Millions of tweets and millions of state documents. Intimate oral histories and international radio addresses. Ancient pottery and yesterday’s memes. Historians have access to this immense store of online material for doing research, but what else can we do with it? In Spring 2018, graduate students in the Public and Digital History Seminar at UT Austin experimented with ways to make interesting archival materials available and useful to the public; to anyone with access to a computer. Over the Summer, Not Even Past will feature each of these individual projects.

Created by Brittany Erwin, “Bureaucracy on the Ground: The Gálvez Visita of 1765” examines the localized consequences and on-the-ground implications of the royal inspection, or visita general, administered by José de Gálvez in New Spain from 1765-1771. The project includes a curated collection of digitized documents from the Genaro García Collection at the Benson Latin American Collection, blogs, and lesson plans.

More on Erwin’s project and The Public Archive here.

Also by Brittany Erwin on Not Even Past:

The Museo Regional de Oriente in San Miguel, El Salvador

The National Museum of Anthropology in in San Salvador

Review of The Archaeology and History of Colonial Mexico by Enrique Rodríguez Alegría (2016)

You may also like:

Renata Keller reviews Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 by J.H. Elliott (2007)

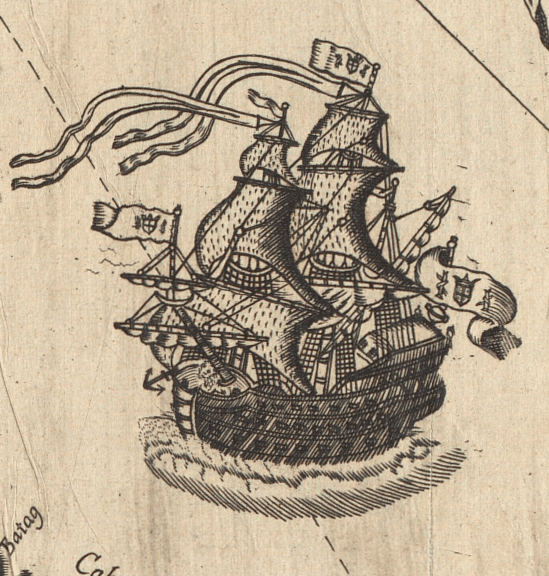

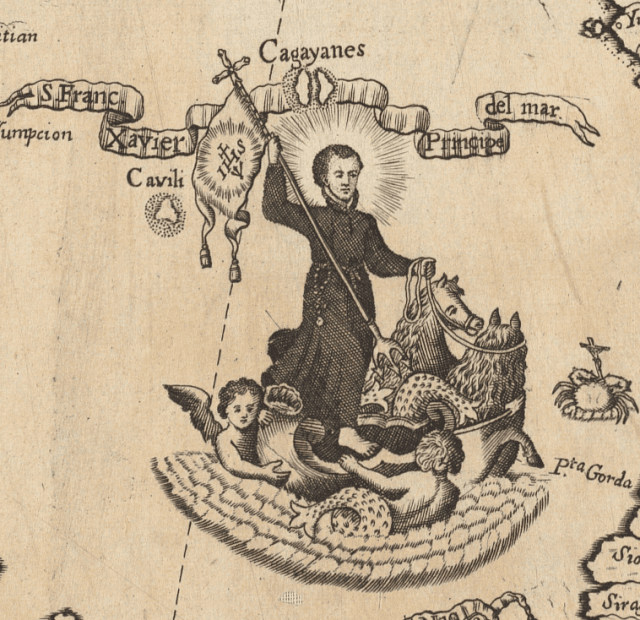

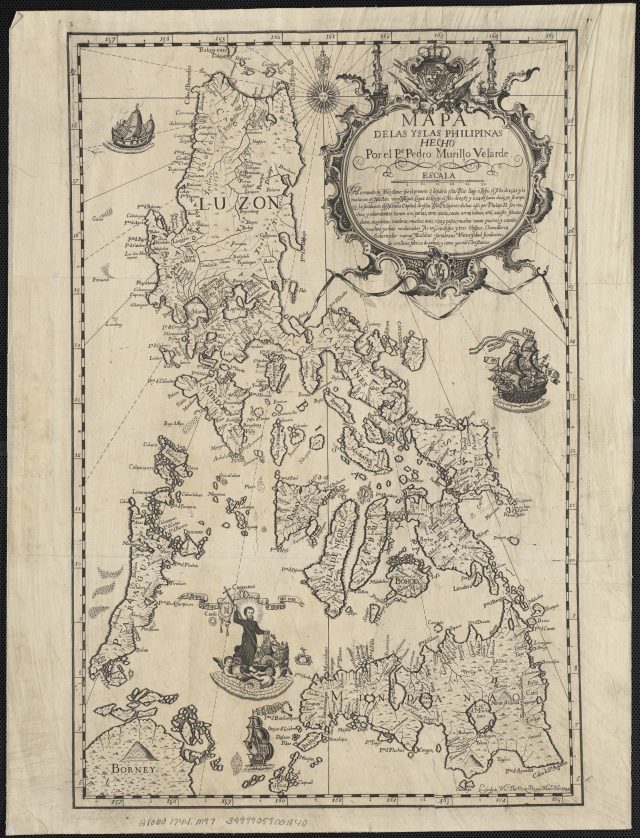

Acapulco-Manila: the Galleon, Asia and Latin America, 1565-1815 by Kristie Flannery

Antonio de Ulloa’s Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional by Haley Schroer