One of the pivotal issues that western historians of the USSR have debated since its collapse more than 25 years ago is its so-called “exceptionalism.” That is, to what extent should the history of the Soviet Union be considered as but one variation of the remarkable process of state modernization in the twentieth century, and to what extent might we posit a distinctively “Soviet modernity,” distinguished by its communist ideology, its party-based state, and its social and/or nationalist “neo-traditionalism.” In Crossing Borders, Michael David-Fox, a prolific scholar and one of the founding editors of the field-defining journal Kritika, brings together significantly revised versions of earlier publications with new material in a volume that takes aim at a comprehensive, holistic reframing of these much-debated questions. The very sensible central thrust is that we should and can transcend the binarisms that have developed — modernity vs. neo-traditionalism, exceptionalism vs. likeness. As he asserts in an ambitious introduction that sets a frame for the disparate chapters that follow, there is a way to “thread the needle” between the various interpretations that will allow scholars to arrive at richer understandings.

One of the pivotal issues that western historians of the USSR have debated since its collapse more than 25 years ago is its so-called “exceptionalism.” That is, to what extent should the history of the Soviet Union be considered as but one variation of the remarkable process of state modernization in the twentieth century, and to what extent might we posit a distinctively “Soviet modernity,” distinguished by its communist ideology, its party-based state, and its social and/or nationalist “neo-traditionalism.” In Crossing Borders, Michael David-Fox, a prolific scholar and one of the founding editors of the field-defining journal Kritika, brings together significantly revised versions of earlier publications with new material in a volume that takes aim at a comprehensive, holistic reframing of these much-debated questions. The very sensible central thrust is that we should and can transcend the binarisms that have developed — modernity vs. neo-traditionalism, exceptionalism vs. likeness. As he asserts in an ambitious introduction that sets a frame for the disparate chapters that follow, there is a way to “thread the needle” between the various interpretations that will allow scholars to arrive at richer understandings.

David-Fox determinedly asserts that the way out of historiographical and theoretical conundrums is not to abandon the terms of debate but rather to expand them. In particular, he suggests, that the way out of the impasse between proponents of Soviet modernity and neo-traditionalism is to utilize the concept of “multiple modernities,” which can resolve or at least contain some of the paradoxes. Of course, deconstructing binaries to arrive at a more sophisticated synthesis is not in itself a radically novel solution to historical debates, and the author strives to avoid oversimplifications of the numerous scholarly works that he examines. Threading the needle requires more than simply saying that the answer lies “in between,” and to his credit David-Fox claims to be aiming at that (or, more precisely, beginning the process of doing that) in compiling these essays and articles.

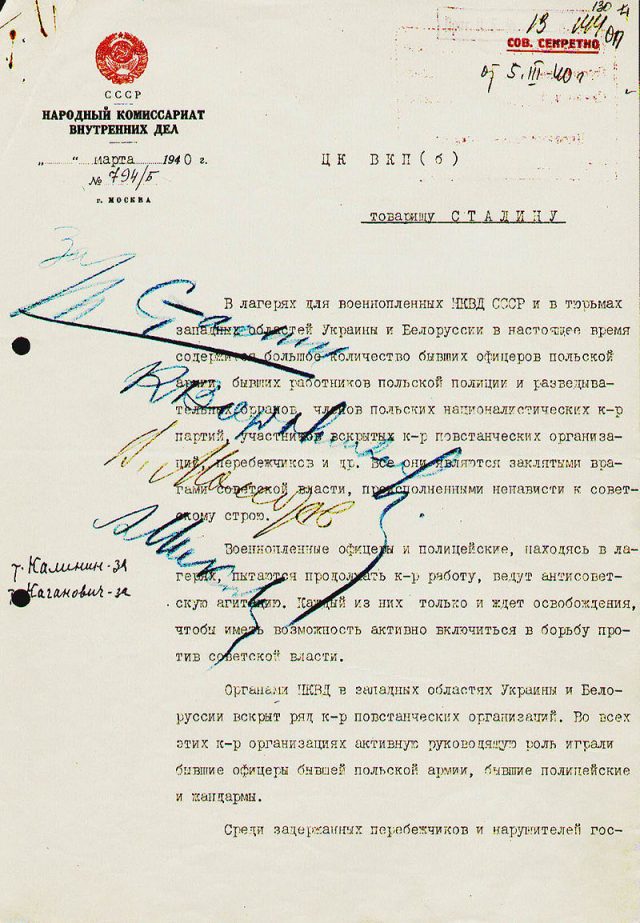

1924 pro-literacy poster by Alexander Rodchenko (via Wikipedia)

The chief features of this interpretation include a rigorous examination of what is denoted by modernity, and, in particular by an approach that is not merely comparative but aggressively transnational. Any evaluation of Soviet modernity must be done not only via comparison with multiple other modernities (and not just a stereotype of Western modernity), but also through an empirical examination of international interactions at the time. Focused primarily, but not exclusively, on the interwar period, David-Fox aims to demonstrate – in work building on his previous scholarship, in particular the recent Showcasing the Great Experiment – that patterns of influence were complex and multifaceted and cannot be reduced to a simple question of imitation. This volume aims not to resolve these complexities but rather to show empirically how intricate these interactions could be, and thus to suggest the need for still further examination by the field.

The book aims to “cross borders” not just between nations but also among various subdisciplines and approaches. In a new essay entitled “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” David-Fox examines definitions of “ideology,” asserting that for a concept so ubiquitous it has been curiously undertheorized by Soviet historians. This explication of six different modalities for studying ideology (as doctrine, as worldview, as historical concept, as discourse, as performance, as faith, and in the mirror of French revolutionary and Nazi historiography) offers a useful, concise, and comprehensive overview. Together with the examination of Soviet modernity and a significantly revised and expanded version of the author’s well-known “What is the Cultural Revolution?” the historiographical and theoretical chapters might offer, among other things, a precise introduction to the basic questions of Soviet history for graduate students and general readers.

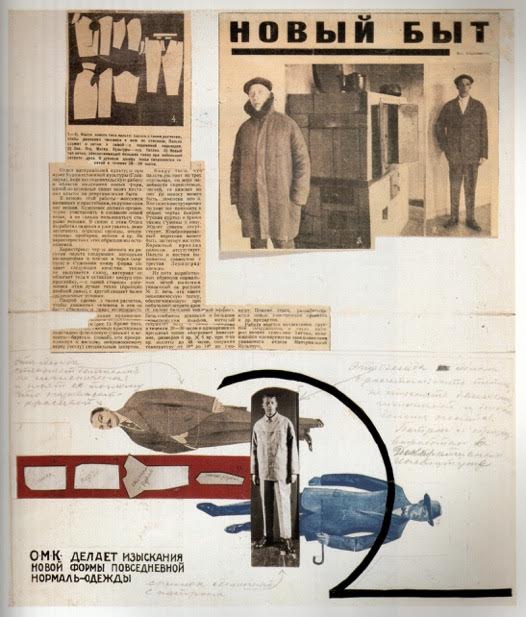

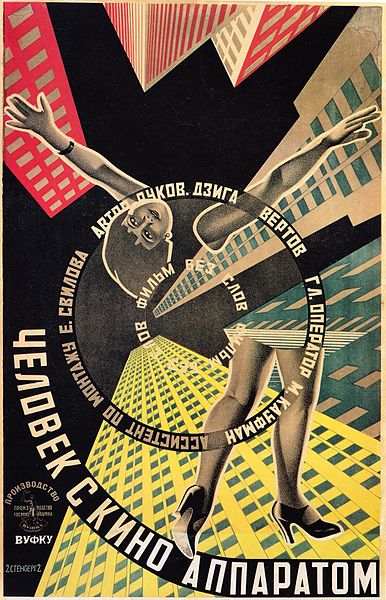

Poster of the experimental Soviet silent film “Man with a Movie Camera,” 1929 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The other major new inquiry in this volume is “The Intelligentsia, the Masses, and the West,” which provides a sort of précis of the author’s own original interpretation of what he calls “intelligentsia-statist modernity.” Impressively integrating the work of a diverse array of scholars, David-Fox posits that Russian/Soviet modernity was marked by “the way long-standing traditions of state-sponsored transformation were wedded to Westernized elites’ attempts to overcome Russian backwardness, and they all revolved around enlightenment from above and a search for alternatives to the market.” At the center of this conception is the well-known impulse of the Russian intelligentsia, the Kulturträger tradition, to disseminate “culture” to the masses. Here and in the revised version of his piece on the Communist Academy and the Academy of Sciences included later in the volume, David-Fox studiously avoids reducing the complexities and paradoxes of the Soviet integration of long-standing intelligentsia traditions. At the same time, in a book that strives to analyze and deconstruct major interpretative categories (modernity, ideology, etc.), it might be argued that this essay reifies a notion of “the intelligentsia” that is not sufficiently complicated. From at least the turn of the century, intelligentsia conceptions had been debated and contested, so that the original, more integral understanding had already been broken down. While there were undoubted strong étatist and tutelary propensities among the Russian/Soviet intellectual classes, there were also contradictory tendencies, including anti-intelligentsia sentiment and debates over fundamental concepts of social and intellectual life.

But it is clear that both this essay and the rest of the volume’s impressively erudite analysis represent far from the author’s last word on these matters. One expects an even more comprehensive framework will be built on these thought-provoking foundations.

You may also like:

Rebecca Johnston discusses policing Soviet art in early Soviet Russia

Julia Mickenberg on American girls in red Russia

Jessica Werneke reviews Consuming Russia: Popular Culture, Sex, and Society since Gorbachev ed. Adele Marie Barker (1999)