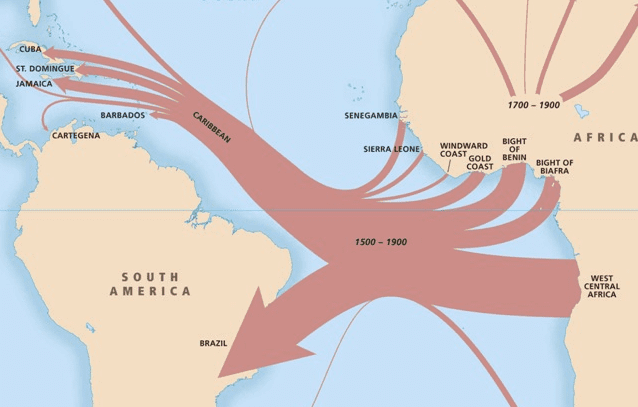

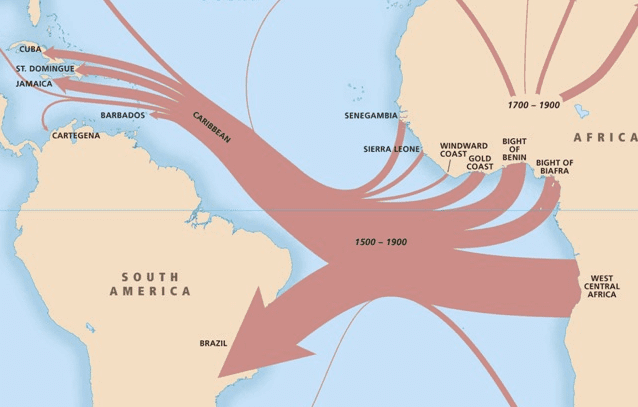

Roughly 12 million Africans were forcibly transported to Europe, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Americas between 1500 and 1900. As Emory’s Slave Trade Database shows, a huge proportion of Africans ended up in Colonial Latin America, shaping the emerging societies there and leaving a lasting legacy on race relations today.

Not Even Past has published numerous articles and book reviews on Slavery and Race in Colonial Latin America, covering a wide range of topics. What hierarchies conditioned the relations between Africans, Europeans, and native groups? How did these socio-racial systems work on the day-to-day of life in Colonial Latin America? And, how did racially discriminated groups resist? These are some of the key questions addressed in the articles below.

Spanish America:

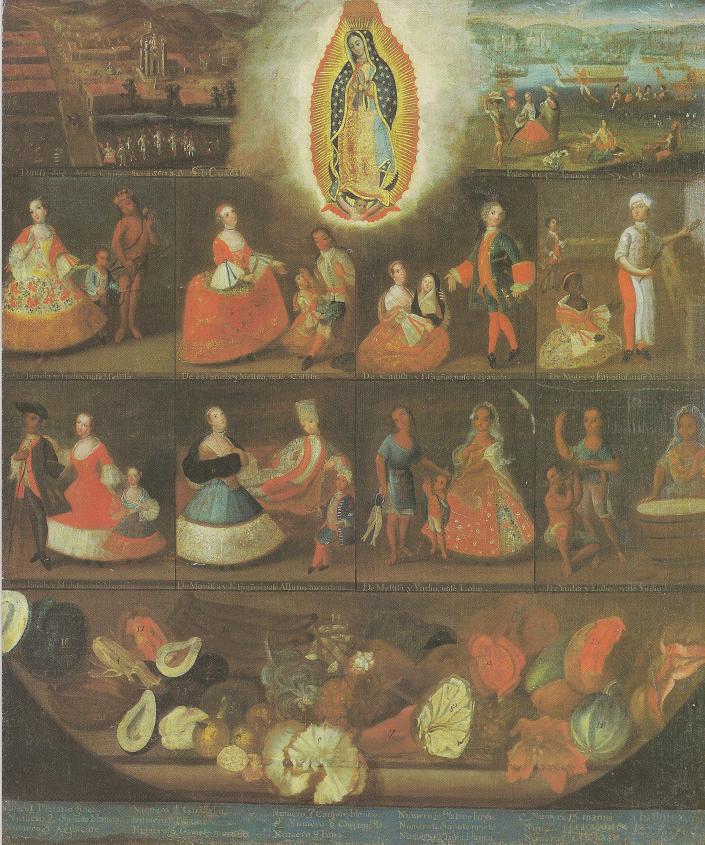

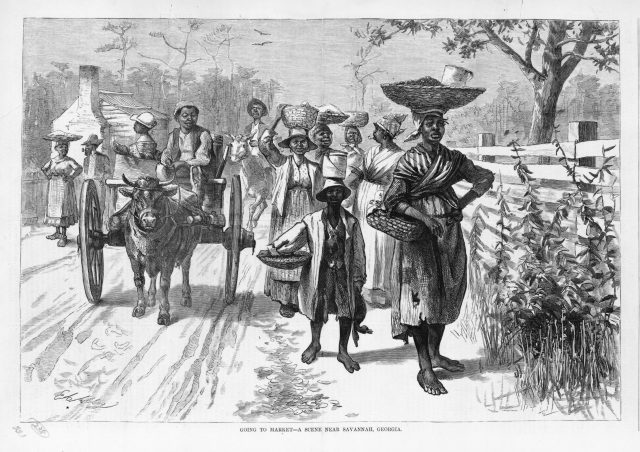

Susan Deans-Smith discusses the eighteenth-century Casta paintings, depicting different racial mixtures derived from the offspring of various unions between Spaniards, Indians, and Blacks.

The Casta paintings reveal an idealized hierarchical socio-racial system, but in practice some mixed race populations achieved social mobility by purchasing whiteness. Ann Twinam discusses.

Reviewing Joanne Rappaport’s Disappearing Mestizo, Adrian Masters highlights the gap between the rigid caste system and the reality of day-to-day life in Colonial Latin America and discusses his own work on the evolution of the Mestizo category.

Fluidity and malleability of racial identity was a defining feature of Latin American colonialism as Kristie Flannery discovers reading essays from Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

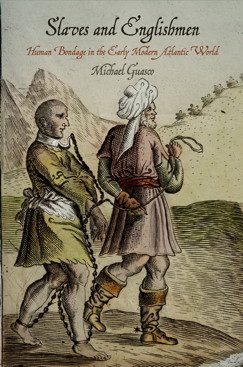

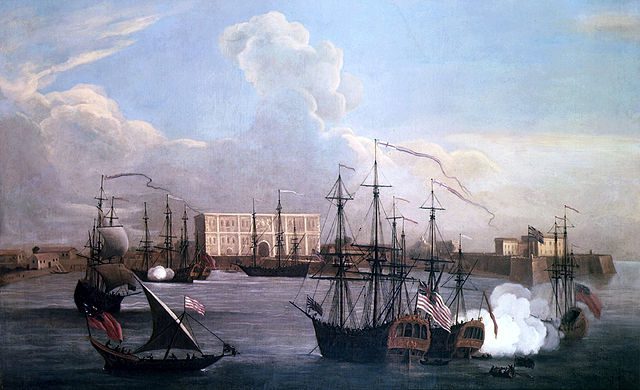

In the early modern Caribbean, individuals not only crossed socio-racial boundaries within the Spanish Empire but also shaped religious identities to move between Catholic Spanish and Protestant English worlds. Ernesto Mercado-Montero reviews Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block.

For further reading on the way identity worked in Colonial Latin America see Zachary Charmichael’s reviews of David Weber’s

Bárbaros: Spaniards and Their Savages in the Age of Enlightenment and Jane Mangan’s

Trading Roles: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Urban Economy in Colonial Potosí.

Brazil:

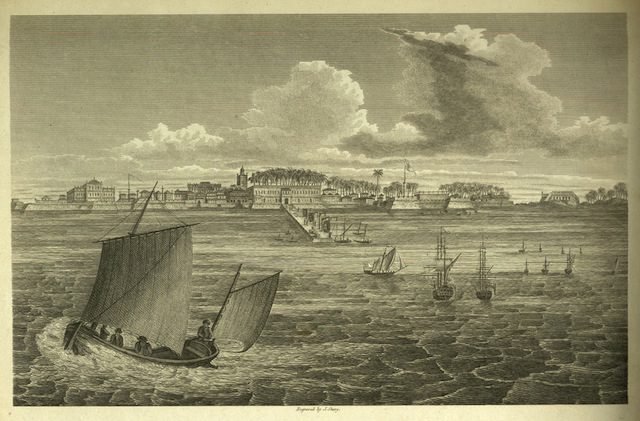

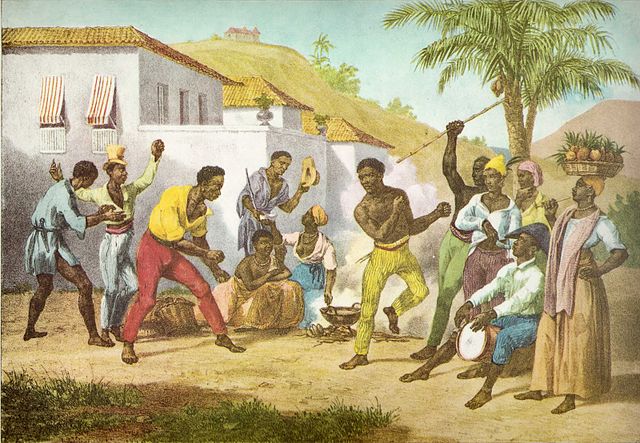

As the slave trade database shows colonial Brazil was one of the principal destinations for slaves transported from West Africa, creating an unique Luso-phone Atlantic world. In her review of studies by Mariana Candido and Rocquinaldo Ferriera, Samantha Rubino highlights the cultural exchange between Portuguese and Africans, altering the way historians conceptualize creolization and the formation of slave societies.

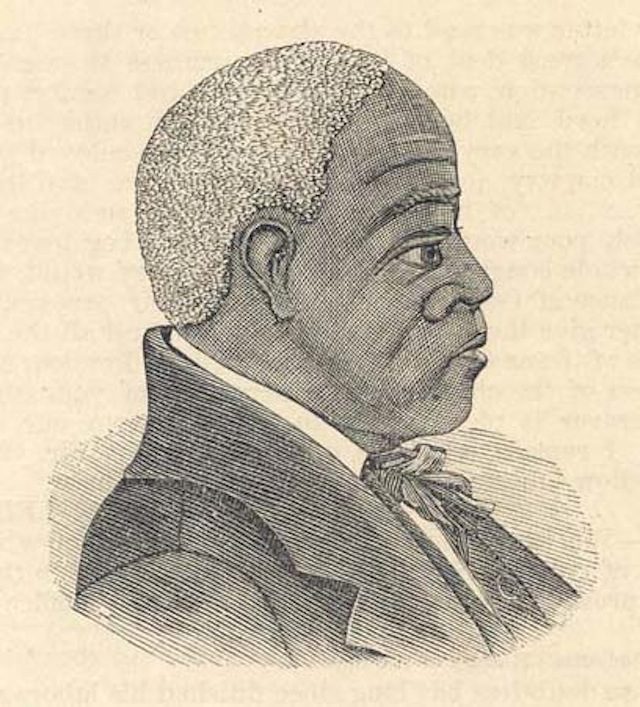

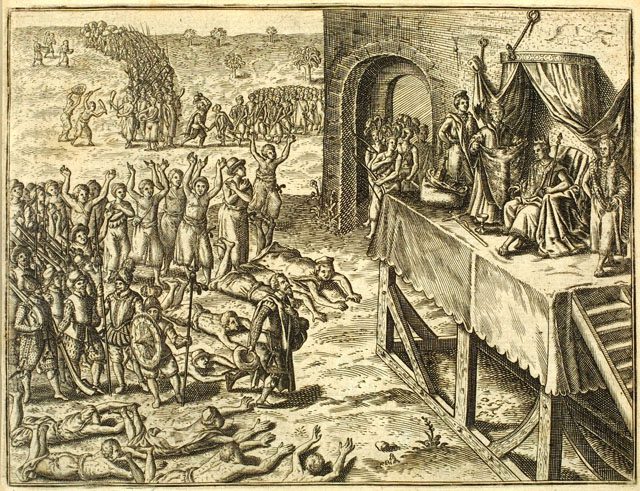

Portuguese officials meet with the Manikongo, who ruled the African Kongo Kingdom (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Michael Hatch discusses the story of Brazil most famous slave rebellion, the Muslim uprising of 1835 in Bahia, emphasizing the plurality of African ethnic identities in the development of Afro-Latino cultures rooted in the Atlantic slave trade.

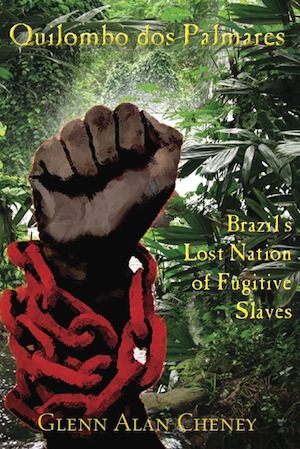

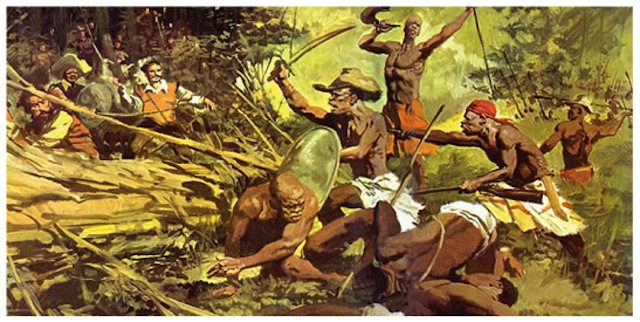

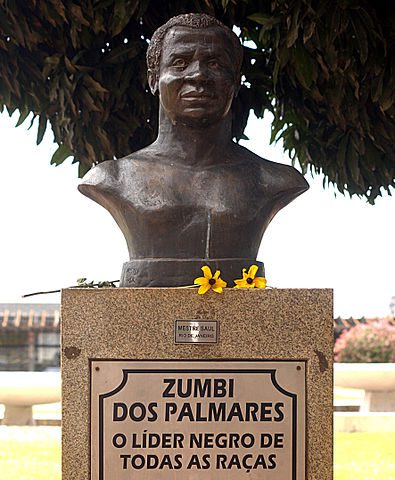

Also focused on Brazil’s North East, Edward Shore reviews Glenn Cheney’s Quilombo dos Palmares, unveiling the history of Brazil’s nation of fugitive slaves.

For more on casta paintings:

Magali M. Carrera, Imagining identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings (2003)

María Concepción García Saiz, Las castas mexicanas: un género pictórico americano (1989)

Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (2004)