It’s usual when hearing the word “lowrider” to imagine a car, lifted just barely above the road by wheels with stylized rims, and probably an impressive paint job and hydraulic system. Alongside this meaning, lowrider also refers to an entire culture and community that surrounds the customization and competition of cars, bikes, and anything else that can be converted to fit the lowrider aesthetic. Lowriding is a culture rooted in Mexican American communities with southwestern influences, that values family, community service, creativity, and dedication. This phenomenon has given rise to numerous car shows and competitions across the nation, and internationally, all with the goal to inspire and encourage lowriders to “create cars that push the limits of what a car can be.”

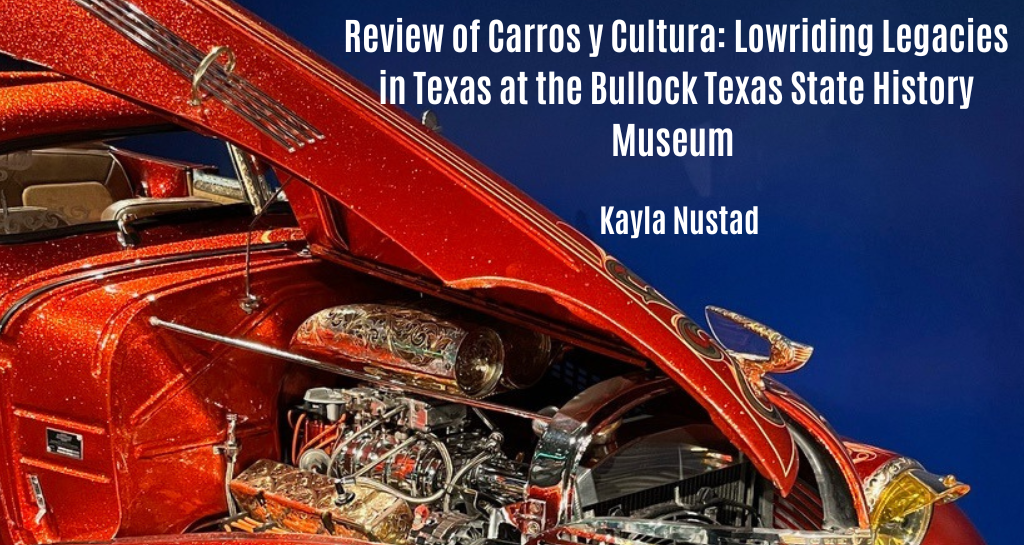

At the Bullock Texas State History Museum, Carros y Cultura: Lowriding Legacies in Texas, is on display until September 2nd, and it’s one cruise that should not be missed. Immediately when walking through the exhibit entrance, you’re struck by color and creativity. Large banners hang from the ceiling displaying words that encompass what it means to be a lowrider: community, character, creativity, family, artistry, dedication, style, respect, culture, skill, identity, “con safos”, valor, passion, and pride. These embody the values of the car club community. Approaching each item, whether it be a modified bicycle, or a car painted to resemble a mural, the values become clear from the level of detail, dedication, and familial story each piece needed to become the museum-worthy work it is today.

Lowriding originated in California after the end of World War II as a conveyor of cultural expression and as a reflection of Mexican American identity. At the time, the cultural movement was heavily associated with the Chicano civil rights movement, which resulted in city laws targeting the lowriding cars by restricting car height. The restrictions didn’t deter the lowriders, who cleverly adapted by installing hydraulic systems that let them raise the cars to a legal height for driving, then lower them for cruising. This creative solution to the targeting laws became a beacon of lowriding culture and is embedded in competitions and shows as a testament to the skill of designers.

After a resurgence in the 1970s, lowrider culture expanded outside of California, reaching the rest of the Southwest region and Texas. Soon, car clubs began popping up in West Texas cities such as El Paso and Odessa that are through points of traffic flowing from Texas, California, and Mexico. The club and car culture continued to grow throughout Texas, and soon reached relevance in pop culture and media. Publications like Lowrider Magazine gave the community a unified voice, while lowriders gained visibility in movies and music. Eventually, the community activity reached formal competitions and car shows, bringing lowriding into the mainstream auto industry and cementing the culture’s relevance in a new audience. Lowriding has expanded its reach past the U.S. borders, with shows taking place all over the world.

Community is a major tenet of lowrider culture, and this can be seen through the more than a thousand official car clubs that support the culture and maintain its connections throughout the country. Lowrider Magazine has a registry of over 1,300 clubs today, but this is a low estimate of the true number of clubs that individuals and families run on their own. Each of them has an individual story and identity: some choose to focus on a certain style of car (the Chevrolet Impala is one of the most popular models to customize), and some base their membership on shared values. All seek to serve their communities and sustain their culture through familial connections and positive, respectful environments. Clubs can serve the community in a variety of ways, including raising money for charities and providing collective family friendly gatherings for small towns and neighborhoods. In Austin specifically, the club Highclass Austin works to help less fortunate children through hosting an annual holiday toy drive for orphans in Mexico.

1963 Chevy Impala courtesy Raul Rodriguez Jr., Round Rock

One of the earliest lowriding car clubs in Texas was founded in the 1970s by Nick Hernandez, a legendary lowrider from Odessa, Texas. The club, Taste of Latin, had 14 chapters across the state at its peak of popularity, and aside from showcasing the various creations of the lowriders, acted as a vocal outlet for Mexican American civil rights. Nick Hernandez is also the father of America’s longest running lowrider car show, the Tejano Super Show, which began in 1972. One of Hernandez’s personal cars was a 1964 Impala called the “Odessa Masterpiece,” which helped grow the Taste of Latin’s reputation for customized paint schemes. The iconic piece, the hood mural, was featured in Lowrider Magazine in 1980, and recognized in Texas Monthly as Best Lowrider in 1985. The mural features a dual-paned painting centered around two blue fairies set in a grassy waterscape, and colorful striped detailing framing the hood.

Since family is a strong tenet of lowrider culture, most car club gatherings take place on Sunday afternoons, with activities such as picnics, car shows, and cruises. Familial bonds are strengthened through time spent together, but also teaching the art of customization to the next generation. A lowrider child’s first introduction to the culture is often a Taylor Tot stroller, vintage strollers with custom paint jobs, or a custom pedal car, both displayed alongside the full-size cars in the exhibit to emphasize the intergenerational connections of lowriding. Lowriding, the exhibition tells us, is something that runs in the family, and parents who participate in the culture encourage their children to find their own ways of creative expression by teaching them lowriding techniques. A phenomenon that began as a way for children to engage with the culture, working on bikes allows parents to pass lowriding values and skills to their children, and inspires them to build their own personal connections to the culture and the craft.

1984 Chevy Monte Carlo “La Mera Mera” courtesy Mercedes Mata, Dallas

The cars themselves are the true marvel of the exhibition. Lowrider cars are extraordinary vehicles for personal expression, and the two Chevrolet Monte Carlos on display are of the most eye-catching of the group. One, “La Mera Mera,” is a dazzling pink 1984 Monte Carlo designed by third-generation Dallas lowrider, Mercedes Mata. This car features a custom pink interior, molding, exterior, and even a heart-shaped chain steering wheel. The hood’s mural depicts the creator, Mercedes, with the backdrop of her hometown’s skyline, honoring its importance to her and her family. Mercedes cemented her place in the Dallas community as the youngest woman to build her own lowrider, and she continues to advocate for other female lowriders as well as for mental health through her social media presence.

The “Blue Monte” is one of the most impressive parts of the exhibit, boasting more than thirty years of different major paint jobs and customization, and numerous awards and accolades from Lowrider Magazine. The intense dedication and work put into this car is obvious from the second one lays eyes on the Monte Carlo car, and it is difficult to put into words how stunning the artwork is. Blue Monte’s base is a sparkling royal blue paint topped with a rainbow of stripes and geometric line work that make this car truly unique. The mysticism does not end with the paint; the entire interior of the convertible is covered with a vibrant golden crushed velvet, which is also found in the trunk surrounding the hydraulic motor. Gold and reflective details are found all around the car, from the mirrored doors and center console, to the rims and engraved bumpers. And resting on top of the rear center console is a miniature version of the Blue Monte—a testament to the car’s place in lowrider pop culture.

Blue Monte’s owner and designer, Chuy Martinez, is as much an icon to the lowrider community as the car itself. He has been an active member of Laredo’s lowrider community since he was 15 years old. Quickly becoming a prominent member of one of the oldest Texas lowrider clubs, Brown Impressions, Martinez has held the position of club president since 1982. When Martinez became the owner of the car that would become the infamous “Blue Monte,” he knew he wanted to create something that was completely unique to himself, and in 1990 he began this process by turning the car into a convertible. This iconic duo of car and designer has earned numerous show awards at car shows, including Best Full Custom, Best Metal Engraving, and even Best Lowrider of All.

1975 Chevy Monte Carlo courtesy Chuy Martinez, Laredo

The cars and bikes not only represent a personal creative output, but reveal deep ties to Texan and Mexican culture through artistic expression. Under a front spotlight at one of the exhibit’s entrances rests the “Still Texas,” a 12-inch 1972 Schwinn Fastback bike designed with the familiar orange and white color scheme of the Texas favorite, Whataburger. The bike’s owner and designer, Danny Pechal, wanted to create the piece as an homage that felt purely Texan when competing around the country. Sporting an eye-catching neon orange, the small but intricate bike holds a scavenger hunt’s worth of Whataburger iconography, from the “24-Hours” sign posted on the front wheel, to the signature “W” logo emblazoned on the sides, wheels, and handlebars of the bike.

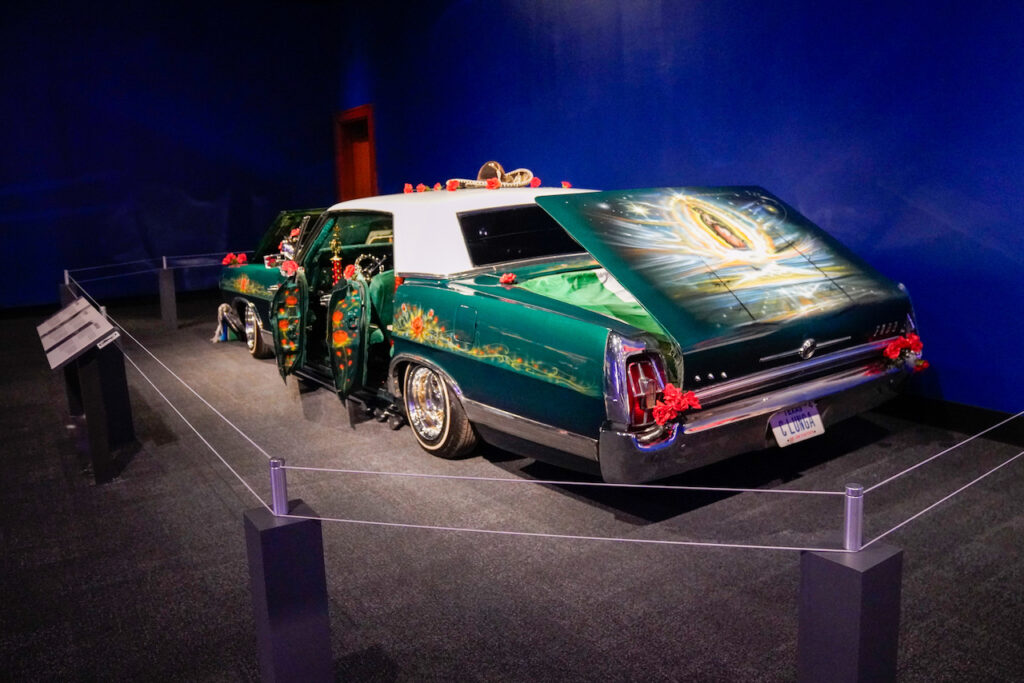

Another element of cultural representation comes through in Austin lowrider John Colunga’s 1967 Ford LTD, which displays a mixture of high-quality materials and refined technique to create two massive painted murals. Colunga used a polyurethane paint that is also used on airplanes, buses, and trains, creating murals that are not only detailed works of art, but also stand the test of time and weather. The murals, one a mélange of sky and color resembling the northern lights with a center image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a highly significant figure in Mexican Catholic culture, is accompanied by vines of roses that encompass the frame of the car. With a green body, white roof, and red painted details, the car and its colors represent a tribute to Mexico and its culture, cemented by the Mexican flag displayed proudly in the open trunk.

In gazing at the intricate creations of the lowrider designers, it’s important to also recognize the small details that come together to form these pieces of art. The exhibit displays the parts of what makes a custom lowrider special in both up-close models you can touch and an interactive digital game that gives the viewer a deeper glimpse into how much work goes into creating a fully customized lowrider car. Parts of the display include a chain-link steering wheel, switches for a hydraulic system, an engraved chrome plaque, and samples of the crushed velvet and leather upholstery that is commonly found in lowriders.

From the full-size cars exhibited in the museum to the small but vitally important details of engraved chrome and fabric, every aspect of creating a lowrider is displayed for visitors to enjoy. Even more impressive than the cars themselves are the stories, of communities coming together for the less fortunate, of families finding a collective bond through multiple generations, and of individuals finding their passions and holding pride in their unique works of art. Nowhere else will one see such strong community ties, a rich cultural history, and absolutely dazzling cars all in one place. This particular collection tells the story of lowriding beautifully, and is not one to be missed.

The exhibition, which ran at the museum from May 11, 2024, to September 2, 2024, is sadly no longer on display but it remains a significant achievement.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.