by Horus Tan

The People’s Commune was both a collective farm and a local institution that managed almost all economic and political activities in rural China. It was introduced in China in 1958 and abolished in 1983. Many scholars suggest that the People’s Commune was unproductive because its remuneration system was too egalitarian. According to James Kai-sing Kung , it offered only “a tenuous link between effort and reward. This weakness of incentives led to extensive free-riding behavior, which was cured only by the eventual replacement of the collectives by family farms.”[1] The Chinese Communist Party today shares this perspective. In its official narrative, the People’s Commune was too unproductive to maintain the subsistence of the peasants, and the abolition of the commune was set into motion by a couple of destitute peasants in 1978 who were attempting to improve their living standard. Joshua Eisenman offers a quite different perspective. In Red China’s Green Revolution, he argues that, instead of being an economic failure, the People’s Commune was successful in modernizing agriculture and promoting agricultural productivity during the 1970s. Some top officials of the Chinese Communist Party, not some poor peasants, abolished the People’s Commune in 1983 for their own political gain instead of its economic performance.

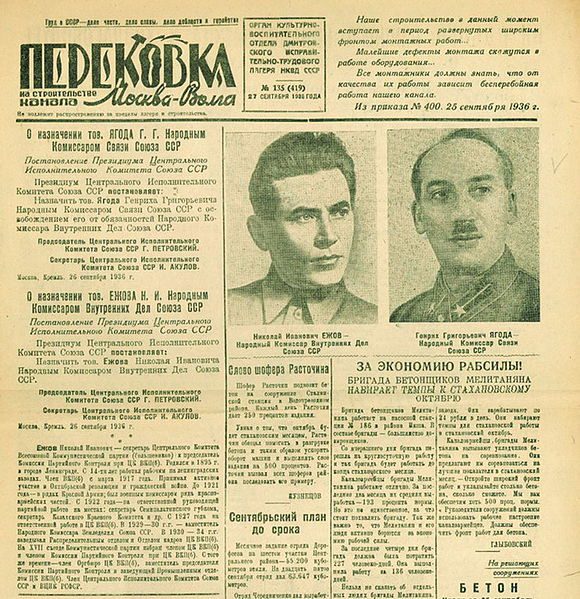

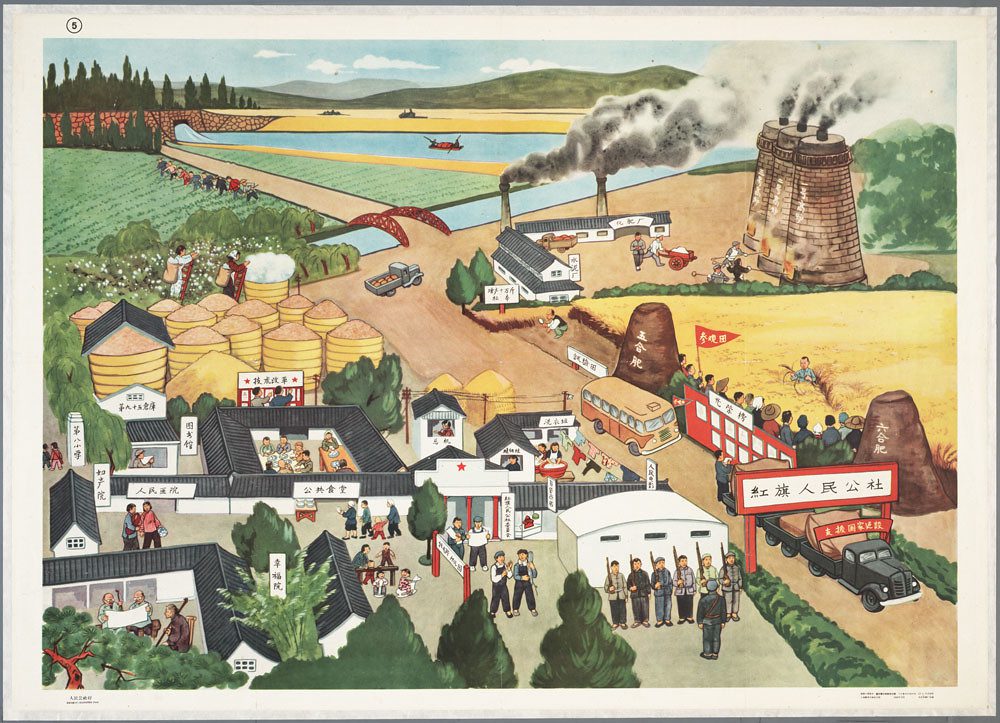

Poster of People’s Commune ca. 1958 (via Flickr)

Eisenman’s foremost conclusion is that the People’s Commune of the 1970s can be considered productive because of its ability to generate investment. Eisenman found that the People’s Commune was not a rigid institution. When it was introduced in 1958, it was indeed a disastrous failure and led to the famine of the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961). However, it experienced a dramatic transformation in the 1960s. By the 1970s, the People’s Commune, which Eisenman called the “Green Revolution Commune,” was successful in raising the agricultural productivity in China. One of the biggest problems agriculture in China faced before the introduction of the People’s Commune was the lack of capital. In a country with scarce capital and an unlimited labor force living just above subsistence level, it was hard to cut consumption and increase saving rates, in order to make productive investments to take advantage of high returns to capital. The People’s Commune of the 1970s extracted agricultural surplus before produce was distributed among the peasants. In other words, the peasants were taxed before they got their income. This system enabled the commune to “reduce consumption and ensure the high savings rates necessary to finance agricultural modernization.” Unlike the People’s Commune of 1958, which invested household savings in poor quality capital and caused the most catastrophic famine in human history, the People’s Commune of the 1970s turned savings into productive investments like agricultural machinery and chemical fertilizer. It kickstarted a continuous development process that produced rapid growth in food production. At the same time, the People’s Commune of the 1970s tolerated the existence of private sideline plots, cottage enterprises, and rural markets. This tolerance helped the peasants maintain their lives above the subsistence level and avoid the over-extraction which took place in the People’s Commune of 1958.

Mao Zedong shakes hands with Peoples commune workers ca. 1958 (via. Wikimedia)

Many scholars suggest that the remuneration system of the People’s Commune allowed the less productive members to be free riders, and made more productive members work less hard for the commune and seek better compensation outside it. In contrast, Eisenman argues that the free rider problem was largely alleviated by Maoist collectivist indoctrination. He argues that the People’s Commune was a kind of religious community, a church of Mao. Through ceremonial behaviors, like the public recitation of Mao’s teachings, the performance of Maoist opera and dance, and the display of Mao’s profile, the People’s Commune created a self-disciplined labor force who prioritized the fulfillment of Maoist collectivist ideology over material wealth. These activities also created a strict political atmosphere in which a nonconformists felt that criticized by the entire commune. Maoist indoctrination was backed up by the People’s Militia—the semiautonomous local military institution nested within the commune. The People’s Militia was controlled by the leaders of the commune to enforce both the commune’s collectivist ideology and its external security. Eisenman points out one additional characteristic that forced peasants to accept the high savings rates. The People’s Commune was not only a collective farm but also an autarkic institution that managed almost all economic and political activities in rural China. This autarky made it almost impossible for the peasants to flee the commune and seek a better life in the world outside.

People’s Commune Canteen ca. 1958 (via Wikimedia)

Eisenman’s second major conclusion is that the abolition of the People’s Commune was carried out by top officials of the Chinese Communist Party. According to the official narrative, the People’s Commune was too unproductive to maintain the subsistence of its members, so eighteen starving peasants in a commune of East China decollectivized their own commune, risking the death penalty on December 24, 1978. The improvement of these peasants’ economic conditions after decollectivization supposedly encouraged the authorities to abolish the People’s Commune. However, Eisenman argues that the fate of the Commune was decided not by its economic performance or by grassroots demands, but rather by the winner of the factional struggle within the Communist Party—Deng Xiaoping. The abolition of the Commune was a deliberate decision taken by these top Party officials to overthrow their pro-commune rivals who were still loyal to Mao’s ideology after Mao’s death. He also shows that there were many local and commune officials who opposed the abolition of the commune and refused to return to household-based agriculture. They did not dismember their commune until they were asked to do so by provincial officials. Some provincial officials admitted that they had to issue orders to stop the local officials from hindering the decollectivization movement.

People’s Commune ca. 1981 (via Wikimedia)

One of the merits of Eisenman’s study is that it offers a very useful approach to help scholars understand the transformation of agriculture in China during the 1960s and 1970s. Famine is one of the most common topics in Chinese history, and agriculture in China still underperformed until the 1960s. But during the 1970s, the situation definitely changed. Between 1962 and 1978, although China was almost completely closed to foreign trade, added almost 300 million people without suffering any massive famine. We can’t understand how Chinese agriculture accomplished this if we do not recognize the contribution of the People’s Commune to agricultural productivity. Eisenman’s study also helps researchers to dispense with their idealization of private property rights. Researchers of collective agriculture in the Soviet Union and Communist China usually are occupied with the underperformance of collective agriculture and the tragedies peasants suffered in the collective farms in these countries. These tragedies sometimes make researchers assume that private property is therefore superior. Eisenman’s study shows that the foremost obstacle faced by agriculture in many developing and underdeveloped countries is the lack of capital rather than the lack of private property rights. Small peasants cannot overcome the lack of capital by just building a closer connection between effort and reward.

![]()

[1] James Kai-sing Kung, “Transaction Costs and Peasants’ Choice of Institutions: Did the Right to Exit Really Solve the Free Rider Problem in Chinese Collective Agriculture?” Journal of Comparative Economics 17, no. 2 (June 1993): 486.

![]()

You might also like:

Confucian Patriarchy and the Allure of Communism in China

China Today: Communism for Americans in the 1930s

The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past, by Gail Hershatter (2011)

Sowing the Seeds of Communism: Corn Wars in the USA

![]()