descendants, is that it points to a conceivable alternative to the ethnic cleansing of most Native Americans from Texas territory that eventually occurred.

David Huenlich, Research Fellow, Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Zentrale Forschung, (Ph.D. UT Austin, 2016)

[1] Penninger (1896), Fest-Ausgabe zum 50-Jährigen Jubiläum der Gründung der Stadt Friedrichsburg, p. 91

[2] Daily Telegraph and Texas Register [Houston, TX], Monday, May 10, 1847

[3] Penninger (1896), Fest-Ausgabe zum 50-Jährigen Jubiläum der Gründung der Stadt Friedrichsburg, p. 104f

[4] Handbook of Texas Online, Glen E. Lich, “BETTINA, TX,” accessed October 22, 2018, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hvb55

[5] Schlecht (1851), Mein Ausflug nach Texas, p. 74

[6] Wurster (2011), Die Kettner Briefe, p. 19f

I would like to thank David Huenlich for his thoughtful response to my article on the Meusebach-Comanche Treaty of 1847 and the “Lasting Peace” monument that commemorates it in Fredericksburg, Texas. I appreciate his insight into the role of the Indian Agent, R.S. Neighbors. Neighbors was sent by the governor of Texas specifically to stop the treaty, if possible, and to mitigate any negative effects that might have occurred if the treaty could not be stopped. The goals of the German-Texans were certainly at odds with the goals of the Anglo-Texans and U.S. Government, which was precisely why Meusebach needed to make a treaty with the Comanche. In addition, I never intended to question Meusebach’s role as a “German free thinker.” However, the evidence that Huenlich presents in his discussion of Meusebach’s speech during negotiations, should be read with caution. The reliability of information on his speech is difficult to determine. Most accounts that I know of awere either written by German-Texan boosters or were written almost fifty years later, when relations with Native Americans were profoundly different, and the rhetoric of removal had changed. That being said, Meusebach likely mused about the possibilities of Comanche and German co-existence. In this he was not alone. In 1847, there were still people throughout the nation who believed that Native Americans and Europeans could and would live side by side.

Huenlich is also correct to point out that Germans in Texas in 1847 did not see themselves as “Anglo-European.” Too often we think of Texas as Anglo, rather than as the diverse polity it was during the Mexican-American War. What is so interesting about this treaty, and what drew me to it in the first place, was precisely the ways in which it exists outside typical Anglo-Comanche relations. The presence of Americans, Mexicans, Germans, Comanche, and Delaware makes for a fascinating mixture of people, cultures, and political goals. As a result, when looking at this treaty, we must try and imagine an immensely complex world, in which the two of the three biggest political and military actors were at war, and the German-Texans were trying to protect their future access to certain lands.

In this context, Meusebach could only work within prevailing geopolitical systems. On one side were the Comanche, who were undoubtedly feared by both Native Americans and Europeans in the region. On the other, were the U.S. Government and the German Emigration Company, who despite conflicts with each other, agreed on what determined legal ownership of land. The German Emigration Company, which Muesebach represented, had been given a grant of land from the former Republic of Texas, which if they failed to settle, they would lose. As a result, despite the language in the treaty, Meusebach must have been aware that settling the land would, in the eyes of western law, guarantee German-Texan access to it in the future. He would also have been aware, that by German and Anglo reasoning, the company already had rights to own land that was already promised by the U.S. Government to the Comanche.

When we take a step back, and think about Comanche motivation for signing this treaty, two things become apparent. One is the fact that the Comanche saw a very different future for themselves in Texas than the German-Texans saw. The other is that there were existing presumptive rights to land already at work by the time Meusebach entered treaty negotiations. Meusebach was not concerned with money, per se, but he was deeply concerned with property rights, and those property rights were to land that another nation already owned.

Even as Meusebach imagined a future in which the Comanche and Germans lived at peace together, that very desire denied a future in which the Comanche continued to be in control of Comanche land. In order to write a story that does not repeat the removal of people from their land by removing them from history, we must take as our first premise that Europeans, Anglos, German, Spanish, French, etc., had zero right to Indigenous lands. Once we do this, it becomes impossible to see either the Comanche or the Germans as simply friendly and well meaning, and as a result allows us to see how, in 1847, each group imagined radically different futures for themselves and each other than the future that came to pass.

The Comanche imagined a future in which their horse herds still roamed the plains and buffalo still prospered in the American West, in which trade fairs in the center of Comancheria were still economic and cultural centers, and the Comanche military was still feared the way the U.S. military is feared today. It is only once we acknowledge that this was a possibility, and that even well-meaning settlers aspired to lands that were never theirs, that we can begin to understand the violence that settler societies unleashed on North America.

The history I offered in my first article aspired to such an imagination. It is based on this premise that I proposed that the treaty’s significance was greater than its value to German-Texas. The treaty does not point to an alternative future because some German-Texans chose friendship over violence, it points to an alternative future because it gives us insight into myriad possibilities that the Comanche imagined for themselves.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

On November 11, 1918, the guns fell silent in Europe as the armistice with Germany ended World War One. World War I changed the face of Europe and the Middle East. The war had brought bloodshed on an unprecedented scale: tens of millions of people were dead, and millions more displaced. The German and Russian economy were in ruins, and both nations rebuilt in different ways before meeting on the battlefield again a generation later.

All content © 2010-present NOT EVEN PAST and the authors, unless otherwise noted

Sign up to receive our MONTHLY NEWSLETTER