Eduardo Castañeda

Nimitz High School

Senior Division

Individual Exhibit

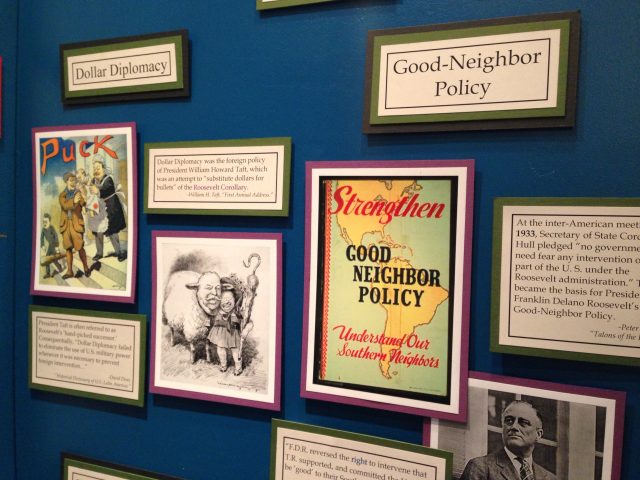

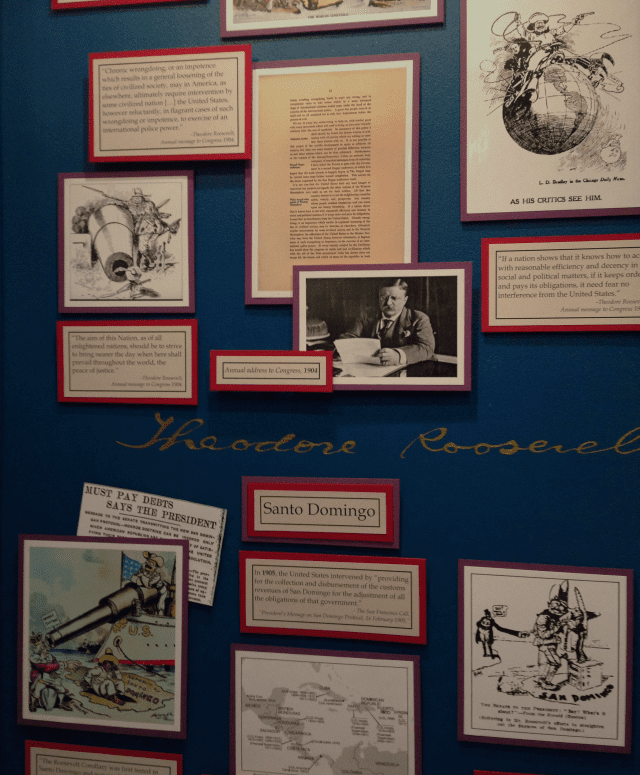

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt announced a new “Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823: that the United States would no longer simply protect Latin America from foreign powers, but actively intervene in their domestic affairs. Over the coming decades, the American government became highly involved in Latin American politics, commerce and military matters. The Roosevelt Corollary has since been a deeply polarizing moment in world history. To some, it inaugurated an era of muscular and confident American foreign policy. To others, especially in Latin America, Roosevelt’s policy represented an act of imperialism designed to protect American military and commercial interests.

Eduardo Castañeda of Nimitz High School considered the heated debate surrounding the Roosevelt Corollary with an exhibit at Texas History Day, “Colossus of the North.” He talked about the experience of researching this controversial topic in his process paper:

Having been born in a Latin American country, I am interested in the foreign relations between the United States and Latin American countries. After researching several U.S.-Latin American topics, I discovered the “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, which explained the interactions between the U.S., and Latín American countries. The “Roosevelt Corollary” justified the right for U.S. intervention in Latin American countries, and the responsibility to become a police force for the entire Western Hemisphere.

The “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine fits this year’s theme, “Rights and Responsibilities in History.” For decades, the “Corollary” impacted the political, economic and social structure of the Western Hemisphere. This interpretation transformed the US. foreign policy from a preventative one, according to the Monroe Doctrine, to one that justified and encouraged U.S. intervention in Latin America. The “Corollary” promoted Stabilization of economies, military intervention and protection of US. Commercial interests. ln 1905, the U.S. took control of Dominican customs houses, and managed the tax Collections. ln many cases, military forces were sent to various locations in Latin America to subdue rebellions, assist revolutions that favored the US. and protect projects that the U.S. had an economic stake in. Professor Noel Maurer explained, “The Panama Canal would not have been built Without a U.S. sponsored revolution against Colombia, or payment for the construction and future use of the Canal.” The “Roosevelt Corollary” influenced other countries at the time, but it was the face of American foreign policy and transformed it throughout the 20th century. Roosevelt’s extension of the previously passive Monroe Doctrine changed how the United States interacted with the rest of the world. The U.S. had inherited the right to monitor the activities inside the Western Hemisphere, and undertaken the responsibility to enforce its Will upon those countries.

Last week’s Texas History Day projects:

The World War II internment you may not have learned about in AP US history

The painful story behind the Indian Removal Act

And one community’s famous response to segregation

![An image from "Flora Huayaquilensis," a visual collection of South America's plants as seen by Spanish botanist Juan José Tafalla during a 1785 expedition through Peru and Chile. ([Juan Tafalla], “Flora Huayaquilensis,” ourheritage.ac.nz | OUR Heritage - See more at: http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/7696#sthash.r8R9WHhx.dpuf)](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/87bbce75b1706f7ba39ef9bcbb7c9560.jpg)