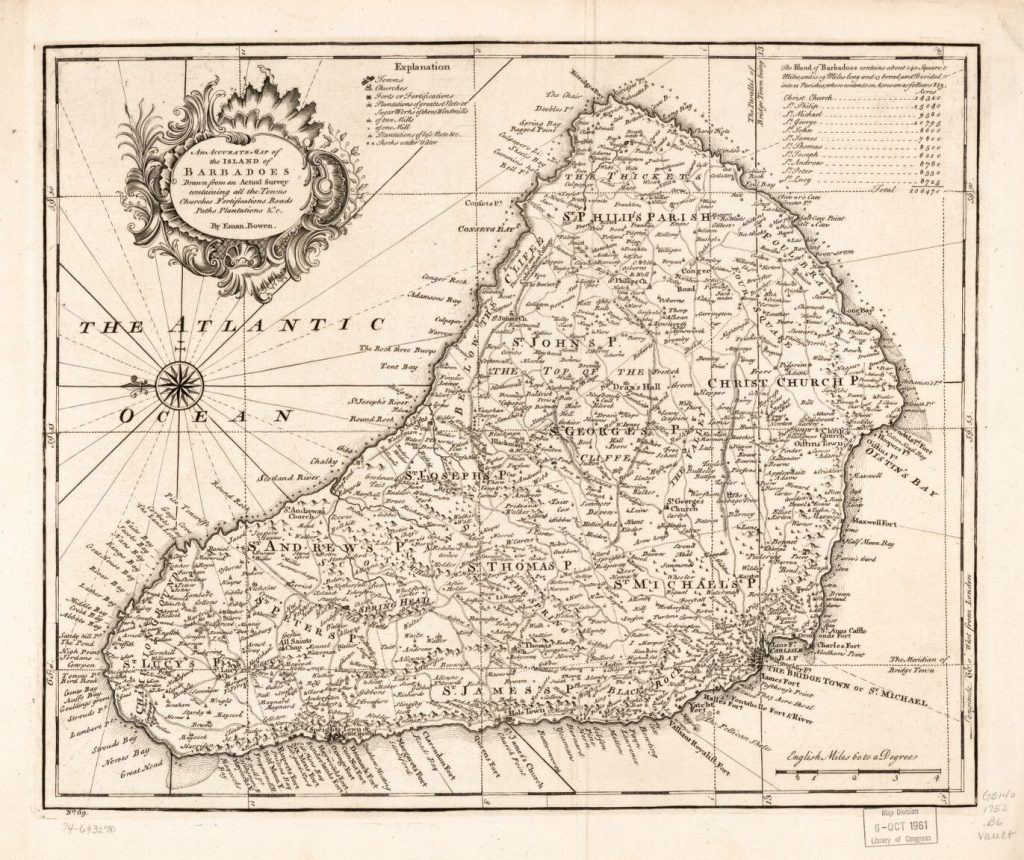

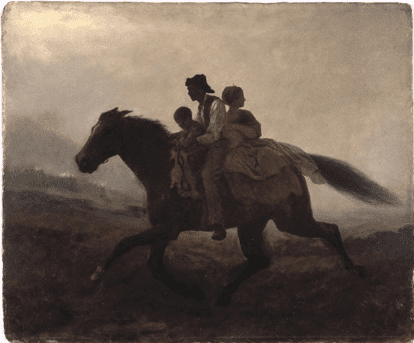

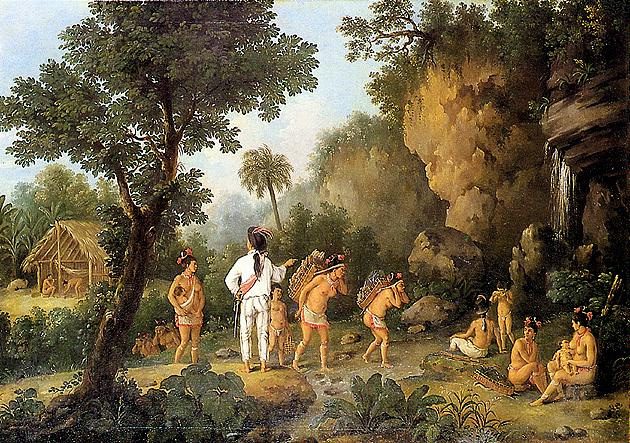

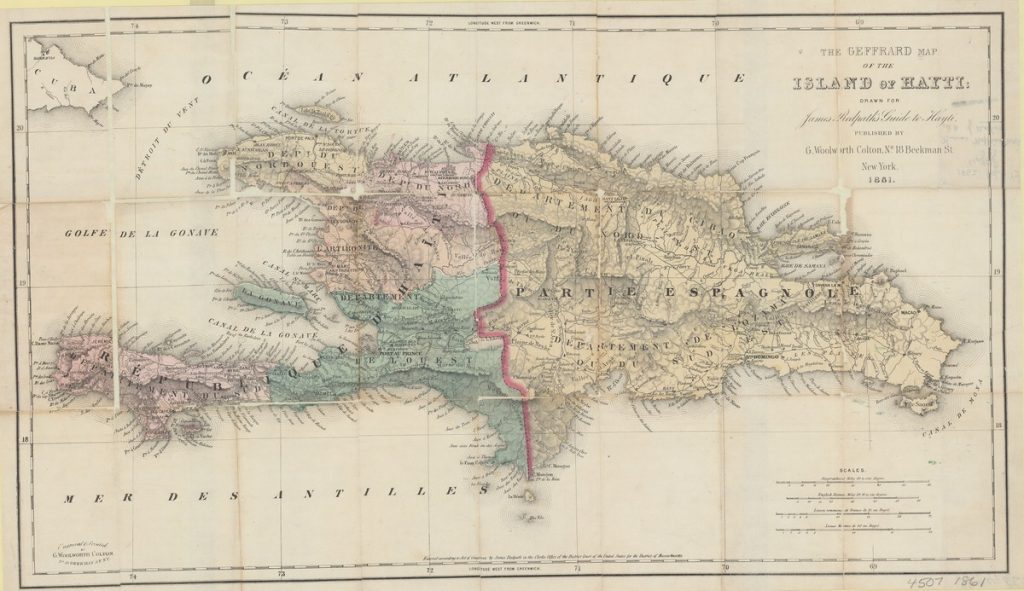

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Cuba was profoundly shaped by its proximity to and multi-layered relationship with Haiti, or Saint-Domingue as it was called before the 1803 Haitian Revolution. In the decades leading up to Saint-Domingue’s 1791 slave revolt, Cuban planters looked with envy on the booming sugar economy of their neighbor to the southeast and sought to emulate its success. After the revolution in Haiti, Cuba was able to take advantage of the implosion of Saint-Domingue’s sugar industry. Sugar production machinery and human expertise vanished from Saint-Domingue and reappeared in Cuba. Within twenty years of the first Haitian slave revolt, Cuba had surged ahead to become the largest sugar producer in the Caribbean. Necessary to that, of course, was human capital in the form of enslaved Africans or Afro-Caribbeans, some of whom may have been captives from Haiti. Between 1791 and 1821, slaves were imported into Cuba at a rate four times greater than in the previous thirty-year period. As a result, Cuban elites were forced to confront the growing probability, and then actual occurrence, of slave revolts.

Ferrer shapes her narrative around the “mirror,” or reversal, of historical processes: the collapse of one colony’s sugar economy and the rapid growth of another’s; the liberation gained by slaves on one island and the expansion of slavery and entrenchment of enslavement structures on the other; revolution and independence in one place and colonialist counterrevolution in the other; fears of re-enslavement on the part of former slaves and fears of revolt on the part of the elites. She argues that for Cuba, the Haitian Revolution in 1791 served as a temporal “hinge” between the “first and second slaveries.” The second slavery distinguished itself from the first in its larger scale and in its existence alongside a growing “specter” of abolitionist political movements and the reality of enslaved people successfully claiming and obtaining their own freedom.

The first half of Freedom’s Mirror takes the reader up to Haitian independence and victory over Napoleon’s forces in 1804. These chapters trace the evolution of Cuba’s “sugar revolution,” Cuban attempts to deter the import of negros franceses – Saint-Domingue slaves who might foment rebellion — and a short-lived alliance between the Spanish army based in the city of Santo Domingo (including soldiers from Cuba) and the Haitian rebels. The second half of the book showcases the conflicts resulting from the rise of coffee plantations in lands occupied by communities of runaway slaves, the 1808 turmoil in Cuba caused by Napoleon’s installation of his brother on the Spanish throne, featuring discussions of independence and slavery abolition, and the 1812 Aponte Rebellion.

Freedom’s Mirror, however, is not just a story about the causal relationship between the Haitian Revolution and Cuba’s transformation, and Ferrer does not confine her investigation to economic or political factors. What interests Ferrer are the “quotidian links – material and symbolic – between the radical antislavery movement that emerged in Saint-Domingue at the same time that slavery was expanding in colonial Cuba” (11). In particular, she tracks the circulation of knowledge, rumor, conversation, religious symbolism, anxieties and hopes that mapped onto infrastructures of commerce, slave-trading, government activity, and military action.

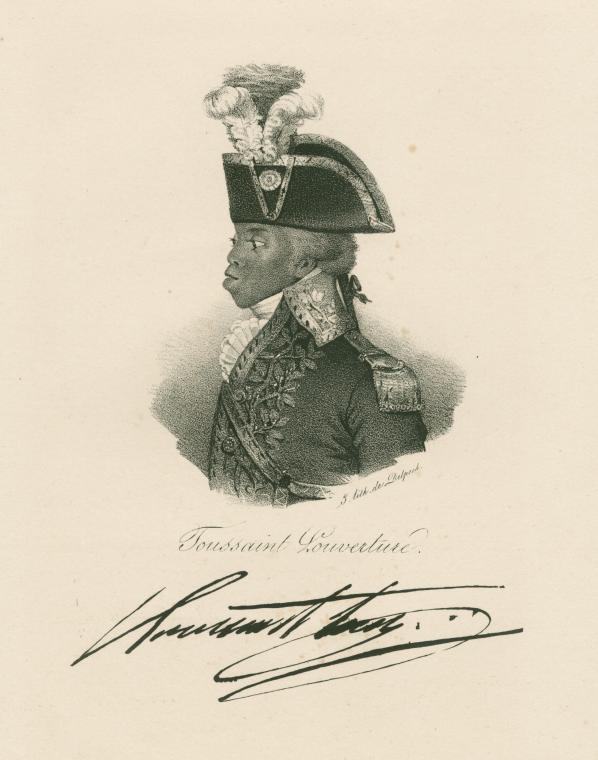

In 1801, for example, Toussaint Louverture’s forces occupied Santo Domingo and issued public proclamations. These were carried by ship crews and disseminated in Cuba, as were first-hand accounts of Spanish refugees from that occupation who had fled to Cuba. This, according to Ferrer, is the mechanism by which Cubans came to know of the events of the rebellion and the “spectacular ascent” of Toussaint Louverture (153). Eleven years later, images of the coronation of the Haitian King Christophe appeared in the prison holding suspects from Aponte’s revolutionary movement in Cuba. In the tradition of Lynn Hunt’s treatment of the “invention” of human rights, Ferrer uses her sources—city council minutes, port registers, trading licenses, letters, confessions of revolutionaries on the eve of their executions, and printed images of Haitian leaders—to document that this circulation of information and rumor transformed the interior experiences and decision-making of historical actors and ordinary people in both Cuba and Haiti.

Freedom’s Mirror situates Cuba in a regional history, primarily the interactions between Cuba and Haiti. Ferrer is fundamentally attuned to the circulation of knowledge, symbolism, and ideas. In bringing those into the light, she shows us that economic, political, and military realities never cease to shape, and be shaped by, subjective perceptions and individual actions.

You might also like:

Cuba’s Revolutionary World

Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Che Guevara’s Last Interview

Black is Beautiful – And Profitable

Making History: Takkara Brunson

Other Articles by Isabelle Headrick:

Madeleine’s Children: Family, Freedom, Secrets and Lies in France’s Indian Ocean Colonies, by Sue Peabody (2017)

Building a Jewish School in Iran