Latin American popular culture presents two common tropes about Spanish colonial rule. One is the representation of viceroys as autocrats who ruled without any institutional constraint. This perception “explains” the authoritarian tendencies of Latin American societies in the postcolonial period. The other trope ironically undermines perceptions of authoritarian control by highlighting the margin of discretion that colonial officials enjoyed in the application of the law. One example of this flexible interpretation of the law is a famous phrase uttered by the Spanish American bureaucrats when a royal order came from the metropolis: “I obey but I do not comply” (obedezco pero no cumplo). Officers used this prerogative in some cases to avoid enforcing certain royal policies that they thought might be harmful for the territories in the New World where they ruled in representation of the king. This trope “explains” the apparent disregard of modern Latin Americans for the law. Neither of these representations of colonial rule is accurate.

Alejandro Cañeque’s The King’s Living Image invites readers to reconsider many of the misconceptions about Spanish America found in Latin American popular culture. Cañeque argues that we cannot understand the colonial Spanish bureaucracy with our modern conceptions of the state. In fact, Cañeque refutes the centralizing and autocratic vocation of the Spanish Monarchy for most of the colonial period (until the beginning of the eighteenth century) because those elements associated often with the modern state simply did not appear there. Without a standing army and an extended and centralized bureaucratic apparatus, how did Spain rule over almost a whole continent? Central to the author’s argument is that political beliefs and institutional practices were crucial in sustaining viceregal power and colonial rule. Spaniards imagined the state as a human body in which each body part (institution) played a key role in the system. The king represented the head, but even a king could not move if his legs did not respond. At the institutional level, the king could not procure good governance in the kingdom without the help of his most trusted councilors working in those institutions. The collective action of the whole created a sense of community among all its members.

Cañeque reinforces this idea by stating that political power was transmitted from God to the community, which then transferred it to a king. Thus, the monarch had the absolute obligation to rule for the benefit of the people and the common good. Justice and good governance became the ideological foundations of the Spanish Monarchy. Their fulfillment depended on the cooperation of the head and the different body parts. Shattering misconceptions about despotism in the Spanish Monarchy, Cañeque claims that this system of government had its analogy in heaven, where God was assisted by the Seraphim, who had the job of purging, illuminating, and perfecting the hierarchies below them. In this framework, the author analyzes the administrative hierarchy in Spanish America from the upper echelons to the local forms of government. Through his study of Viceroyalties, and Audiencias and Cabildos, Cañeque shows how the Spanish Monarchy was structured in a way that any site of power reflected a higher level.

Cañeque focuses in the figure of the viceroy, who represented the living image of the king, playing the role of the head of the political body in Spanish America. Mirroring the celestial court, viceroys had to be exemplary rulers for their subjects. Like the king, they had to rule by virtue, and not by force. If we add to this their mission of dispensing justice, we now can understand the famous phrase “I obey but I do not comply.” Viceroys and other colonial officials did not enforce certain royal policies when they were thought to be contrary to the justice and the laws of the kingdom. Certainly, they could abuse this prerogative for other goals, but its purpose was not the disregard of the law but the protection of the larger conception of justice.

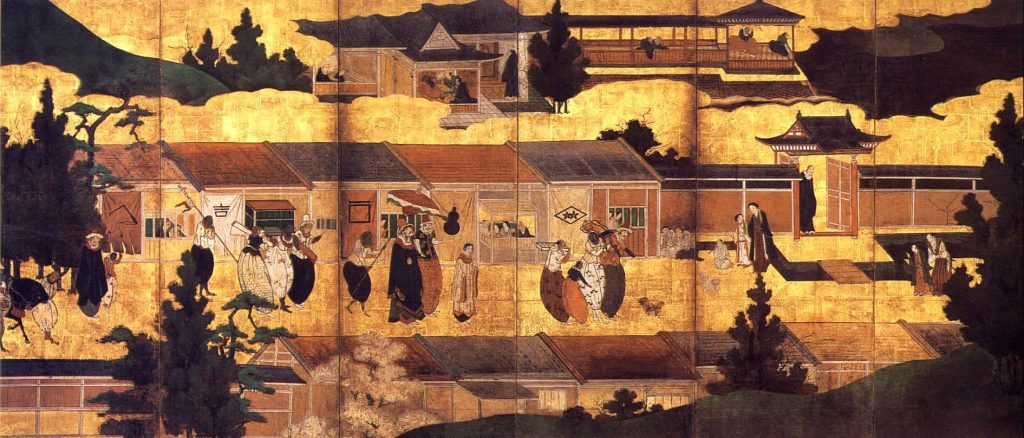

If the viceroy represented the living image of the king, how did the king project his power through the viceroy? Symbolic representations, such as triumphal arches, processions, and the magnificence and pomp in the viceroy’s public appearances, all constituted and sustained viceregal power. People today would see mere spectacle and vanity. But these were the means through which authority was legitimated, especially when coercion on a grand scale was simply impossible. Symbols and political rituals were fundamental for the legitimization of power. Consider modern states and their use of symbols to command respect and loyalty. Think about the purpose of national hymns, or the splendor of national parades. Allegiance to the nation’s flag evokes the same feelings that people would have experienced by seeing the public appearance of the king’s living image in the figure of the viceroy.

Cañeque’s The King’s Living Image is a readable and well researched contribution that serves as a wake-up call to reexamine many of the misconceptions that have informed Latin American popular culture about Spanish American colonial power.

You May Also Like:

The Archeology and History of Colonial Mexico

Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico