“They killing people everywhere for no reason at all but being black.”

—Cherry (the wife of Nat Turner played by Aja Naomi King)

By Ronald Davis

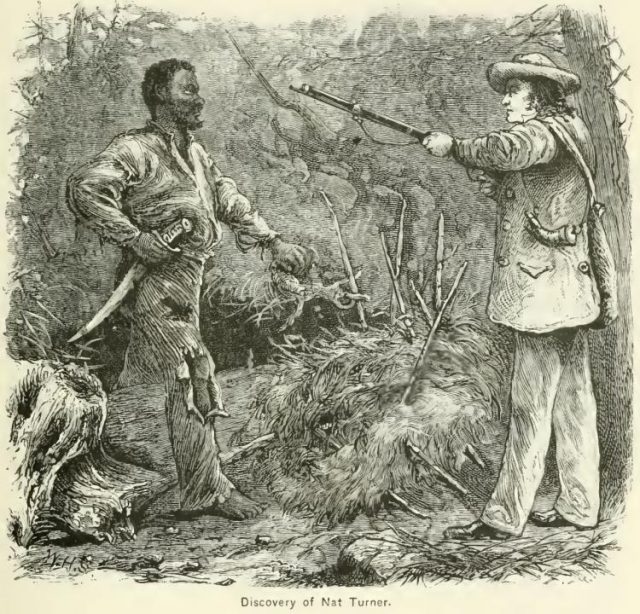

The number of books, novels, articles, plays and movies committed to the life and times of Nat Turner is vast. None of these sources is without controversy. It should be no surprise that Nate Parker’s latest rendition has found its way into the controversy surrounding the life of Nat Turner. Turner and the insurrection he led challenged the perception of the enslaved as passively accepting their enslavement. Early twentieth-century scholars of African-American history often ignored or dismissed the Turner rebellion as an anomaly, as not representative of the institution of slavery in the United States. These writers — U.B. Phillips, Frank Tannebaum, and Stanley Elkins, to name a few — point to the prevalence of revolt in the Caribbean and South America, where large-scale rebellions of the enslaved took place. These scholars deduced that slavery in the United States was mild in comparison to the other slave societies in the Americas because here, in the United States, there were only two or three insurrections of note. Besides the Turner revolt, most early twentieth-century scholars only considered the Denmark Vesey conspiracy and the John Brown slave revolt at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia as evidence of slave discontent and evidence of martial organization. All these revolts, including that of Nat Turner in Southampton, Virginia always stood as a reminder that some enslaved people would kill, bleed, and die to establish freedom.

Nate Parker refashions the memory of Nat Turner, in a sense reclaiming the “fiend,” as described by Thomas R. Gray in The Confessions of Nat Turner, and creating a hero. Parker is not the first (nor I suspect the last) to attempt this revision of Turner. In his 1947 seminal work on enslaved resistance, Herbert Aptheker describes Nat Turner as one of history’s greatest leaders because “he sensed the mood and feelings of the masses of his fellow beings, not only in his immediate environment but generally.” Aptheker’s Nat Turner is an undervalued hero, a man of revolution and liberty: a leader who was able to rouse his compatriots and create in them the desire to fight, and eventually die, for their liberty.

Throughout his life, Nat Turner was the human property of Benjamin Turner, Samuel Turner, Putnam Moore and Joseph Travis. However, in Parker’s film, the audience is presented with only one enslaver, Samuel Turner. Parker portrays Samuel Turner through several different lenses. As children, Nat and Sam are depicted as playmates. Several narratives of the enslaved recount how, in childhood, they played with their enslaver’s children. As Nat and Sam aged, their relationships began to reflect the societal differences between the races. James Curry, a successful runaway from North Carolina, related playing with his enslaver’s children and the feeling of brotherhood between black and white as children. Curry relates that as the children aged they were separated, with white children attending school and black children remaining on the plantation. According to Curry, the children “learn that slaves are not companions for them…the love of power is cultivated in their hearts by their parents, the whip is put into their hands, and they soon regard the negro in no other light than as a slave.” (Slave Testimony 130). After depicting childhood friendship, throughout the remainder of the film, Parker’s Nat Turner wields an almost supernatural influence over Samuel Turner. Parker demonstrates Nat’s psychological influence over Samuel when Nat convinces Samuel to purchase an enslaved woman who eventually became his wife. The depiction of influence continues until Samuel Turner realizes he can commodify not only Nat Turner’s physical labor, but also his mental labor as a preacher to the enslaved.

Armie Hammer as Samuel Turner and Nate Parker as Nat Turner in The Birth of a Nation (Fox Searchlight Pictures via wbur).

Perhaps the most historically accurate portion of The Birth of a Nation is Nate Parker’s depiction of various enslavers. Parker sketches the enslavers as violent, when enslaved men are forced fed during a hunger strike; as paternalistic, in the case of Samuel Turner; and as sexually predatory, when Samuel Turner offers the wife of an enslaved man for intercourse with one of the guests at his party. The different types of enslavers portrayed are not all-encompassing; however, within the limitations of movies and film, Parker made specific choices to expand the American public’s understanding of slavery’s cruelties and daily life.

Given the limitations of filmmaking (budget, time constraints on character exploration, and film length) Parker simplified some aspects of slavery while complicating enslaved masculinity and resistance. At times Parker’s representation of enslaved women simplifies the complexities of womanhood in the Antebellum South, leaving much to be desired. Although his movie is essentially one of raw masculinity, the decision to minimize the intellectual influence of enslaved women does a disservice to the strength of women as agitators, resistors, and participants in the Antebellum South’s peculiar institution. By contrast, some women play a very important role in the film; Nat’s mother, grandmother, and wife are integral to his life. However, Parker makes the decision to limit the viewer’s understanding of enslaved women’s complex humanity. There are moments in the film where it appears that Parker forgets that mothers, wives, and daughters performed the same arduous labor as men.

Aja Naomi King as Cherry (via NCR).

Nat Turner was a father, husband, son, and revolutionary. No one word can describe him except “complex.” Parker, however, makes no attempt to complicate Nat Turner; he wants to create a hero. Parker’s Nat Turner makes this reviewer wonder if slavery is a pretext to depict contemporary African-American masculinity in the film. Parker’s desire is to demonstrate that enslaved men were not passive receptors of slavery but active fighters against an unjust institution. The filmmaker emphasizes one trope of masculinity: to fight until the death for freedom. He inscribes his Nat Turner with this type of masculinity and creates a character full of compassion for the downtrodden and rage at injustice. In one scene, when Nat Turner is helping a young white child, the child’s father notices and begins to hit Turner. Turner does not flinch from the blows but stands tall in the face of injustice. Parker’s Nat Turner begins his insurrection because his wife is raped and beaten beyond recognition (the image of Cherry, Nat Turner’s wife, is reminiscent of the beaten face of deceased Emmett Till). Parker makes the impetus for revolution not the rape of his wife but the power structure that would allow this type of brutality to go unpunished. Although there is no evidence to suggest that this was the historic Nat Turner’s inspiration, it remains plausible that Turner or his co-conspirators fought for the mothers, sisters, and daughters sold or raped by enslavers.

The Nat Turner of historical record is somewhat different than Nate Parker’s representation. Much of what we know of Nat Turner relies on his confession to the attorney Thomas R. Gray (available for free from Project Gutenberg). It is important to interrogate this source, to question Turner’s voice as presented in the text and the motivations of Thomas Gray: was it profit, fame, or a desire for truth that led him to Turner’s prison? As with much of the story of the enslaved, the historical record is woefully incomplete and often clouded in mystery.

Can a movie created for entertainment and education accurately reflect a historical record full of silences? Do the archival silences (i.e. Nat Turner speaking for himself, not as interpreted by another person) of Nat Turner’s life give license to an entertainer; license to create a hero and remove the stain of villainy associated with his memory? Parker does not hesitate to refashion Nat Turner.

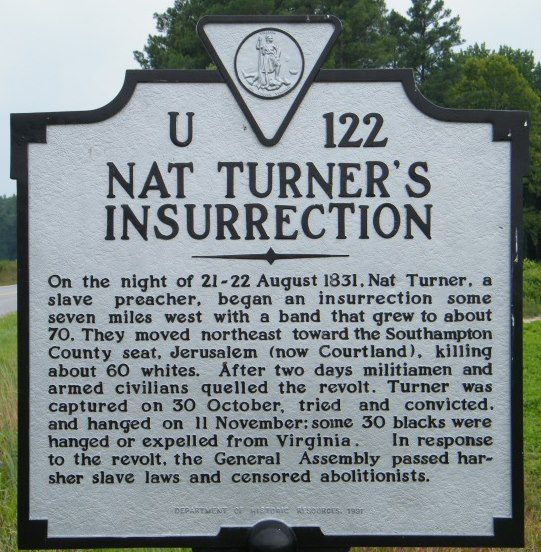

Historical marker in Southhampton, VA (via TheClio).

Scholars can and should take issue with many aspects of The Birth of a Nation’s historicity. The film takes wide liberties with history while portraying underrepresented aspects of slavery accurately. However, as a film it also moves into the realm of popular history and some members of the audience inevitably will absorb the film as a factual representation of nineteenth-century Virginia. This is a problem of the film and filmmaking about historic events in general. However, I would challenge myself and other scholars to view Parker’s movie as an opportunity to further affect the public’s understanding of history. It is an opportunity for historians to have a dialogue with the nation about America’s past and to better explain the complexities of American institutions.

Is Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation historically accurate? No. But what historical drama can lay claim to 100% accuracy? Nate Parker did not set out to make a documentary, nor did he write a history of American slavery. He created a movie at a particular moment in American history. A moment where black lives are confined to prisons at disproportionate rates. A moment when much of the African-American population is frustrated with the callousness of society. The Birth of a Nation is a beginning; it is a chance to continue the conversation about racial inequality. Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation should be seen not for its historic content but for its commentary of this moment in American history.

![]()

Sources:

John W. Blassingame, ed. Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies (1977).

![]()

You may also like:

Daina Ramey Berry and Jermaine Thibodeaux review Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2002).

Mark Sheaves discusses Slavery and its Legacy in the United States.

Not Even Past contributors offer an overview of articles about the history of slavery in the United States.

![]()