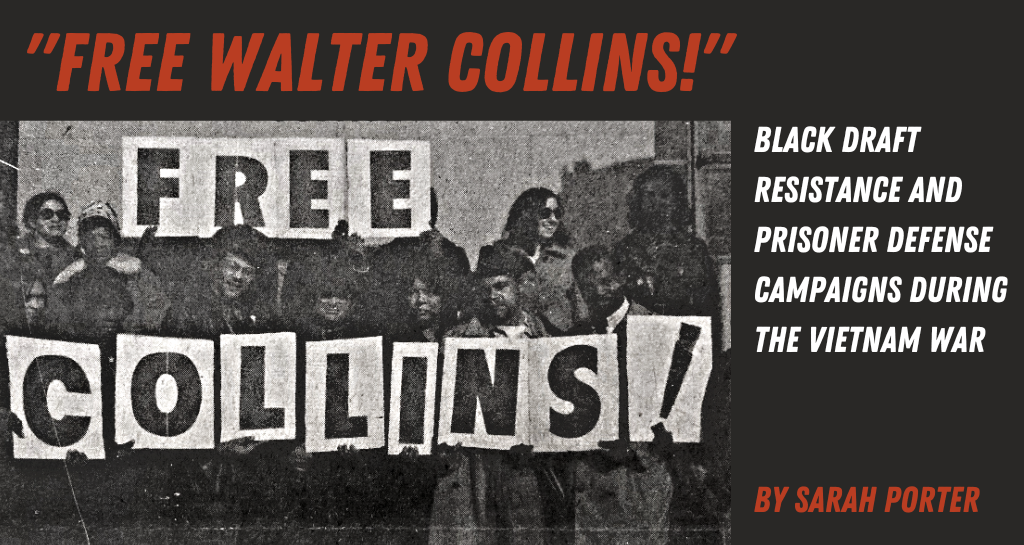

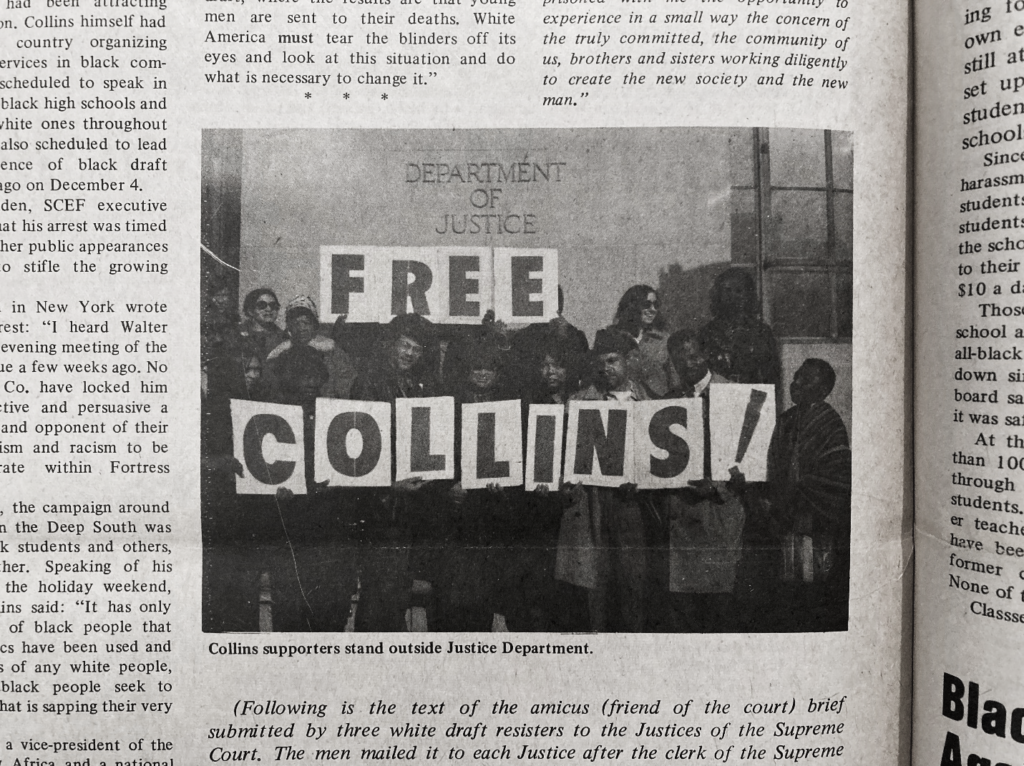

On December 10th, 1970, Dara Abubakari led a delegation of activists to Washington, D. C., where they visited the Department of Justice, the Selective Service headquarters, and the White House.[1] Activists representing a range of civil rights, Black nationalist, and anti-war organizations, including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Republic of New Africa (RNA), and the National Association of Black Students (NABS), participated in the December demonstration. Outside the Department of Justice, one group posed for a photo with signs, which read “Free Collins!” The delegation appeared on behalf of Abubakari’s son, Walter Collins, who had been imprisoned a few weeks earlier. Convicted of refusing induction into the U.S. military based on his opposition to the Vietnam War, Collins was facing five years in prison, even after numerous appeals. With few remaining avenues available for challenging Collins’ sentence in court, his supporters presented their case to individual government officials, and the broader public, in hopes of arousing concern.

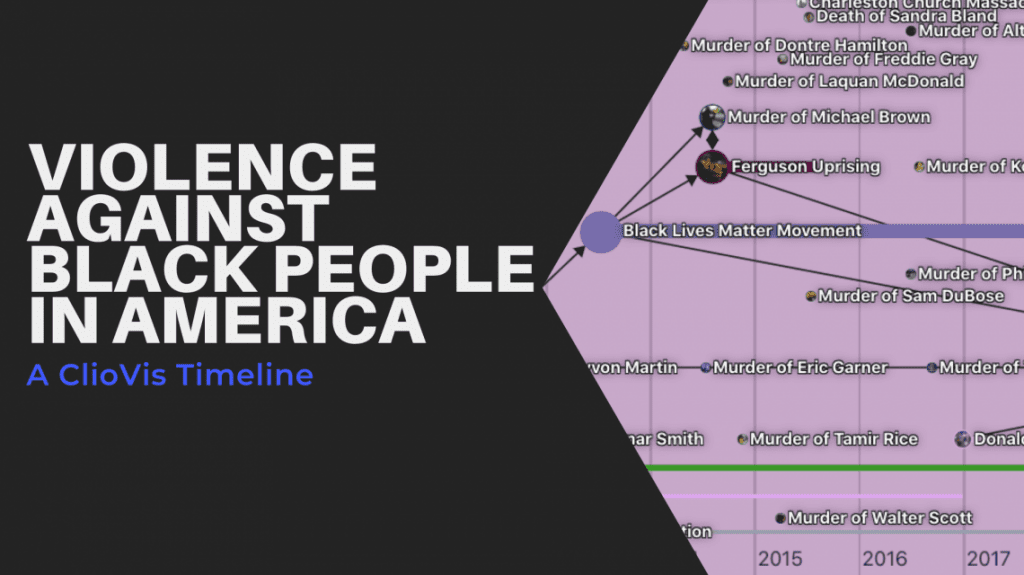

Collins’ legal predicament was not unique. Hundreds of thousands of Americans avoided compulsory military service during the Vietnam War by filing exemptions as conscientious objectors, seeking medical deferments, leaving the country, or simply failing to report for induction—practices broadly categorized as draft evasion or resistance. Of those who refused induction or committed other draft violations, around 9,000 were convicted, and over 3,000 were imprisoned.[2] However, Collins’ legal case and the popular movement that developed around it offer particularly vivid examples of political repression and collective resistance during the Vietnam War era.

Between his sentencing in 1969 and his release from prison in 1972, Collins, his legal team, and his supporters worked tirelessly to appeal his sentence, publicize his case, and mobilize people on behalf of other draft resisters and political prisoners. They petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court, organized public demonstrations, and distributed literature across the country and abroad. Instead of stifling resistance, Collins’ imprisonment actually spurred the development of new campaigns and organizations tailored to advocate for Black political prisoners.

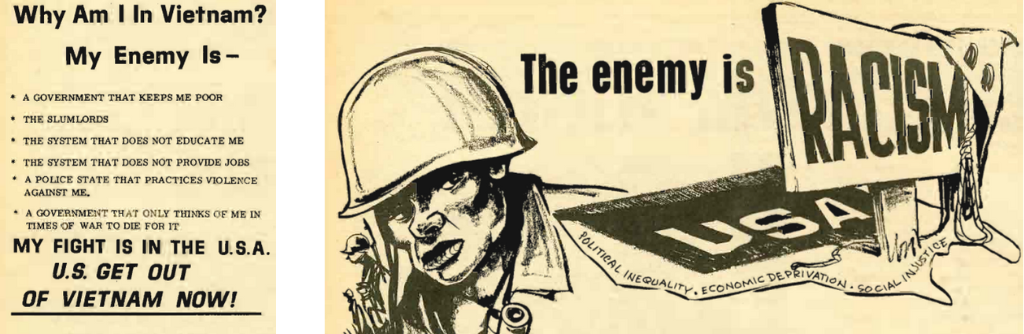

Campaigns around the cases of Black draft resisters like Collins also reveal the particular ways in which civil rights activists engaged in anti-war organizing. Collins’ supporters constructed a large and diverse coalition, and in the process, they developed a critique of the draft as a weapon against movements for social and racial justice. Their campaign blurred the line between foreign policy and domestic politics, revealing how thoughtfully Black civil rights activists situated themselves on the world stage during the 1960s and 70s.

From Civil Rights to Draft Resistance

Walter Collins was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. His family had a long history of involvement in the Southern Black Freedom Struggle. His maternal grandparents, Arthur and Izama Young, were active in the fight to abolish the poll tax, and they helped establish a school system for Black students in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. They belonged to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), one of the nation’s earliest civil rights organizations, and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a group founded by Marcus Garvey on a platform of racial pride and economic self-sufficiency.[3] These groups offered the Youngs and other African American families important organizational structures for challenging discrimination in employment, voting, and education.

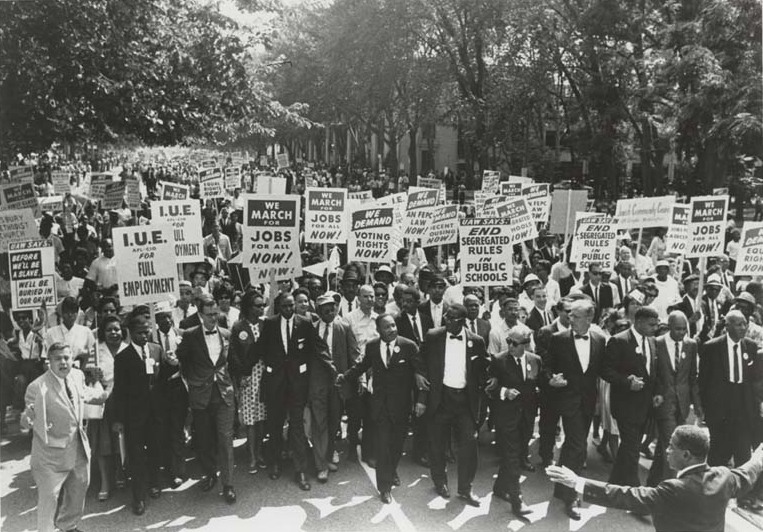

Collins’ mother, born Virginia Young, followed in her parent’s footsteps. She engaged in activism surrounding voting rights, reparations, and police violence, and she participated in landmark events, like the March on Washington in 1963. She held leadership positions in organizations including the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF), an interracial civil rights group, and the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women (UAEW), a Pan-African organization founded by Audley “Queen Mother” Moore. During the late 1960s, she became a regional vice president of the Republic of New Africa (RNA), a Black nationalist organization, and she adopted the name Dara Abubakari around this time.[4]

Walter Collins’ career as an activist began in the early 1960s, when he participated in the New Orleans sit-in movement as a high school student. During the following years, he attended Louisiana State University in New Orleans and worked with groups like SCEF and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to organize communities across the Deep South around issues including voting rights, working conditions, and public education. At the time of his arrest, Collins was active in SCEF’s Grass Roots Organizing Work (GROW) project in Laurel, Mississippi, where he and his colleagues provided support to a local woodcutter’s union.[5]

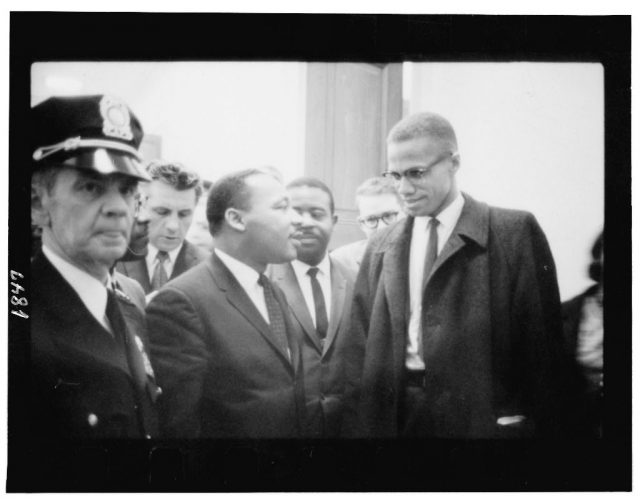

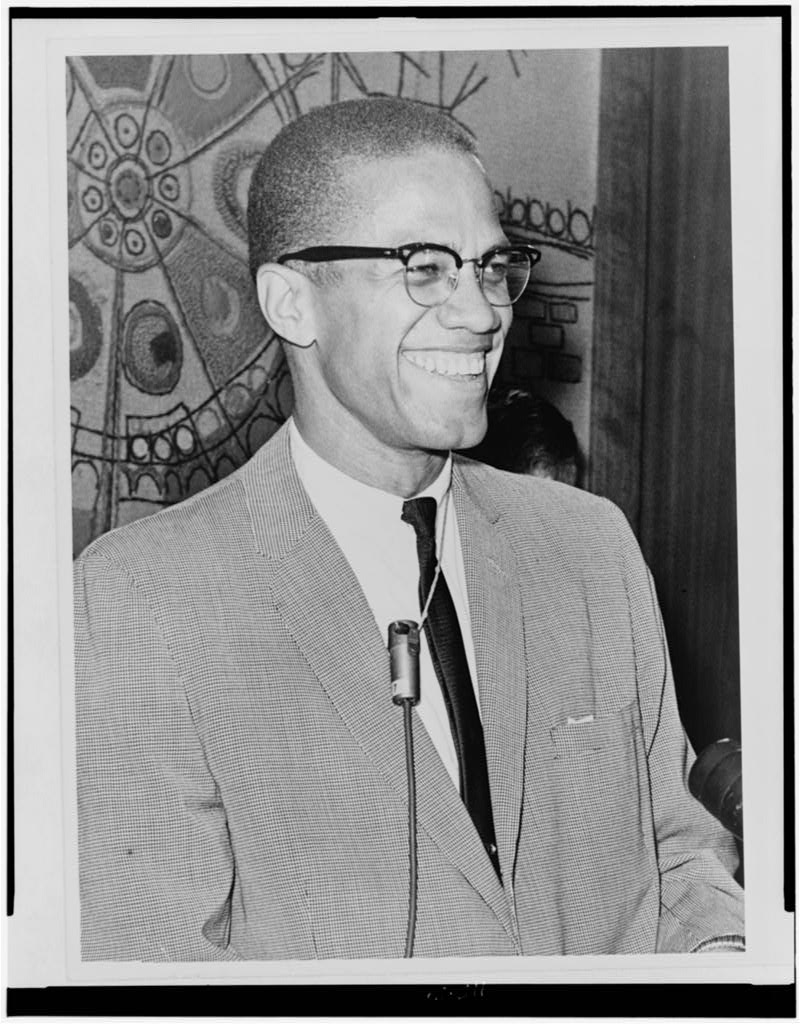

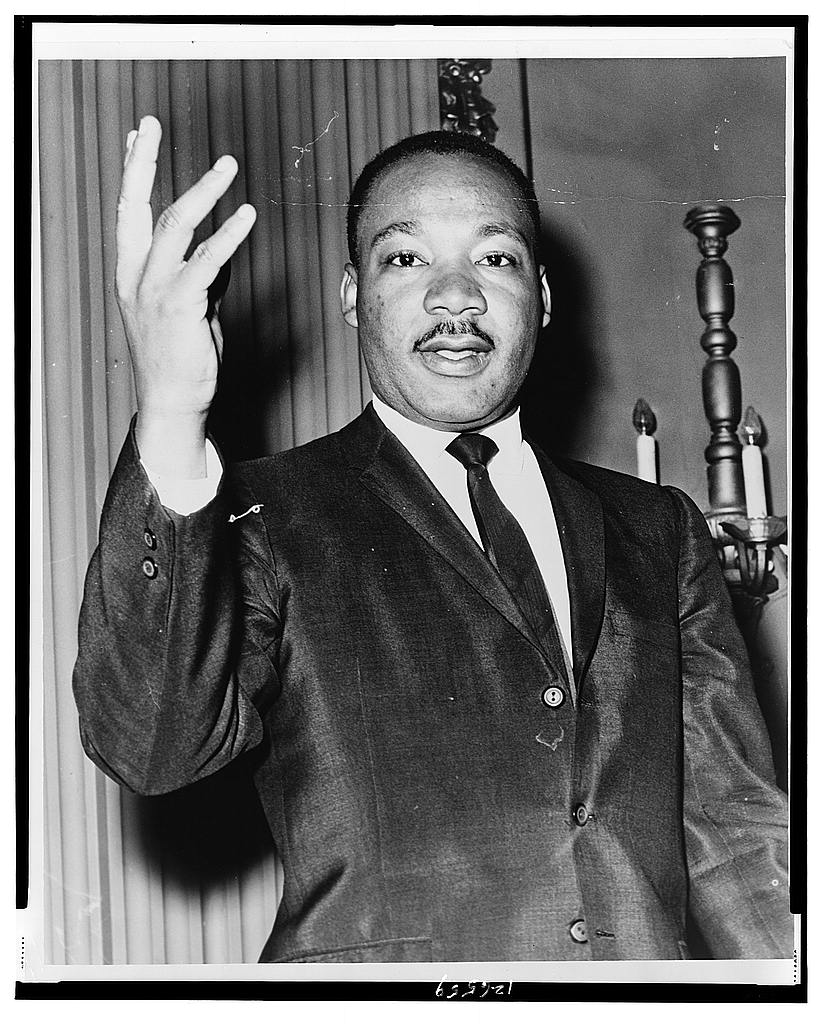

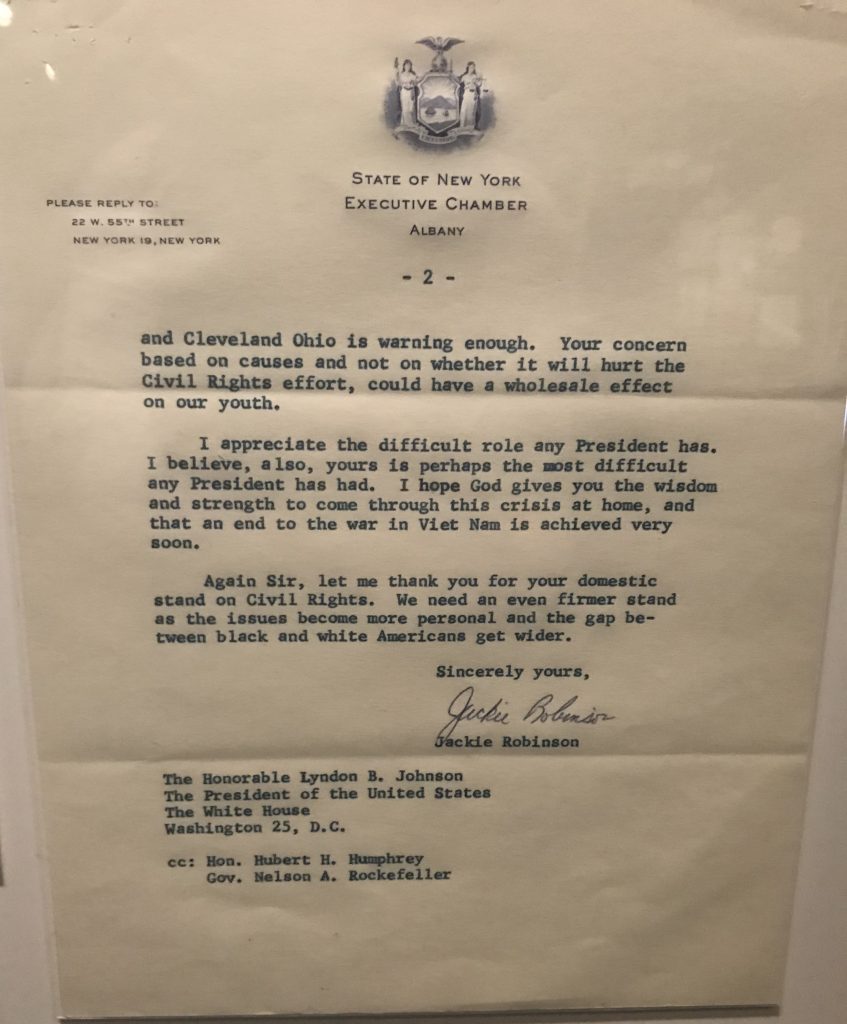

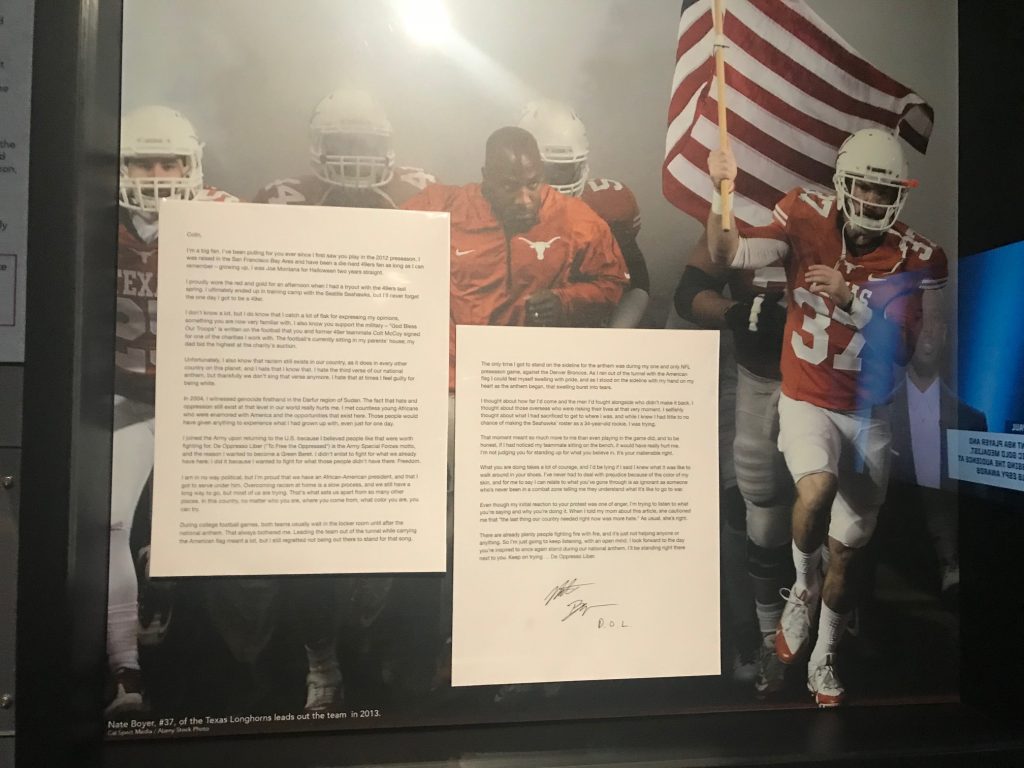

Over the course of the 1960s, as the Vietnam War escalated, Collins became more deeply involved in anti-war activism. In this respect, he was not unique. While the popular imagery of the 1960s and 1970s anti-war movement typically centers on white students, activists involved in civil rights and Black Power organizing were among the most vocal critics of the war. Many viewed American intervention in Vietnam as an imperialist project, and they objected to the enormous financial cost of the war, which undercut domestic programs. The draft also became a major issue, as Black men were overrepresented as draftees and among wartime casualties.[6] Leading civil rights organizations and activists issued statements and delivered speeches condemning the war.[7]

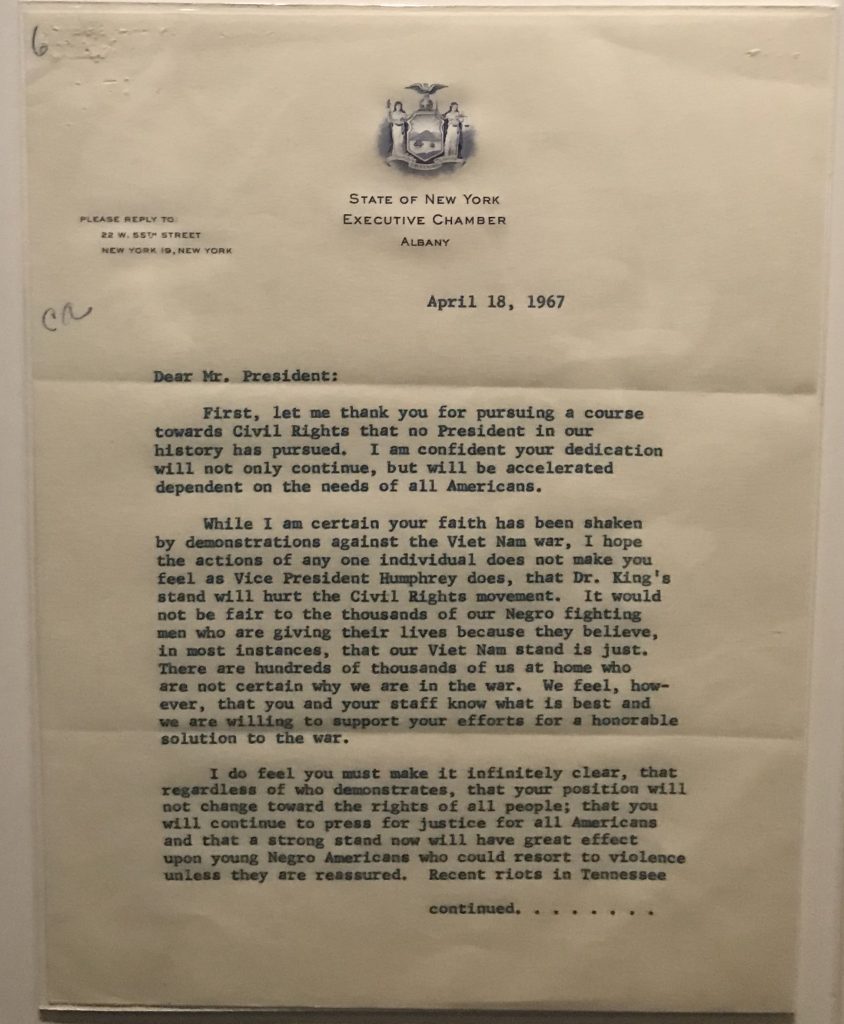

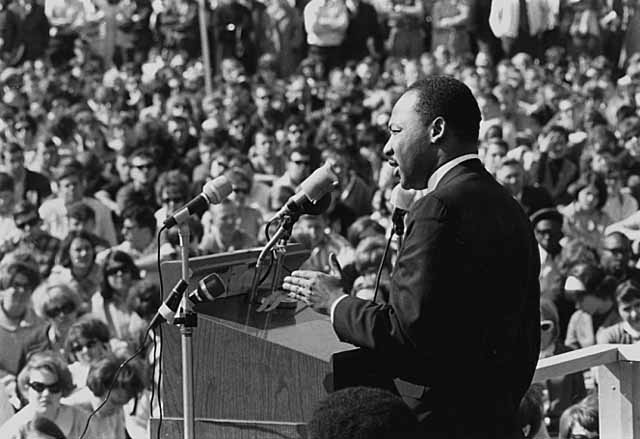

In April 1967, for instance, Martin Luther King Jr. deplored American militarism in a powerful speech entitled “Beyond Vietnam.” Speaking at Riverside Church in New York City, King directed criticism toward the draft, which took “black young men who had been crippled by our society and [sent] them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”[8] Sharing many of these concerns, Collins joined the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (CCCO). He also began providing informal draft counseling to Black students in New Orleans, quickly gaining a reputation for his knowledge on the subject.[9]

Black women like Dara Abubakari also played critical roles in anti-war and anti-draft organizing. They published news articles, created and distributed literature, and established organizations, including the National Black Anti-War Anti-Draft Union (NBAWADU). Some of these women framed their activism in gendered terms and relied on their positions as wives or mothers to claim authority on the subject.[10] Gwendolyn Patton, a NBAWADU founder and SNCC member, laid out this logic in an article published in 1968. She wrote: “If there has ever been a time when we want to know what we can do for the revolution, we can begin now by not allowing this system to draft our sons, our loved ones, our men.”[11] Abubakari consistently used her position as the mother to spark conversations about the war with other women and to advocate on behalf of Collins and other draft resisters.

The Draft as Political Repression

In January 1967, Draft Board 156 in New Orleans reclassified Collins as 1-A, meaning that he was eligible for military service. When he initially registered with the Selective Service System in 1963, Collins received a student deferment. He supplied the required material to confirm his status as a full-time student between 1964 and 1966, but failed to provide this evidence in January 1967, leading to his reclassification. Over the next three years, Collins’ conflict with the draft board intensified. In August 1967, they attempted to send him an induction notice, but it was delivered to the wrong address. After receiving the second notice in September, and learning that he no longer had a student deferment, Collins tried to register as a conscientious objector. While draft officials supplied the required paperwork, they informed him that it was too late to submit it because he had already received an induction notice. Between September and the following March, Collins received four additional notices and failed to report for induction each time. On two occasions, he actually appeared at the induction center, but officials turned him away for wearing an anti-war pin and carrying anti-war literature.[12]

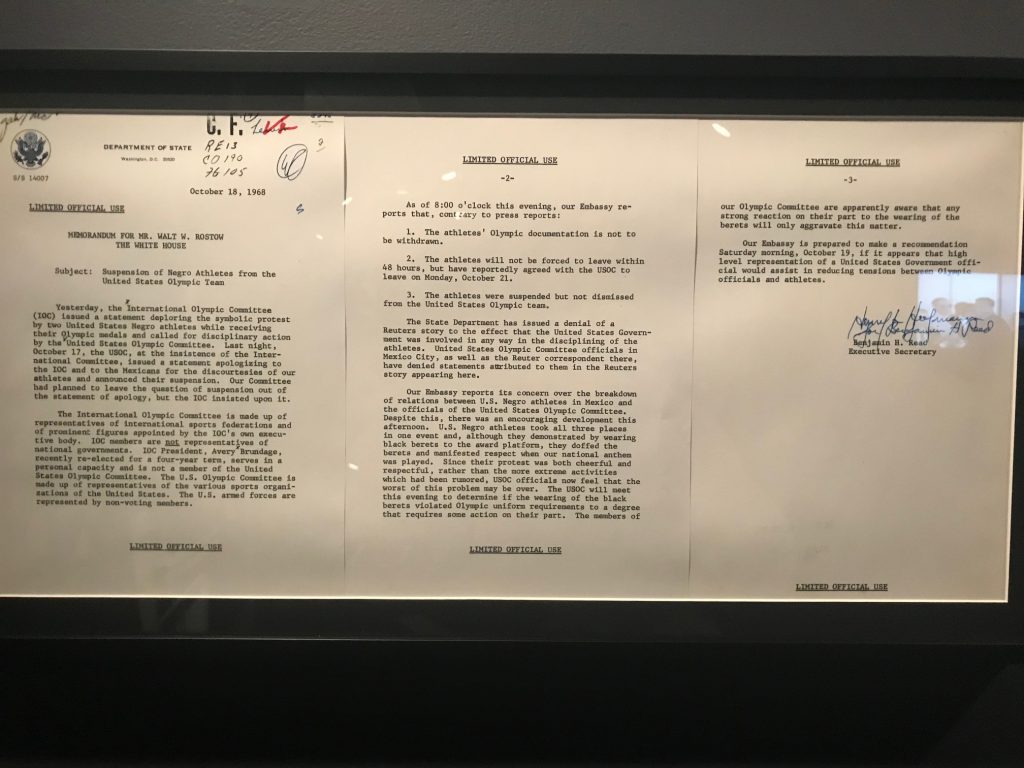

While Collins’ student deferment may have legitimately expired, many of his SCEF colleagues believed his civil rights and anti-war activism had factored into the draft board’s decision. As SCEF Executive Director Anne Braden recounted, Collins’ “trouble with the draft started in the fall of 1966, just after he [had] spent the summer organizing opposition to the Vietnam War in New Orleans.”[13] Many civil rights and anti-war groups experienced heightened government surveillance and repression during the 1960s. Through initiatives like the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Operation CHAOS, government officials illegally surveilled, infiltrated, and discredited civil rights, Black Power, and anti-war organizations. For activists like Collins, it seemed that draft boards were performing a similar function. Numerous activists associated with groups like SCEF and SNCC were drafted during this period. In June of 1967, for instance, SNCC reported that seventeen members had already been indicted for draft resistance.[14] Others were arrested for holding anti-war demonstrations at induction centers.[15] Within this context, Collins’ supporters understood his being drafted as a form of political repression. They viewed him as a draft resister and a political prisoner.

Source: Flo Kennedy, “Harlem Against the War,” The Movement 3, no. 5 (May 1967).

On June 18, 1968, Collins was indicted on six counts of refusing induction. His case came before the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana in July 1969, and the jury found him guilty of five counts of draft evasion. Judge Edward Boyle sentenced Collins to five years for each count—to be served concurrently—and issued a fine of $2,000.[16] Following his sentencing, Collins and his legal team brought the case before the Fifth U.S. Court of Appeals in New Orleans. They focused their case on two key issues. First, the composition of Draft Board 156 violated Section 10(b)(3) of the Selective Service Act. Four of the board’s five members were not residents of the area that it covered, and the chair was not even a resident of Orleans Parish. Other draft resisters had successfully appealed their sentences on this basis. Second, Collins and his attorneys took the argument further by claiming that, regardless of residency, the all-white draft board could not be representative of the majority Black population that it covered. This was a major issue across the country and particularly in the South. In Louisiana, along with a handful of other Southern states, there were no Black members serving on draft boards as of 1966.[17] Despite these efforts, however, Collins’ appeal was unsuccessful.

After the Fifth U.S. Court of Appeals refused to overturn Collins’ sentence in April 1970, his attorneys turned to the U.S. Supreme Court. They filed three petitions in August, November, and December of 1970, but the court ultimately declined to hear the case. Authorities arrested Collins in his home in New Orleans in November 1970 and placed him in Parish Prison.[18] There, he awaited transfer to the federal prison in Texarkana, Texas.

“Free Walter Collins and All Political Prisoners!”

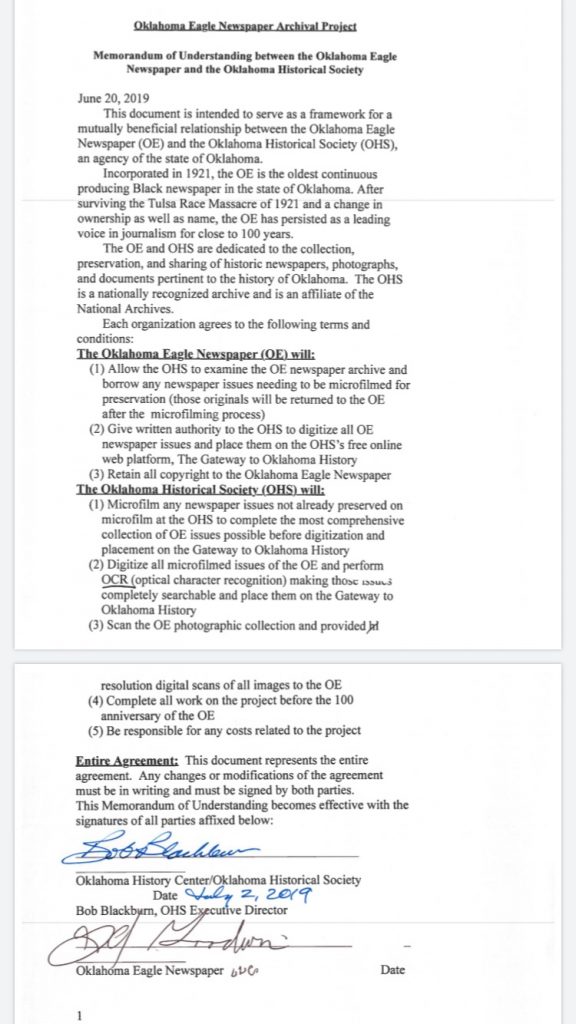

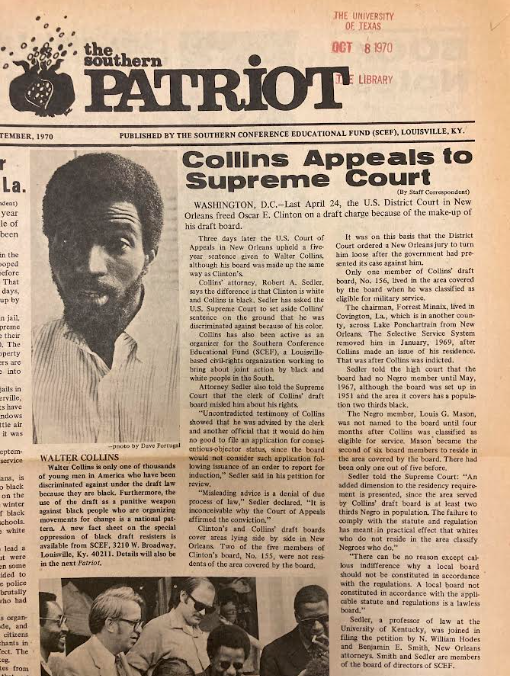

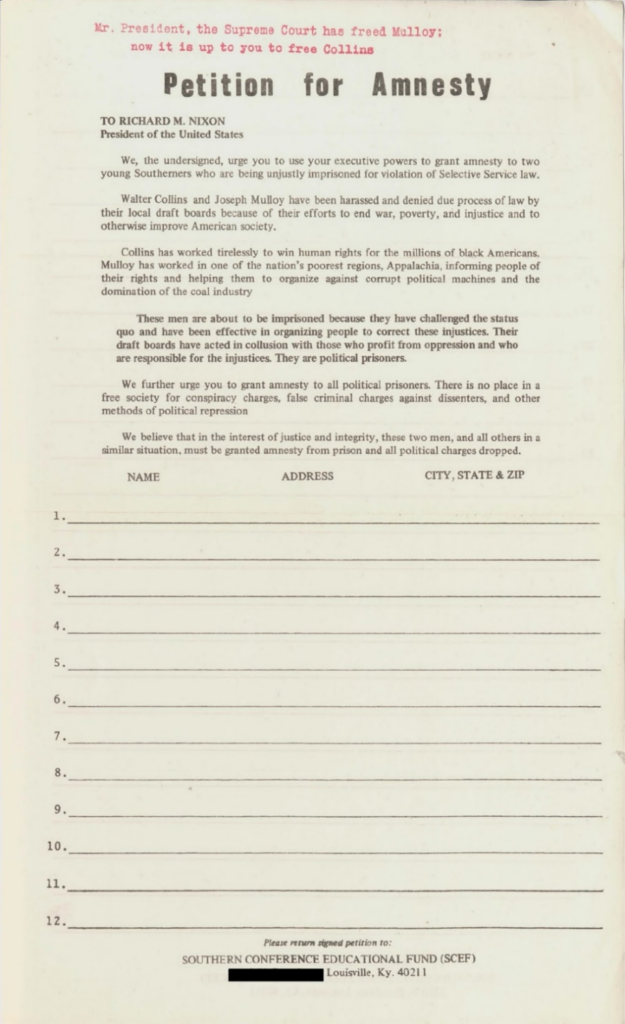

Although Collins’ appeals failed, his supporters continued advocating on his behalf. They circulated petitions, published articles, and organized demonstrations to publicize his case. Drawing from prior experience organizing defense campaigns, Abubakari worked with colleagues in SCEF and other groups to spearhead a popular campaign on Collins’ behalf. In addition to financially supporting his legal defense, SCEF coordinated a publicity campaign around the case in hopes that public protest would pressure officials to reverse his sentence. Articles about Collins frequently appeared in the group’s monthly publication, the Southern Patriot, and in its news briefs. The organization also distributed fliers with information about his case. One flier from 1970 titled “An Enemy of the People” characterized the draft as “a weapon to jail young men who are active in movements against social injustice.”[19] The author urged readers to actively support Collins and other political prisoners by writing to Judge Boyle and contributing funds to the legal defense. SCEF also circulated petitions that accumulated almost 20,000 signatures.[20]

Image courtesy of the author.

While SCEF provided an important base for organizing on behalf of Collins, Abubakari also worked to create a more permanent organization dedicated solely to defending Black draft resisters. On the weekend of March 5, 1971, just a few months after the December demonstrations in Washington, D.C., Abubakari and other delegates reconvened in the national capitol. They congregated at the NABS headquarters and founded the International Committee for Black Resisters (ICBR). The founding members, who included notable activists like Ella Baker and Queen Mother Moore, laid out the following program:

- International support for Black resisters and political prisoners;

- Opposition to apprehension of Black men into the military or into jail for refusing the military;

- Research and communications on the international level about the cases of Black resisters and political prisoners;

- An international Legal Resistance Network;

- Black draft counseling and programmatic planning for high school students;

- “Free Walter Collins” campaign.[21]

In Abubakari’s words, the ICBR aimed to “internationalize the struggle for Black draft resisters and to generate international and national support for their release.”[22] As her statement suggests, ICBR members not only worked to free Collins but also supported larger campaigns to provide amnesty to all Black draft resisters. Collins’ supporters also looked to international forums to publicize the case, and they distributed petitions abroad through organizations like Amnesty International. They understood their project as global in scope and explicitly sought international support for U.S. political prisoners. Although there are few traces of ICBR activities in the historical record after this founding meeting, the group’s platform, and their particular emphasis on the status of Black draft resisters, represented an important intervention within the anti-war movement.

Following the meeting, Abubakari embarked on a cross-country tour with Carl Braden, a longtime civil rights activist and SCEF director. They visited college campuses, churches, and community centers in over forty states to publicize Collins’ case. Abubakari delivered speeches in cities across the United States, including New York, Chicago, Louisville, Austin, and Los Angeles.[23] When asked about her upcoming plans in November 1971, Abubakari emphasized her determination to free her son. She responded, “I’ll finish a whole year of touring and if Walter’s not out of prison by then, I’ll start all over again.”[24]

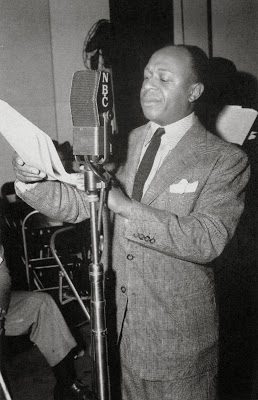

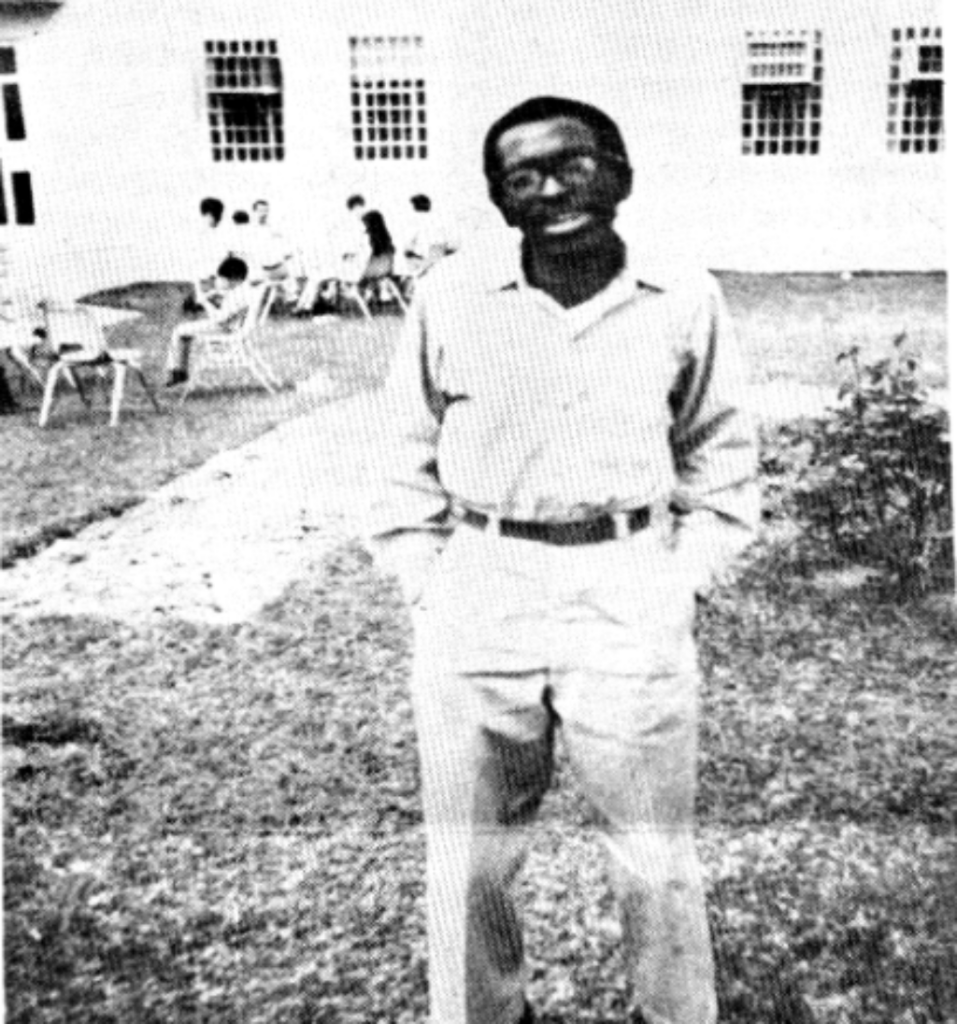

Image courtesy of the Georgia State University Library’s Special Collections Division.

While Abubakari mobilized activists across the country on his behalf, Collins translated his organizing skills to a new context—the federal prison in Texarkana, Texas. While imprisoned, Collins allied himself with fellow inmates to protest mail censorship, corporal punishment, and the lack of adequate medical care in the facility. Firsthand experience with long-term incarceration not only solidified his understanding of his predicament as political repression, but it also brought him face-to-face with the issues that incarcerated people across the nation—from San Quentin to Attica—raised through legal suits, popular protests, and uprisings. During the spring of 1972, Collins became involved in a hunger strike and work stoppage at Texarkana.[25] Although the strike lasted less than a week, newspaper reports reveal that almost five-hundred men participated in the protest. They compiled a list of grievances addressed to Warden Connett and elected a group, which included Collins, to serve as a negotiating team. In response, prison authorities transferred many of the leaders to other facilities and temporarily placed Collins in solitary confinement.

During the fall of 1972, Collins’ parole board recommended an early supervised-release based on “good time” he had accrued while incarcerated. Although Warden L. M. Connett initially refused to free Collins, based on his participation in the strike earlier that year, he eventually complied due to public pressure. After spending two years in prison, Collins was paroled in December 1972.[26] He joined his SCEF colleagues in extending his gratitude to supporters: “Protests from across the nation and around the world helped the warden to change his mind about keeping Collins in prison for an extra five months and voiding his chances of parole. . . . Walter Collins joins the board and staff of SCEF and the editors of The Southern Patriot in thanking all of those who supported him and his fellow prisoners while he was at Texarkana.”[27]

Image courtesy of the author.

Following his release, Collins remained active in campaigns to free draft resisters and other political prisoners. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter granted full pardons to any person who had violated the Selective Service Act between 1964 and 1973. Collins went on to serve as an Executive Director of SCEF and a coordinator for the National Moratorium on Prison Construction in Atlanta, Georgia. During the late 1980s, he returned to New Orleans, and in 1995, at the age of fifty, he passed away after being diagnosed with cancer.[28]

Conclusion

Walter Collins was one of many political prisoners whose legal cases captured national attention and inspired widespread protest during the 1960s and 1970s. Although the individuals and organizations involved in this campaign did not achieve all of their goals—Collins’ eventual release was based on procedure rather than a landmark court case and the ICBR seems to have had only a brief existence—they were able to construct coalitions and develop strategies that could be used in future organizing. Both Abubakari and Collins continued to participate in campaigns to free draft resisters and political prisoners, and they shared the skills they developed with other activists. They led workshops on movement building, spoke at demonstrations, and provided organizational support for other campaigns.

Studying defense campaigns allows historians and community organizers to think more expansively about social movements and their relative success. Defense campaigns were not only logistical solutions to political repression but also represented important sites where participants articulated larger ideas about freedom and justice. Collins’ supporters did not only object to the drafting of conscientious objectors, but to the draft and the war more generally. They understood all draft resisters, and particularly Black draft resisters, as political prisoners, and they used the campaign to free Walter Collins as a space to organize around these issues. By engaging seriously with the ideas that activists involved in defense campaigns put forward and exploring the various strategies that they developed, we can think more critically about their impact over time, while also identifying tools that might be useful in present struggles for racial and social justice.

[1] “Widespread Support Builds For Black Draft Resisters,” Southern Patriot 28, no. 10 (December 1970): 8; Fred Shuttlesworth and Carl Braden to SCEF Board, Advisory Committee and Staff, November 18th, 1970, Anne and Carl Braden Papers, Box 76, Folder 2, Wisconsin Historical Society; “News from Southern Conference Educational (SCEF),” December 11th, 1970, GI Press Collection, 1964-1977, Wisconsin Historical Society, https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/p15932coll8/id/25229.

[2] David Cortright, Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 165.

[3] Ashley Farmer, “Mothers of Pan-Africanism: Audley Moore and Dara Abubakari,” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 4, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 276, 286.

[4] “SCEF Blasts Hoover On ‘Justice’ Remark,” Chicago Daily Defender, November 27th, 1968, 10; “Orleanian Named VP of Republic of New Africa,” Louisiana Weekly, April 19th, 1969, 1; “Women taking deeper look at cause of war,” Daily World, July 19th, 1969, 10; “Republic New Africa’s New Executive Council,” New York Amsterdam News, April 25th, 1970, 3; “Mrs. Collins Is Delegate To Women’s Congress,” Louisiana Weekly, July 25th, 1970, 2; Ashley Farmer, “Reframing African American Women’s Grassroots Organizing: Audley Moore and the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, 1957-1963,” Journal of African American History 101, no 1-2 (Winter/Spring 2016): 87-89.

[5] “SCEF Worker Convicted For Refusing Draft,” Southern Patriot 27, no. 7 (September 1969): 4; “Cancel Summer Vacations For Ballot Fight,” Louisiana Weekly, June 22nd, 1963, 1; Bob Zellner, “Report, Evaluation, and Proposals for the Future,” November 13th, 1970, Civil Rights Vertical Files, Box 159-13, Folder 11, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University; Walter Collins, interview by Kim Lacy Rogers, Part 6, May 20th, 1979, Box 4, Side 2, Kim Lacy Rogers Civil Rights Oral History Collection, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A83107; Kim Lacy Rogers, Righteous Lives: Narratives of the New Orleans Civil Rights Movement (New York: NYU Press, 1993), 20.

[6] Office of Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, “Negroes and the War in South-East Asia,” Anne and Carl Braden Papers, Box 76, Folder 2, Wisconsin Historical Society.

[7] See, for instance: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, “MFDP and Viet Nam,” July 31st, 1965, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/pr/650731_mfdp_pr_vietnam.pdf; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “Statement on Vietnam,” January 6th, 1966, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/snccviet.htm; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “Report on Draft Program,” 1966, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6608_sncc_draft-resist.pdf; Diane Nash Bevel, “Journey to North Vietnam,” Freedomways 7, no. 2 (Spring 1967): 118-128, https://www.crmvet.org/info/67_nash_vietnam.pdf; Flo Kennedy, “Harlem Against the Draft,” The Movement 3, no. 5 (May 1967): https://www.crmvet.org/docs/mvmt/6705mvmt.pdf; Huey P. Newton, “Message on the Peace Movement [1969],” in The Black Panthers Speak, ed. Philip S. Foner (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1995), 67-70.

[8] Martin Luther King Jr., “Beyond Vietnam—A Time to Break Silence,” April 4th, 1967, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkatimetobreaksilence.htm. King’s longtime associate Vincent Harding wrote the original draft of this speech.

[9] “On the Military: Interview with Walter Collins,” Southern Exposure 1, no. 1 (Spring 1973): 6; “SUNO Students To Strike If 10 Demands Are Not Met,” Louisiana Weekly, April 12th, 1969, 1, 7; Marcus S. Cox, “‘Keep Our Black Warriors Out of the Draft’: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement at Southern University, 1968-1973,” Educational Foundations (Winter/Spring 2006): 123-144, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ751764.pdf.

[10] Ashley Farmer, “’Heed the Call!’ Black Women, Anti-Imperialism, and Black Anti-War Activism,” Black Perspectives, August 3rd, 2016, https://www.aaihs.org/heed-the-call-black-women-anti-imperialism-and-black-anti-war-activism/; Rhonda Y. Williams, Concrete Demands: The Search for Black Power in the 20th Century (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2014), 143-146; Lauren Mottle, “‘We Resist on the Grounds We Aren’t Citizens’: Black Draft Resistance in the Vietnam War Era,” Journal of Civil and Human Rights 6, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2020): 26-52.

[11] Gwen Patton, “Black Militants and the War,” Student Mobilizer, January 1, 1968, GI Press Collection, 1964-1977, Wisconsin Historical Society, https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/p15932coll8/id/34169.

[12] United States v. Collins, 426 F.2d 765 (5th Cir. 1970).

[13] Annie Braden, “Southern Group Launches Campaign,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 11th, 1969, 18.

[14] “New SNCC Leaders Outline Their Plans,” Southern Patriot 25, no. 6 (June 1967): 1, 6; “Fred Brooks Refuses Draft,” Southern Patriot 25, no. 11 (December 1967): 4; “‘You Can’t Do This To Me’: Draft Evader Gets 5 Years,” Miami Herald, April 28, 1968, 22-A; “Black Draft Resisters: Does Anybody Care? A Fact Sheet,” undated, Anne and Carl Braden Papers, Box 76, Folder 2, Wisconsin Historical Society.

[15] “SNCC Workers Indicted,” The Movement 3, no. 5 (Spring 1967): 4.

[16] United States v. Collins, 426 F.2d 765 (5th Cir. 1970); “Orleans Man Indicted On Draft Charges,” Shreveport Journal, June 19th, 1968, 12; “Louisiana Man Indicted On Draft Charges,” Daily Advertiser, June 19, 1968, 12; “Collins Is Free On Bond Pending Appeal of Term,” Shreveport Journal, July 10th, 1969, 20; “Sentenced To 5 Years In Draft Case,” Louisiana Weekly, July 19th, 1969, 1; “Jail Black Activist As A Draft Evader,” Michigan Chronicle, July 26th, 1969, 15.

[17] United States v. Collins, 426 F.2d 765 (5th Cir. 1970); “‘Bias’ Charged In New Orleans Draft Case,” Chicago Daily Defender, August 8th, 1970, 20; “US Argues against Collins Appeal,” Southern Patriot 28, no. 9 (November 1970): 5; News Release, Office of Public Information, Selective Service System, December 16th, 1970, Anne and Carl Braden Papers, Box 76, Folder 2, Wisconsin Historical Society, 6.

[18] United States v. Collins, 426 F.2d 765 (5th Cir. 1970); Walter Collins v. U.S., 400 U.S. 919 (1970); “Court Upholds Charges Against Walter Collins,” Louisiana Weekly, May 9th, 1970, 9; “Court Rejects Challenge Of Draft Board Alignment,” Town Talk, November 16th, 1970, 4; “Judge Boyle Refuses To Cut Draft Resister’s Term,” Louisiana Weekly, February 27th, 1971, 5; “Nab La. Activist on draft dodge rap,” Chicago Daily Defender, December 1st, 1970, 4; “24-year-old draft activist arrested to serve 5 years,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 12th, 1970, 16.

[19] Southern Conference Educational Fund, “An Enemy of the People,” GI Press Collection, 1964-1977, Wisconsin Historical Society, https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/p15932coll8/id/61302/rec/148.

[20] Southern Conference Educational Fund Revenue and Expense Operating Fund, June 30th, 1970, Civil Rights Vertical Files, Box 159-13, Folder 11, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University; Southern Conference Educational Fund, “An Enemy of the People,” GI Press Collection, 1964-1977, Wisconsin Historical Society, https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/p15932coll8/id/61302/rec/148; “20,000 petition Nixon for black,” Chicago Defender, February 17th, 1971, 27.

[21] “International Black Draft Resisters Committee Formed in Washington,” Sun Reporter, March 20th, 1971, 13; “Draft Resisters Group Formed,” Los Angeles Sentinel, March 25th, 1971, A2; “Draft Resisters Organize in Washington,” Sacramento Observer, March 25th, 1971, C10; “Group organized to aid black draft dodgers,” Chicago Daily Defender, April 10th, 1971, 14.

[22] “International Black Draft Resisters Committee Formed in Washington,” Sun Reporter, March 20th, 1971, 13.

[23] “Lawman Guest Speaker,” New York Amsterdam News, April 17th, 1971, 28; “Freedom for draft resisters,” Chicago Daily Defender, October 23rd, 1971, 18; “Foe of draft to speak,” Courier-Journal, May 16th, 1971, 24; “Interracial Officials Due at UT,” Austin Statesman, June 14th, 1971, 8; “Prisoner’s Mother Guests,” Los Angeles Sentinel, November 11th, 1971, B6.

[24] Jean Murphy, “Lifelong Battler in Struggle to Free Jailed Draft Resisters,” Los Angeles Times, November 14th, 1971, D3.

[25] “Inmates End Strike At Texarkana Prison,” Corpus Christi Times, April 12th, 1972, 11; “Men Strike in Texarkana,” Southern Patriot 30, no. 5 (April 1972): 6; “News from the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF),” May 10th, 1972, 1; “Collins Letters on Revolt,” Southern Patriot 30, no. 5 (May 1972): 6; “Federal Prisoners Protest,” San Antonio Register, July 7th, 1971, 7.

[26] “Walter Collins’ Parole in Doubt,” Southern Patriot 30, no. 8 (October 1972): 8; “Collins Wins Release,” Southern Patriot 30, no. 9 (November 1972): 8; “Draft Resister Freed One Month Late,” New Pittsburgh Courier, January 6th, 1973, 22.

[27] “Collins Wins Release,” Southern Patriot 30, no. 9 (November 1972): 8.

[28] “New executive director of SCEF is named,” Courier-Journal, December 12th, 1973, 12; ; “Statement of Walter J. Collins, Coordinator, National Moratorium on Prison Construction,” in Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives (Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 125, https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/88401NCJRS.pdf; Jeanne Friedman, “Fallen Comrades: Walter Collins,” http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=305.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.