When Brittany Friedman began researching the formation of the Black Guerilla Family, a prison-based organization affiliated with the Black Power Movement, many people questioned the relevance of her project. Friedman recalled one interview with a former California Department of Corrections (CDC) official who, upon learning of her research topic, laughed and asked, “Why would you do that?”[1] From the perspective of state officials, this story had been written decades ago. The CDC and other government agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), had generated thousands of pages of documentation and reports on the Black Guerilla Family and other “Black Extremist” organizations. What more could a new study possibly add?

In fact, the resultant book, Carceral Apartheid, reveals a much more complex story. Friedman, an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Southern California, conducted over forty interviews with the founders of the Black Guerilla Family, CDC officials, and members of other race-based prison organizations such as the Aryan Brotherhood. Friedman describes her approach as historical ethnography. She uses these interviews to “invigorate and triangulate” traditional archival sources including prison administration documents, surveillance records, and personal correspondence.[2] Together, these sources paint a troubling portrait of the conditions that precipitated the creation of the Black Guerilla Family in California’s San Quentin Prison in 1970.

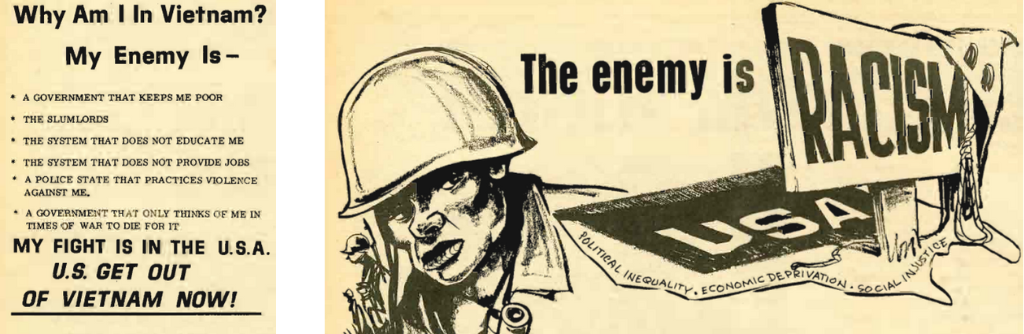

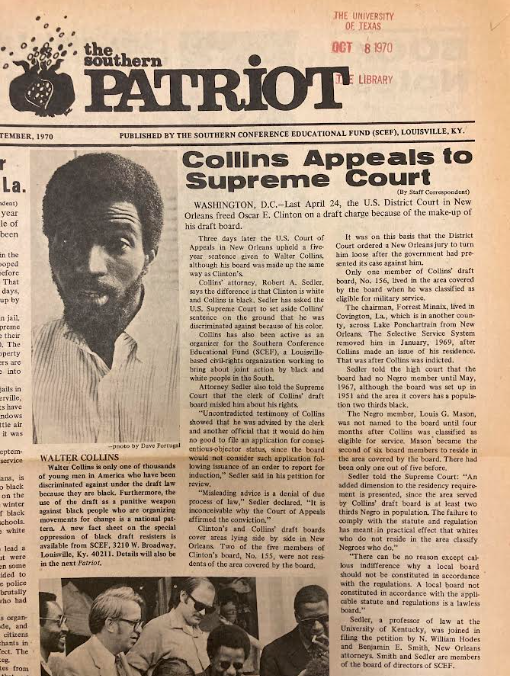

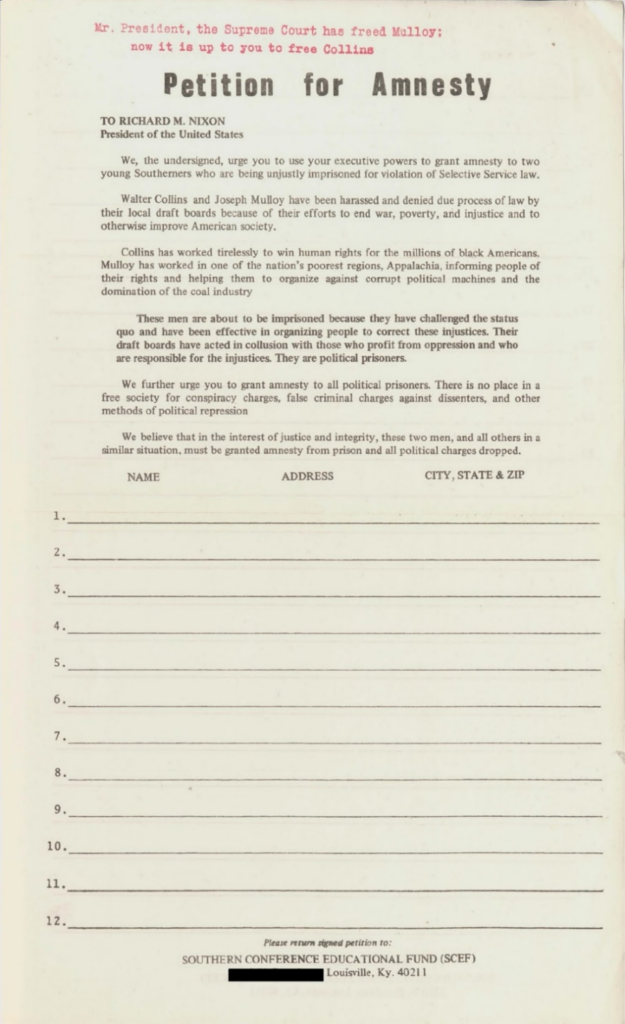

Popular narratives reduce the Black Guerilla Family (BGF) to a prison gang involved in criminal activity and the contraband economy. However, in tracing the group’s origins, Friedman argues that the founding of the BGF was a response to the system of carceral apartheid that structured—and continues to structure—life behind bars in the United States. California prison officials used racial classification systems to create divisions within the prison population and relied on white prisoners, especially those affiliated with white supremacist groups like the Aryan Brotherhood, to maintain the prison’s hierarchy. Officials fostered interracial conflict by spreading rumors, supplying weapons to white prisoners, and failing to intervene when violence broke out. In this way, the CDC was able to maintain a strict system of racial segregation that operated without any formal policy in place. Many of the people Friedman interviewed joined race-based groups such as the Mexican Mafia, Aryan Brotherhood, or the Black Guerilla Family out of fear. Traversing racial lines was often met with violent repercussions. This extralegal violence was not only sanctioned but encouraged by prison officials. As Friedman acknowledges, carceral apartheid relies on this relationship between state-sanctioned legal controls and extralegal violence and intimidation.

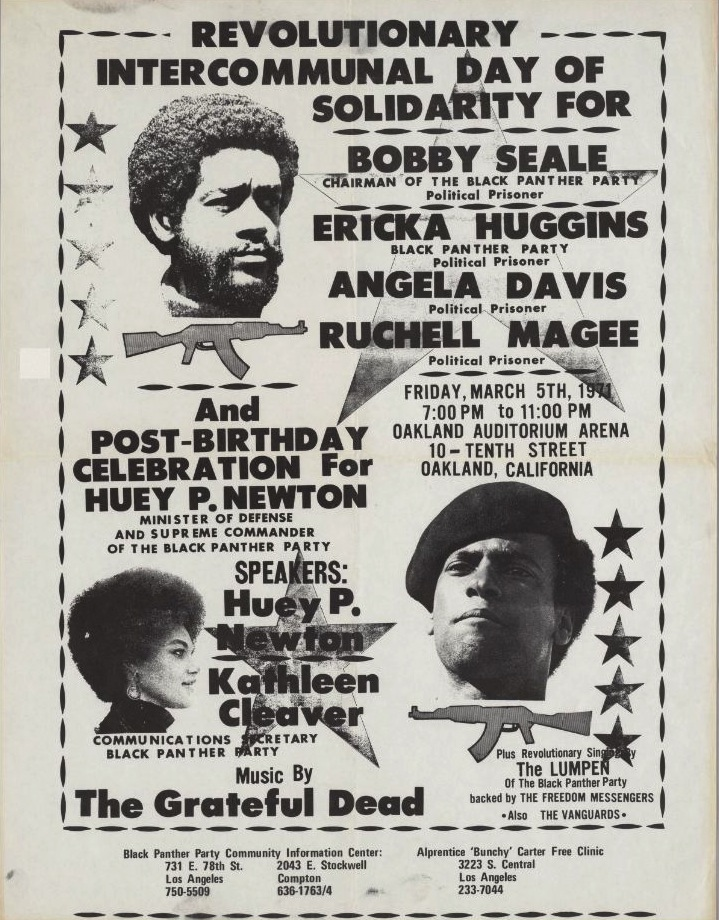

It was within this context that the BGF emerged. Drawing from her extensive interviews with founding members, Friedman argues that this group differed from existing prison gangs in two ways. First, the group was formed defensively to protect Black prisoners from the pervasive violence that they were subjected to by other prisoners and guards. Second, the BGF adopted a political stance that was influenced by organizations including the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Members were expected to engage in political education, develop skills in martial arts and hand-to-hand combat, and take an oath modeled after that of the Kenyan Mau Mau, who challenged British colonial rule through armed rebellion. Over time, the BGF would spread outside of California. In the process, it became less politically oriented and more closely connected to the prison’s illicit economy. As Friedman writes, this was largely due to the increase in membership and the CDC’s crackdown on political activity.

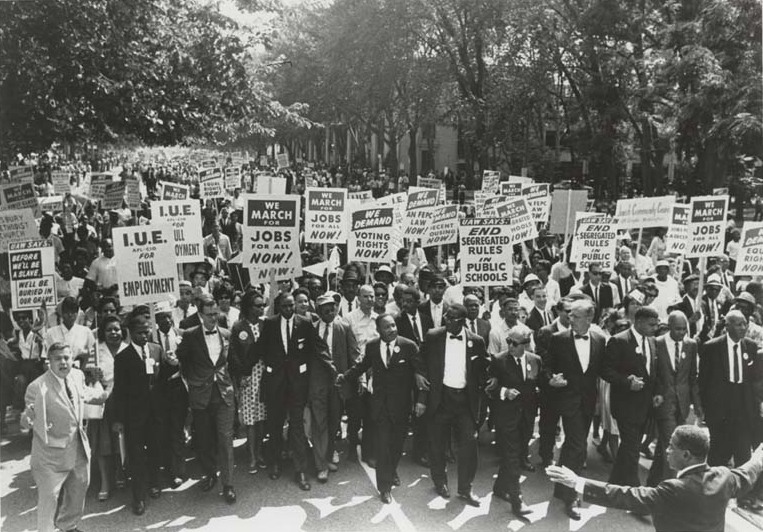

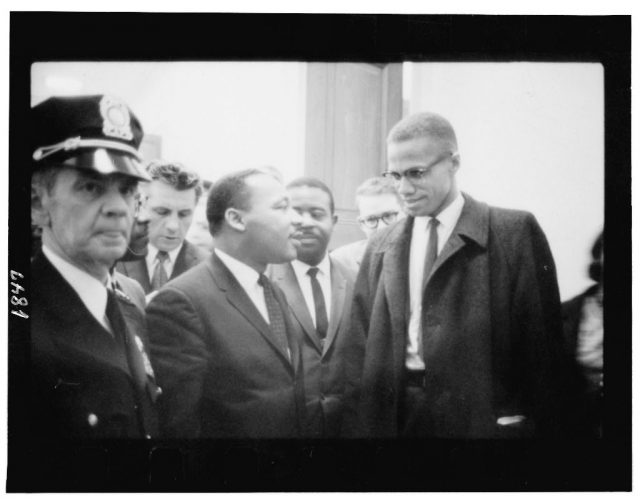

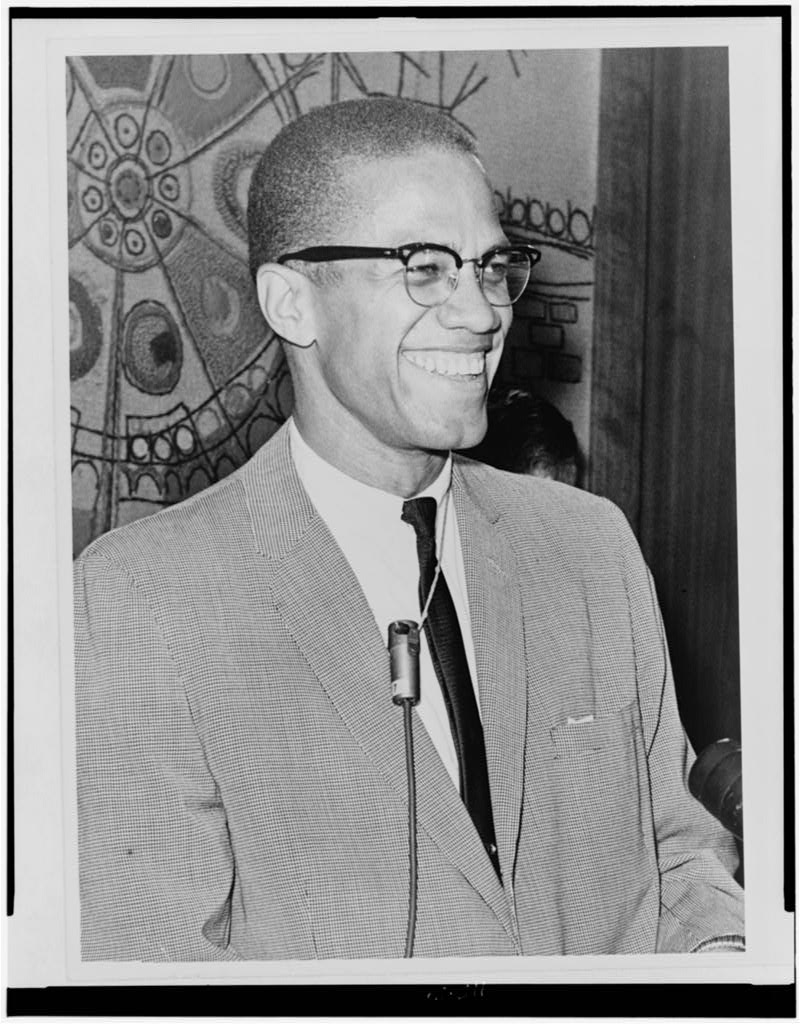

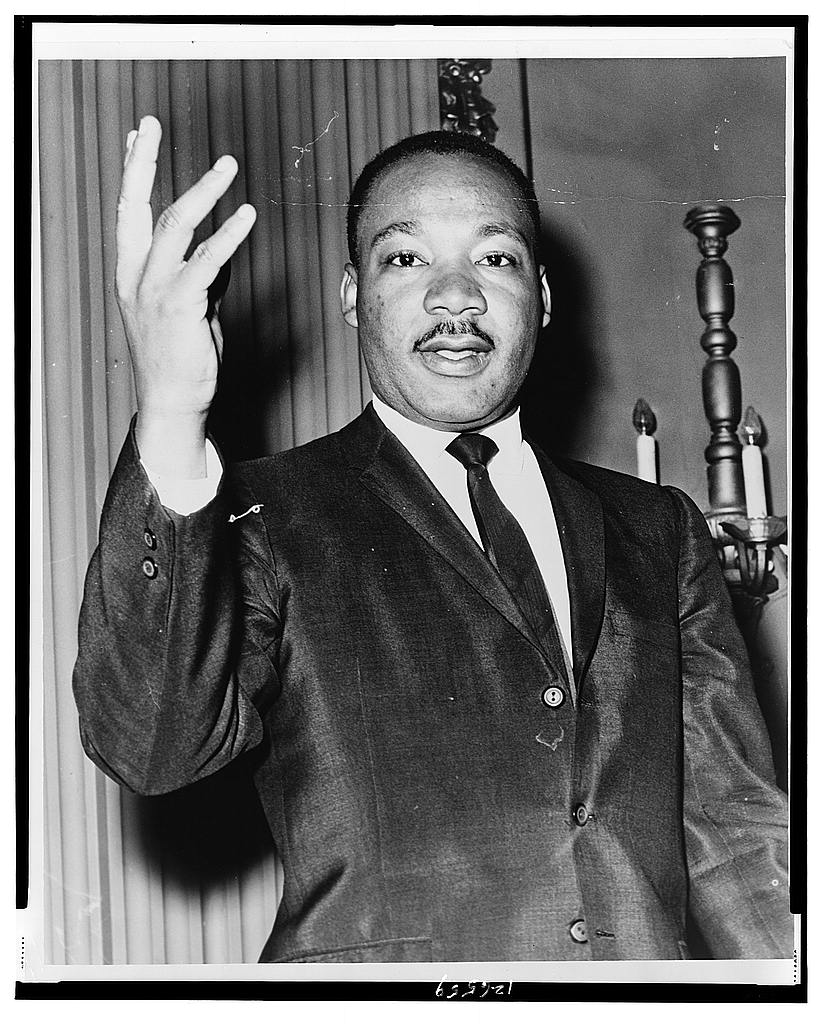

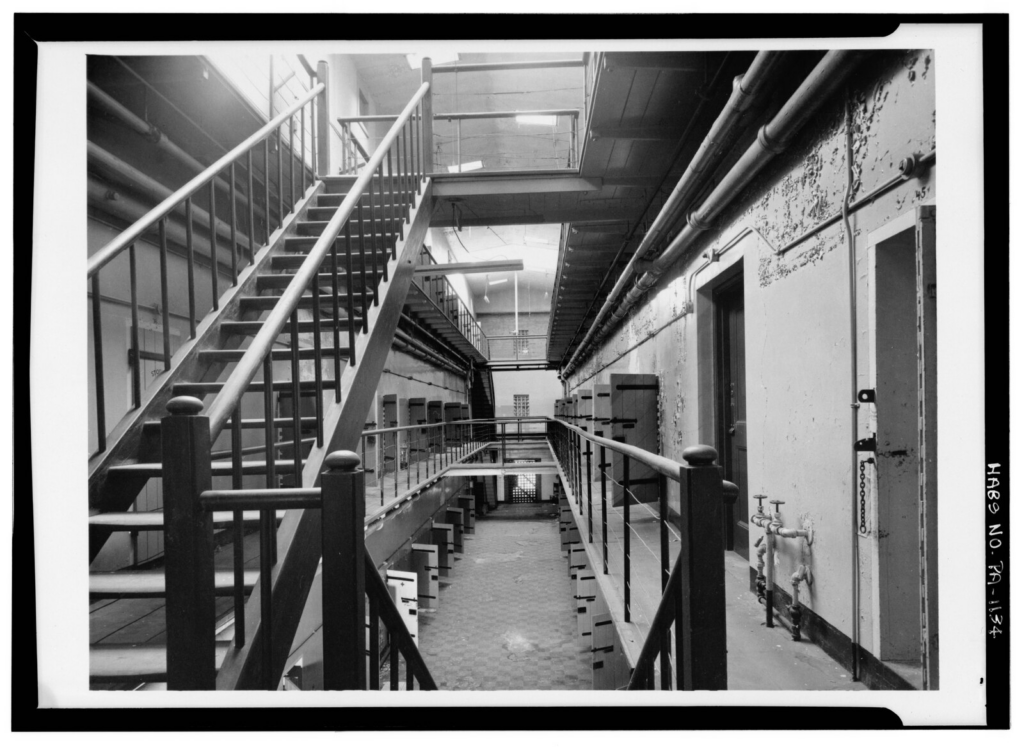

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Carceral Apartheid offers a nuanced study of the BGF and a compelling framework for understanding the U.S. prison system. It also points to some areas for further research. Friedman focuses entirely on men’s prisons, which seem particularly conducive to the kind of violent policing of racial segregation that she documents. But what might a study of “carceral apartheid” in women’s prisons reveal? Regional differences represent another route. While the book focuses on California, Friedman notes that this system of governance was not unique to the state. Prisons across the country adopted similar strategies for managing their populations. The Texas prison system is an excellent example. Historian Robert Chase has written at length about how the state’s building tender or “trustee” system granted certain prisoners enhanced power and privileges that gave way to rampant sexual violence.[3] It would be interesting to explore how these practices differ from place to place.

While the book does contain some disciplinary jargon that may be off-putting to those outside of the academy, Friedman’s interviews—which she quotes at length throughout the book—and her rich narratives anchor the text. In a study that is largely focused on organizational structures and dynamics, Friedman takes care to center the voices of people impacted by these systems. This commitment is also evident in her work as a Principal Investigator of the Captive Money Lab. Founded by Friedman and her collaborators, April Fernandes and Gabriela Kirk-Werner, the Captive Money Lab conducts research and engages in advocacy around the “pay-to-stay” fees that many city, county, and state governments impose on incarcerated people. These findings have informed public policy and signal an ongoing need for research on the criminal legal system.

Carceral Apartheid is an excellent contribution to this literature and offers important context for understanding prisons in the twenty-first century.

Sarah Porter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies twentieth-century social movements, policing, and mass incarceration in the United States.

[1] Brittany Friedman, Carceral Apartheid, 153.

[2] Brittany Friedman, Carceral Apartheid, 166.

[3] Robert Chase, We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.