People celebrate the Obergefell vs Hodges decision in front of the Supreme Court in 2015 (Ted Eytan, via Flickr)

In June 2015, by a vote of 5 to 4, the Supreme Court of the United States resolved decades of debate by declaring marriage a fundamental right regardless of sexual orientation. The Obergefell v. Hodges decision changed the landscape of American marriage law, but what was this landscape in the first place? Two historians of marriage and sexuality in the United States have spent decades taking on that very question. Nancy Cott and George Chauncey have both participated in recent history as expert witnesses, amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief writers, and eminent scholars analyzing marriage and homosexuality. They show us how incorrect we often are when we think of these histories in the United States. These historians have made history a friend to the court as much as any lobbyist or interest group.

Nancy Cott’s Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation lays out centuries of marriage law in the United States. Far from the moral absolute marked by religious teachings that many might assume marriage was, it is a complicated and shifting concept in the history of the Western world. Cott points out that marriage has a national concern that secular governments legislate in order to create the best “civic units” out of the family. Society became concerned with civic character and then tried to improve these norms by engineering a certain type of family. The common practice of unofficial divorce and separation led to a formal legal process for divorces just as much as the legal definition led to formal divorces. We are accustomed to thinking of these everyday things as defined from above, yet our community practices often find their way into law as often as the other way around.

Nancy Cott’s Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation lays out centuries of marriage law in the United States. Far from the moral absolute marked by religious teachings that many might assume marriage was, it is a complicated and shifting concept in the history of the Western world. Cott points out that marriage has a national concern that secular governments legislate in order to create the best “civic units” out of the family. Society became concerned with civic character and then tried to improve these norms by engineering a certain type of family. The common practice of unofficial divorce and separation led to a formal legal process for divorces just as much as the legal definition led to formal divorces. We are accustomed to thinking of these everyday things as defined from above, yet our community practices often find their way into law as often as the other way around.

The history of marriage in the United States certainly does not have the kind of unchanging moral character that many opponents to marriage equality claim. “Traditional” families are constantly changing. Two centuries ago, the most important people in deciding a match may well have been the community in which the couple lived. Small rural towns had a deep interest and broad powers in marital arrangements. Cott’s book is full of such examples of unofficial activities that reflected community interests, not the interests of the individuals involved. Marriage today is much more of an individual choice based on one’s own expectations from life, even if still affected by an idea of “normalcy” and pressures to fit into a family, a faith, or some other kind of community. Ultimately, the majority of Americans are free to marry outside of their “tribe,” because whatever social costs that are associated are considerably lower. Similarly, marriage was limited to “consenting” and “free” individuals. This meant that slaves were barred from this institution while also condemned as immoral for engaging in extramarital intercourse; a key aspect of reconstruction was the construction of ex-slave marriage. If marriage is an ever-changing reality, why shouldn’t the court consider homosexuals simply another kind of marriage?

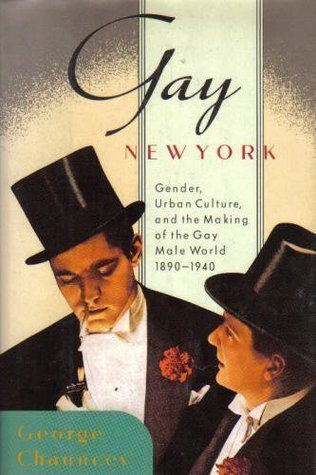

Marriage may be a concept in flux, but what about homosexuality? Today we identify people with their sexual orientation, but was that the case in the past? Many assume that throughout history, these communities were wholly underground — persecuted and kept hidden by families ashamed of their “perverse” siblings. But George Chauncey, along with a wide field of historians, have helped us to reconsider. Rather than being a gay or a lesbian, often individuals engaged in various kinds of sexual behaviors. In fact, Chauncey’s ground-breaking book, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940, outlined how urban men who participated in homosexual behaviors often considered themselves to be “normal,” that is, not defined by their same-sex intercourse, as long as they played the “active” role in intercourse. Those men engaging in the “passive” role in intercourse were seen from the outside as primarily a public nuisance on par with prostitution (which they often engaged in). The homosexual subculture of turn-of-the-century New York was visible and defined by specific kinds of sexual activities, not necessarily nature-born identities. In fact, the words we use today, such as “gay,” “lesbian,” and likely even “homosexual” would not have been known by the vast majority of people.

Marriage may be a concept in flux, but what about homosexuality? Today we identify people with their sexual orientation, but was that the case in the past? Many assume that throughout history, these communities were wholly underground — persecuted and kept hidden by families ashamed of their “perverse” siblings. But George Chauncey, along with a wide field of historians, have helped us to reconsider. Rather than being a gay or a lesbian, often individuals engaged in various kinds of sexual behaviors. In fact, Chauncey’s ground-breaking book, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940, outlined how urban men who participated in homosexual behaviors often considered themselves to be “normal,” that is, not defined by their same-sex intercourse, as long as they played the “active” role in intercourse. Those men engaging in the “passive” role in intercourse were seen from the outside as primarily a public nuisance on par with prostitution (which they often engaged in). The homosexual subculture of turn-of-the-century New York was visible and defined by specific kinds of sexual activities, not necessarily nature-born identities. In fact, the words we use today, such as “gay,” “lesbian,” and likely even “homosexual” would not have been known by the vast majority of people.

Twelve years before Obergefell, the Supreme Court laid the groundwork for this legal breakthrough. The June 2003 case, Lawrence v. Texas, challenged and then overturned what were commonly known as “sodomy laws” that declared sodomy illegal. Much of the debate surrounding these laws considered them to be expressions of long-standing morals; an accepted societal conclusion that homosexuality itself was illegal. However, Chauncey’s amicus curiae brief (with input from a number of historians) decimated this belief by pointing out that “sodomy” itself was a dubious term that had shifted throughout history. He pointed out for example that famed thirteenth-century theologian Thomas Aquinas considered every sexual act that was not direct penetrative vaginal sex to be sodomy. He also explained that the history of sexuality shows that these “morals” were recent inventions and historically changeable. His brief was specifically quoted by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote, whose opinion overturned decades of legal persecution.

Historians have much to teach, but not only to students. Society is improved by their scholarship, often because our collective memories are too short and our ability to see past our biases and preconceptions is often lacking.

Further Reading:

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (1995)

George, Chauncey, “What Gay Studies Taught the Courts: The Historians’ Amicus Brief in Lawrence v. Texas,” in GLQ 10, 3 (2004): 509-538.

Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation (2002)

You may also like:

Loving v. Virginia after 50 years

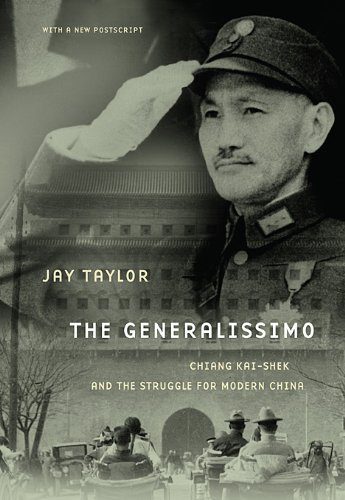

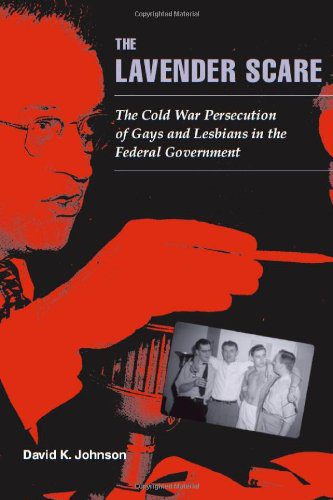

The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government reviewed by Joseph Parrott

Daina Ramey Berry on Slavery, Work, and Sexuality

In the wake of the Russian launch of

In the wake of the Russian launch of

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.