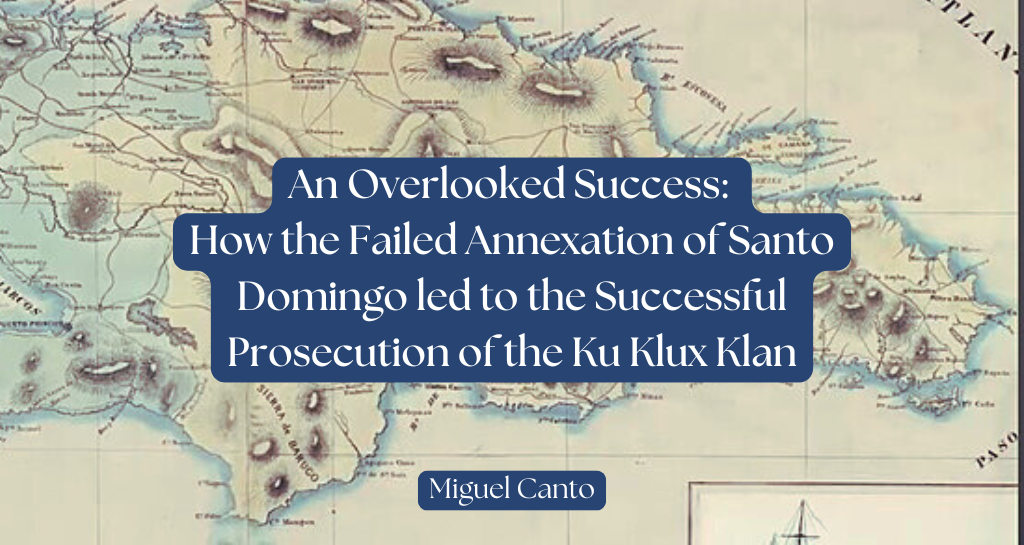

The 19th century in American history is marked by rapid territorial expansion, from the Louisiana Purchase to the Mexican-American War. By 1850, the continental U.S. had taken a familiar shape. The Civil War interrupted this expansion as the nation grappled with the future of slavery and the role of the federal government. However, at the close of the war, during Reconstruction (1865-1877), territorial expansion resumed with the purchase of Alaska and the failed annexation of Santo Domingo, modern-day Dominican Republic. Yet, this attempt at expansion stands out from other additions to U.S. territory. The Annexation was not merely a land grab but a Reconstruction project, recognized as such by both its supporters and its detractors. It yielded no territorial gains, but surprisingly, it was this political fight over Santo Domingo that helped achieve one of Reconstruction’s great successes: the Prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan—America’s first organized terrorist threat.

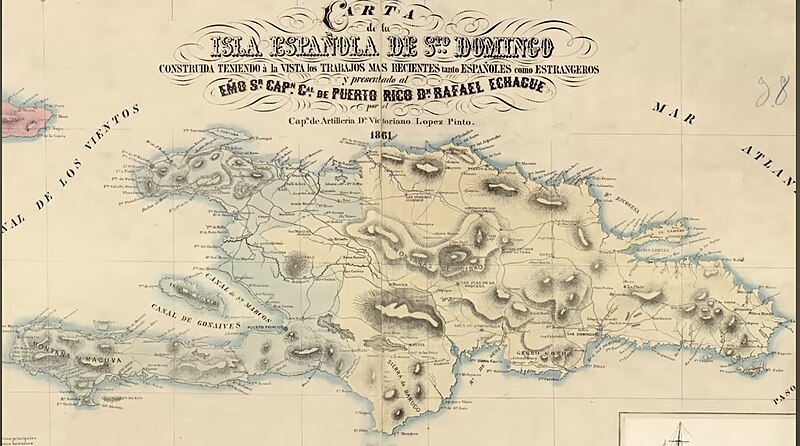

On the first of July 1870, The Baltimore Sun reported that “The treaty for the annexation of the island of San Domingo to the United States was rejected by the Senate this afternoon by a vote of 28 to 28, being ten less than the required two-thirds to secure its ratification.”[1] The tie vote also saw thirteen abstentions, effectively killing what had become a pet project of President Ulysses S. Grant, though the initiative did not start with him. In 1867, Grant’s predecessor, President Johnson, intervened with the government of the recently independent Santo Domingo to aid in its defense against raids from Haiti. In his fourth annual message to Congress in 1868, Johnson detailed the support provided to Santo Domingo and expressed the desirability of acquiring land suitable for a naval base. He also proposed the idea of annexing both republics on the island of Hispaniola: Santo Domingo and Haiti.[2] However, Congress seemed uninterested in this suggestion, mainly because it had already allocated 7.2 million dollars to purchase Alaska in the spring of 1867, under the Johnson Administration.[3]

A High Price to Pay

During the Civil War, Russia was the only major European power to support the Union. Secretary of State William Seward[4] framed the purchase of Alaska as a gesture of goodwill towards the Czar, who was contending with his own conflict in Crimea.[5] Moreover, Congress appeared reluctant to purchase more land, particularly after the establishment of the Joint Special Committee on Retrenchment in 1866, aimed at cutting government spending.[6] The Civil War had cost nearly $5.2 billion, leaving a remaining debt of $3 billion (unadjusted for inflation). To put it into perspective, the annual budget of the government at the start of the war was $63.1 million. This financial reality made it clear in Washington that cost-cutting measures were necessary.[7] Additionally, President Johnson began losing allies in Congress that had helped him with the Alaska deal since he had tried to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, resulting in Johnson’s impeachment in February of 1868.[8] While Congress would not find Johnson guilty nor remove him from office, the American people effectively did so by electing Ulysses S. Grant in November 1868.

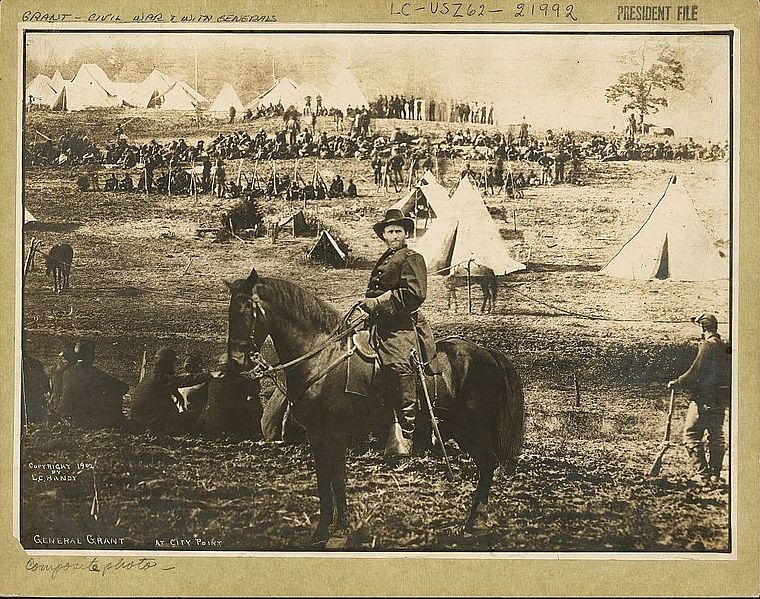

In his relatively short first inaugural address, President Grant spoke of bolstering law enforcement in the South as new terror threats arose, touched on a foreign policy of mutual respect, promised to see the 15th Amendment ratified, and pledged to pursue respectful policies regarding the Native Americans. As important as these subjects were, Grant spent most of his inaugural address talking about debt[9]: “A great debt has been contracted in securing to us and our posterity the Union. The payment of this, principal and interest, as well as the return to a specie basis as soon as it can be accomplished without material detriment to the debtor class or to the country at large, must be provided for.” [10] In over two paragraphs, he laid down a clear mandate to cut spending and pay off the debt.

Indeed, Grant would succeed in this reconstruction project by 1870, having reduced the public debt to $3.1 billion.[11] For Grant and many other radical Republicans, paying off the debt was a part of Reconstruction. However, this prioritization of debt reduction would undermine Congressional support for other Reconstruction projects like the Freedman’s Bureau and the proposed annexation of Santo Domingo. Opposition to the purchase was often linked to its financial cost, as well as broader tensions surrounding the abolition of slavery and the challenges of Reconstruction. While prejudice against the Dominican people was a factor for some, the resistance seemed more rooted in larger national debates of the era than in targeted animosity toward Santo Domingo. Democrat Representative Fernando Wood would say in debating against the treaty, “I am opposed to the San Domingo annexation, not only because of a large sum of money at this time, but also it is another step in the demoralization of the American People”[12]. In this case, “demoralization” refers to the effects of Grant’s Reconstruction.

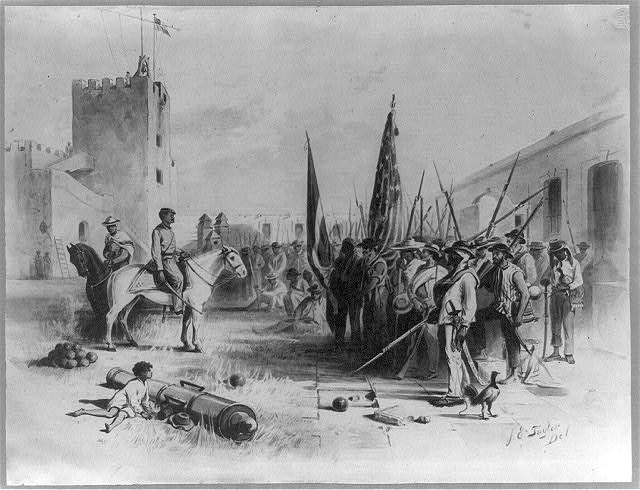

In a letter to President Baez from President Grant on July 13, 1869. This tells us Buenaventura Baez reached out to Grant sometime between January and July 1869. Whatever Baez’s emissary said to Grant piqued his curiosity enough to greet him as a “Great and Good Friend. In the letter, Grant tells Baez that he would be sending Brevet Brigadier General Orville E. Babcock[13] as a special agent to assess the viability of annexing Santo Domingo.[14] Babcock went on to make two trips to the island and serve as the President’s chief emissary in the annexation negotiations. Once there, Babcock quickly realized the extent of Santo Domingo’s disputes with its neighbor, Haiti, with whom it shared the island of Hispaniola. Although Haiti was the smaller country on the island, it had a larger population compared with the sparsely populated Santo Domingo.[15] After gaining independence from Spain in 1821, Haiti invaded Santo Domingo within weeks, leading to a period of occupation. Despite its disadvantage in manpower, Santo Domingo prevailed in the face of a Haitian occupation until 1844.[16] Following its independence, Haitian raids along the borders became a regular occurrence. During this period of rising Dominican nationalism, caudillos (military strongmen or dictators) like Buenaventura Baez seized the moment to gain power, often for personal enrichment. Baez increased military spending to ward off Hattian raids, but this led to a mounting national debt, which reached $1.3 million by 1859[17]. As a result, Baez began seeking protectorate assistance from foreign powers, including the United States.[18]. In his diaries from his second trip to the Island, Babcock notes, “He (Baez) seemed in good spirit, much in favor of annex.”[19] Indeed, there seemed to be widespread support within Santo Domingo.

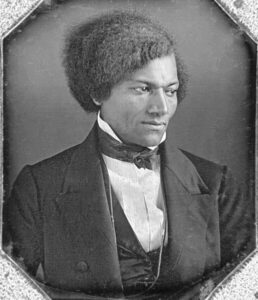

The Role of Fredrick Douglass

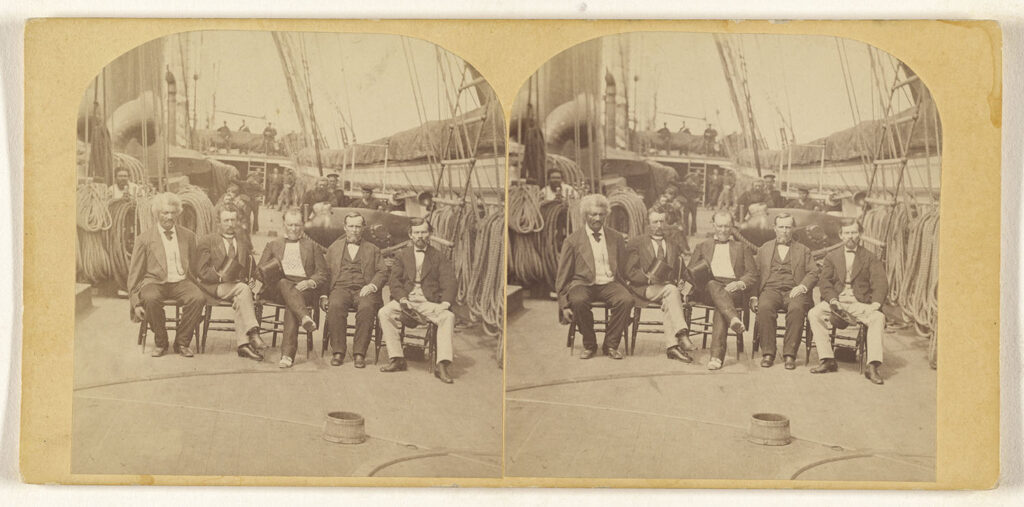

When Babcock returned to Grant, having confirmed that Baez was interested in Santo Domingo being annexed, Grant began using his influence to promote the idea. When word had reached Charles Sumner, he asserted that the people of Santo Doming were opposed to such an arrangement. In response, Grant enlisted Fredrick Douglass to travel to the island in 1871 and determine whether the citizens would support such a move. Douglass had long advocated for normalizing relations with black republics such as Haiti and Santo Domingo.[20] In 1873 he was happy to report that “they want to join their country to the United States and to become citizens of the United States.”[21] While Douglass’ report was based on anecdotal evidence from his conversations with the island’s inhabitants, there had also been a referendum ordered by President Baez with an admittedly low turnout. Still, of the 15,169 votes cast, only 11 were cast against annexation.[22] Despite this turnout, people like Douglas and Grant pointed to this result to demonstrate a political will on the part of the Dominican people to join the US.

Frederick Douglass was not simply advocating for territorial expansion. He viewed the annexation of the island as an opportunity to challenge prevailing prejudices and demonstrate the potential for all people, regardless of race. In his lecture on the annexation of Santo Domingo, Douglas compared the Spanish and French attempts to reenslave the black and mulatto inhabitants to the actions of the Klan in the South, who, after being paroled at Appomattox now formed a terrorist group to strengthen white supremacy. In his own words: “The fact is significant and has a lesson for those men in our county who are still endeavoring by violence and midnight crimes to worry the American negro back into slavery. The negro is no less a man here than in Santo Domingo.”[23] Thus, for Douglass, the annexation of Santo Domingo was closely associated with Reconstruction and civil rights, providing African Americans in the South with an example of resistance to white supremacy. Grant, like Douglas, linked the proposed annexation to the widespread terror of the Ku Klux Klan across the South.

Annexation as Part of Reconstruction

Grant’s first term was marked by intractable domestic issues, from the fight for the Fifteenth Amendment to the war he waged against the Ku Klux Klan in the South. Thus, he turned to foreign policy for what he thought would be an easy victory via the annexation of Santo Domingo. When he argued for annexation, he cited all the usual reasons for the acquisition, such as fertile soil and tropical produce, and strategic interests, such as having a naval base in the Caribbean to bolster the Monroe Doctrine, all common arguments made by the initiative’s supporters in Congress. But Grant went even further. In a memorandum issued to the State Department describing the benefits of the proposed annexation, Grant writes:

Caste has no foothold in San Domingo. It is capable of supporting the entire colored population of the United States, should it choose to emigrate. The present difficulty in bringing all parts of the United States to a happy unity and love of country grows out of the color prejudice. The prejudice is a senseless one, but it exists. The colored man cannot be spared until his place is supplied, but with a refuge like San Domingo, his worth here would soon be discovered, and he would soon receive such recognition as to induce him to stay.[24]

The quote above shows that the annexation of Santo Domingo was wrapped up in Grant’s vision for Reconstruction. This excerpt shows that Grant wanted to keep Black communities in the US while also providing them with a refuge from Ku Klux violence. By the time of this writing, the emigration movement had gained considerable traction, even among the freedmen’s community. With the advent of Klan terror in the South, many Black communities sought refuge in places like Haiti and Liberia. Elias Hill, a notable leader of a Black church from South Carolina—where Klan activity had been incredibly violent—led the whole of his congregation in a move to Liberia.[25] However, offering a place to flee wasn’t the only way Grant linked Santo Domingo to Reconstruction. He also saw the annexation of Santo Domingo as a way of ending slavery in other parts of the hemisphere. In a speech after the treaty was rejected, Grant urged Congress to reconsider, arguing that an American government on the island would prompt enslaved people in the Caribbean to flee to Santo Domingo as a refuge. He further asserted that “Porto Rico and Cuba will have to abolish slavery as a measure of self-preservation to retain their laborers.”[26]

Grant wasn’t the only one that connected Santo Domingo to the Reconstruction, those opposed the annexation also made this link. In 1870, many of the arguments used by Democrats against the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment were echoed in their opposition to annexing Santo Domingo. Representative Fernando Wood, for instance, recycled his arguments against the Fifteenth Amendment in a Congressional debate stating, “As wicked as is the attempt to compel the fusion of two such opposite races existing among ourselves, it would be far more suicidal and criminal to add the people of San Domingo also.”[27] Importantly, when Wood referred to the “fusion of two opposite races,” he was speaking of the impact of the amendment on the communities of freed blacks born in the United States, as it granted them citizenship. Indeed, the democrats’ opposition to the proposed annexation reflected their broader resistance to naturalizing freed Blacks.

Predictably, Democrats opposed the annexation of a Latin American republic with a significant Black and mixed-race population. Still, those sentiments were shared by less radical Republicans like Senator Justin S. Morrill, who allied with Charles Sumner in his opposition to the treaty. In an 1871 speech, Morill spoke of the formerly enslaved Americans who had recently been made citizens by the 15th Amendment, saying, “It is useless to disguise the fact that the people of a portion of our present territory have not become assimilated with the American people and American Institutions, and the time when they will do so must be computed, not in years, but by generations.”[28] Even critics of the acquisition recognized the connection between the proposed annexation and Reconstruction. Sentiments like those expressed by Morrill and Sumner led to fissures in the Republican party, leaving President Grant feeling betrayed.

A Misunderstanding with Mr. Sumner

Ultimately, it was Charles Sumner’s refusal, as Chair of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, which prevented the treaty from being passed. While he had supported the annexation of Alaska just a few years earlier, he refused to admit Santo Domingo. Sumner, along with Thadeus Stevens, had led the radical wing of the Republican party, but the two began to diverge when it came to handling Reconstruction. The more radical Stevens thought the South should be treated as conquered territory, while Sumner sought a conditioned reconciliation with the South.[29] Due to his leadership among the Radicals and his well-established support for Reconstruction, Grant expected Sumner’s support. Before moves had been made in Congress, Grant shared an early draft of the treaty with Sumner, to which Sumner promised his “friendly consideration.” Grant, still relatively new to politics, interpreted this as support for the acquisition.[30] This misunderstanding undermined Grant’s efforts to secure the treaty and led to him to push for a vote in the Senate without the necessary support from his party.

Sumner had his reasons for not supporting the treaty, some of which, as noted above, were rooted on pseudoscientific ideas of geographic racial determination.[31] But Sumner also sympathized with the Dominican nationalist arguments and distrusted Baez, whom he viewed as a despot trying to sell off his country. “A convention was appointed, not elected, which proceeded to nominate Baez for the term of four years, not as President, but as Dictator. Declining the latter title, the triumphant conspirator accepted that of Garn Ciudadano or Grand Citizen with unlimited powers…Naturally, such a man would sell his own country.” [32] Siding with the Dominican Nationalists, Sumner thought that support for the treaty represented a betrayal of its inhabitants by Baez, who he characterized as a villain.

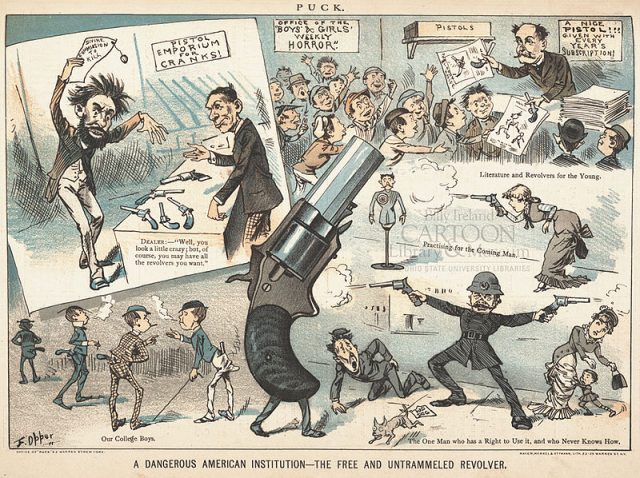

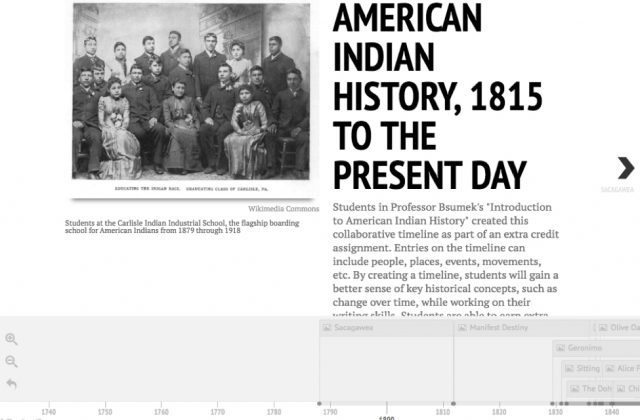

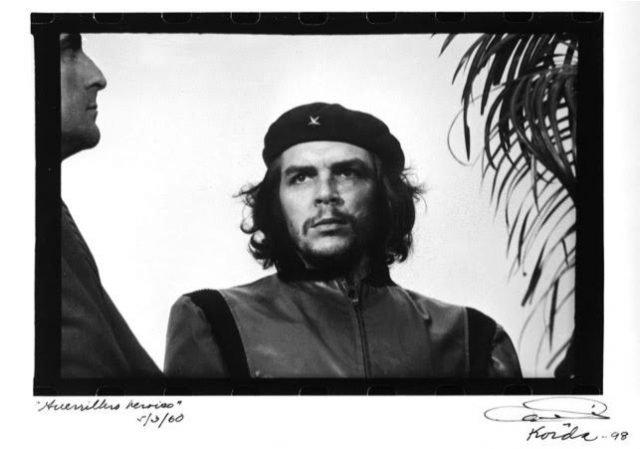

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A correspondent of Sumner’s, General Gregorio Luperón, a leader in the Dominican Nationalist movement, wrote to Grant in late 1869 expressing his anger with the U.S. Navy in the sinking of the Telegraph, a ship used to transport Dominican Nationalists from Haiti to Cuba. President Johnson sank the ship as part of his established protectorate, but now he directed his anger squarely at Grant. The General wrote, “Spain, in spite of its traditional quixotism, rejected the cowardly Baez’s undignified petition, and to our understanding, the Spanish Government’s course of action was more honorable than yours…Your Excellency had the weakness to order, to authorize the destruction of Telegraph, accepting the immoral decree of Baez’s mercenary Senate.”[33] Issuing the protectorate and the actions of the U.S. Navy were primary reasons for Sumner’s opposition, and would cite incidents like the sinking of the Telegraph in his arguments against the annexation: “It is difficult to see how we can condemn with proper, whole-hearted reprobation, our own domestic Ku Klux with its fearful outrages while the President puts himself at the head of a powerful and costly proceeding operating abroad in defiance of International Law and the Constitution of the United States.”[34] For Sumner, Grant’s actions, which he viewed as violations of the Constitution and an “usurpation of war powers,” undermined the moral authority Grant had built through his prosecutions of the Klan.

The Santo Domingo Purge

In the fight for the annexation treaty, many in Grant’s cabinet saw that Santo Domingo was a losing battle long before Grant. Grant pressed on, ordering his department heads to spend political capital to have the treaty passed. Despite these efforts, support for the treaty was never strong. After many in his cabinet had sided with Charles Sumner, whose support was crucial, Grant began to rail against his disloyal cabinet. According to a diary entry by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, Grant claimed that “the Secretary of the Interior is opposed to it; the Attorney-General says nothing in its favor, but sneers at it; and the Secretary of Treasury does not open his mouth.”[35] Indeed, Grant’s break with Sumner and less radical Republicans led to a purge within his cabinet, and he began dismissing all those members of his administration who served Sumner. While this may initially appear vindictive, there was some positive outcomes. Attorney General Ebenezer Hoar, a long-time friend of Charles Sumner who had opposed the treaty, Was initially recommended for the position of AG by Sumner. On July 15, 1870, Hoar received a letter requesting his resignation.[36] A month earlier, Grant submitted a new name for Attorney General, a man named Amos T. Akerman.[37]

But Akerman’s work as head of the new Department of Justice has largely been a footnote to history. Akerman, a former Confederate officer who has become a staunch Republican, had been personally threatened by the Klan for his shift in allegiance. He would go on to aggressively prosecute the Klan, effectively dismantling the organization for nearly four decades.[38] His appointment seems providential, considering the Act to Establish the Department of Justice does not mention civil rights.[39] Furthermore, it was the Joint Select Committee on Retrenchment and not a judiciary committee that passed it. This represented a move toward civil service reform and a cost-saving measure.[40] Indeed, Akerman ran up against repeated funding shortages throughout the Klan trials. However, Akerman oversaw the prosecutions heavily and even directly called on Grant to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in several counties in South Carolina. While coincidental, the proposed annexation of Santo Domingo led directly to one of the most successful reconstruction projects, the prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan.[41] What appeared to be a typical territorial land grab was, in fact, closely connected to the broader goals of the Reconstruction.

Conclusion

In the end, the proposed annexation of Santo Domingo failed, defeated by a strange alliance between well-meaning radical Republicans and racist Democrats, killing Grant pet project and limiting his vision for Reconstruction. Yet, the political fight over Santo Domingo played a pivotal role in staffing the newly founded Department of Justice with a leader who possessed the will to Prosecute the Ku Klux Klan. Unlike other territorial expansions, this attempt was directly linked to the question of Reconstruction, and not only by President Grant and his supporters, but also by those opposed to the treaty. Regardless of the failure to secure the annexation, it is clear that the debate surrounding this Reconstruction initiative contributed to one of the era’s greatest successes.

Acknowledgements:

This article originates in Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s capstone undergraduate seminar.

Miguel Angel Canto Jr. is a first-generation college student and hopeful law school applicant, expected to graduate this May with a Bachelor’s in History and Philosophy. He is working on his undergraduate honors thesis on the establishment of the U.S. Department of Justice. His research interests include the legal history, history of ideas, history of republics and American history, particularly Reconstruction and the Gilded Age.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] “The San Domingo Treaty Rejected,” The Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1870, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-baltimore-sun-the-san-domingo-treaty/158127723/.

[2] “December 8, 1868: Fourth Annual Message to Congress | Miller Center,” October 20, 2016, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/december-8-1868-fourth-annual-message-congress.

[3] United States and Russia, eds., Treaty Concerning the Cession of the Russian Possessions in North America by His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias to the United States of America (Washington, 1867), https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.treatyconcerning00unit/.

[4] Secretary of State for President Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

[5] “The Alaska Purchase, Articles and Essays, Meeting of Frontiers, Digital Collections,” web page, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/collections/meeting-of-frontiers/articles-and-essays/alaska/the-alaska-purchase/.

[6] The 39th Congress, “Concurrent Resolution Providing for a Joint Select Committee on Retrenchment” (Congressional Globe, 1866).

[7] “History of the Debt,” TreasuryDirect, accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.treasurydirect.gov/government/historical-debt-outstanding/.

[8] “The Impeachment Trial of President Andrew Johnson | Century Presentations | Articles and Essays | A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates 1774-1875 | Digital Collections | Library of Congress,” web page, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/collections/century-of-lawmaking/articles-and-essays/century-presentations/impeachment/.

[9] Grant Ulysses, “First Inaugural Addresses of Ulysses S. Grant,” Text, Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States (Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.: for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 1989, March 4, 1869), https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/grant1.asp.

[10] First Inaugural Addresses, Grant, 1869.

[11] “Public Debt of the United States. 1870, 1880, 1890 and 1902. [Washington, D. C. 1903].,” online text, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed December 4, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.2080020a/?st=gallery.

[12] United States Congress, “The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Second Session Forty-First Congress; Together with an Appendix, Embracing the Laws Passed at That Session, (1870): 3034-3038.,” Book, UNT Digital Library (John C. Rives, 1870), United States, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc30886/m1/209/.

[13] Babcock had served as one of Grant’s aides-de-camp during the Civil War.

[14] “Letter to President Buenaventura Baez of the Dominican Republic | The American Presidency Project,” accessed November 6, 2024, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/letter-president-buenaventura-baez-the-dominican-republic.

[15] John B. Crume, President Grant and His Santo Domingo Project: A Study of Ill Judgement (Florida Atlantic University, 1972) p. 11.

[16] “History of the Dominican Republic, Government, Facts, President, & Flag, Britannica,” October 28, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Dominican-Republic.

[17] Commission of Inquiry to Santo Domingo, “Report of the Commission of Inquiry to Santo Domingo” 1 (1871): I–II, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.cow/reciqsadm0001&i=1, p. 178.

[18] Luis Martínez-Fernández, “Caudillos, Annexationism, and the Rivalry between Empires in the Dominican Republic, 1844–1874,” Diplomatic History 17, no. 4 (1993): 571–97, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24912228.

[19] Orville E. Babcock, “Orville E. Babcock Diary: The Second Journey to Santo Domingo November 8th to December 2nd, 1869” (Mississippi State University, 1869).

[20] Merline Pitre, “Frederick Douglass and the Annexation of Santo Domingo,” The Journal of Negro History 62, no. 4 (October 1977): 390–400, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/stable/2717114.

[21] Frederick Douglass, “Frederick Douglass Papers: Speech, Article, and Book File, 1846-1894; Speeches and Articles by Douglass, 1846-1894; Undated; ‘Santo Domingo,’ Manuscripts, Typescripts, and Fragments; 1 of 5” (1873), mss11879, box 28; reel 18, Manuscript Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss11879.28013/.

[22] Harold T. Pinkett, “Efforts to Annex Santo Domingo to the United States, 1866-1871,” The Journal of Negro History 26, no. 1 (January 1941): 12–45, https://doi.org/10.2307/2715048.

[23] Douglass, “Frederick Douglass Papers.”

[24] Ulysses S. Grant, “Memorandum,” The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, November 1,1869-October 31, 1870, edit. John Simon, vol. 20 (Mississippi State University, 1995), https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/20, p. 74.

[25] Scott Farris, Freedom on Trial: The First Post-Civil War Battle over Civil Rights and Voter Suppression (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2020,) p. 59.

[26] Ulysses S. Grant, “Making the Case for US Annexation,” in The Dominican Republic Reader : History, Culture, Politics, ed. Eric P. Roorda and et al. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, n.d.), 158–60, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utxa/detail.action?docID=1689436.

[27] United States Congress, “The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Second Session Forty-First Congress; Together with an Appendix, Embracing the Laws Passed at That Session, (1870): 3034-3038.,” Book, UNT Digital Library (John C. Rives, 1870), United States, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc30886/m1/209/, p. 1187.

[28] Justin S. Morrill, “Opposition to US Annexation,” in The Dominican Republic Reader: History, Culture, Politics, ed. Eric P. Roorda, et al. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014), https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utxa/detail.action?docID=1689436.

[29] Fergus M. Bordewich, Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction, First United States edition (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023,) p. 14-15.

[30] Chernow, Grant, p. 691-692.

[31] Hidalgo, “Charles Sumner and the Annexation of the Dominican Republic.”

[32] Charles Sumner, “Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts on the St. Domingo Resolutions; Delivered in the Senate of the United States,” March 27, 1871, HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112102553197&seq=3&q1=santo+domingo.

[33] Gregorio Luperón, “Dominican Nationalism versus Annexation,” in The Dominican Republic Reader : History, Culture, Politics, ed. Eric P. Roorda and et al. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014), 171–72, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utxa/reader.action?docID=1689436&ppg=188.

[34] Sumner, “Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts on the St. Domingo Resolutions; Delivered in the Senate of the United States.”

[35] Chernow, Grant, p. 698.

[36] Ulysses S. Grant, From Grant to Hoar, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, November 1,1869-October 31, 1870, ed. John Simon, vol. 20 (Mississippi State University, 1995), https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/20, p. 170.

[37] Ulysses S. Grant, Appointment of Amos T. Akerman The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, November 1,1869-October 31, 1870, ed. John Simon, vol. 20 (Mississippi State University, 1995), https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/20.

[38] Farris, Freedom on Trial, p. 78.

[39]An Act to Establish the Department of Justice.” P.L. 41-97 Stat.162, 1870 U.S.C. 41st Congress. Justice.gov, 2013. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/jmd/legacy/2013/10/23/act-pl41-97.pdf.

[40]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, “The Creation of the Department of Justice: Professionalization Without Civil Rights or Civil Service,” Stanford Law Review 66, no. 1 (2014): 121–72, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24246730.

[41] Farris, p. 283.