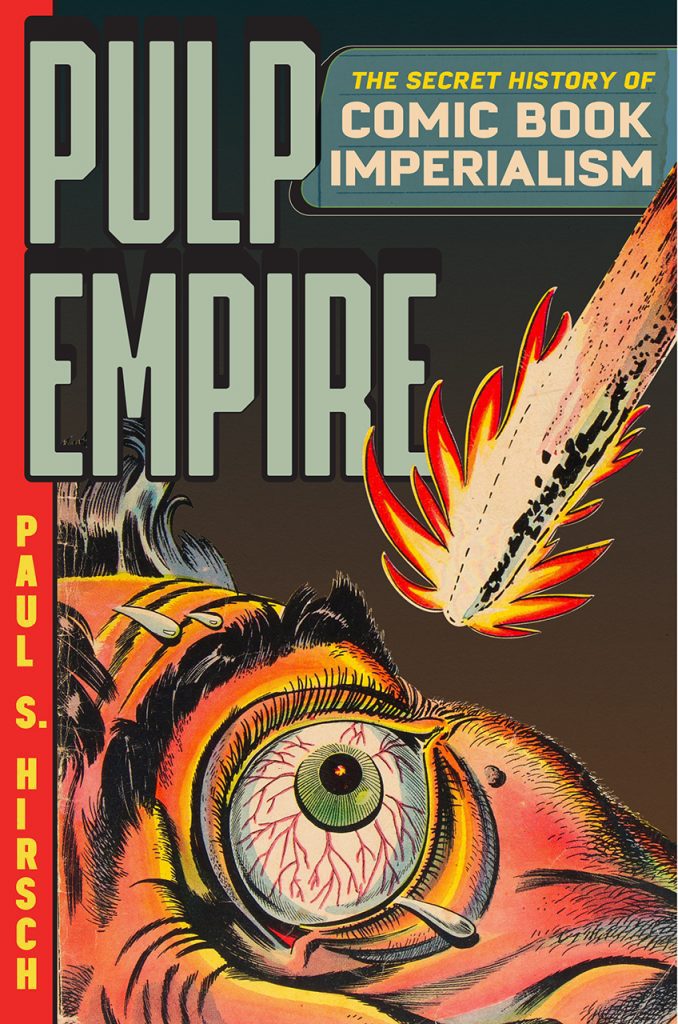

Over the last decade, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has grown into the most profitable media franchise in history. As of January 2022, the MCU accounted for four of the top ten-grossing films of all time. The expansive collection of films ranging from Iron Man (2008) to Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021) has captured the imagination of new generations of viewers and taken the genre to new heights of commercial and critical success. In Pulp Empire: The Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism, Paul Hirsch explores the origins of these superheroes who have experienced such a profound renaissance in recent years. Hirsch examines comic books as instruments of American empire and unpacks the complicated relationship between government and publishers that have shaped these comic books’ imagery and messages over their eighty-year history.

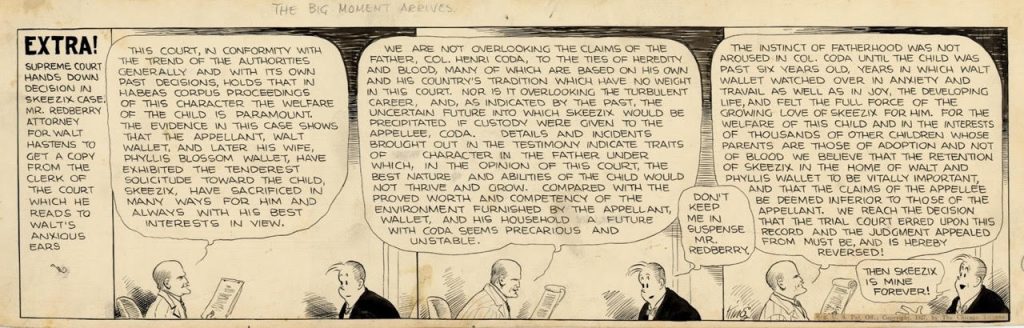

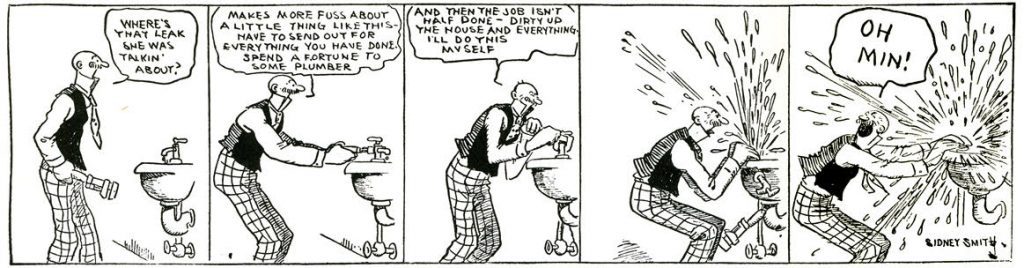

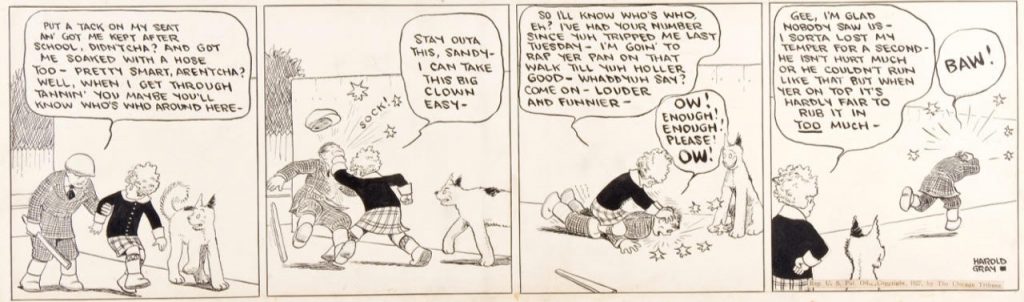

Hirsh’s book marks an impressive effort to elucidate the political, cultural, and diplomatic legacies of an artifact that has been regarded by many as “trash.” Such attitudes have meant that cartoons’ history has “been obscured through shame, malice, and benign indifference.” Yet, Hirsch has turned up treasures through his tenacious research and the full-page, full-color reprints splendidly illustrate his analysis throughout.

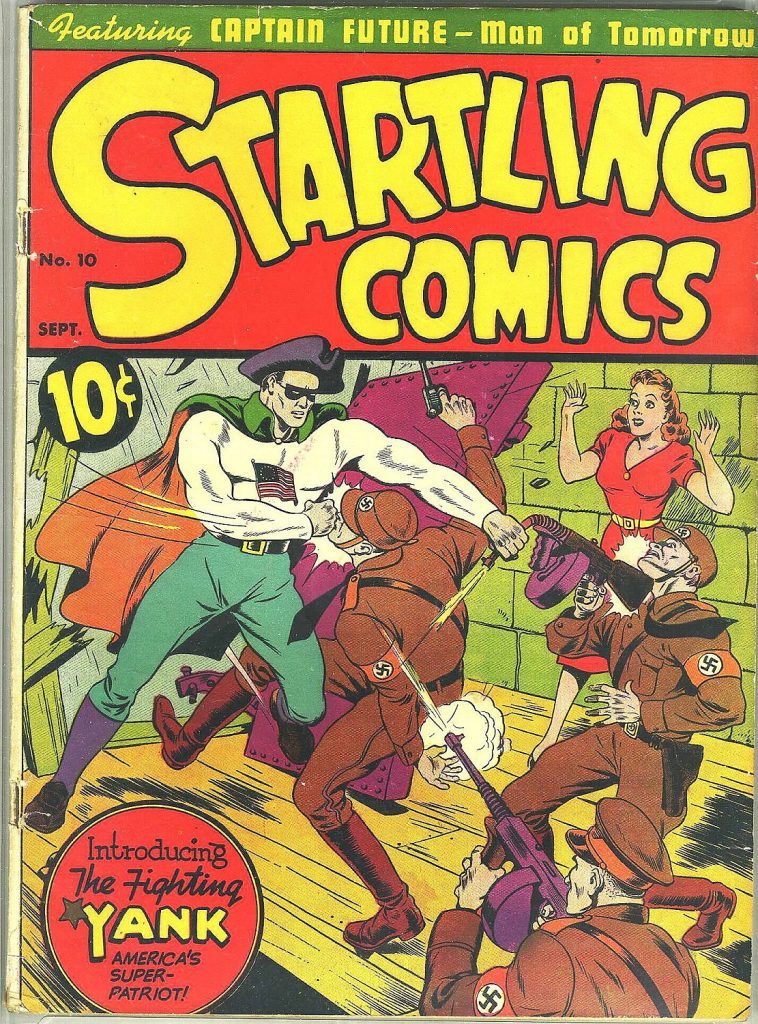

Pulp Empire traces the dynamic relationship between the industry and state and federal governments, a connection that influenced comic books’ development throughout the twentieth century. Hirsch characterizes the emergence of comic books in the 1930s as products that exploited the creative energies of marginalized men and women. Writers and artists were stingily compensated for their work, while publishers began profiting handsomely as the pamphlet’s popularity rose. American entry into World War II led the industry in a new direction as the US government sought to use comic books as propaganda to generate support for the war effort and promote racial stereotypes about the nation’s adversaries. The government largely stopped regulating the medium following the war and, during subsequent decades, the industry began to depict darker stories as American society lived under the pall of nuclear warfare. Pages were soon filled with gruesome images of crime, violence, and the destructive effects of atomic explosions.

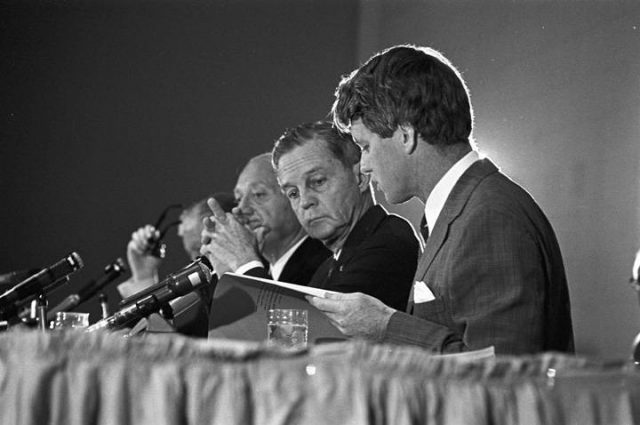

Such seedy scenes and pervasive racist attitudes in comic books invited criticism on several fronts. Hirsch profiles anti-comic campaigners who decried these pamphlets as corrupting influences on American youth that contributed to rises in crime and juvenile delinquency. Others took a different tack and warned that stories effused with racial enmity eroded American credibility as a beacon of hope and democracy abroad during the intensifying ideological conflict of the Cold War. Hirsch shows how these efforts ultimately resulted in self-imposed censorship. New covert collaboration between the government and publishers crafted fresh characters and narratives to serve as propaganda designed to condemn communism and improve attitudes toward the United States. Several superheroes who have gained acclaim in recent films, such as Iron Man, Thor, and Spider-Man, were born from this public-private partnership and acted as implicit (or in some cases explicit) agents of US foreign policy.

Pulp Empire is filled with fascinating anecdotes and incisive analysis of the ephemera of the US empire. This book offers something for an array of audiences, from fervent comic book fans to historians of American foreign policy. Hirsch deftly deals with several dimensions of comics’ hidden history, from their perpetuation of racist and sexist tropes to their use as a unique tool of soft power popular abroad across class lines. Finally, Hirsch’s analysis of the debates over the atomic age played out in comic book pages proves both entertaining and enlightening. Pulp Empire effectively interrogates the intersection between politics and popular culture and profiles how superheroes have been deployed to serve American expansionist goals.

Jon Buchleiter is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies United States history with particular interest in US foreign policy of the Cold War. His current research examines the institutionalization of arms control and disarmament efforts and successive administrations approached and prioritized arms control initiatives. At UT, Jon is a Graduate Fellow with the Clements Center for National Security and Brumley Fellow with the Strauss Center for International Security and Law. Jon received his BA in Peace, War, and Defense and Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.